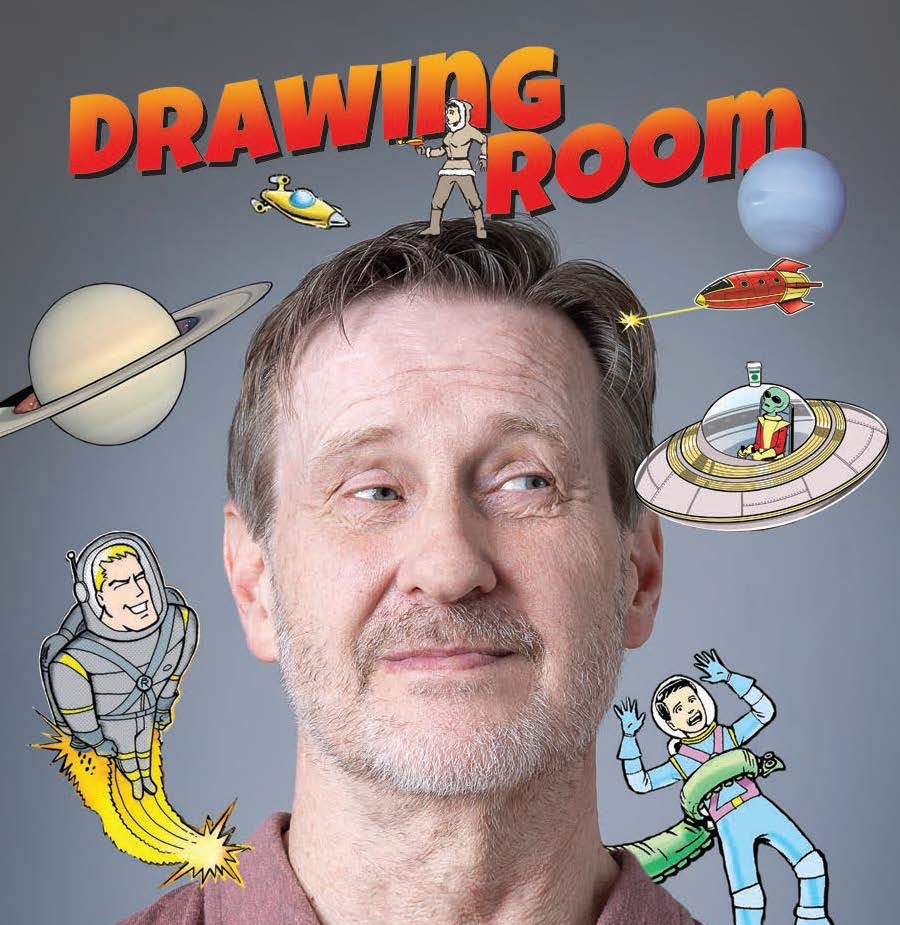

DRAWING ROOM

Greensboro cartoonist Tim Rickard reflects on two decades of Brewster Rockit

By Maria Johnson

Photograph by Bert VanderVeen

Someone sets a cup of coffee on the roof of their car.

They get distracted.

They drive off, cup still on top of the car.

This all-too-human scenario tickles cartoonist Tim Rickard as he picks up his stylus and starts doodling.

What tickles him more is the possibility of this uh-oh moment happening in outer space, specifically in the world he has created for his syndicated comic strip, Brewster Rockit: Space Guy!, which is named for its protagonist, the strikingly handsome and equally clueless commander of the space station R.U. Sirius.

In the 21 years since Brewster and his crew of cosmo-nuts first appeared in publications around the country, Rickard has blasted them into deep-space silliness thousands of times. He draws six strips a week: one for every weekday, plus a standalone for Sunday.

The strip appears in the funny pages of major publications, including The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

While Brewster is a tyke compared to some longstanding cartoons — Rickard’s broker, Tribune Content Agency, also represents stalwarts Dick Tracy, Broom-Hilda, Gasoline Alley and Annie — the commander’s longevity is a stellar achievement in the universe of syndicated strips, where the average feature lasts 10 to 15 years.

One key to Brewster’s endurance: a fan base that includes the professionally spaced-out.

“I love the way he manages to be informative and funny,” says Marc Rayman, the chief engineer for mission operations and science at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA.

He’s talking about Rickard, whom he credits with otherworldly talent.

Brewster is another story.

“Brewster never intends to be funny,” adds Rayman. “He’s not smart enough to be funny. But I admire his biceps and his jaw.”

Where would the ill-fated coffee cup be? Rickard wonders how to transport the commuter gag into Brewster’s world.

He sits at a desk in his home office, where he has worked since 2020, when he was laid off by Greensboro’s News & Record newspaper after 27 years as a staff artist.

He slides a stylus across a graphics tablet.

Lines appear on the 24-inch screen in front of him.

He roughs out the R.U. Sirius and places a coffee cup on top of the space station.

