Omnivorous Reader

Breaking the Code

The scientific revolution that changed the world

By Stephen E. Smith

What in the world just happened?

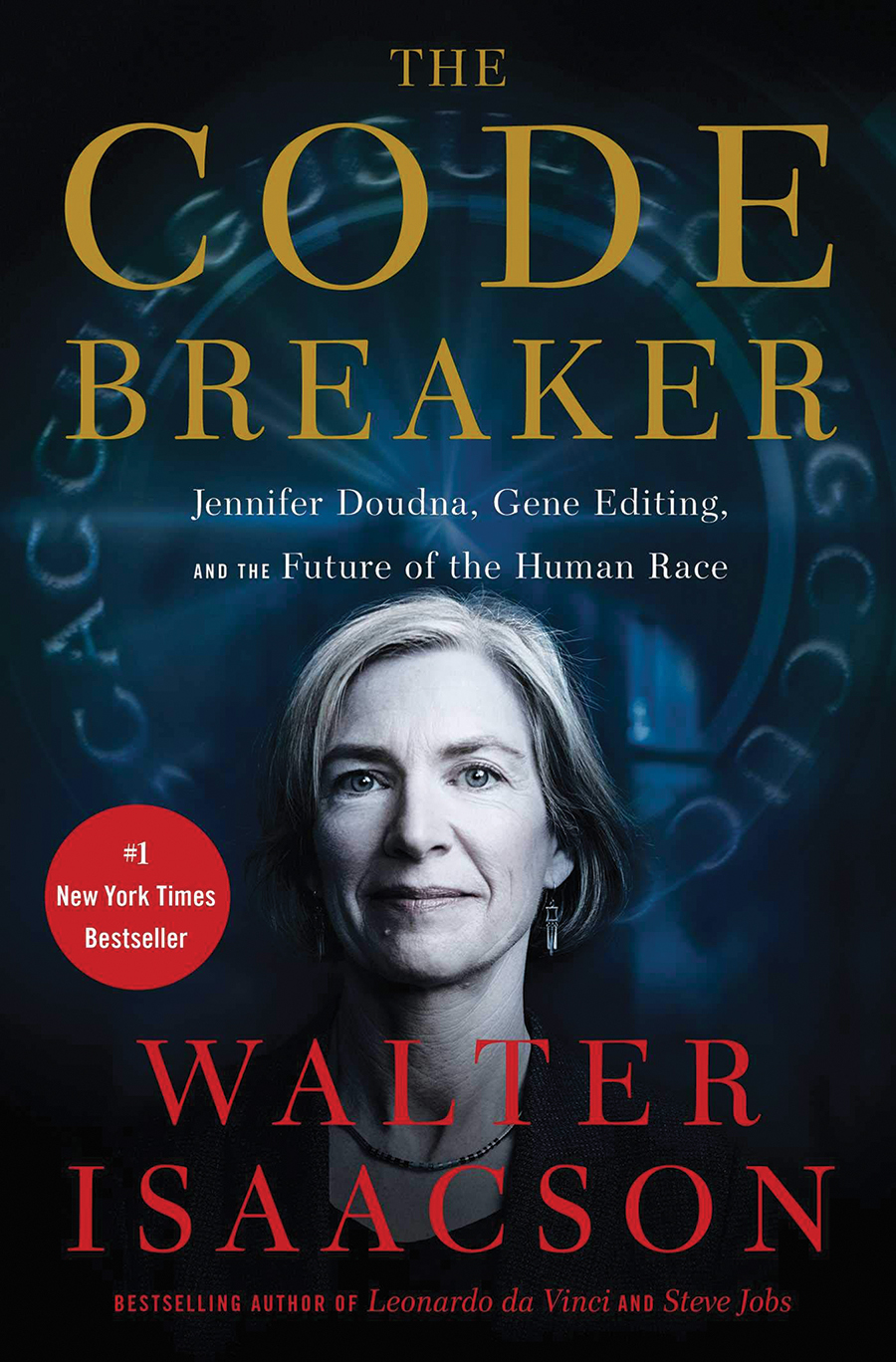

As the pandemic wanes, that’s the question many of us are asking. But a more immediate question needs answering: What are we going to do to prepare for the next pandemic? The answer, insofar as it’s possible to predict the future, is suggested in The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race, by Walter Isaacson, a quasi-biography that raises questions about nothing less imperative than our genetic destiny.

