FROM CENTRAL PARK TO FISHER PARK

From Central Park to Fisher Park

A big-city transplant brings verve to a 100-year-old bungalow

By Maria Johnson

Photographs by Amy Freeman

About a dozen years ago, Richard Peterson was walking down Greensboro’s North Eugene Street where it feathers from the commercial glassiness of downtown into the residential coziness of Fisher Park, when he saw a 90-some-year-old lady.

She was faded and outdated.

But she had class.

And good bones.

Peterson, once a jet-setting New York hair stylist with A-list clients, saw what she could be. So he did what he usually does: He made the most of her attributes, which, in this case, included a deep front porch, cedar shakes and rosy-brick walls stacked in a Flemish bond pattern, with alternating long and short sides in every course.

In the decade-plus since he bought the compact cottage, Peterson has artfully used tones from that brick palette — ranging from salmon to russet — to splash the property, inside and out, with blushing accents balanced by calming greens.

Now, especially in the spring, when the home’s English-flavored garden froths with blossoms inside the peaked waves of a boxwood hedge, the old Craftsman dame, petite though she may be at 1,000 square feet, still turns heads.

Her show stopper: the crown of pink Eden roses climbing above her front porch.

“When the roses are in bloom, people stop and take pictures,” Peterson says proudly. “If I’m outside, they tell me how beautiful the garden is and how much they enjoy seeing it.”

An anonymous passer-by once dropped off a pack of note cards with a picture of the house on the front.

“I think it’s a testament to the fact that the community around here is very thoughtful,” he says. “It’s a great place to live.”

Fifteen years a Piedmonter, Peterson still looks the part of Manhattanite with his oval glasses, shock of Warhol-white hair, low-cut Chuck Taylor sneakers, and jeans, henleys and hoodies in every conceivable shade of black.

Recently, he walked into a Greensboro furniture store.

“You must be from New York,” a saleswoman said.

How Peterson landed in Greensboro is as interesting as the transformation of his cottage from weary to whimsical.

He recounts some of his earliest memories as a child growing up outside Cleveland, Ohio, in the 1950s and ’60s. His father took the family for Sunday drives through swanky Shaker Heights, where the captains of shipping, steel and banking lived in grand homes.

Peterson wondered what life was like behind those walls.

His life was modest by comparison. His father owned a gas station. His mother was a housewife. His maternal grandfather, a Hungarian immigrant, tended a flower-and-vegetable garden behind the house that the two families shared.

Peterson was about 8 when his family moved to their own home, but he never forgot the flowers, partly because his grandfather incubated cuttings under Mason jars and literally passed on the beauty to the next generation.

When Peterson was 16, he went to work for a florist in Shaker Heights.

He accompanied the shop’s owner to the homes of wealthy clients to gather pretty vases, take them to the shop, fill them with botanicals and deliver them back to their stately homes. Peterson had found a way into the mansions that wowed him as a kid, and he liked what he saw.

“I drove my family crazy because all of a sudden I wanted Waterford and Baccarat crystal and sterling silver,” he says.

Soon, Peterson was arranging flowers.

Acting on the encouragement of a life partner who was a hairdresser, Peterson diverted his flair for composition into beauty school, where he learned how to snip, color and texture hair. He and his partner opened several salons in Cleveland.

“We were extremely successful,” Peterson says.

The couple moved to New York City in the late ’80s after Peterson snared a job with the late Kenneth Battelle, aka Mr. Kenneth, the darling of New York society women who wanted the cachet of being shorn by the man who is often described as the first celebrity hairdresser.

Mr. Kenneth created Jackie Kennedy’s iconic bouffant. Marilyn Monroe, Brooke Astor, Audrey Hepburn, Babe Paley, Katherine Graham, Nancy Kissinger, Joan Rivers and other notable noggins sat in his chair — but only for a cut.

Mr. Kenneth passed his wet-headed clients to his employees for styling. Peterson dried, combed, teased and lacquered his way into a loyal following.

He styled and schmoozed with Pamela Harriman, who was once married to Rudolph Churchill, the son of Sir Winston. Two husbands later, she was hitched to Averell Harriman, the U.S. Secretary of Commerce under President Harry Truman.

Peterson groomed the heads of many women affixed to heads of state.

When First Lady Betty Ford was in town, Peterson did her ’do. She told him about an Italian restaurant that she and the President liked. Peterson said that he’d love to take a friend there.

Ford made a reservation for them. When dessert was finished, Peterson called for the check. He was told that the dinner was compliments of Betty and Jerry Ford.

When the Crown Princess of Sweden was in New York and needed her hair styled, Peterson reported to her suite at the Waldorf Astoria; Mr. Kenneth’s salon was inside the hotel.

At the suite, Peterson was greeted by a man who led him to a room where he could work. Peterson directed the man to move some furniture so that the princess could sit in the best light.

After the princess was coiffed, her father walked into the room, and it dawned on Peterson who had helped him.

“I had the King of Sweden moving furniture around for me,” he says, dissolving into laughter.

With Mr. Kenneth’s blessing, Peterson worked part-time as a personal hairdresser to the CEO of two apparel companies. He traveled the world on her private jet.