Nah, he decides. The cup is too small relative to the station.

Rickard, who resembles a salt-and-pepper version of the boyish Brewster, deletes the scene and starts over.

He draws a pointy-nosed rocket zipping sideways through space and outlines a coffee cup on top.

Nope. Still not right. Delete.

His mind and his hand keep moving.

He was a scribbler.

You know the one: The kid who draws on every napkin. Every flyleaf. Every sidewalk.

Rickard’s dad liked to tell the story of going into an Owensboro, Ky., cafe in the wintertime and watching his son, then 4 or 5, draw with his finger on the steamy windows.

Rickard, 66, who has been a member of MENSA, the high-IQ club, for about 40 years, looks back on his younger self with a mixture of humor and compassion.

Several years ago, he says, he realized that he’s probably on the high-functioning end of the autism spectrum, along with many others who excel in the visual arts.

As a youngster, he was plenty smart intellectually, but talking with people face-to-face was challenging. Communicating with pictures — with the chance to draw in solitude, erase and redo — was much easier.

He went to Kentucky Wesleyan College to study art, with an eye toward advertising. A couple of internships and freelance jobs later, he decided that working for a newspaper, on the editorial side, would offer more variety and freedom.

He joined his hometown paper, the Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer. A couple of years later, seeking a bigger paycheck, he signed on with the News & Record. His portfolio expanded to include courtroom sketches, editorial cartoons and illustrations for stories that did not lend themselves to photographs.

He also started a weekly comic called Joke’s on You, a single-frame feature that showed characters in situations with no dialogue. Readers competed to provide the winning captions.

Summerfield veterinarian Tim Tribbett won 32 contests, more than anyone. One of Tribbett’s favorites showed a mama bear and baby bear gazing at a bearskin rug on the floor of their home.

“Couldn’t we just keep a photo on the mantle?” the cub asks in Tribbett’s caption.

Every week, Rickard sent the winner a signed, printed copy of their entry along with a note of congratulations. The strip provided a community for participants.

“We never met, but we felt like we knew Tim, and we knew each other a little bit,” says Tribbett.

When Rickard left the newspaper during COVID, about 20 faithful contestants threw him a party at a local park. They brought a cake topped with an edible image of Rickard’s work.

“The contest meant a lot to us,” Tribbett says.

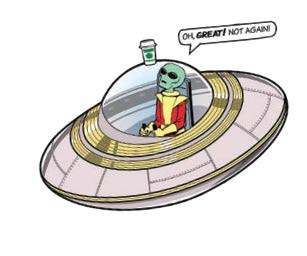

Rickard is still pondering where to put the coffee cup.

Atop a small flying saucer?

That would be comparable to a car.

He sketches a small, sporty saucer with a clear dome. The coffee cup appears on top.

Bingo.

More questions blossom in his head: Who is inside the saucer? How many characters?

Is there dialogue between them?

Two aliens appear inside the bubble.

“You left your coffee on the roof again?” one says to the other.

Rickard studies the scene.

It’s OK.

But just OK.

Drawing a strip that appeared in funny pages nationwide — that was the goal.

Rickard started submitting ideas to syndicates when he was in high school.

Rejections piled up, but some contained a grain of encouragement.

“Not bad.”

“You’re a good gag writer.”

It was enough to keep him going.

He knew his ideas were derivative, hewing too closely to existing strips. He needed something fresh.

Long a fan of Star Trek, Star Wars, the Marvel catalog and monster movies, he was at home in fantasy worlds. But Earthly wisdom held that space-based comics didn’t fly, and Rickard was loath to try sci-funny until rejection pushed him to give it a whirl.

“I figured if I was gonna fail, I might as well fail doing something I want to do,” he says.

That’s when Brewster came to visit. Rickard was in his early 40s.

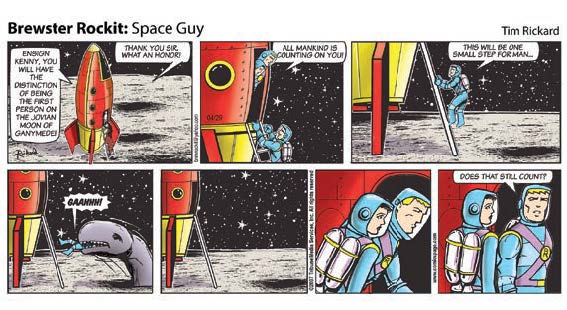

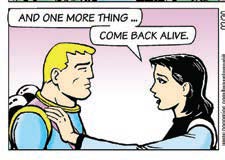

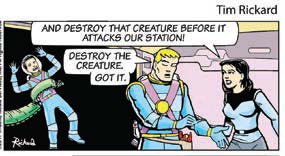

Drawing late at night while his family slept, he invited the hapless captain into his head to play. Soon, Brewster showed up with other characters, including Brewster’s very competent wife, Pamela Mae Snap; Dr. Mel Practice, the station’s crazed chief scientist, whose inventions include the Procrastination Ray; and Dirk Raider, a former member of Brewster’s Goodguy Knights who had crossed over to the sinister Microsith corporation.

