Food For Thought

The Tomato’s Last Hurrah

Summer’s carefree days have drawn to a close, but much of the bounty is still with us. Now’s the time to use up every bit of the tomato’s goodness

By Jane Lear

When I was a child, no one I knew cooked pasta (what we called noodles) with tomato sauce at home. In our part of the South, that sort of food was considered not just ethnic, but positively exotic, enjoyed as a special treat at the lone Italian restaurant in town. So although a college roommate introduced me to Ragú — we both thought it was pretty good — I didn’t have what you might call a relationship with tomato sauce until I moved to New York City in the late 1970s.

By sheer good fortune, I landed a job at Alfred A. Knopf, the legendary publishing house, and among the luminaries who graced the halls was Marcella Hazan, author of the instant classics The Classic Italian Cook Book and More Classic Italian Cooking. (Both books are combined in Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, published by Knopf almost 20 years later.)

Mrs. Hazan’s recipe for Tomato Sauce with Onion and Butter, from the first book, is at once devastatingly simple and life-changing. Aside from pasta and cheese, it lists just four ingredients: tomatoes (fresh or canned), one onion, five tablespoons of butter, and salt. That recipe, which is easily available online, has long been famous for being a gift to home cooks everywhere; periodically, it is rediscovered and wins a whole new fan base.

I made tomato sauce the Marcella way for years. Eventually, though, I branched out, impelled by curiosity and the fact that during the end of tomato season, God will strike me dead if I let a single soft-ripe heirloom go to waste. That’s how I found out that a sauce gets complexity and a good balance of acidity and fruity sweetness from a mixture of varieties, and those juicy heirlooms were more interesting to play with than the pulpier plum (Roma) types.

The basic sauce below is extremely versatile — it’s what my husband and I reach for when making pasta and pizza. It’s wonderful drizzled over flat fresh romano beans, a slab of meatloaf, or polenta. And it seems to taste even better when made with the last of the year’s tomatoes. I freeze as much of it as I can because the jar in the fridge will be gone in no time flat.

By the way, the key to a great tomato sauce is the right pot. You want something heavy-bottomed, to discourage scorching, and with a wide surface area, to aid evaporation. The less time the tomatoes spend reducing, the fresher and more immediate the flavor will be.

A few personal asides on tomato prep: Some people like to peel and seed tomatoes before making sauce; others feel it’s more efficient to toss everything into the pot, then pass the cooked sauce through a food mill to get rid of the gnarly bits.

I generally prefer doing the work on the front end, but unlike many folks, I don’t blanch the tomatoes in boiling water first. Instead, I plunk them in a bowl, pour a kettle of boiling water over them and make myself a cup of tea while I’m at it. By the time I’ve gotten a sieve organized over another bowl, the tomatoes can be eased out of the hot water one by one; with a little help from a paring knife, the skins slip right off.

When seeding tomatoes, first cut them in half crosswise — around the equator — exposing the seed pockets. Use a finger to loosen the seeds in each pocket, then empty the tomato halves over the sieve.

To save every drop of the juices, I don’t chop the tomatoes on a cutting board, but instead in my hand, over the sieve. My tool of choice is a Dexter Russell oyster knife; the straight-edged blade is dull yet can still get the job done, the rubber handle is grippy in a wet hand, and the curved, rounded tip is ideal for flicking errant seeds out of the way. The chopped tomatoes go in the bowl underneath, and once you’ve pressed hard on the solids in the sieve, you can toss them into the compost pail knowing they’ve given their all.

Late-Season Tomato Sauce

Makes about 1 1/2 quarts

I’ve never found my finished sauce to be overly acidic, so it never occurs to me to add any sugar, but I’m no purist: It all depends on the tomatoes. If your sauce tastes harsh, add a little brown sugar to taste. Lastly, inspiration here comes from Marcella Hazan, but also the late Giuliano Bugialli, who taught me that basil isn’t used in a tomato sauce for its own flavor, but to bring out the flavor of the tomatoes themselves.

1/4 cup extra virgin olive oil

1 large yellow onion, chopped

3 fat cloves of garlic, minced

Several sprigs of fresh thyme, marjoram

or winter savory, tied together with kitchen string

5 to 6 pounds soft-ripe tomatoes, peeled, seeded and roughly chopped, plus

their juices

Coarse salt

1 or 2 fresh basil sprigs

A little unsalted butter, if desired

1. Heat the oil in a large, wide, heavy-bottomed pot over moderately high heat until it’s hot. Add the onion and cook until it begins to soften, then add the garlic. Cook, stirring occasionally, until the onion and garlic are thoroughly softened (don’t let them brown).

2. Add the tied herb sprigs, the tomatoes and their juices, and a generous pinch or two of salt. Simmer the sauce, uncovered, stirring occasionally, until it thickens nicely, about 1 hour. Taste the sauce and adjust the seasoning. Remove the herb sprigs.

3. After the sauce is done, add the basil sprigs, simmer the sauce an additional 2 minutes, then remove the basil.

4. Stirring in a little butter at this point will round out the flavors in the sauce and give it finesse, but it’s by no means necessary. I like a fairly chunky sauce, but if you prefer something smoother, purée it in a blender. Let the sauce cool completely, uncovered, before refrigerating or freezing. OH

Jane Lear, formerly of Gourmet magazine

and Martha Stewart Living, is the editor of Feed Me, a quarterly magazine for Long Island food lovers.

