The artful life of Bill Crowder and Joe Hoesl

By Nancy Oakley • Photographs by Amy Freeman

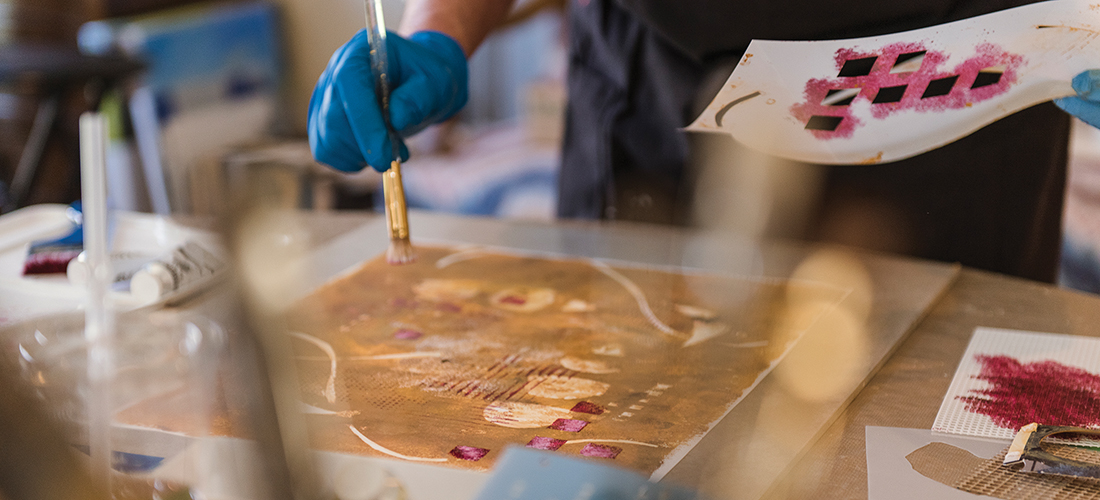

On a bright sunny morning, Bill Crowder, wearing a black apron over his sweater vest and khakis, sits at his dining room table intently dabbing at a palette of paints. Today he is mixing a range of dark blues and purples. “See? I write down the colors I want to use,” he says, picking up his latest work in progress, an abstract watercolor rendered on plasticized paper called Yupo that will hang in an exhibit at The Gallery at The View on Elm downtown. “That way, I don’t have to guess or recreate the color combinations,” Crowder explains. He has chosen the combinations by referring to a color wheel in a sketchbooks that sits atop one of the stacks of books, canvases and plastic trays filled with paints on the long table. “I can always adjust the color, if I need to,” he says, as he manipulates the paint so that a splash of purple takes on a greenish hue.

On a bright sunny morning, Bill Crowder, wearing a black apron over his sweater vest and khakis, sits at his dining room table intently dabbing at a palette of paints. Today he is mixing a range of dark blues and purples. “See? I write down the colors I want to use,” he says, picking up his latest work in progress, an abstract watercolor rendered on plasticized paper called Yupo that will hang in an exhibit at The Gallery at The View on Elm downtown. “That way, I don’t have to guess or recreate the color combinations,” Crowder explains. He has chosen the combinations by referring to a color wheel in a sketchbooks that sits atop one of the stacks of books, canvases and plastic trays filled with paints on the long table. “I can always adjust the color, if I need to,” he says, as he manipulates the paint so that a splash of purple takes on a greenish hue.

From the adjacent room, Crowder’s husband, playwright Joe Hoesl, sits in a chair upholstered in gold fabric — Crowder’s chair — reading. He doesn’t seem to mind that the dining room, where the two frequently entertain — most recently at their annual New Year’s Eve dinner party — has been converted to an artist’s studio. “When you’re constantly surrounded by frames . . .” he trails off, chuckling, before his attention is diverted to the north-facing windows of the dining room where Crowder is working.

“Look at that cardinal!” Hoesl exclaims, as a flash of red hovers by the bird feeder hanging over a bed of daffodils that he’s planted. Just beyond, a fork of Buffalo Creek meanders through woods; all of it, protected wetlands.

