IT WAS A MALL WORLD AFTER ALL

It Was a Mall World After All

Travel back to long before online commerce was conceived

By Billy Ingram

In 1987, the debut album and single by 15-year-old pop star Tiffany hit No.1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, making her the youngest artist to do so. What was truly remarkable was how she accomplished this feat. Industry insiders credited her performing in shopping malls around the country, the de facto town square of just about every city in America.

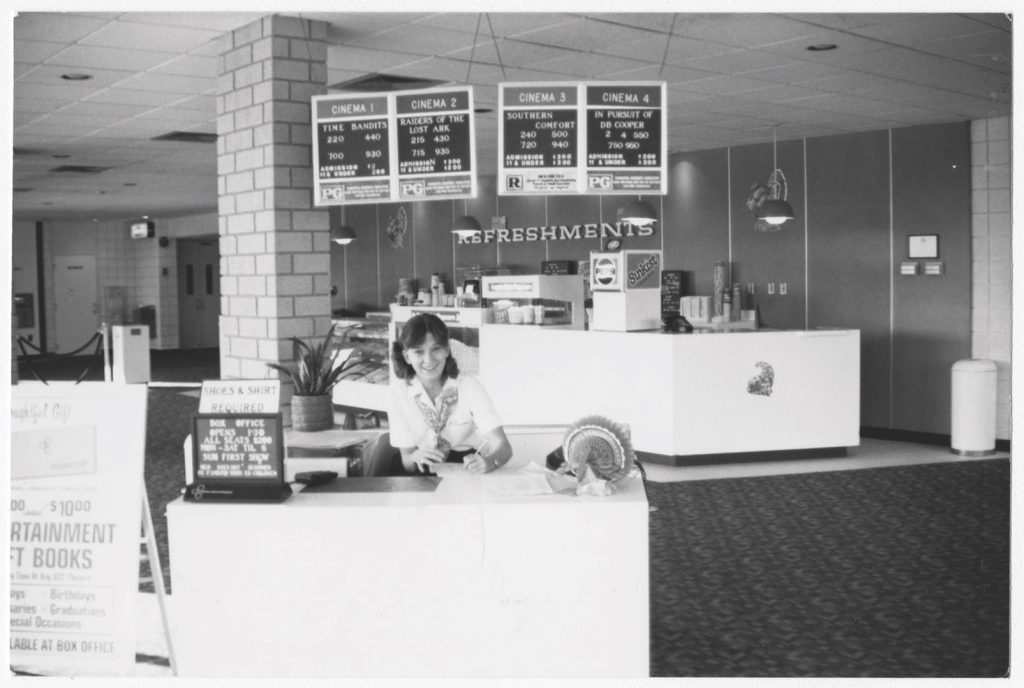

No nearly-forgotten phenomenon exemplified the halcyon days of the ’80s and ’90s like shopping malls. Those cavernous cauldrons of commercialism bubbled over in abundance, thanks to a booming economy and a populous stricken with consumption-itis. When primetime soaps like Dallas and Dynasty demonstrated that “Greed is Good” and those who die “with the most toys win,” malls were where you showed up to show out. So ingrained in daily life, you could purchase a ticket at a mall cineplex to watch a movie taking place in a shopping mall.

Greensboro’s first shopping mall was more than a decade in the making, dating back to 1961 when real estate speculator Joseph Koury publicly broke ground on a game-changing commercial and residential development with a staggering adjusted-for-inflation price tag of half a billion dollars.

For the magnum opus, to compliment his newly-created collage of cul-de-sacs known as the Pinecroft neighborhood, Koury engaged Leif Valand, modernist architect behind Cameron Village in Winston-Salem and Swann Middle School (then Charles B. Aycock Junior High) in Greensboro, to design a 1,000,000-square-foot retail complex housing 95 businesses, to be anchored by three of the city’s most prestigious department stores: Belk, Thalhimers and Meyer’s, rebranded as Jordan Marsh. He called it Four Seasons Mall.

The city’s first climate-controlled shopping mall was an immediate success, with glass and reflective surfaces abounding, gleaming escalators transporting customers standing practically toe-to-toe to a heavenly multitude of unfamiliar storefronts. Each step forward illuminated by a veritable Oz of vibrant logos, wondrous epicenters of excess exuding themselves in every direction, with laminated bricks circling central gathering spaces festooned with flourishing foliage, a brash but bewitching work of architectural wizardry this reimagining of Main Street USA was.

In addition to long-established local merchants such as Prago-Guyes, Schiffman’s and Saslow’s Jewelers, Four Seasons assembled an impressive collection of national and regional clothing and accessories merchandisers, peddling wares almost exclusively influenced by what New York City fashionistas were cat-walking that year.