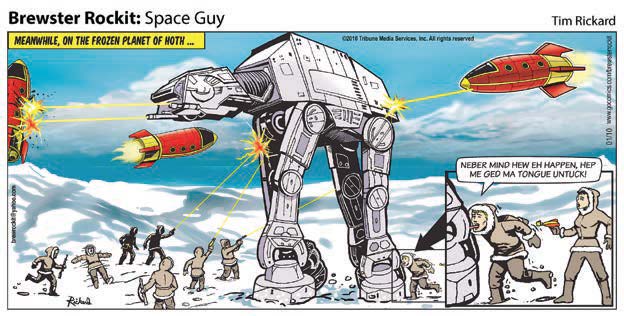

Rickard drew his characters in a realistic style reminiscent of soapy comic strips Steve Canyon, Mary Worth and Rex Morgan M.D.

His concept — that Brewster and his goofy sidekicks protected the Earth from evil— was funny on its face, and it provided a lot of room for storylines.

In early 2003, Rickard sent samples of Brewster to three syndicates. Two replied with nays. The third did not respond. Rickard assumed that meant “no.” He let go of his dream.

A couple of months later, the third syndicate replied. They wanted to see more.

Rickard sharpened his strip according to the editors’ suggestions, and Brewster joined the fleet of Tribune comics in July 2004.

NASA’s Rayman saw the strip in the Los Angeles Times soon after it launched.

Brewster’s mix of scientific literacy and everyday nincompoopery impressed him and his real-world rocket scientist colleagues.

“Many of Tim’s comics — in fact, most of them — don’t have anything specifically to do with space,” Rayman says. “Like any creative artist, he uses the context he has created to cover many different subjects.”

Still, Rayman admits, he’s thrilled whenever Brewster mentions a mission that Rayman is actually working on, as happened in 2007, when the strip referred to DAWN, a probe that investigated the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Rayman contacted Rickard to suggest, in jest, that he should ask Brewster and crew for advice. Rickard was game. He incorporated Rayman and a legit question into a strip. Several characters offered lame words of wisdom.

Rickard and Rayman have been collaborating ever since. Rayman fact-checks some of the weekday strips, and they share responsibility for Rocket Science Sunday, an occasional educational version of Brewster.

“He’s extremely open to my comments and feedback,” says Rayman. “There’s no ego to hold back the quality.”

Or the buffoonery.

In Brewster’s world, Earthlings can escape gravity but not their foibles.

“The strip never feels like it’s talking down to anybody because the characters are so flawed and stupid and lazy,” Rickard says. “The reader is always in on the joke.”

Ideas come from all directions: news, science, popular culture.

Sometimes, Rickard’s own life seeps into the frames. After he had his first colonoscopy, so did the character named OldBot.

Once, an enemy storm trooper asked his daughter for help with his phone — a copy and paste of Rickard asking his own daughters for technical assistance.

Also, Brewster made a list when Pam asked him to complete more than one task.

“That was literally a conversation with my wife and me,” Rickard says.

In 2010, he and his syndicators traveled to Hollywood to pitch an animated movie based on Brewster, who appeared in 150 markets at the time.

Nothing came of the meetings, but the comic kept cruising.

Last year, The GreenHill Center for NC Art included more than a dozen Brewster pieces in a show of science fiction works by artists statewide.

Rickard relished the sight of Brewster on the walls of the tony gallery.

“He seemed totally out of place,” he says, chuckling.

Where might Brewster materialize next?

Rickard shrugs. He’d like to do another best-of book. A 2007 paperback collection subtitled Closer Encounters of the Worst Kind is out of print but fetches healthy resale prices.

As for the daily offerings, Rickard repeats his industry’s biggest non-secret: newspapers and other traditional customers are dwindling. The News & Record dropped the strip after they laid off Rickard.

One day in the not-so-distant future, Rickard says, Brewster might cease to dwell on paper, his original home, and live only online. Already, the strip appears at gocomics.com, an internet-only repository of cartoons past and present.

In a way, a total shift to cyberspace would make cosmic — and comic — sense.

Rickard says Brewster and his creator are ready to adapt.

“It’s always been a forward-looking type of strip, so the fact that that would be the inevitable home for him would seem appropriate,” Rickard says.

He deletes one of the aliens in the flying saucer.

The one-liner, “You left your coffee on the roof again?” disappears, too.

Only the driver of the saucer remains.

Rickard re-draws the alien’s head. Now he looks up at the cup through the clear roof of the craft.

A thought bubble appears.

“Oh, no. Not again.”

Rickard sits back and puts his stylus down.

That works.