Hidden Figure

How a Black washerwoman helped free 15 slaves

By Ross Howell Jr.

Photograph by Bert VanderVeen

Lavina Curry.

We don’t know where “Vina” was born or how she died. We have no likeness of her — no etching or drawing.

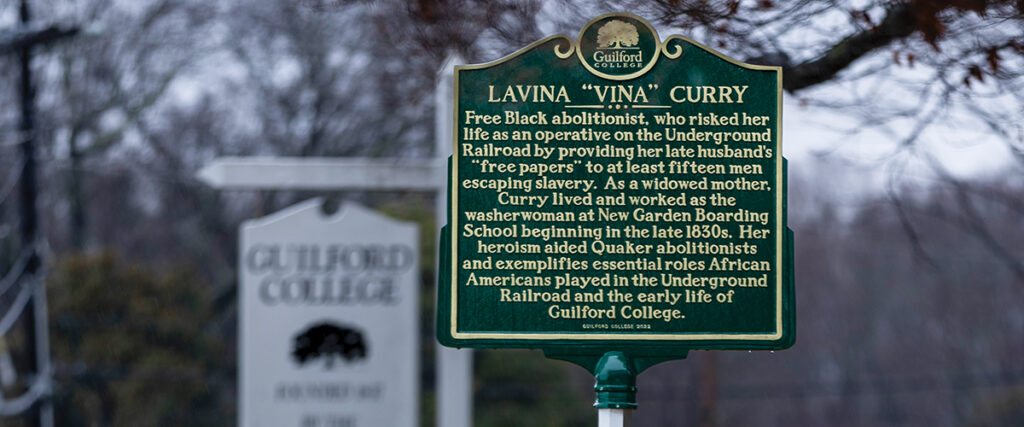

Yet a Guilford College historical marker honors what she did.

Professor emerita Adrienne Israel played an essential role in preserving and telling Vina’s story.

Israel retired from Guilford in 2019, after teaching history there for 37 years. One of her most popular courses was a study of the Quaker community, the local free Black population and the roles individuals played in helping slaves escape North Carolina via the Underground Railroad.

And one of those individuals was Levi Coffin, a Quaker abolitionist born on a Guilford County farm in 1798. His family moved to Indiana in 1826 to avoid persecution for their antislavery views. Historians estimate that Coffin assisted in the escapes of more than 3,000 fugitive slaves during his lifetime.

“Most of the stories about the Underground Railroad were framed around white abolitionists,” Israel says.

“But I was convinced that free Black people in the Greensboro area must’ve been involved, too,” she adds.

Evidence was hard to come by.

Then Israel found a memoir written by a cousin of Levi Coffin, published in 1897.

“There was a free negro named Arch Curry, living near our home, who died a few years after father,” wrote Addison Coffin, whose father died in 1826.

“His widow’s name was Vina; she was the washerwoman for the boarding-school for several years,” Coffin continues. He describes Vina as a “shrewd and discerning” woman who had kept “her husband’s free papers” on hand after his death.

The “boarding-school” was the New Garden Boarding School, predecessor to Guilford College. “Free papers” were documents drawn up by county courts to certify a Black man was a freeman and not a slave.

Vina allowed individual fugitive slaves to use Arch’s papers as identification.

“This was done 15 times to my knowledge,” Coffin writes. He explains that after the fugitive reached freedom, Levi would return the “stolen” papers to the widow.

“This was done occasionally with other papers,” Coffin concludes, “but none were ever used like those of Arch Curry.”

There it was.

A local free Black person helping the Underground Railroad — if Israel could prove “Arch” and “Vina” existed.

Women were rarely named in early records, so Israel started searching for Arch.

Deed books showed that in 1820 a Black freeman named Archibald Curry had purchased land on Brushy Creek in Guilford County, and, a year later, more land on Horsepen Creek. Between the 1820 and 1830 censuses, Curry’s household grew from himself, his wife and two children to seven children — four male and three female.

His name doesn’t appear in the 1840 census, so apparently Arch died about the time Coffin had noted in his memoir.

And Arch’s widow?

The 1840 census counted three female “free colored persons” at New Garden Boarding School.

Among the women was washerwoman Vina Curry, age 55.

Assisting Israel in confirming Vina’s identity was Quaker archivist and special collections librarian Gwen Erickson, who located entries in the school’s ledger for “Lavina Curry.” No entries for Lavina are found after 1843.

It was Erickson who secured funding for the historic marker, dedicated in 2022 as part of a national consortium of universities studying slavery. Erickson says the marker reminds us that there were more free Black citizens who worked with the Underground Railroad and “continue to go unnamed.”

It was up to Sarah Thuesen, associate professor of history at Guilford, to involve students with the project, working with classes to draft the text inscribed on the historical marker.

Thuesen says that while her students had some idea about the school’s role in the Underground Railroad, “they probably never would’ve heard the name of Lavina Curry if not for this effort to recognize all freedom fighters, white and Black.”

And retired professor Israel?

She’s on the trail of one of Vina’s daughters.

“Her name is Sarah,” Israel says. “She moved to Indiana with her husband, a free Black man named Richard Ladd, who had been accused of helping a fugitive slave.”

There’s pride and delight in the professor’s voice. OH

Ross Howell Jr. is a contributing writer.