Isaacson, a history professor at Tulane University who has written biographies of Leonardo da Vinci, Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin and Albert Einstein, has a gift for explicating difficult scientific concepts. His biography of Jennifer Doudna, a 57-year-old professor in the Department of Chemistry and the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at the University of California, is the story of the development of CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) and the function of an enzyme (Cas9), a discovery that won Doudna and French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier the 2020 Nobel Prize.

A Doudna biography could not be timelier. Her CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology has launched a scientific revolution that allows us to defeat viruses, cure genetic diseases and certain cancers (TV advertisements are already touting such treatments), and, perhaps, have healthier babies. She has changed our world, moving us from the digital age into a bio-life sciences revolution that will affect our lives to a greater extent than computers have or will.

Doudna was in the sixth grade when she read James Watson’s The Double Helix, initially mistaking it for a detective novel. Watson’s groundbreaking research into the human genome was a mystery so intense that it set her on a career path as a university researcher who would eventually develop an easy-to-use device to edit DNA. She helped discover a use for Cas9, a protein found in Streptococcus bacteria, which attacks the DNA of viruses and prevents the virus from infecting healthy bacterium and cells. She was quick to recognize the possibilities for controlling viruses that invade human cells by using Cas9. “These CRISPR-associated (Cas) enzymes enable the system to cut and paste new memories of viruses that attack the bacteria,” Isaacson writes. “They also create short segments of RNA, known as CRISPR RNA (crRNA), that can guide a scissors-like enzyme to a dangerous virus and cut up its genetic material. Presto! That’s how the wily bacteria create an adaptive immune system!” CRISPR allows us to create vaccines to defeat the ever-evolving structure of coronaviruses. (A new vaccine under development at Duke University has the potential to protect us from a broad variety of coronavirus infections that move, now and in the future, from animals to humans.)

Once she’d figured out the components of the CRISPR-Cas9 assembly, she knew she could program it on her own, adding a different crRNA to cut any different DNA sequence she chose. “In the history of science, there are few real eureka moments, but this came pretty close. ‘It wasn’t just some gradual process where it slowly dawned on us,’ Doudna says. ‘It was an oh-my-God moment.’”

As with most life-altering breakthroughs, ethical questions abound. Should we edit genes to make our children less susceptible to diseases such as HIV and coronavirus? Would it be morally wrong if we didn’t? Isaacson devotes a sizable portion of the biography to asking and answering the tough questions that go to the heart of the CRISPR quandary: “And what about gene edits for other fixes and enhancements that might be possible in the next few decades?” he asks. “If they turn out to be safe, should governments prevent us from using them? The issue is one of the most profound we humans have ever faced. For the first time in the evolution of life on this planet, a species has developed the capacity to edit its own genetic makeup.”

In November 2018, He Jiankui, a Chinese biophysics researcher, produced the world’s first CRISPR-altered children. His goal was to make babies immune to the virus that causes HIV, but his colleagues in China and the West termed his accomplishment “abhorrent and premature.” He was found guilty of conducting illegal medical practices, fined a hefty sum and sentenced to three years in prison. But in the wake of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, the idea of editing our genes to make us immune to virus attacks seems a lot less shocking and a whole lot more enticing.

All of this is, of course, highly technical, but Isaacson explains much of what we need to know about CRISPR and its implications in terms that are apprehensible without dumbing down the science. Serious readers — and these days we all need to be serious readers — might peruse Doudna’s 2017 A Crack in Creation: Gene Editing and the Unthinkable Power to Control Evolution.

CRISPR will continue to change our lives — for the better, we can only hope. But science hackers are already employing CRISPR in unsupervised labs and neighborhood garages, and who knows what uses it will be put to. Will parents who have the financial resources enhance the health and IQ of their kids? Will we manufacture a class of humans whose superior strength and intellect allow them to dominate the majority? Given our history for employing new technologies, the possibilities are unsettling. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.