Freedom’s Spring

When Jackie Robinson Came to Greensboro

By Doug Orr

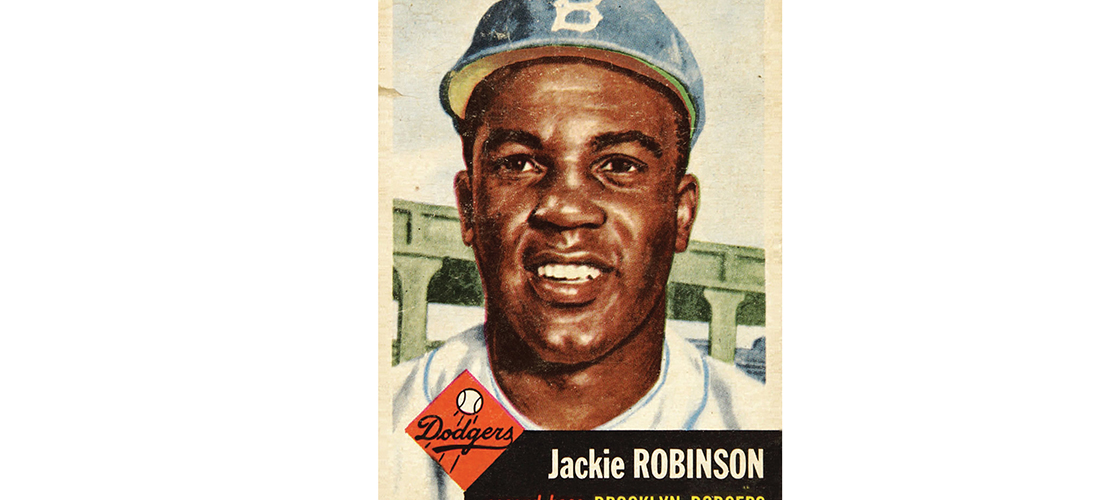

It was on an early spring day, almost 70 years ago, at a baseball game at the old War Memorial Stadium in my hometown of Greensboro that I witnessed early stirrings of the racial liberation of the South. Although Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color barrier in 1947, the following year’s spring exhibition schedule began his first visit to the baseball parks of the region, launching a series of springtime train journeys from the Dodgers’ spring training facility in Vero Beach, Florida, on to New York.

Until then, the South’s African Americans had been deprived of seeing their sports heroes firsthand. The television age was in its infancy. The great heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis never entered the ring south of Washington, D.C., except for a little noticed bout in his career’s twilight days. Robinson had exploded on the American baseball scene and into the national consciousness during that 1947 season, called up from Montreal, and leading the Brooklyn Dodgers to the National League pennant — changing forever the face of baseball and American society. In the process he had become an instant celebrity, as well as a lightning rod for the old passions of racial separation. Nowhere were those feelings more deeply rooted than in the South, and as the Dodgers made their annual springtime railroad odyssey from one Southern city to another, attendance at the parks was overflowing, with the black fans in segregated sections usually making up half the crowd.

It was on April 11, 1950, at War Memorial, home of the Carolina League Patriots, where I had the opportunity, as a youngster, to see this phenomenon unfolding. My father would frequently take me to ball games there and, when the Dodgers rode into town, we were in our usual seats along the third-base line. The crowd of 8,434 was announced as the largest in North Carolina baseball history, and a subsequent newspaper account estimated “another 500 clinging perilously to tree branches and rooftops around the outside of the stadium.” I especially remember the fans seated down the first-base and right-field line — Jackie Robinson’s people — filling to capacity the “Colored Section” of the stadium and dressed as if they had come to church. In a way, they had.

Robinson was playing second base and batting fifth. The excitement in the air was electric as the National League champions had come to our town. But the sense of expectation centered on Jackie Robinson. Even before he came to the on-deck circle for his first at-bat, a steady murmur arose from those segregated seats beyond the Dodger dugout and down the right-field line. Then No. 42 emerged into view, with that characteristic pigeon-toed walk, gracefully taking practice swings. The gathering sound down the right-field stands took on an other-worldly quality, not really as a cheer, but rather a deep-seated stirring, as if a collective human soul was speaking with one voice. It began to spill onto the field in a rising crescendo. Their moment, one that generations before them had longed for, was occurring before their eyes.

Though I don’t recall the outcome of that first at-bat, Robinson went three-for-seven that day, “fielding flawlessly” according to game accounts, and leading the Dodgers to a lopsided 22–0 win over the Patriots as Dodger ace Carl Erskine pitched a one-hitter. But the crowd reaction — that haunting, resonating sound — stayed with me, although as a child in the segregated South, I could not fully comprehend its implications at the time.

In subsequent years, I always pulled hard for Brooklyn’s “Boys of Summer” while most of my school friends rooted for those bitter rivals, the Yankees. A long-awaited world championship came in 1955 against New York in seven games. Yet I never forgot that April day of my youth and the undefinable crowd response when Jackie Robinson first made his way to the plate.

By the 1960s I was grown, graduated from Davidson College, and the nation was awakening to an unfolding civil-rights drama, including, coincidentally enough, the historic sit-ins at Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, now site of the International Civil Rights Museum. There subsequently was the drumbeat of marches, demonstrations, the eloquent cadences of Martin Luther King Jr. and the songs of freedom and social justice. And at that moment, I fully understood what I had heard years earlier during that day at the ballpark in Greensboro. The words to an iconic 1960s spiritual helped bring understanding: “It’s the sound of freedom calling, ringing up to the sky. It’s the sound of the old ways falling, you can hear it if you try.”

As an impressionable youngster, witnessing baseball’s annual panorama in a minor league park that warm spring day with my dad, the deep-throated wail we heard was no less than freedom’s song, whose refrain extended as far back as the slave ships from West Africa. And its torchbearer, passing through the ball parks of our Southern towns, was No. 42, playing second base for the Brooklyn Dodgers. OH

Doug Orr grew up in Greensboro, attended Greensboro Grimsley High School and served as president of Warren Wilson College from 1991–2006. He is co- author of The North Carolina Atlas: Portrait for a New Century; and, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia — both publications of the UNC Press.