DREAM HOME

Dream Home

A Loewenstein lives on in Irving Park

By Billy Ingram • Photographs by Amy Freeman

When newlyweds Daniel and Kathy Craft set out in search of their dream home, one both idealized yet narrowly defined, it may have seemed like that impossible dream enshrined in song. What they had in mind was a place that offered a warm hearth and an enriching environment where they could raise a family, but the type of home they desired wasn’t being built anymore, and the remaining ones were being eradicated at an alarming rate. They were longing for a Loewenstein.

In those rare instances when Triad realtors happen across a listing for a “Loewenstein,” the name is spoken in revered tones. There were other mid-century architects crafting magnificent homes locally and across the Southeast, celebrated artists held in just as high regard — Charles C. Hartmann and Harry Barton being obvious options — but for sweeping super-structures limited solely by one’s imagination and, only occasionally, the laws of gravity, Edward Loewenstein was, and remains, in a class unto himself.

The unfolding of the 1950s ushered in an era of unprecedented prosperity buoyed by an abundance of unrealized real estate, an atmosphere where there could be no greater testimony to a family’s success than the home they had designed and constructed for themselves. And no address came packaged with more prestige for platforming those affluent architectural assertions than a cautiously expanding Irving Park neighborhood street encircling the Greensboro Country Club, established in 1909.

A disciple of the Modernist movement typified by Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra and other avant-garde West Coast architects, Edward Loewenstein graduated from Chicago’s Deerfield Shields High School and MIT with a B.A. in architecture in 1935. He established his Greensboro architectural firm in 1946 after having served during WWII and marrying Francis Stern, stepdaughter to denim impresario Julius Cone. He was determined to break away from the Arts and Crafts, Mission Colonial and Tudor Revivals going up north of downtown.

After completing a dozen or so conventional dwellings, as luck would have it, he was approached in 1950 by a young couple, Wilbur and Martha Carter, who had three children and a hankering for a homestead that would instill an air of distinction on their heavily wooded, 1.28-acre lot facing Country Club Drive and extending back to Cornwallis.

Given a choice between two wildly divergent designs, one a Georgian Revival fitting snugly into the neighborhood’s stately but somewhat staid motif, the Carters chose the more radical schematic Loewenstein presented them with. “I think there were other houses in Greensboro that had Modernist tendencies, but it seemed he was the only one at the time that was [dedicated to] it,” says Patrick Lee Lucas, author of the definitive book on Greensboro’s Modernist maestro: Modernism at Home: Edward Loewenstein’s Mid-Century Architectural Innovation in the Civil Rights Era.

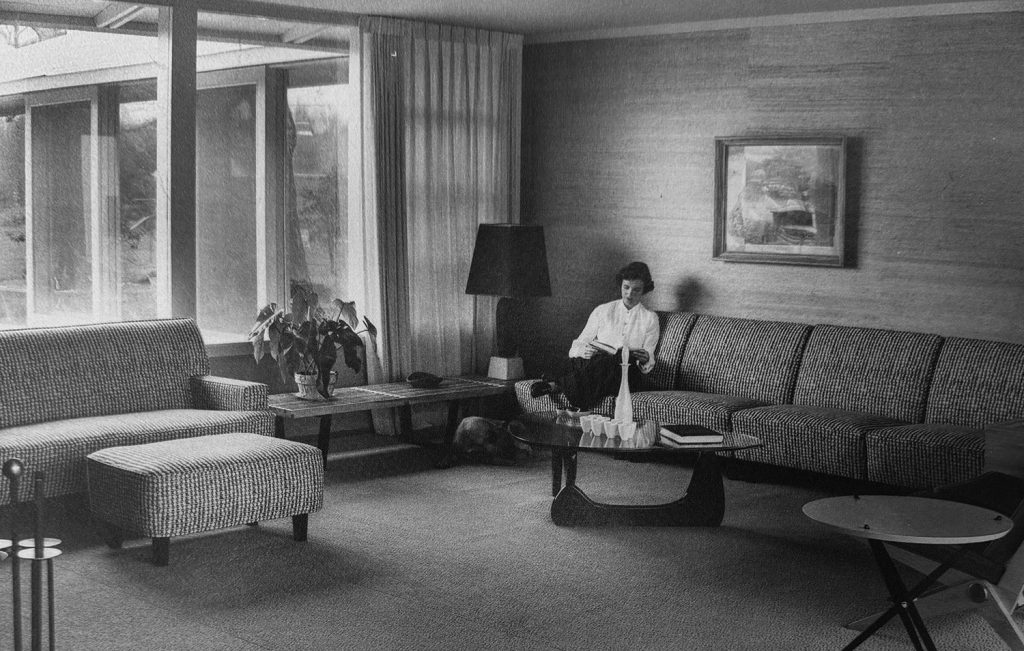

Following the precepts of international modern style, the Carters’ house was defined by a flat roof, an open floor plan, curtain windows and minimal ornamentation. Architects of the time were guided by the “rule” that “form follows function,” which prompted designers to consider what a building should achieve for the user before what it should look like. Blueprints called for a horizontal, L-shaped structure fronted with a low-pitched roof atop a screened (eventually glass) solarium, which featured bluestone flooring that stretched into the central living room. Obscuring an already sunken, single-leaf front door, an 8-foot-high brick wall extended from the front yard into the home for a short way to distinguish the bedroom corridor from communal space.