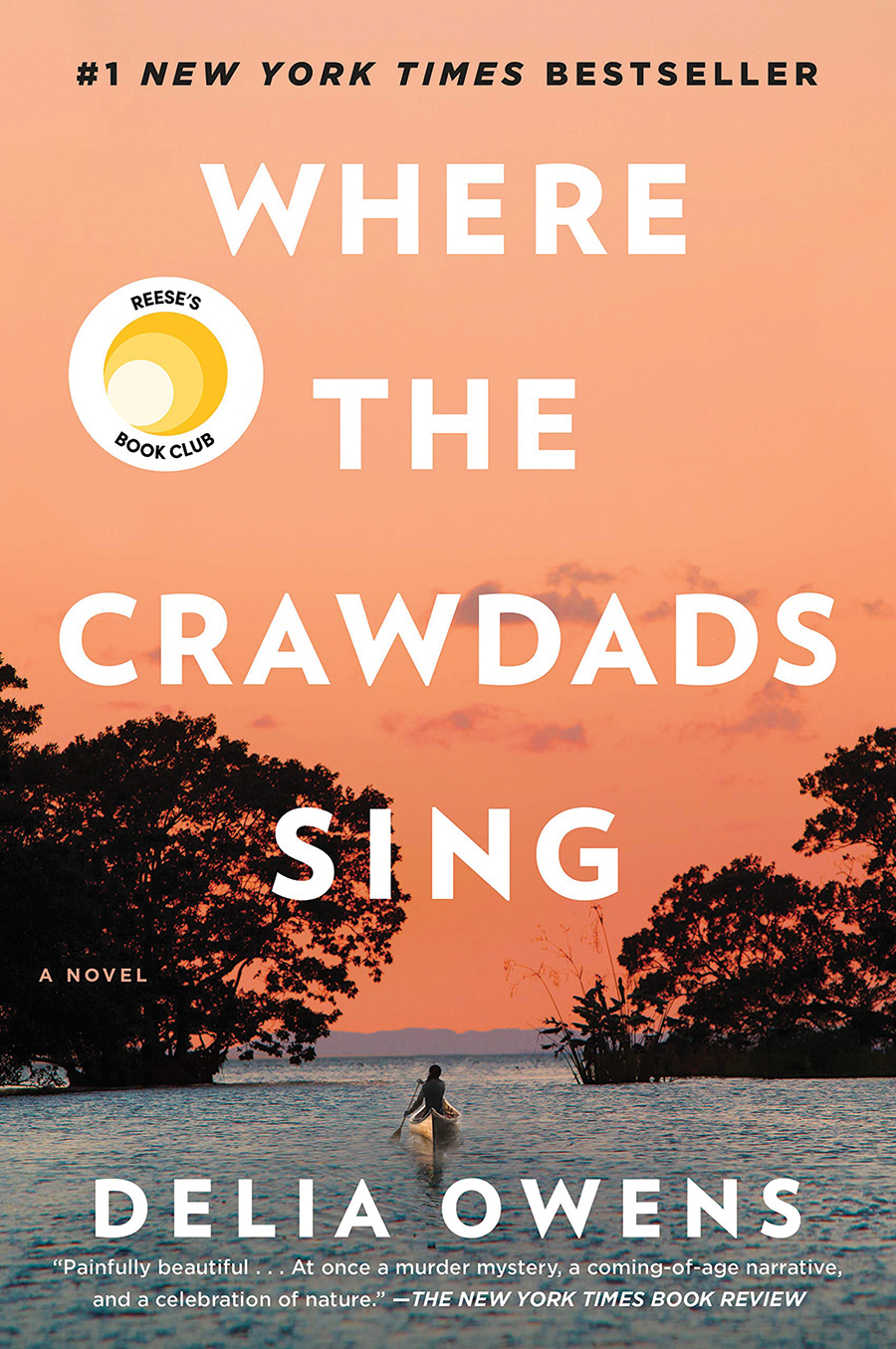

The Omnivorous Reader

Making of a Marsh Girl

Praise for a North Carolina tale

By D.G. Martin

For almost a year now, Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing has been at the top of The New York Times best-seller list, usually at No. 1.

For almost a year now, Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing has been at the top of The New York Times best-seller list, usually at No. 1.

North Carolina likes to be first at everything. Freedom. Flight. Basketball. Books. So, some of us have been bragging because Crawdads is set in North Carolina. Most of the action takes place in the fictional coastal town of Barkley Cove and the surrounding marshes, coves and ocean waters. There are side trips to real places such as Greenville and Asheville.

Others complain that the book’s geography is confusing, that the main character is unbelievable, that the framing of the African-American characters and their dialect is faulty, and that the storyline is broken and contrived.

However, the book’s many fans argue that Crawdads is genuine literary fiction in light of its strong and lovely descriptions of nature’s plants and creatures. They continue with praise about the book’s compelling murder mystery that has an unexpected ending and gives readers a superior entertainment experience. They applaud the coming-of-age story of the book’s central character, Catherine Clark, or “Kya.”

Kya was abandoned by her family as a child and lived alone in a shack in the marshes miles away from town. People in Barkley Cove think she is weird, keep their distance, and call her “the Marsh Girl.” She spent only one day in school and cannot read or write. However, because she is smart and diligent, she learns about the nature of the marshes.

When Kya meets Tate Walker, a young man from Barkley Cove, he senses her strengths and shares her love of plants and animals. He teaches her to read and write. They fall in love.

When Tate leaves Kya behind to study science at UNC Chapel Hill, she is devastated. Later, she rebounds to the seductive charms of Chase Andrews, a town football hero and big shot. Their secret affair is interrupted by Chase’s marriage to another woman, and Kya is again distraught.

Overcoming these disappointments, Kya leverages her reading, writing and self-taught artistic talents to record the natural world that surrounds her. When Tate, now a scientist, returns to her life, he persuades her to submit her work for publication. The book is a great success, and she writes and illustrates several more.

All this is background for the story that begins when Kya is grown and her former lover, Chase Andrews, is found dead at the bottom of an old fire tower. Kya is a suspect and is ultimately charged, arrested, put in prison and tried for Chase’s murder.

The evidence against her seems flimsy at first. But incriminating facts pile up, including her angry response to the married Chase’s attempts to seduce her. But she has a strong alibi. The author’s deftness in setting up this situation, and resolving it smoothly, has helped make it a best-seller.

A remaining mystery is how and why Owens, the author of two successful non-fiction books about the African natural world, came to write Crawdads.

