Simple Life

A Fragile Blue World

by Jim Dodson

While digging out an old flowerbed the other day I found, of all things, a beautiful blue marble long buried beneath a foot of earth.

I decided it was either evidence of a lost race of marble-playing pioneers or simply belonged to kid who lost it in the dirt when our house was built in the early 1950s. That kid would now be at least 70 years old.

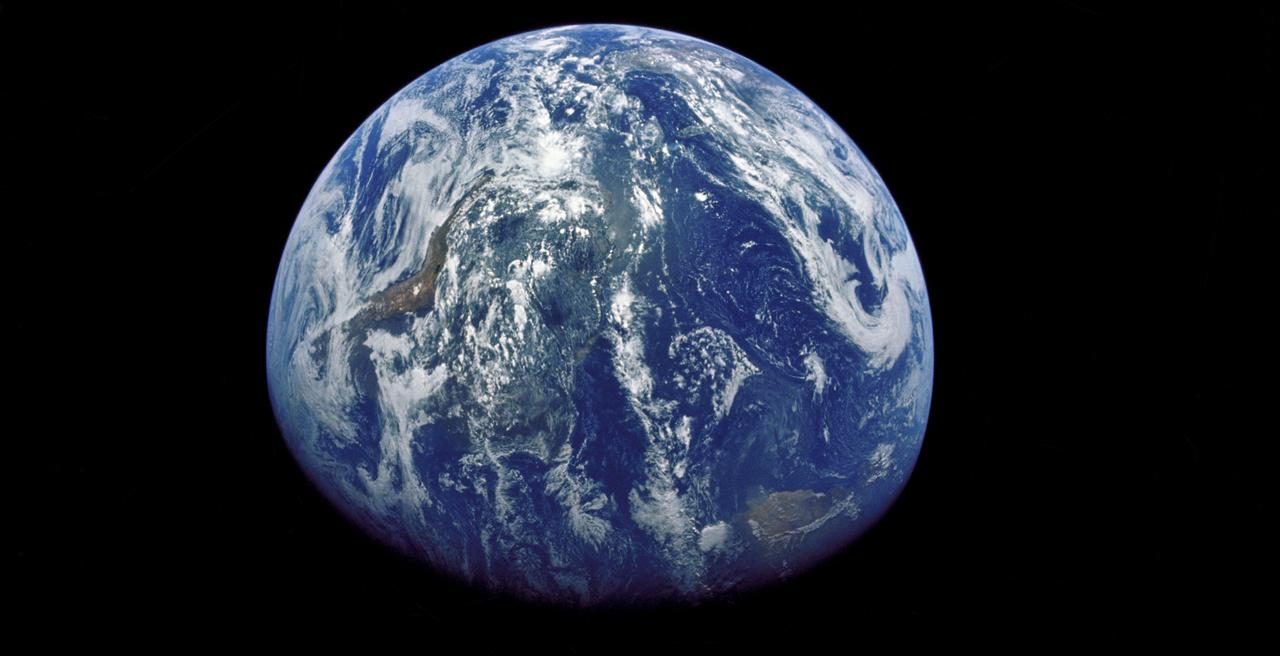

Either way, this beautiful blue marble, resting in the palm of my soiled palm, reminded me of an image of the planet taken by the crew of the final Apollo mission as they made their way to the Moon, a photograph dubbed the “Blue Marble” because it revealed a fragile blue world that is home to “billions of creatures, a beautiful orb capable of fitting into the pocket of the universe,” as NASA elegantly put it. Looking at the beautiful blue planet Earth from space, one astronaut was moved to say that it appears so peaceful and calm it’s almost impossible to believe it is a world endangered by poverty, war and disease.

Some experts believe marbles are the oldest toys on Earth, found by archeologists in the ashes of Pompeii and the tombs of ancient Egypt, mentioned in Homer’s The Odyssey and Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Even the Founding Fathers of America were known to play a mean game of marbles during idle moments making up a nation.