“I was feeling all big-shot-like,” says Peterson. “It was a shock the first time I had to fly coach.” Except for a year-long stint with a salon in Palm Beach, Fla., Peterson camped in New York. He and his partner lived in an Upper West Side apartment overlooking Central Park, in the same building where actors Al Pacino and Andie MacDowell lived.

But, after a while, Peterson says, the magnets of love and work in the big city lost their pull. He started looking for a place to move solo. Someplace green, where he could have a yard. Someplace like his boyhood home, only warmer.

It just so happened that a friend, another New York stylist, flew to Greensboro every six weeks to style the hair of a local socialite he’d met in the Big Apple. Soon, he was doing the hair of several of her Greensboro friends. Peterson tagged along to help on one of those trips. During the visit, Peterson and his friend attended a drag bingo event in downtown Greensboro.

“The majority of the audience was straight people, and everyone was having a good time,” Peterson says. “It told me that this place was open and accepting. I thought, I could easily live here.”

A few phone calls later, he had a job at an upscale salon on North Eugene Street. He rented a room on Summit Avenue, watched way too much HGTV and set his sights on restoring an older home.

“I can’t tell you how many power tools I bought,” he says.

He haunted salvage stores, demo sites and antique shops, squirreling away hardscape for his someday yard: a wrought iron arch, a double metal gate, a white picket fence.

One day, as he walked down North Eugene, an aging swan caught his eye.

The sign out front said, “For Sale or Rent.”

Peterson rented with an option to buy. Then he opened his wallet.

He had the hardwood floors refinished and stained dark before he moved in.

Later, with deed in hand, he shelled out for a new roof, water heater, HVAC system and basement waterproofing.

The financial hits kept coming.

Inside the cottage, wood paneling peeled away from the walls. Under that, the original plaster flaked away. And under that, a brick wall crumbled. It was one of two side-by-side brick walls separated by a gap, an energy-saving style known as cavity construction, common in 1924, the year house was built.

Peterson had the inner brick wall repointed, hung with drywall and painted bright white.

He added floor-to-ceiling windows in the sunroom, where he often watches TV with his Labrador retriever, Sammy,

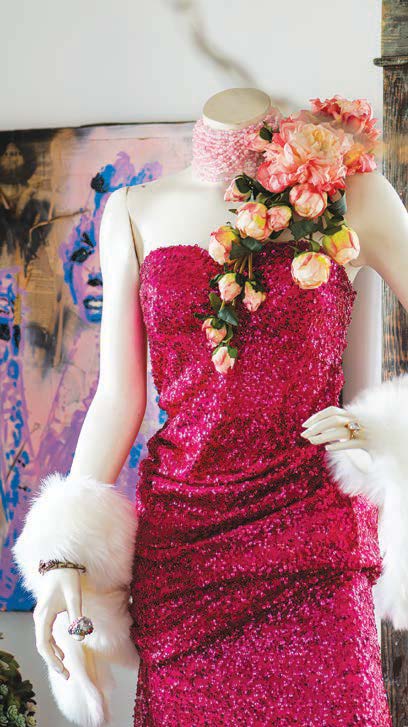

Waves of sunset and emerald tones — in the form of houseplants, artwork and punchy artifacts — carry the eye throughout the house. See a mannequin sheathed in pink sequins in the front room; a large metal pig in front of a Louis XVI repro desk in the middle room; and flying pigs perched in the sunroom.

The glee continues in the backyard with curvaceous rose-colored balusters around porches — including a small wedge that Peterson calls his “Juliet Balcony” — fan-back garden chairs and faux flamingos.

The blushing accents pop against vivid green islands of artificial turf, which Peterson installed so his dog could go outside without stamping the house with muddy paw prints.

The rest of the backyard resembles a wooded hallway. With help, Peterson sculpted fieldstone paths and planting beds down the length. He decked the hall with river birches, azaleas, ligustrum, distylium and ferns.

The walkway ends with a project in progress, an empty landscape-block pond that Peterson envisions catching a tumbling waterfall.

“My wish is to be in a forest,” he says.

For the front yard, his wish is to be in the Cotswolds.

The metal gate, which he found at the now-shuttered Mary’s Antiques soon after moving here, is flanked by concrete orbs given to him by a client. She imported the balls from England.

“I can’t imagine what it cost to ship them,” Peterson says.

He added salvaged porch railings, balusters and a swing.

“No Southern porch is complete without a swing,” he says.

He filled the slatted seat with faux pillows and a throw that he made with spray foam, chicken wire, concrete slurry and paint. He spiked the arrangement with a gazing ball and contained the arrangement with a chain. The spectacle was made for eyes, not fannies.

Ditto the garden tucked between hedge and porch. In season, the space bubbles with a fountain that provides mood music for ferns, roses, azaleas, Asiatic jasmine, coleus, zinnias, impatiens, verbena and whatever else strikes Peterson’s fancy.

He bought a small pickup truck after moving to Greensboro, and he finds it difficult to pass a nursery without loading the bed with more plants.

“I was better off when I had a car, and not a truck, because now I’m not restricted,” he says.

He makes no apologies for his devotion to natural beauty, though.

“If you look at a flower — the color, the shape, the fragrance, everything — it’s a miracle,” he says.

He lets his observation hang before seeking a response.

“Isn’t it?” he finally asks.

The voice belongs not to a jaded urbanite, but to an awestruck kid.