After studying and writing about animal behavior, as she explained on UNC-TV’s North Carolina Bookwatch in September, “I wanted to write a novel about how much we know about how animal behavior is like ours. It can help us learn about ourselves. So I came up with this idea of writing this novel about a young girl who is forced to live outside of a social group. She’s abandoned. She’s never totally alone, but she has to spend a lot of time alone, and how does that affect her behavior? That is the question of my novel. Because Kya doesn’t have any girlfriends, she is missing something. She’s lonely, she’s isolated, and when people are forced to live in that sort of situation they behave differently.

“Kya was raised in the wild coastal marsh of North Carolina. She was born in the 1940s and lived through the 1950s and on, and so I chose the marsh because she is mostly abandoned by her family. She has to live most of the time by herself. I wanted the story to be believable, and the marsh is a temperate climate so she could live, she didn’t have to worry about snow or freezing, and she had a shack. She could survive because you can truly walk around and pick up mussels and oysters. I know it’s not easy, but you can learn to do it. It was possible for her to survive in that environment. That’s the reason I chose it.”

Owens, who spent much of her life in the wilds of Africa, far from any other human, explained, “There’s a lot of me in Kya: girl, love of nature, live in the wilderness for years, feeling like I don’t belong anywhere. There’s a lot of me in Kya, but there’s a lot of Kya in all of us.”

She says that being totally alone changes a person. “When I was isolated in Africa all those years, I wanted to have social groups. I wanted to have more contact with people. But when I came back, I found out it’s not so easy just to do it. And that’s what happens to someone who’s isolated like Kya. She longed to be with people, but every time she had an opportunity she was shy and didn’t feel socially confident.

“One of the points of the book is that you do not have to live in a marsh to be lonely. A lot of people in cities are lonely. A lot of people in small towns, even though they have friends, are lonely because we don’t have the strong, long-lived groups that we used to have. And when we get away from that, not only do we feel less confident and lonely, but we also behave differently toward others.”

How does Owens make a story out of an isolated young woman who lives in a shack in the marsh?

“I came with the theme first. I wanted to write a story of a young girl growing up alone and how isolation would affect her, but I knew I couldn’t just write that story. It had to have a love story, and it’s a very intense love story. It’s a very compelling, I hope, murder mystery. Of course when Kya reached adolescence, she reached the time that she wanted to be with other people, she wanted to be loved. So she started in her way reaching out, at least watching, and there is sort of a love triangle that follows that is very intense.”

Will there be a movie? Crawdads gained the attention of actress Reese Witherspoon. Fox 2000 has acquired film rights and plans for Witherspoon to be the producer.

We can hope that the movie will be shot in North Carolina. But here the book’s problem jumps up. The geography described in the book, with palmettos and deep marshes adjoining ocean coves, seems to fit South Carolina or Georgia coastal landscapes better than North Carolina’s coastlands.

Nevertheless, whatever the moviemakers decide, North Carolinians can bask in the reflected glory of a No. 1 best-seller that claims our state for its setting. OH

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch Sunday at 11 a.m. and Tuesday at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV. The program also airs on the North Carolina Channel Tuesday at 8 p.m. To View prior programs go to http://video.unctv.org/show/nc-bookwatch/episodes/

Papadaddy

Humor Me

These are difficult times. More reason than ever to ease up and have a good laugh

By Clyde Edgerton

In a small town stands a stucco building with two signs out front, one large, one small.

The large sign: Juanita’s Veterinary and Taxidermy Shop.

The small sign: Either Way You Get Your Cat Back.

Humor sometimes is forced to the backseat during this age of monster hurricanes, deadly drugs, poverty, wasteful wealth, anxiety, senseless car deaths, gun deaths, higher suicide rates, declining lifespans … WHOA! STOP!

Are the times really that bad? Or are the times being covered in such depth with penetrating media platforms, social and otherwise, that we just think times are worse than ever?

I mean, we at least got past the Middle Ages.

Answer: The times really are that bad . . . and there may be small, smooth ways to move, in your head, against bad times. To find a kind of comfort, a kind of distance from the noise.

Humor lightens the load. In some cases, humor close to home, maybe in the neighborhood.

A man who happens to be blind stands on the corner at Market and Third. His Seeing Eye dog is peeing on his leg. The man is trying to feed his dog a Fig Newton. A woman across the street sees what’s happening, checks for traffic, walks over and says, “Excuse me, sir, did you know your dog was peeing on your leg?”

“Yep,” says the man.

“Well,” says the woman, “why are you trying to feed your dog a Fig Newton?”

The man says, “When I find his head, I’m gonna kick his ass.”

A small funny story (except to the dog, perhaps).

A different kind of entertainment tends to come from other places, from big obscene movie stories, for example — stories with blazing killer weapons and blatant blasts of blood. These movies seem to compete with our big crazy times, and maybe that’s why fans flock to them. These movies seem to say, “The world is getting crazier and uglier and more violent, and thus citizens deserve crazier and uglier and more violent movies. We are keeping up with the times.”

But crazy times also create the need for us to find more little stories from our own neighborhoods and communities. Sit on your front porch for a while. Watch. Listen. Talk to a neighbor.

Go buy some honey, see what happens.

Recently, a friend said he’d take me to a home where I could buy some good honey. He was a regular visitor. He knocks on the door to a sun porch. Somebody says, “Come in.” Inside, an elderly woman (about my age) is sitting at a small table, putting together a giant jigsaw puzzle. Her husband is sitting on a couch across the room. I and the couple are introduced, we shake hands. My friend and I take seats, and I ask about the puzzle — something to talk about before I buy some honey.

“Oh, yeah,” says the woman, “I do a lot of puzzles. I’ve probably done a hundred this year.”

I look at her husband, sitting quietly on the couch, and ask him, “Do you do puzzles, too?”

“Oh, yeah,” he says, slowly. “If we didn’t have puzzles, we wouldn’t have nothing to do.”