Catering to the ladies were Lerner Shops (stylish but affordable), Joseph R. Harris Co. (understated sophistication), Hofheimer’s shoes, Lillie Rubin (cocktail attire), Miller & Rhoads (high fashion out of Richmond, Va.), and Thom McAn (footwear). For the junior miss, Deb Shops, 5-7-9, Kaleidoscope, Brooks Fashions and Robins, catering to the pleated-skirt and high-waisted-slacks set. For men’s attire, there was National Shirt Shop (in business downtown since 1932), Mitchell Tuxedo, Frankenberger’s (with a Charleston flair) and The Hub.

Stylish jeans and westerns shirts were stocked at Chess King, The Ranch, Just Pants and Wrangler’s Roost. Headquartered in Charlotte, Wrangler’s Roost had no apparent relationship to the Wrangler corporation, which might explain why they weren’t around for very long.

Four Seasons shoppers stopped for a quick nosh at Chick-fil-A for their new 99-cent, saucy, pulled Chick-n-Q sandwich or Piccadilly Cafeteria. But the unparalleled Mr. Dunderbak’s Old World Market and Cafe served bottled Meister Bräu lager to wash down Deutschland reubens and kraut n’wursts. This was Cherry Hill, N.J.,’s idea of a Bavarian Beerhaus ― the Sopranos would have loved it there.

Record Bar proved to be Greensboro’s premier vinyl purveyor until Peaches Records opened a few years later farther down High Point Road. Paying for your purchases wherever you shopped generally meant having cash on hand. While Bank of America issued the first nationally accepted, general use charge cards in 1958, paying with plastic didn’t actually enter the mainstream before the early-1970s. One reason is that, without a male cosigner, women were ineligible to apply for any line of credit until 1974, which, coincidentally or not, coincided with the proliferation of shopping malls.

Accepting credit cards was time-consuming. Once handed over to the clerk, the card had to be cross-referenced against a weekly-updated booklet of stolen account numbers before a receipt, three carbon copies attached, was filled out by the salesperson detailing the item purchased and amount due. The clerk then retrieved the “Knuckle Buster” stored under the counter and stuck it on the surface with suction cups attached to the base, which secured the several pound device. After slotting the customer’s BankAmericard into the mechanism, sales slip positioned on top, shop associates shoved a weighted rolling head over them, imprinting the receipt with the raised name and numbers from the card.

Four Seasons’ overwhelming allure prompted Friendly Shopping Center’s owner, Starmount Co., to construct its own enclosed retail complex. Anchored by Montaldo’s and conceived as a more upscale experience, Forum VI emerged in 1976 with 40 storefronts surrounding a distinctly moderne yet cozy courtyard flooded with oversized houseplants, all lit in soothing, golden tones. An elegant jewel box of predominantly local retailers that, for various reasons, never really caught on. Only the restaurants, Japanese steakhouse Kabuto and K&W Cafeteria, were consistently drawing crowds — but at hours not particularly advantageous to the mall’s interior tenants.

Debuting simultaneously was Carolina Circle Mall, by far that Bicentennial summer’s brightest retail star. With a reported $25-million price tag ($142.3 million in today’s dollars), “North Carolina’s Unique Shopping and Entertainment Wonderland” was located on the opposite end of town on what was formerly a 220-acre dairy farm bordering U.S. 29, 16th Street and Cone Boulevard.

As a teenager, I attended the grand opening in August of 1976. I’m kinda like a cat with an urge for exploring every aspect of my environment, but, unlike a cat, I left no scent behind at Carolina Circle. Thanks to its proximity to a nearby sewage treatment plant, a sickening stench was already permeating the air. On warm, breezy afternoons that putridity proved overpowering.

Undeterred, on opening day nearly 4,000 cars jammed the parking lot as UNCG students costumed as Alice in Wonderland characters greeted eager consumers inside. Most impressive was the ’70s futurist Montgomery Ward exterior accented with thousands of individual yellow, orange and red glazed tiles surrounding the entrance.

A disappointing number of outlets migrated over as well as duplicates of Four Seasons’ franchises including Belk, Piccadilly Cafeteria and the ever-present Chick-fil-A. Carolina Circle’s maze-like layout allowed for a more intimate feeling with smoked-glass panels, dark-colored handrails and brown, terrazzo flooring.

While the overall effect was warm and fuzzy, the major attraction for many was the first floor Ice Chalet, Greensboro’s only skating rink. Surrounding that slick surface was a food court consisting of Orange Julius, Chick-fil-A and New York Pizza. Started by two Sicilian-Americans from New Jersey, Charles Sciabbarrasi and Ray Mascali, NYP made so much dough they quickly opened another pie hole on Tate Street. That’s still there while Mascali sells slices and pies at NY Pizza on Battleground.

Saturday Night Fever exploded across movie screens in December ’77, infecting the populace with disco fever. Urgent care for disco fever was The Current Event dance club at Carolina Circle, where underaged teenagers gyrated underneath a disco ball rotating on its axis, sending shards of light across its expansive orange, yellow and black under-lit dance floor and backlit pylon barriers. One lingering feverish side effect? An overwhelming desire for ”wild and crazy guys” to possess that white, polyester, three-piece suit John Travolta wore to seduce the nation — and Karen Lynn Gorney. J. Riggings sold them on the second floor, where they were, like every highly desirable item, literally chained and mini-padlocked to the display rack.