“I’m trying to get Joe to go to the other side of the creek bank and plant daffodils,” says Crowder. “He refuses to go through it.” No need. A few buttery yellow blossoms have appeared on their own among the dense thicket of hardwoods.

For about 10 years, the two men have made a home in this corner of Greensboro, where Old and New Irving Park converge, in a townhouse that Crowder redesigned. An artist by training and interior decorator by trade, Crowder works under the handle Crowder Designs, a business he owns with Hoesl and his brother, Gene, who heads up the company’s drapery hardware division. Crowder had been working with two separate clients, each of whom were living in the small brick complex off Cone Boulevard, when he learned that another unit would be going up. “So I spoke to Joe and I said, ‘Joe, they haven’t broken ground yet. It’s the ideal thing, we have all these woods,’” Crowder recalls. Most attractive was the east-facing façade capturing rays of sunlight into the breakfast nook of the tidy kitchen. “We love having morning sun,” Crowder explains. “And so then I took the plans and radically changed the whole floor plan,” he says.

The result is a compact, yet spacious abode and monument to the art, friendships, travel and celebration of life of its two inhabitants. Though only two floors, one could say that it is a multi-story house, because every nook and cranny in it has, well, a story to tell, starting quite literally from the ground floor.

The floor level as originally designed had to be dropped to accommodate the thick buff-colored travertine flooring. And that, too, has a story. “I hemmed and hawed over that travertine,” Crowder recalls. Then he asked his supplier how much it would cost. “$7,000” came the answer. It seemed reasonable enough, so Crowder took the plunge. And then: “How much to install it?,” he remembers inquiring. Answer: “$20,000!” His mouth falls agape as he recounts the anecdote, which underscores the challenge of a decorator creating his own living space. “[It’s] a lot harder than doing somebody else’s house,” Crowder affirms. You’re so afraid you’ll wish you had done that. Why didn’t I put that fabric on the sofa? Because, I’ll tell people, if they don’t like the fabric, it can be recovered. But I don’t want to have to recover it!” He laughs at himself and says, 10 years on, he doesn’t regret the decision to use the travertine.

Its neutral tones complement those in the kitchen, which Crowder extended by about 5 feet when he redrew the townhouse’s plans. With the exception of the glass backsplash, he insisted on real bead board for the walls, keeping its natural grain, knotholes, nail heads and all, by covering it with a light white wash. Crowder points out the Dutch, amethyst tile used as a tabletop for the end table beneath the sunny window of the breakfast nook, and the pedestal base of the dining table that an Italian cabinetmaker fashioned for him. He is particularly proud of the open-sided island, made from two antique doors that he bought from longtime antiques importer Caroline Faison, one of which forms the length of the island; the other one was cut in half to form its ends. “And then he made a top for it,” Crowder says, referring to Steve Spraggs, who, added a countertop approximating the color of the rest of the piece. He points to the chandelier, noting that he barely cleaned it up, leaving its peeling paint that gives the fixture a distressed look contrasting with crystal prisms that Crowder hung from it later.

He acquired the chandelier from an antiques shop in New York that was going out of business in the 1980s, along with many others on Gotham’s Third Avenue, to make room for a new high-rise being built by an up-and-coming real estate tycoon by the name of Trump. “He bought out the different shop owners, but added an incentive that if they would get out earlier, he’d give them a bonus,” Crowder says, explaining that he had been buying chandeliers from the one particular dealer for years. “He said, ‘Why don’t you buy the whole thing?’ And we said, ‘OK!’” Crowder remembers. He estimates it took about 17 truckloads to haul the shop’s contents from Third Avenue to a warehouse in North Carolina, where Crowder and Hoesl moved in 1982.

For Crowder, it was a homecoming. He had graduated from Greensboro College in 1969 with an art degree and, after teaching for a year, moved to Washington, D.C., where he gravitated toward interior decorating. While working at a showroom, he took the advice of a decorator: “If you’re serious about this, you need to go to New York.” Heeding his mentor’s advice, he landed in the Big Apple, where he met Hoesl. “We were in New York for 10 years,” says Crowder. “But I still had a lot of business up there for about 15 years. In fact, we had an apartment there.”