That was not an answer I could make up or find in a joke book, but for me (as a writer) it was golden — a little local story I’ve been telling my friends and have now written down.

Put the news aside. Talk to a neighbor. Discover a joke, a little story. Fight the bad times that way. Dismiss the cellphone and computer and TV for hours at a time. Hang on to the humor. Put some peanut butter on a piece of toast, add a little honey, go sit on the porch. Watch, listen. Find a story. OH

Clyde Edgerton is the author of 10 novels, a memoir and most recently, Papadaddy’s Book for New Fathers. He is the Thomas S. Kenan III Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at UNCW.

October Poem

Butterfly Effect

Chaos Theory revisited

A flash of yellow

flits across my window

Then another

and another

Cloudless sulphur butterflies

winging their way

once again

to southern warmth.

Do they know

they are fleeing

for their lives?

Do they know

a single wing flutter

has the power

to create or destroy

a tornado far from

the wing.

Unknowing

unaware as their instincts

propel them on.

As I watch from my window

I wonder how each breath

I take or don’t take

how each word I say

or don’t say

affects someone

or something

somewhere in my world

or the next.

— Patricia Bergan Coe

Scuppernong Bookshelf

Besties!

Be the best-read with every literary genre’s cream of the crop for 2019

Compiled by Brian Lampkin

It’s good to be reminded each October that the best of America can still be a thrilling, intellectually stimulating, fact-filled engagement with our most intriguing, diverse and serious ideas. On October 1, Houghton-Mifflin again brings us its finely edited collection of “Best Of” books in all genres. They’re priced to move at $15.99, and each book contains about 20 essays that have been culled from thousands of entries. The editors themselves constitute a best of American letters: Jonathan Lethem, Anthony Doerr, Rebecca Solnit and Samin Nosrat, among many others. These books are the best way to catch up on what mattered in 2019.

The Best American Short Stories 2019, edited by Anthony Doerr. Pulitzer Prize–winning author Doerr (All the Light We Cannot See) brings his “stunning sense of physical detail and gorgeous metaphors” (San Francisco Chronicle) to selecting The Best American Short Stories 2019. Doerr and the series editor, Heidi Pitlor, culled from The New Yorker end of the literary world, but also from the small presses that give underground life to the mainstream.

The Best American Essays 2019, edited by Rebecca Solnit. Writer, historian, and activist Solnit is the author of twenty books on feminism, western and indigenous history, popular power, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and disaster, including the books Men Explain Things to Me and Hope in the Dark; a trilogy of atlases of American cities; The Faraway Nearby; A Paradise Built in Hell The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster; A Field Guide to Getting Lost; Wanderlust: A History of Walking; and River of Shadows, Edward Muybridge and the Technological Wild West (for which she received a Guggenheim, the National Book Critics Circle Award in criticism, and the Lannan Literary Award). A columnist at Harper’s and a regular contributor to the Guardian, she knows a thing or two about writing essays.

The Best American Mystery Stories 2019, edited by Jonathan Lethem. One of my favorite American novelists, Lethem’s most recent book, The Feral Detective, understands that the urge to disappear is strong — especially in times ruled by The Beast. But Lethem also knows there are consequences — especially as imagined utopian communities turn dark themselves. Can’t wait to see his choices in the Mystery genre.

The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2019, edited by Edan Lepucki. Over the past year, fifteen Bay Area high school students have gathered each week in the basement of an independent publishing house (826 National) to pore over online and print literary journals, magazines, books, plays and graphic novels. They read things they couldn’t shake and engaged in deep conversations about how good writing brings people together, no matter what else is happening around the world. With the help of New York Times best-selling author Edan Lepucki they have compiled The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2019.

The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2019, edited by John Joseph Adama and Carmen Maria Machado. The stories selected by guest editor Machado for this acclaimed annual anthology reflect her commitment to exploring the boundaries between literary and genre fiction, asking “what sort of pleasures does this story bring me” instead of “what category is this?” Among the many and varied pleasures of the collection are stories that share Machado’s love of formal experimentation . . . this brilliant and beautiful collection is a must-read for those looking to enjoy the fullest range of narrative pleasure. Machado was in Greensboro for the inaugural Greensboro Bound Literary Festival in 2018.

The Best American Travel Writing 2019, edited by Alexandra Fuller. Fuller is the author of Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and Scribbling the Cat. She was born in England and grew up in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia.

The Best American Sports Writing 2019, edited by Charles Pierce. Pierce is a sportswriter, political blogger, and author of four books, including Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything. He has written for a wide variety of publications, including The New York Times, Esquire, Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe, Sports Illustrated and ESPN’s Grantland.

The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2019, edited by Sy Montgomery. Montgomery’s The Soul of an Octopus is one of my favorite nature books. Montgomery selects the year’s top science and nature writing from writers who balance research with humanity, and, in the process, uncovers riveting stories of discovery across the disciplines.

The Best American Food Writing 2019, edited by Samin Nosrat. Nosrat, author of Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, is the hottest chef in the business. She has been called “a go-to resource for matching the correct techniques with the best ingredients” by The New York Times, and “the next Julia Child” by NPR’s All Things Considered.

Brian Lampkin is one of the proprietors of Scuppernong Books. OH

Life’s Funny

Keep on Truckin’

How to Pick-Up Artistic Inspiration Along the Way

By Maria Johnson

I first heard about the truck called Mazy Mae this time last year.

I was meandering the aisles of a pottery show when I was snared by the playful animal designs of Oak Ridge artist Leanne Pizio, who was minding the menagerie.

We started chatting, and soon Leanne, who looked positively girlish in her blonde bangs, flowered skirt and western boots, was telling me now she spray-painted her Chevy S-10 pick-up truck with a different whimsical design every year.

Her themes were never offensive, but sometimes she caught guff for her mobile expressions. Once, at a gas station in Statesville, a stranger scolded her for ruining a perfectly good truck.

I asked Leanne how she handled the service-station critic.

“I tried to be nice,” she said, smiling and shrugging.