Toward the rear, hidden storage and built-in bookshelves abounded, and at the base of the windows inside the den a brick planter was enclosed. Back-to-back fireplaces were embedded in a load bearing wall facing both the living room and den. The spacious kitchen was floored in 9-by-9-inch, brown-and-marble-patterned, vinyl-asbestos tiles made by Armstrong. Employing industrial-use tiles and natural stone floors indoors were uncommon home accoutrement. The children’s rooms were connected via a Jack-and-Jill bathroom.

Rather than clearcutting, as was the custom, all of the imposing oaks on the property remained in place. “Loewenstein seemed particularly adept at using underutilized lots in Irving Park,” Lucas points out. “These were the tree lots that no one wanted or they were sold off from a bigger parcel as the neighborhood further subdivided.” Gravitating toward rugged grounds with unusual features, says Lucas, “Part of his goal, both from a Modernist sense but also from a sensitivity to the environment, was to build around the trees.”

“Of all the houses that he designed, it’s the most unusual in that it has two living rooms next to one another,” Lucas notes. “One was essentially an outdoor room, so it meant that there were times of the year it couldn’t be used because it was just so cold and hard to heat in the ’50s.” The resulting perception was an innate spaciousness that gave the sense of being outside while inside the home, its wide-open interiors defined not so much by walls as where people chose to congregate.

The Carter abode was such a radical departure from the norm it was practically an affront. “Some of the neighbors were like, what? And others were like, this is cool,” Lucas states. “So there was a little tug of war in that sense.” In correspondence concerning what he referred to as his “Dream Home,” Loewenstein lamented that he “received violent comments in both directions from neighbors and friends.” The Carters themselves were pleased as “they wanted it to be not something traditional,” Lucas reiterates.

Vindication arrived after the house won an American Institute of Architects North Carolina Design Award in 1951, was featured in Architectural Record in 1952, and then bestowed a 1955 Merit Award from Southern Architect magazine. Resistance to Loewenstein’s futuristic fancies melted as a subsequent Modernist home was taking shape on Princess Anne Street in nearby Kirkwood, where homeowners petitioned the Greensboro Zoning Commission to allow for a departure from the contemporary Cape Cod conformity sanctioned by its neighborhood planners.

From the beginning, Loewenstein was the first in North Carolina to hire Black architects. “Some had employed African American draftsmen before World War II, but he was the first to do it in a major way,” Lucas points out. Many, like Clinton Gravely and W. Edward Jenkins, went on to great acclaim in Greensboro with their own firms. “It was a form of protest or nonconformity in terms of the way that he operated, employing these guys who wouldn’t have an architecture firm to work for because there wasn’t one that would hire them.”

Lucas posits that marrying into the influential Cone family allowed Loewenstein to buck the system “and probably not suffer the consequences of other societal forces relative to how the rest of us had to operate.” Hailing from Chicago, where race relations were far less volatile, Lucas muses, “Maybe he was doing what he was doing and just let the chips fall where they may.” Or, perhaps, being the only prominent Jewish architect in North Carolina, it was a logical extension of his own status as an underdog.

With Loewenstein’s reputation and workload steadily growing across the Southeast he took on a partner, Robert A. Atkinson Jr. In 1950s in Irving Park alone, the firm of Loewenstein-Atkinson was responsible for ground-breaking Modernist designs such as the sumptuous Ceasar and Martha Cone house on Cornwallis (demolished for a cul-de-sac in 1994), the Sidney and Kay Stern residence at 1804 Nottingham, UNCG’s 1959 Commencement Home at 612 Rockford, the John and Evelyn Hyman home at 608 Kimberly Drive and the game-changing Robert and Bettie Chandgie hybrid two blocks away at 401 Kimberly.

Embracing Modernism allowed for a lessened emphasis on interior decoration. “What we’re going to do is just celebrate nature without having to actually reproduce it inside,” Lucas maintains about the minimalist philosophy, creating frameworks adaptable to any aesthetic. One can’t help but wonder what it was like back in the 1950s, before suburban street lamps dulled Irving Park’s nighttime skies, the warmth inside these homes contrasting with nature’s soaring flora bathed in moonlight refracted through panoramic glass apertures.