It was the red clay of North Carolina, however, that would prove more fertile for putting down roots: Hoesl is active on Weatherspoon Art Museum’s board and Crowder serves on the altar guild at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church. And of course, the Gate City and surrounding environs have nourished their artistic talents. In 1987, Hoesl penned the first 5 by O.Henry series, five O.Henry short stories adapted to the stage for the Greensboro Historical Museum (now Greensboro History Museum). Thirty years later, the shows are still going strong. “Some 300 stories [to choose from]!” Hoesl says, marveling at O.Henry’s output of about two stories per week. “When [director] Barbara [Britton] calls, I just get the boxes out of the attic,” he says with a laugh, “She asks for five — I give her about eight to ten.” Apart from sorting through the material in the kitchen, Hoesl doesn’t typically work from the townhouse.

It is, by and large, an extended canvas for Crowder, who rediscovered his passion for painting about 25 years ago. Ever working on his craft, he has taken classes from the likes of Alexis Lavine, John Beerman and Charlotte artist Andy Braitman.

In the foyer by the front door hang two of Crowder’s abstracts, in mixed media on canvas. One, Images in Denim is a collage incorporating red paint spatters and swatches of denim, which, appeared in an exhibit last fall at Greensboro Cultural Center, 50 Shades of Blue, (two more from the show are stored in the attic alongside the 5 by O.Henry files). Hanging next to it is another collage in neutrals; on closer inspection, one can just make out the texture of corrugated cardboard, a carton for coffee pods, a paper towel, a cocktail napkin and a swath of terry cloth. “I call it LBI and the Statue of Liberty,” Crowder says, recounting a visit to a friend’s house in Long Beach Island, New Jersey. “They all wanted to go to the Statue of Liberty — in August. I said, ‘Bye!’” he continues. That afternoon, in the solitude of the empty beach house, he completed the work. “That was sand,” he says, pointing to a grainy, buff-colored section of the canvas. “I have a little jar that I brought some home in, if I wanted to use it,” he adds.

Water is a consistent theme throughout the house, from the shell-covered mosaic vase in the kitchen to the brightly covered ceramic stoops (sconce-like vessels for holding holy water) in the hallway. Some are antiques, some are reproductions; one, Crowder acquired in Ravenna, Italy. “I like them because they’re small, and they’re so incredibly different, depending on the artist that’s making them,” Crowder says. “And even though they’re full of symbolism, no two are alike.”

And then, of course, there is meandering Buffalo Creek, just outside the dining-room-turned studio, where at one end hangs a painting of a Venetian canal; at the other, draped over the red sofa by the fireplace is a small throw that reads, “Venice Biennale 2003.” One might say the fanciful Italian city is Crowder’s spiritual home. “Venice is my favorite place . . . In. The. Whole. World!” he says, waxing poetic about his first visit there in the mid ’80s: “It was in February, because I was skiing with two friends in the Dolomites, and then we went to Venice. And it was exactly like the movies — it was hazy and gray and mysterious,” he recalls. “I always said, ‘I don’t love being in water, but I love being on water.’” He hasn’t been to the Biennale in a while, owing to the bite that the Great Recession took out of his decorating and drapery hardware business, but the city of canals is never far from his imagination. In the corner of the dining room stands a cupboard of Venetian glass goblets and plates, and in the adjacent living room, where Hoesl is still absorbed with his book, stands a fanciful glass lamp, that looks as though it were plucked from one of Venice’s grand houses. On the far wall, hangs another homage to the city: one of Crowder’s realistic paintings of a bridge and a canal.

The sitting area also demonstrates his reworking of the townhouse’s original concept. In the other units it is typically used as a master suite. For Crowder and Hoesel, the room, covered in Delft-colored floral fabric, (also the handiwork of Steve Spraggs and his father, Charles) is where they relax in the evenings. The two often take dinner at the small glass table while watching TV, cleverly concealed in a massive cupboard, or they sit and read by the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves crammed with art books and Crowder’s shadow box collages. These, he says, were inspired by Surrealist artist Joseph Cornell, one of Crowder’s artistic influences from his college days. Crowder removes a volume containing Cornell’s works from the shelves and leafs through it. “I’ve had to quit buying books,” he says with a sigh, “because the stacks are beginning.”