Then she invited me to witness the next painting of Mazy Mae, which is how I found myself driving to Oak Ridge late one September afternoon as the dipping sun cast a glow on fields brush-stroked with grass gone to seed.

Leanne calls it a fairyland, the undulating property that she and her husband Will Pizio have called home for the last 10 years. The centerpiece is a 1950s split-log cabin chinked with cement and shored up by stone, ringed by boxwood hedges, low stone walls and five gigantic holly trees.

Enchanted indeed, and the perfect dwelling for two free spirits. As Will puttered around the yard, Leanne invited me inside the cabin, where I was greeted, all at once, by the smell of wood smoke that has smudged the upper lip of the fireplace and by three rescue dogs that hover around Leanne like a force field of gratitude.

The dogs settled into observation mode as Leanne poured iced tea into a couple of her animal-face mugs (I got a zebra!) and arranged a plate of butter cookies dimpled with homemade preserves.

Here’s a person who can’t help but take what life provides and create something new from it. In other words, a born artist.

She was that way, she says, even as a child growing up in Burlington.

“I was the fourth of four girls, so there aren’t a lot of pictures of me, but there’s one picture. I was about 3 or 4, and I’m on the patio in my painting smock, with my little easel and my paints.”

It was no surprise, then, that when she went to UNC Chapel Hill, intending to follow in the footsteps of her psychiatrist father, she was sharply diverted by an art class.

“I was hooked,” she says.

She graduated with a degree in psychology and minor in art, then tacked on a master of fine art degree from UNCG, where she grew to love painting and luvvvvv throwing and decorating pottery.

She honed a technique known as sgraffito (Italian for “scratching off”), in which the potter scrapes away a slip, or thin coating of colored clay, to reveal a contrasting color below.

The practice — which often yields dark-on-light designs — lends itself to Leanne’s drawing ability.

Many of her pieces reflect a love of animals, a fondness you’d expect from someone who has kept chickens and donkeys — and who has logged brief stints with dairy cows and goats.

No kidding; she once worked as a kidding apprentice — basically a baby goat sitter — at Goat Lady Dairy in Climax outside Greensboro.

“Farmers are the hardest working people in the world,” she says.

Over the years, in her own farm-to-table way, Leanne cobbled together a life funded by waitressing and selling her fanciful creations.

In 1997, she was living in Statesville and teaching art at a community college when she decided to paint Mazy Mae for the first time.

It was a difficult decision. She didn’t want to disrespect her parents; she’d asked them for a truck and they’d given her one as a present for graduating from Carolina. The ’91 Chevy was roomy enough for all of her art supplies. It was reliable. And it was white. Like a canvas.

Leanne mulled the idea for about a year before taking the plunge.

The first paint job was flying women with pretty dresses and large feet. “I’ve always loved feet,” Leanne explains. That’s the design that prompted the jab from the guy at the gas station.

Leanne warned her parents, by phone, about the truck’s new look; when they finally saw it, their reaction was accepting. Tepid, but accepting. Her sisters were tolerant, too.

“I think it might have been a little bit embarrassing for me to drive up to other homes in my crazy painted truck,” Leanne says. “But over years they got used to it and looked forward to seeing what was going on with it.”

In a way, Leanne’s experience with Mazy Mae symbolized what it’s like to be an artist; living between the call of your muse and the chance — nay, the certainty — that following the call will tick off somebody, somewhere, for some reason.

“You get to these places where you’re doing something that might be stepping on somebody’s toes, and, yes, you have to decide if you’re going to do that. I think all artists are in that position quite a bit,” Leanne says.

She’s not claiming to be a hero. There are times, she says, when she has rightly reined herself in.

But embellishing her own truck was low-stakes, so she continued covering it, at least once a year, with anything that inspired her: witches, ghosts, bunnies, bats, owls, American flags (after 9/11), llamas and sugar skulls to name a few.

She still raised eyebrows and drew snarks, but she also got a lot of smiles, honks and questions from people genuinely interested in Mazy Mae’s ever-changing wardrobe.

After her career took off, thanks largely to the encouragement of her husband and an agent who sold her works as interior decorating accessories, Leanne used the truck as a promotional tool.

When she created clay aliens for a gallery installment, she plastered the truck with funky extraterrestrials.

She also started parking the truck, festooned with balloons, on N.C. 150 as a flag for people who wondered which driveway led to her home, site of the annual Keep it Local Art Show.

Since its beginning in 1999, the show has grown from Leanne and one other artist, jewelry maker Lisa Skeen, to almost 25 local artists working in a variety of media.

Scheduled for October 26 this year, the event features live music, a food truck and a scavenger hunt of easy-to-find art pieces hidden on the grounds.

With tea drained and cookies crumbled, Leanne and I walked out to the yard where she had just started painting Mazy Mae with this year’s motif: crows flapping through a cornfield.

She held stencils cut from paper grocery bags against the truck’s skin, alligatored from more than 50 paint jobs over the years, and pointed cans of Krylon at the holes in the bags.

Psssst, psssst, psssst.

Orange oblongs = ears of corn.

Psssst, psssst, psssst.

Green stalks sprout to life underneath them.

Leanne hasn’t driven Mazy on the road in a couple of years; at nearly 30 years old , Mazy’s ticker is weak. If Will can start her, they’ll drive her to the top of the driveway to advertise this year’s show.

If she won’t crank, maybe they’ll tow her up there.

Or maybe they’ll leave her in the yard, next to the wood shed, and do something fun with her.

Remove her tires and windshield and make her cab a flower bed?

“I’ll never let go of her,” Leanne says, standing by the vehicle that’s carried her down the long and winding road known well by artists.

“We’ll figure out where she needs to be.” OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. She can be reached at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

For details on the Keep It Local Art Show, go to:

https://www.facebook.com/events/keep-it-local-art-and-pottery-show/keep-it-local/405657170156079/

Sylvan In The City

A Greensboro woman branches out by building an eco-friendly Airbnb, the area’s top wish-listed space

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Though it’s billed as a tree house, The Roost doesn’t qualify in the traditional sense.