The city’s (possibly the state’s) first skateboard park opened along the eastern end of the parking lot, closest to the sewage plant. Those concrete bowls proved a popular spot for both teenagers and younger kids, despite required knee pads and helmets. That skate park was short-lived, as was the outdoor Hawaiian Surf Water Slide retired pro wrestler John Powers opened in 1978.

The proliferation of easily accessible credit cards in 1980s and ’90s ushered in an era of haute couture from designers Betsey Johnson, Donna Karan, Liz Claiborne, Tommy Hilfiger, Perry Ellis, Guess, Ralph Lauren and my favorite, Ton Sur Ton, found at Express, Gadzooks, Claire’s, Merry-Go-Round and Mervyn’s stores. And unless someone possessed a perfectly pear shaped rear end, no man or woman ever looked right in those impossibly tight Jordache stonewashed jeans.

Sharper Image hawked high-tech gadgets no one knew they needed — computer bridge games, massaging chairs, Truth Seeker vocal stress detectors — with eye-popping price tags. Farrah Fawcett posters, cheap jewelry, infinity mirrors and goofy geegaws were Spencer Gifts’ oeuvre. Would it surprise you that they are behind those invasive pop-up Spirit Halloween shops?

Despite the hype, a requisite steady stream of shoppers never materialized for Carolina Circle. In 1986, the property was offloaded at a loss for $21 million. The new owner pumped an additional third of that investment into major renovations, including a spectacular pink, neon-like facade leading into a significantly brighter interior highlighted by enormous, pastel-colored butterflies, which hovered overhead, along with a new name, The Circle. On re-opening day, a choir resolutely standing center stage belted out the “Hallelujah Chorus,” but the resulting redux proved a resounding flop. Many a heart melted when the Ice Chalet was removed — too expensive they said — in favor of a $250,000 carousel decorated with Greensboro landmarks. The drain circling continued unabated.

Changing hands again for a mere $16 million in 1993, The Circle’s asking price was undoubtedly negatively affected by an incident that happened two years prior. A father, on an outing with his daughters, was gunned down outside of Montgomery Ward. The Greensboro Police Department establishing a satellite station inside the shopping center only served to solidify its seedy reputation.

Imagine my horror upon discovering around that same time that my 70-year-old mother was still frequenting The Circle’s Belk — which was hanging on by a thread, but one of the few retailers left due to rampant gang activity. I implored her to stop, but she liked the salespeople. After that conversation, I accompanied her whenever she shopped there.

Strolling the mall interior as she perused the racks, around a third of the storefronts were darkened caves, even Great American Cookie Company was crumbling. “If a terrorist came in and blew up the mall,” one demoralized merchant groused in 1996, “The headline would read, ‘Mall Blows Up, Nobody Injured.’” Well, there’d be my mom . . .

As a Hail Mary play, The Circle descended into an assemblage of storefront tabernacles alongside a fitness center before its 2006 date with the wrecking ball. Currently the site of a Walmart Superstore, the only physical remnant still standing is Montgomery Wards’ one-time tire-and-auto center on 16th Street.

In 2015, the scant remaining Forum VI retailers were unceremoniously evacuated for transforming the interior into an office complex. Kabuto objected; after almost 40 years, its hibachi hadn’t cooled. Determined to continue, its owners built a stand-alone pagoda on Stanley Street, where they still enjoy a bustling business today. The only remaining holdout at Forum VI is K&W Cafeteria, still serving up the same recipes, its mid-’70s dining-room decor perfectly preserved.

Out of curiosity, on a recent weekday afternoon I ventured out to Four Seasons Towne Centre. Employees outnumbered the zombie-like walkers in attendance, and blank wall installations covered over a depressing array of abandoned storefronts. The escalator wheezed, stuttered and clanked under the weight of my 150-pound frame, the sole passenger on its downward trajectory. Today’s star attraction appears to be the senses-shattering, potentially seizure-inducing bowling alley/arcade located in Jordan Marsh’s (later Ivey’s) voluminous former ground-floor entrance.

I asked friends born in the ‘80s and ’90s about their own mall memories. They didn’t have any. One remarked he had no need for the mall because he already had a girlfriend in high school. Perhaps this impression was because, sometime in the 2000s, the mall experience had devolved into a latchkey kids’ land of the lost, somewhat akin to a primitive dating app like Tinder, a convenient hookup venue where joy seekers simply slid left into Forever 21 when spying someone undesirable.

A pity shopping malls ultimately came to represent in-person purchasing’s very own Alamo, where retail desperados collectively mounted one final assault to squeeze the last possible dollar from antiquated business models they knew were totally unsuitable for the new frontier. Now, they’re a relic of our nation’s overwhelming desire for escaping into fortresses where ease of attainment meant atonement; momentarily, that is, until the creditors came calling.