And indeed, there are stacks of books scattered about. Many of them are about his beloved Venice, others about artists such as another idol, American painter John Singer Sargent. They fill credenzas, end tables, the night table on the master bedroom upstairs. Originally slated as a bonus room, Crowder’s design raised the ceiling, bringing in more eastern light through two alcoves . . . convenient storage space for his canvases. Like the downstairs, the room is also filled with objects and paintings, each with a fascinating provenance: the wooden triptych with beaded egg sculptures protruding from antennae, the work of a friend and artist Michael Haykin who is also responsible for the nearby series of watercolors of birds’ eggs from the collections at the American Museum of Natural History. Eggs were a passing interest of Crowder’s at the time.

Moments of his life unfold in the small office on the other side of the hallway, filled with paintings and photographs — one of a cat peering outside a screen door. “We don’t have any here, but we used to be cat people,” Crowder says, before wandering through the guest bath, where there are more stoops alongside a splendid, painted glass mirror set inside a round frame of blue spikes, emulating sun’s rays. “It’s from Ecuador,” Crowder says, explaining that it was the last of a sample piece from Baker Furniture. Another of his box collages made with wrappers from Ferrer Rocher candy hangs on the wall, and just beneath it, a photograph of a sailboat from a vacation to the Greek Isles. He remembers sailing in the early morning “to some island that was probably uninhabited. Then we’d get off and have a picnic, swim or whatever. Then we’d sail off and get off at a port and go eat dinner at one of the restaurants,” Crowder reminisces.

Echoes of Greece recur in another striking painting in the hallway: A portrait of the late Andreas Nomikos, painter, set designer, UNCG faculty member and close friend whom Crowder met through a mutual friend, Frances Loewenstein (wife of Modernist architect Ed Loewenstein). It was done when he was a young man of 30. “He turned 30 in 1947, the year I was born,” Crowder reflects. More artifacts from Nomikos’s life fill a curio cabinet in the guest bedroom: worry beads from his childhood in Greece, old black-and-white photographs.

Alongside them in the curio cabinet are blue face jugs from Seagrove. “Joe went through a period where he thought they would be cool because he thought they would make him rich,” Crowder recalls with a laugh. In the far corner of the room is a shrine to 5 by O.Henry, a collage of clippings and playbills. It sits just beyond a glass table that Crowder decorated with a floral motif in decoupage. Resting on top of it are glass containers filled with seashells and matchbooks. “I don’t want to get rid of them, because so many of the places are gone,” Crowder muses. “Bistro Sofia, remember that? The Port Land Grille down in Wilmington. This one’s from Prague. A friend of mine says, ‘Oh I’ve got to bring you something.’ And I say, ‘Do not bring me any more materials!’” He pauses and laughs. “I’ve got too many boxes full of materials.”

The garage downstairs bears him out. For here are shelves full of stuff: paints, and paint brushes, a box of poker chips, shopping bags. On the opposite wall are two more collages, one in brilliant red and yellow, bearing a design made with stencils from coffee pods, another using cartons from San Pellegrino and Perrier water; both will appear in the show at The View on Elm. “This is where I start flinging paint,” Crowder says, gesturing toward an easel where another collage rests. Among the shades of purple and gold is the ribbing from the neckline of an old T-shirt affixed to the canvas with modeling paste. “I was trying to see if I could make Joe park outside, and then I could have this whole half of the garage,” Crowder jokes.

At the very least, he’ll open the garage doors and paint out there with longer and warmer days approaching. Come fall, Hoesl will dig around in the attic again for material that will serve as the basis for the next production of 5 by O.Henry. He is excited about the series’ move to a new auditorium, currently under construction, at Wellspring. Along the way they’ll see the steady flow of friends in and out, culminating in their annual New Year’s soiree. Next spring will see another profusion of daffodils growing in the side yard and with hope, yet more sprouting along the banks of Buffalo Creek. OH

Nancy Oakley is the senior editor of O.Henry.

On View at The View

The diverse talent of Bill Crowder will be on exhibit at The Gallery at The View on Elm (327 South Elm Street) from April 5th through June. Included in the show are realistic and abstract works in watercolor on Yupo and on watercolor paper, textured collages and acrylic paintings. For more info call (336) 274-1278 or visit theviewonelm.com.