Though it’s billed as a tree house, The Roost doesn’t qualify in the traditional sense.

It’s not tacked onto, leaning against or held aloft by a tree.

But the second-story apartment — Guilford County’s most wish-listed Airbnb lodging — is indisputably a house of the trees.

First, it’s bracketed on three sides by pines and maples, so guests get a squirrel’s-eye-view of the world.

Second, most of the building materials that Amanda Jane Albert and her crew used come from trees — hence the warm, resin-rich smell that greets you when you walk in.

Then there’s the gnarly tree branch that seems to sprout from one corner of the living room. The branch came from a dogwood that Amanda Jane and friends cut down when they started on the two-story building in 2015.

“We gave it a prominent place inside,” she says of the tree.

Last but not least, there’s a potted ficus happily photosynthesizing in the living area.

So the pad is about as tree-ish as a space can get without inviting woodpeckers and errant kites to take up residence.

The Roost does, however, host humans, lots of them, who book the one bed/one bath, $85-a-night property nearly every weekend and often during the week.

The Roost does, however, host humans, lots of them, who book the one bed/one bath, $85-a-night property nearly every weekend and often during the week.

Being Airbnb’s top wish-listed property in a county doesn’t necessarily mean the lodging receives the most bookings, a statistic Airbnb won’t release.

But it does mean Airbnb users have tagged the property as the place they’d most like to stay, should they come to the area, another measureof popularity.

The wanna-stay status squares with what guests have told Amanda Jane.

“People just really appreciate its uniqueness. They’re not surrounded by drywall and paint,” she says.

“They love being up in the trees. They feel like they’re in a retreat, this place for solitude and quiet. And that’s what I wanted it to be . . . a place for relaxation.”

In the beginning, Amanda Jane — a native of Louisiana who moved to North Carolina to build homes for Habitat for Humanity — wasn’t sure what the place would look like. Her then-boyfriend, also a builder, had constructed homes in colder climates.

In the beginning, Amanda Jane — a native of Louisiana who moved to North Carolina to build homes for Habitat for Humanity — wasn’t sure what the place would look like. Her then-boyfriend, also a builder, had constructed homes in colder climates.

Together, they wanted to experiment with making an Earth-friendly, energy efficient home suited to Greensboro’s weather, and they wanted to pay for it by listing the space via Airbnb, an online marketplace for hosts who have homes or rooms to rent, typically for short-term stays.

After casting around for a site, her boyfriend said, “Why don’t we build in your yard?”

Amanda Jane’s 1952 home — in a modest neighborhood near State Street in north central Greensboro — was within walking distance of a grocery store, coffee shop, restaurants and other amenities. The Revolution Mill complex will be an easy walk or bicycle trip away once a greenway is built from Elm Street to Yanceyville Street and beyond, as city planners propose. So Amanda Jane’s location was prime.

The building site was another matter.

Her backyard held a one-car garage and attached lean-to.

If she and her crew razed those outbuildings, they could build a one-story apartment on the spot, but the slope would require considerable foundation work.

That’s when Amanda Jane hit on the idea of lofting the structure on stilts. That way, leveling it wouldn’t be such a chore, insulating it from underneath would be easier, and space below the apartment could be used a workshop and storage room.

Amanda Jane drew the plans, literally, with a pencil. Tapping her Habitat experience and her interest in nature — she holds a degree in forestry management and ecology from Texas A&M University — she sketched at least 20 iterations before hitting on a compact, functional and aesthetically pleasing design.

Amanda Jane drew the plans, literally, with a pencil. Tapping her Habitat experience and her interest in nature — she holds a degree in forestry management and ecology from Texas A&M University — she sketched at least 20 iterations before hitting on a compact, functional and aesthetically pleasing design.

Next, she secured a loan from her mom and recruited friends to help with the project. She also spent hours tracking down building materials that were nontoxic, energy-efficient and environmentally-sustainable.

She ended up with a list of suppliers that included local and overseas businesses.

Her crew started construction in October 2015, and they finished in March 2016.

The result was a 426-square-foot apartment done in a style that could be described as “industrial-cottage” — lots of timber, metal and natural fibers woven together to create a warm and efficient space.

Forethought oozes from every feature.

The exterior is sheathed in cork, which is harvested sustainably, without felling the trees that produce it. The material is naturally insulating and insect resistant.

Inside the apartment, more natural material awaits. The floors are tongue-in-groove pine topped with a nontoxic, whey-based sealant.

The walls are shiplap pine, whitewashed with a plant-based pigment.

The ceilings are unfinished poplar.

The windows and doors, ordered from a German company, are highly efficient with triple panes and all-wood frames.

The space is heated and cooled by an electric split unit, and two HRVs, or heat recovery ventilators, that keep fresh air circulating.

“Because we made such an air-tight building, we needed a fresh-air supply,” says Amanda Jane.

Guests who crave more air can enjoy a covered deck that’s almost as wide as the enclosed space.

“That’s a trick when you have small house,” says Amanda Jane. “With a large outside space, you can double the living space.”

The television show He Shed She Shed, a production of the FYI Network, taped The Roost while it was under construction. The show’s staff donated the stainless steel cable railings that corral the deck. They also contributed some building materials and decorating accessories.

The apartment contains little freestanding furniture — the sofa, shelves, bed and nightstand are built in — but the interior is still visually interesting.

Standouts include the kitchen counter, which is made from old slate roof tiles, complete with nail holes.

Kitchen shelves are planks of salvaged barn wood resting on steel pipes that jut from the walls.

The base cabinets are made from formaldehyde-free plywood manufactured with natural glues and stained with a homemade concoction of vinegar, coffee grounds and tufts of steel wool that oxidized to darken the mixture.

In the living room, a hefty slab of live-edge timber rolls on an iron track to conceal a utility closet.

Amanda Jane created an accent wall by troweling lime plaster over laths, the old-fashioned way.