The earliest marbles were made of dried and molded clay. In the mid-19th century, however, a German glassblower invented a pair of special scissors that could cut and shape molten glass, making glass marbles affordable for the first time. Glass marbles quickly dominated the world toy market, particularly after industrial machines made them more efficiently, dramatically lowering the price. “Valued as much for their beauty as the games played with them,” the National Toy Hall of Fame notes, “marbles inspired one 19th-century enthusiast to describe the twisted spiral of colored filament in glass marbles as ‘thin music translated into colored glass.’

Because my family was always on the move during my first seven years of life – following my father’s newspaper career across the deep South – I had few if any regular playmates and plenty of time to fill up during endless summer afternoon in small southern towns. Adventure books, marbles and painted Roman armies filled quiet hours when only the lonesome sound of cicadas in love filled the hot, still air.

Everywhere we lived from Mississippi to South Carolina, however, I always managed to find myself a cool and comfortable patch of earth beneath a porch or a large tree where I played out the Peloponnesian War or shot marbles in a large ring scratched into the dirt.

I got pretty good at shooting marbles, often whipping my dad when he came home from work and stepped outside with a cold beer just to see if I had any interest in coming to supper, squatting to play me a quick game in the dirt. The object of the game we played was to knock as many marbles outside the ring without having your “shooter” wind up outside the circle. I forget who told me that it was good luck to play with a marble that matched the color of your eyes. My favorite shooter was blue. So are my eyes, I’m told.

I could spin and skip marbles like nobody’s business in those days, or so I like to think, and even carried a small sack of my favorite marbles wherever my family went on vacations or – worse — visited elderly relatives. Politely excused, advised not to wander far, I could slip outside and find the nearest patch of earth for a little marble shooting practice in no time flat.

Marbles was the first game I ever fell I love with. But not the last.

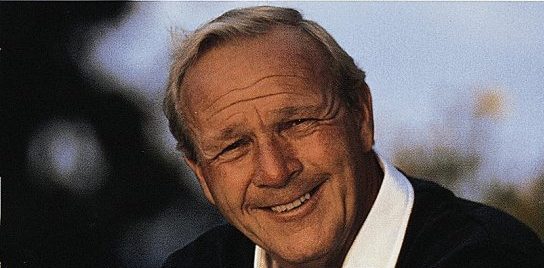

For along came the spring and summer of 1964. I watched Arnold Palmer win his fourth and final Masters green jacket on TV and immediately took to swinging a golf club in the yard, within a year or so fashioning a list of things I hoped to do in golf. At the top of the list was my goal to someday meet the new King of Golf.

That summer, however, I made the Pet Dairy Little League team and began reading about Brooks Robinson, the “Human Vacuum Cleaner” in the sports pages. Robinson played third base for the Baltimore Orioles. I laid hands on an official Brooks Robinson fielder’s glove, vowing that in the unlikely event that I didn’t grow up to be the next Arnold Palmer I might become the next Brooks Robinson instead.

In effect, I lost my marbles that summer of ’64 – or at least put them away forever.

Arnie won the Masters and Robinson had his best season offensively, hitting for a .318 batting average with 28 home runs. He also led the league with 118 runs batted in, capturing the American League’s MVP Award and his tenth Golden Glove. In the American League MVP voting, Robinson received 18 of the 20 first-place votes, with Mickey Mantle finishing second, much to my Uncle Carson’s delight.

He’s the one who took me to my first Major League ballgame when I got sent up that summer to spend a week with my mother’s big blond sisters and their husbands in Baltimore. Uncle Carson was a giant Irishman who worked at the Kelly tire factory and had a pair of season tickets to “the Birds,” as he fondly called the hometown Orioles. He detested Mickey Mantle. “I’d like to knock that smug smile that overpaid showboat’s kisser,” he growled during the pre-game warm-ups as both teams took the field in old Memorial Stadium.

Uncle Carson’s seats were a dozen rows back along the third base line. He encouraged me to bring along my new Brooks Robinson fielder’s glove, promising that I could get it autographed by “Human Vacuum Cleaner” himself during warm-ups.

Sure enough, when Robinson appeared on the field, stretching and chatting with other players, including detestable Yankees, Uncle Carson sent me scurrying down to the dugout where other kids were hanging over the railing in search of autographs.

