The Omnivorous Reader

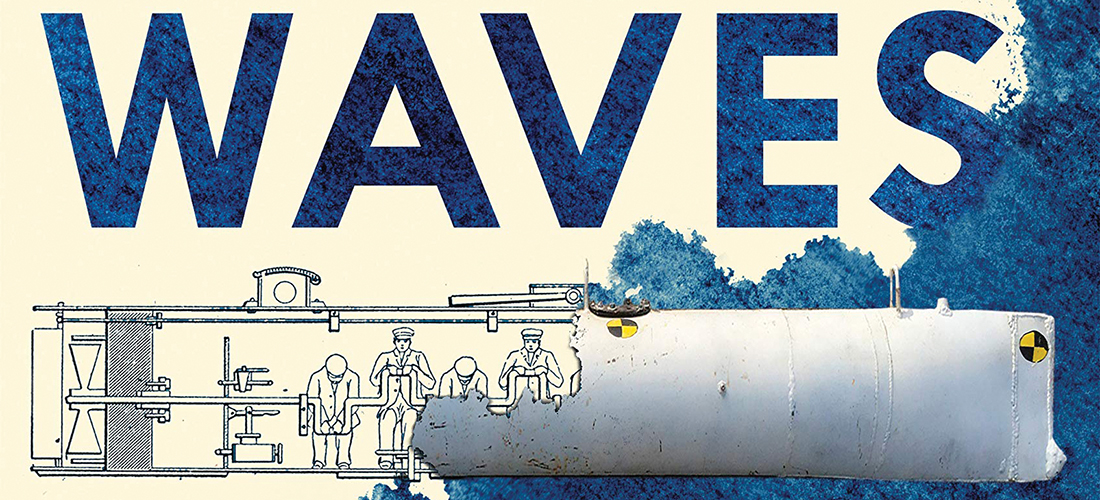

Mystery of the Hunley

What killed the Confederacy’s submariners?

By Stephen E. Smith

With an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 Civil War—related titles published in the last 155 years, you might wonder if there’s anything left to write about. But science and technology have offered new methods of verifying the previously unverifiable, no matter how esoteric or insignificant the subject might be.

An April entry into the Civil War marketplace is Rachel Lance’s In the Waves: My Quest to Solve the Mystery of a Civil War Submarine. This 315-page semi-technical analysis of a single black-powder detonation that changed naval warfare forever should be of interest to anyone living in the Carolinas, taking place, by and large, at Duke University, and concerning an artifact that has, in recent years, attracted thousands of tourists to the city of Charleston.

Lance is a biomedical engineer and blast-injury researcher at Duke. She spent several years as an engineer developing specialized underwater equipment for the Navy and was working toward her Ph.D. when she took on, at the insistence of her dissertation advisor, the mysterious demise of the H.L. Hunley’s crew.

Any Civil War enthusiast (let’s dispense with the pejorative term “buff”; many Civil War readers are serious historians) will be happy to tell you that the Hunley was an experimental submarine developed by the Confederacy in hopes that it would break the Union blockade, and that it might have succeeded except that it disappeared along with the USS Housatonic, the first warship sunk by a submersible craft, and remained cloaked in mystery until 1995, when it was located 4 miles offshore in 30 feet of water. The sub was raised from the bottom in 2000 and has since become Charleston’s most popular attraction.

For those unfamiliar with the details of the Hunley’s story, Lance supplies a history of early submersibles and details the little sub’s short life, including the circumstances surrounding the first two Hunley crews, who perished when mechanical problems arose during testing. Even H.L. Hunley, the sub’s inventor, died when he accidently depressed the bow planes when surfacing following a test dive. After each sinking, the sub was raised and put back into service, even when it required that the bloated bodies of the dead be dismembered to facilitate removal, a decidedly unpleasant task relegated to slave labor.

For many years, it was assumed the Hunley had survived its attack on the Housatonic — it was reported that the crew signaled success by flashing a blue light — but there was no satisfactory explanation as to why the boat did not return to fight another day. Survivors of the Housatonic testified to seeing the Hunley shortly after the explosion, but no further evidence as to the fate of the sub and its crew was offered at the time.

Lance’s study focuses on the crew’s cause of death. Archaeologists found all eight men slumped at their stations in the submarine. Seven men were seated at the propeller crank, and the remains of the boat’s captain, Lt. George Dixon, were discovered in the forward conning tower. None showed signs of skeletal trauma, and there was no indication that the crew had attempted to escape the sinking craft. A careful examination of the boat’s skin revealed that the explosion had not breached its hull.

Since Lance is a blast-injury expert, readers might assume that she was seeking confirmation that the crew was killed by the shock wave from detonation of the Hunley’s torpedo, and not from suffocation or drowning. In fact, Southern newspapers speculated shortly after the sub’s disappearance that such a wave had sunk the little boat, and knowledgeable observers at the time of the sub’s testing warned that the Hunley would likely fall victim to its own torpedo, which was suspended on the end of a spar extending from the bow of the boat.

Lance’s objective was to prove beyond all doubt that a blast wave killed the Hunley’s crew, and In the Waves is a narrative history of her quest to gather evidence to that effect and to procure, in the process, her Ph.D. To do this she constructed a miniature Hunley-like craft (the CSS Tiny), procured black powder of the sort available during the Civil War, constructed a miniature facsimile of the torpedo, and conducted extensive testing in an appropriate body of water. Instruments to measure the true force of the blast had to be obtained from the Navy and made to function correctly under circumstances that were anything but ideal.

The development of testing criteria consumes most of Lance’s book, at times growing a trifle tedious and dauntingly technical. Failed test follows failed test, subjecting the reader to the same level of frustration suffered by Lance and her team of researchers. But she wisely couches much of the technical information in understandable terms and refers more punctilious readers to the open-access journal PLOs One. “This is a descriptive version of the math and physics,” she writes in a footnote, “and was written to be understandable for the general reader. It does not, therefore, go into all the complex details necessary to justify and complete the scientific analysis.”

While working to replicate the explosive force of the Hunley’s torpedo, Lance reveals the intriguing story of George Washington Rains. Born in Craven County, North Carolina, Rains almost singlehandedly supplied the Confederacy with black powder and torpedo technology. Southern soldiers may have run short of food and clothing, but they were never without powder and shot, a fact that no doubt prolonged the slaughter and destruction occasioned by the war.

In the Waves’ entertainment value is mostly a matter of scientific revelation. As a narrative it is made less successful by the inclusion of unnecessary details regarding the author’s personal life, and the occasional irrelevant sidebar and annoying digression. Is it worth reading? Certainly. If you have an abiding interest in Civil War history, you’ll no doubt find a place for In the Waves in your already overburdened bookshelves. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press awards.