“Plastering is a lost art,” she says, noting that the lime also absorbs moisture in the air.

In the bathroom, three walls are cloaked with galvanized — and therefore rust-proof — corrugated metal salvaged from Peacehaven Farm in Whitsett.

Perhaps the sweetest touch of recycling is found next to the bed. Amanda Jane clipped a lace remnant to a rope that hangs, like a hammock, inside the window.

“The lace is from my great aunt. It was just lying around. I thought, ‘This is pretty.’ The rope was just lying around, too,” she says.

Amanda Jane has a talent for sniffing out reusable materials, whether in stores, on curbs or in construction-site dumpsters, says her friend Tay Halas.

“You’ll be driving down the road, and she’ll go, “Oh! Look at that!’” says Tay, who helped to frame The Roost.

Amanda Jane says her keen eye is fed by an open mind on the subject of what constitutes a building material.

For three years, she spent several weeks in Utah building straw-bale homes for low-income people. She pulls what she has learned in different climates and cultures into every project.

“I like the problem-solving and creativity of it, of saying, ‘I know I need something to function in this space. Now let’s look in different places to see what might work,’ “ she offers.

She launched her own business, Inhabit Living Solutions, about the time she finished The Roost; the apartment has been a good marketing tool for her skills.

So far, she has completed three projects: two garage adaptations for friends who created Airbnb rentals; and another garage upfit for a couple who moved, with their young child, into the smaller space in order to rent out the property’s main home, which they’d been living in.

Amanda Jane gets building permits for all of her projects like any other builder. She’s had no problem dealing with the city, she says, but she believes local government could do more to encourage affordable housing; reduce sprawl; help families accommodate loved ones; and create new income streams for people.

Updating codes on accessory dwelling units, or ADUs, in residential areas would be a good start, she says.

“I know there’s flexibility within Greensboro’s vision, but I don’t think anyone has advocated strongly for it.”

She points to cities like Portland, Oregon, where government encourages denser development to take advantage of existing city services.

“You gotta use what you got,” she says.

The total cost of The Roost was $65,000, slightly more than it would have been with conventional building methods, Amanda Jane says, but the payback has been a steady stream of Airbnb customers who’ve rated the property 4.99 out of five stars. The monthly income covers utilities for both the apartment and Amanda Jane’s home, as well as the loan repayment to her mother — all while stepping lightly on the planet.

“I do see it as a good investment,” Amanda Jane says. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. She can be reached at mailto:ohenrymaria@gmail.com”

O.Henry Ending

Leaving Home

Sorting through a lifetime of memories at a family estate sale is no easy task

By Lynne Brandon

“DO NOT ring the doorbell before 8 a.m,” read our sign on the front door. Not being “morning people,” my family recoiled at the thought of being dressed and ready to wheel-and-deal before breakfast.

This estate sale, as we preferred to call it, was born of necessity, not desire. After moving back to Surry County from Florida, my 83-year-old mother could no longer live in the house my sisters and I grew up in — a simple structure built by one of my uncles with wood floors that squeaked, a leaky basement when it rained, and 50 years of memories, love and good times.

Pickup trucks lined the country road as old timers in overalls, good ole boys, neighbors and “pickers” showed up ready to haggle over underpriced items — a house, full basement and three sheds’ worth.

Tables were spread with rock ’n’ roll 45s, quilts our grandmothers made on a quilting frame, Bassett Furniture (when it was still locally made), clothes, tools, football films on reels (from dad’s coaching days), farm equipment including our beloved 1950 Ford tractor and a lifetime of treasures.

Women gravitated to the house with glasses, dishes, books and kids’ toys. Men headed straight for the sheds so they could pick through tools and such.

Over the course of the day, we slowly realized that no price could be placed on the stories and memories that people shared. We met two older sisters driving an old red Ford truck, and former students who laughed as they related times of being disciplined by my father, known as Coach. There was Kenny, who told us that dad had talked him into working on his old truck instead of going to class — unheard of in this day and age. Kenny was happy to keep the Blue Goose running instead of sitting in a classroom. A cousin I had never met shared stories of my long-deceased uncle known far and wide as the best horse trainer in the region — a horse whisperer who could break horses no one else could tame.

Jackie Mears wiped tears from his eyes as he told me about how my uncle Wayne would plow a field of corn with the very same horse he would unhitch from the plow and then run in a race an hour later — and win. We have the horse ribbons to prove it. Jackie also told me how Uncle Wayne entered a race in Virginia dressed in jeans and riding Western amidst a field of other riders who wore jockey silks and rode English.

The most colorful visitor to our sale was the 40-something-year-old lady named Christie. She roared up in a beat-up Jeep, bristling with energy. “I got some tax money to spend,” she announced. She reminded me of Erin Brokovich — slim, busty, with bra-straps showing through her tank top, tattoos swirling at her ankles. She couldn’t have weighed much over 100 pounds soaking wet. In short fashion she pointed to four old and bulky pieces of furniture. Although all of our brawny helpers had left for the day, she was determined. “I don’t need no man to help me,” she said.

“Y’all remember that murder down the road about eight years ago?” she asked. “I shot and killed my ex-boyfriend,” she said matter-of-factly “He was drunk and tried to strangle me. It was self-defense.”

Though the tangible pieces of our lives were sold off one by one, that old house was more than a home; it was a weekend getaway, a refuge as I healed from divorce, and later a retreat away from the city to the wide open spaces and clean air of the country. Time spent in the basement talking to mom while she sewed on her Singer sewing machine and Dad sitting in front of the cast-iron potbellied stove, smoking a pipe in his overalls, are a flicker in my memory, like one of his old football reels.

Emptied of its contents, it is now waiting for new, young owners to fill it with the contents and memories of their own lives. This house was well-loved and it gave us lots of love in return. Now it stands ready to give again. OH

Lynne Brandon is a Greensboro-based journalist. She travels the South and wherever the road takes her in search of inspiring tales of people and destinations worth checking out.