In 2004, with three kids in tow, the Crafts became only the second owners of Loewenstein’s self-described “Dream House” he had crafted for the Carters, but not without considerable effort. “We’d been looking for years,” Kathy recalls. The journey home began when they were newlyweds, but didn’t end until seven years later. “We were 28 years old and we just couldn’t turn around and buy a Loewenstein at that time.” Still, they researched, attended open houses and watched frustratingly as, one after another, Modernist monoliths fell out of favor and were leveled in favor of developing the land they occupied.

Fate stepped in after the Crafts met Lee Carter at what had been his childhood home. Kathy knew after just a few feet into the front door that this was the one. None the less, Carter wasn’t exactly a motivated seller. Witnessing what had happened to other comparable properties, he only, months later, made the decision to allow the family home to change hands, but with one stipulation — that it not be desecrated or demolished. “It was sort of destiny, it was the right timing and it was the right house,” Kathy says.

In the suitably spacious backyard, the Crafts discovered the Carters had installed a small horse stable and utility building. Structural alterations undertaken by the Carters decades earlier, overseen by Loewenstein, included decreasing the width of the wall alongside the front door while increasing the length of the roof covering the solarium. In the 1980s, brickwork inside and out was painted white. A pantry door off of the kitchen still retains the Carter family’s important names and contact information scrawled across it, reminders of a time when only five numbers were required to dial neighbors.

Foundational tweaks the Crafts have instituted are minimal. All of the window panes have been replaced and the vinyl-asbestos kitchen flooring was removed in favor of a terrazzo-like porcelain tile. After seven decades, a smattering of those old growth trees have been uprooted by necessity, flooding the home with natural light. “I never turn on a lamp until the sun goes down,” Kathy says.

In the early 2000s, Kathy owned the Eastern Standard Gallery located in downtown’s Southend community, where she showcased, among many other exemplary artists, her brother-in-law Michael Coté’s furniture. In fact, he constructed their intricately inlaid wood dinner table. “He was not trained, never schooled. He just picked up woodworking and made that table,” says Kathy. Redeploying the matching high back chairs for accents, the Crafts instead assembled table-side a half dozen transparent, Baroque-influenced Philippe Starck Ghost Chairs with curved armrests. As actress Katherine Hepburn famously attested, “Men are unhappy sitting at a dining room table if their chairs don’t have arms.”

Behind that table, imbuing an Asian influence, is an a four-panel vintage Baker Furniture screen that Douglas Freeman painted for Daniel’s birthday in 2010. A happy match with what the Carters had acquired in 1964 and left behind that adorns the den, a Japanese byōbu from MoMA depicting Heian-period courtiers leading a formal procession. “That is actually paper adhered to the wall, then framed,” Kathy explains.

The solarium is punctuated by a painting awash in muted tones, “an abstract of the marsh by Walter Greer,” says Kathy, “a well-known artist from Hilton Head Island. Dad loved his work.” Nearby are two Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Barcelona chairs and an ottoman, reflexively reflecting an overall retro sensibility to the decor, embellishments emblematic of a sense of playful permanence and space-age proportionality this home embodies.

The Crafts’ three children have graduated college and scattered to careers in various locales, but this in no way feels like an empty nest. If anything, a welcoming environment for a potential influx of grandkids.

The mid-century Modernist movement was, for many, an optimistic harbinger for the wondrous World of Tomorrow promised us by the 1939 World’s Fair, Disneyland and Reddy Kilowatt (“Live better electrically!”). Finished in 1954, Loewenstein’s own home on Granville Road features a driveway long and wide enough to land a flying car comfortably, should it come to that.

In his waning days, Frank Lloyd Wright was quoted as saying, “The longer I live, the more beautiful life becomes. If you foolishly ignore beauty, you will soon find yourself without it. Your life will be impoverished. But if you invest in beauty, it will remain with you all the days of your life.” Loewenstein was more laconic: “Dedicated architects die unhappy. They never get to unleash creative juices because of pressure to please clients.” He gets right to the heart of what gives the Carter House its cultural significance, so cutting-edge for the period — nobody knew enough about the direction the upstart architect was headed to get in his way.

In the end, Loewenstein’s instinct for “bringing the outside inside” backfired in terms of longevity. Eventually, some would argue inevitably, the spacious landscaping these houses were integrated into far exceeded the commercial value of the structures.

“It used to be,” Lucas says, “if you were one of these Modernist houses designed by this weird guy, Loewenstein, no big deal. We’ll just tear it down and build something bigger there.” Now the name conveys a level of esteem in the way Rolex, Ferrari and Tiffany have become synonymous with style and stature. “Most of the calls I still get are from realtors trying to prop up their property with a Loewenstein connection. So it’s kind of moved on in that regard.”

As realtor Katie Redhead related to me a few years ago about the current marketplace mindset regarding Loewensteins, “We started seeing homes that were in Westerwood, a house on East Lake Drive — let me tell you, those houses went off the charts, people went nuts. Right now we’ve got such a high demand, if one did come on the market, I think it would be well received. And I probably wouldn’t have said that 10 years ago.”

As for the Crafts, they won’t be selling any time soon.