When Robinson ambled over, I showed him my new mitt and asked him to sign it.

He obliged. “Sure, kid. Where you from?”

In truth, I have no memory what he actually said to me. I was much too tongue-tied and star struck at that moment.

Up in the stands, however, as Mickey Mantle sauntered past, Uncle Carson cupped his massive hands to his mouth and hollered, “Hey, Mantle! You’re a stinking bum! You couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn if they pitched underhand to you!”

For the record, I’m not sure this is exactly what Uncle Carson yelled at Mickey Mantle, either. But it’s certainly within the ballpark, as they say, because Uncle Carson was a world-class heckler, a one-man leather lung, the ultimate obnoxious Oriole. Mickey Mantle just laughed and kept walking.

When I got back to our seats, Uncle C was buying cups of beer from a vendor.

“How old are you now?” He asked.

“Eleven,” I answered truthfully.

“That’s good enough.” He handed me a National Bohemian beer, my first ballpark beer. As we stood for the national anthem, placing a massive paw over his heart, he added, “By the way, Squire, your aunt Leona and mom didn’t need to know everything that happens at the ball park. Including Natty Boh. You follow?”

I nodded and sipped my beer. It was great to be alive.

Funny thing about life on a spinning blue marble, though.

Despite my best efforts, I failed to become the next Arnold Palmer or Human Vacuum Cleaner. But at least I grew up to collaborate with The King of Golf on his bestselling memoirs, becoming a close friend of the game’s most charismatic figure.

Some years ago, I even had the chance to tell Brooks Robinson about my Uncle Carson’s remarkable leather lung at a dinner where I was the guest of honor for my sports journalism and books. The event’s host had secretly invited the greatest third baseman of all time to sit beside the honoree, who was nearly as tongue-tied and star struck as he was in 1964.

“I think I remember your Uncle Carson,” Robison told me with a laugh. “Or at least a few hundred other guys like him – especially up in Yankee Stadium. Those loud mouths made your uncle look like minor league player, I’m afraid.”

We had a fine time chatting about the Oriole’s golden seasons and lamented their cellar-dwelling ways these days. In 1966, Robinson finished second to teammate Frank Robinson in voting for the American League Most Valuable Player Award. But the Orioles went on to win their first World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

In the 1970 post-season, Robinson hit for an average of .583 in the American League Championship, leading the way to a second World Series title for the Birds. It was Robinson’s defensive prowess, however, that earned him the Series MVP and prompted Reds manager Sparky Anderson to quip, “I’m beginning to see Brooks in my sleep. If I dropped this paper plate, he’d pick it up on one hop and throw me out at first.”

At the end of his final season in 1977, having collected 16 Golden Gloves as baseball’s top defensive player, Robinson’s number 5 was officially retired. Five years later he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on the first ballot. “It all seemed to pass so quickly,” he told me that night we ate supper together. “But my goodness what great memories!”

A few years after this encounter, I sat with Arnold Palmer just weeks before he passed away, catching up on his family and mine, even drifting into the subject of boyhood dreams. He told me a story that I’d heard before about how as a little kid he dreamed that he might someday become a famous football star – to impress certain girls. But then the golf bug bit him.

“I’m glad you stuck with golf,” I said.

He already knew that once upon a time that I’d hoped to become the next Arnold Palmer but had an alternate plan to be the second coming of Brooks Robinson if that failed to pan out. I even told him about.

The King smiled. “I think you got pretty much what you wanted,” he said.

“So did you.”

I even told him about Uncle Carson and his leather lung.

The King chuckled. “I’m glad you never brought him to the golf course.”

As another summer looms, the world in 2020 is a very different place.

Stadiums and ballparks across the world are sitting empty, haunted by echoes of seasons past.

For the moment, memories are all we’ve got. For nobody can say when – or even if – the games will begin again anytime soon.

Having lost all my marbles but found a blue one buried in the earth of my own garden, I’m probably where I should be at this moment and time on a fragile blue planet, lucky to have a world I can hold in my palm of my hand, and remember.

Jim Dodson’s latest book, The Range Bucket List, tells these stories and other tales from his long journey through the world of golf and sports.