Illustration by Harry Blair

Wandering Billy

Sharps and the Flat

Sheets music and other fine musical notes

By Billy Eye

“Every artist has a tendency to throw himself into the world. To see if he floats.” — Arthur Miller

Enjoyed an outstanding evening of music at the Double Oaks bed and breakfast recently, there to catch singer songwriter Matty Sheets who has a new album out. Built in 1909 at 204 North Mendenhall Street for Harden Thomas Martin, Double Oaks is one of the most beautiful homes in Greensboro, a Colonial Revival mansion with front columns reminiscent of the White House.

After Matty’s set, one of those freak thunderstorms plunged the neighborhood into darkness midway through Katharine Whalen’s set. But the former Squirrel Nut Zippers vocalist was unfazed: She merely switched out her electric for an acoustic guitar and kept right on singing. This was followed by Megan Jean, a self-described “hard-touring, foot-stompin’, guitar-beatin’, upright-lickin’, washboard- scratchin’, banjo-pickin’ madness with a voice like the devil herself.” She was a true revelation, reminding me of Bette Midler as she was emerging in the 1970s. Powerful vocals, emotionally rich songs with a rapier wit Jean described her unsuccessful struggles at getting a record deal between tunes. One of the grave injustices of modern times.

I caught up with Matty Sheets over black coffee and fried-green-tomato sandwiches at Freeman’s Grub & Pub, where I asked about his new recording, Anxiety: The Lay Dog Sessions. Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis three years ago, Matty recalls how once, “I hated playing shows because I hated people looking at me and seeing that my left arm won’t stop shaking and, you know, I’m missing chords.” That was then. Now he says he, “wants to say yes to anything to do with music,”

Produced by Jeff Wysosky, Anxiety: The Lay Dog Sessions features a lineup of supporting players that reads like a who’s who of the Greensboro music scene. Laura Jane Vincent, Emily Stewart, Erin Hayes and Ali Fox contributed background vocals and play various instruments. Kelly Frick can be heard on violin while Ben Singer and Jerrod Smith banged out some drum tracks.

“And Taylor Bays came over to play synth on a recording,” Matty adds about our recently departed, beloved musical Puck. “Specifically he had this old, POS synthesizer. Some of the keys are actually broken off. He also brought over a really nice keyboard because he had a bunch of gear but I was like, ‘Play the piece-of-crap one, I love it.’ And Jeff made it sound nasty and distorted. While he was there I got Taylor to sing lead with me on a couple of songs. We had fun.”

This is only one of the recording projects Matty’s involved with currently. “I went from, ‘I don’t know if I can be a musician anymore’ to recording three records this year,” he says. “Myself, Laura Jane Vincent, and Ben Singer have been playing at Common Grounds every Wednesday for the last year. We love it. We said, ‘We’ve got to record this.’ So we just went over to Ben Singer’s where he’s got a bunch of cool recording equipment. It has a very live feeling.”

Longtime collaborator Laura Jane Vincent, who has her own solo musical forays, describes Matty’s style as, “Post-folk if you will. It’s not really your traditional love stories or even character stories. I like when I can’t predict where someone’s lyrics are going to go and I feel like Matty is like that. He’s a great writer and very comfortable performing in front of people.”

That ease in front of an audience may be because Matty has been hosting a Tuesday night Open Mic Night weekly for the last 17 years, currently at Westerwood Tavern. “I really love meeting people at Open Mic,” he says. “I feel like we’re instant friends. Like meeting another band on tour. It’s the best.”

Megan Jean and Vern Kly are producing Matty’s next release, engineered by Tom Troyer at Black Rabbit Audio. “They have some really cool ideas,” Matty says. “They say it’s going to be an Indy pop dance record. So I’m really excited about that.”

Anxiety: The Lazy Dog Sessions is available on all the usual digital platforms like Spotify and Amazon. Meanwhile, Matty’s taken up the ukulele, partly for therapeutic reasons, “It’s good for your brain to learn new instruments.”

* * *

The Tate Street Festival, the city’s longest running street fest, will be held on October 19th from 1 to 7 p.m. Jaime Coggins, who accompanied me for that Double Oaks concert, has been organizing this celebration of local music, arts and crafts since 2001. She tells me it originally got underway in the 1970s, billed as the Noon To Moon Festival, put together by the late Jim Clark. After a hiatus in the 1980s, it’s been a yearly tradition since at least the late-1990s. See you there, Eye never miss it.

* * *

What was once proudly a dive bar is now a live bar, risen like the proverbial phoenix, soaring higher than ever. Dusty Keene, proprietor of the aforementioned Common Grounds, has resuscitated the Flat Iron on Summit downtown. Opening in 1993, for the next two decades the Flat, as it’s affectionately known, was one of the city’s preeminent watering holes.

A dearth of medium-sized music venues prompted Keene to pry open the doors to this venerable institution, giving the place a concretely solid facelift. “When I was growing up in Greensboro, I discovered the music scene here when I was like 14 years old,” Keene tells me about the Flat. “I couldn’t believe how many great bands there were. Then this sort of odd, strange drought happened where there was not really a place for local bands to come up and get their start.”

The Flat Iron has a well-deserved reputation as a musical Valhalla: “When you walk in, you can kind of feel the history,” Keene says, and he’s right. “The idea is to attract national and regional acts then pair them with local talent. Bands here get more exposure, the other acts get more exposure . . .” After a month to work out any kinks, grand opening was just a few weeks ago. Step back in time to see the future.

* * *

Finally, you have the opportunity to enjoy the dulcet tones of Em and Ty on Sunday, October 13th, staged on the back lawn at Double Oaks. See for yourself what a magnificent corner of the world this is. Based in Greensboro, along with their solo efforts, this married folk/rock duo have been performing together for the last five years. Reserve tickets at double-oaks.com. Beer, wine, and homemade brick-oven pizzas are available for purchase. OH

Billy Eye is O.G. — Original Greensboro.