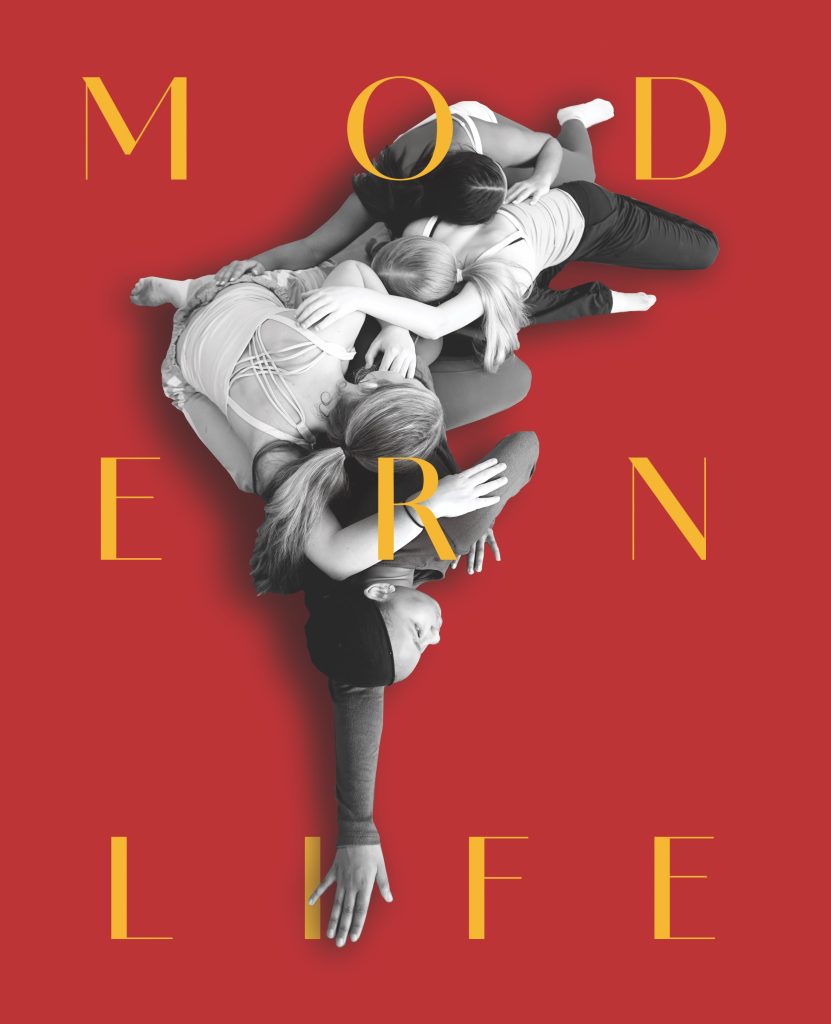

MODERN LIFE

Modern Life

Based in Greensboro, the NC Dance Festival celebrates its 35th anniversary of showcasing the state’s best contemporary dancers

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Lynn Donovan and Brandi Scott

Bathed in fluorescent studio lights and stepping lightly over a cushioned vinyl floor, Jiwon Ha shows her young students how to bolster a fellow dancer who wants to descend gracefully to the ground during a modern piece.

The mechanics are tricky, so Ha, who is remarkably youthful at 40, demonstrates by leaning way over to her right. Dressed head-to-toe in black, she appears as slight and springy as an eyelash.

Her left leg leaves the ground as she reaches the tipping point. She urges her charges to act quickly as gravity does its thing.

“Catch me! Catch me!” she says, hopping on her right foot to stay upright.

Four teenage girls — all students at Dance Project, a Greensboro-based nonprofit devoted to the art of choreographed movement — rush to grab her by the leg, arm and waist.

Suspended in mid-air, Ha uses the moment to teach: Once the counterweight is right, and the stress is balanced, it’s easy to land softly and rebound again. The underlying structure must be right.

It’s a concrete lesson in the importance of support.

The NC Dance Festival gets it.

On October 18, the annual gathering, which is organized by Dance Project, will mark 35 years as the primary showcase for the state’s modern dancers.

The mainstage program for that day will include some of Ha’s students, who’ll appear as a pre-professional group.

On November 7, the young cast will perform again at a special show for students who have been exposed to dance in local elementary, middle and high schools. Both times, the pre-professional dancers will execute a piece created by Ha, which expresses the emotions of adolescence.

“I want to create a dance piece that will connect with the artists and audience members as well,” Ha says. “I’m super-pumped to be a part of the North Carolina Dance Festival.”

Sure, Durham has the American Dance Festival, which pulls from a nationwide pool of talent, but Greensboro’s celebration is distinct because it focuses solely on modern dancers across the state.

That was the vision of the late Jan Van Dyke, who founded Dance Project as a harbor for her own performing company in 1973. Working with university dance programs around the state, Van Dyke launched the festival almost 20 years later, in 1991, with the goal of growing community support for dance.

The festival traveled from campus to campus for several years. Then came a phase of performing at off-campus venues. Since COVID, the festival has centered mostly on the Greensboro Cultural Center’s cavernous Van Dyke Performance Space, a stage named for the festival’s founder, who died of cancer in 2015.

With Dance Project headquartered a couple of floors above, Van Dyke’s spirit still looms large in the cultural center and in the local dance community 10 years after her passing.

A celebration of her life, co-hosted by Dance Project and UNCG’s School of Dance, will be held on September 28 and will include light refreshments, storytelling and videos of Van Dyke’s work. The event would be a good place for the dance-curious to dip a toe into the festival.

“Some people are a little intimidated by dance — maybe they don’t understand it,” says Anne Morris, executive director of Dance Project and the festival. “We try to open the doors to understanding.”

In crafting the mainstage program for next month’s festival, Morris and her board of adjudicators, who reviewed submissions without knowing who the choreographers were, have tried to assemble a varied menu.

“We work really hard to curate a show that’s a pretty good mix of a lot of things,” says Morris, adding that viewers will see elements of hip-hop, ballet, tap and other genres.

Not charmed by the style of an individual piece?

“Stick around,” Morris urges. “You might find something you like.”

The festival lineup includes an appearance by Stewart/Owen Dance, a well-known company in Asheville. They will perform a work that was commissioned by the American Dance Festival.

“It involves fronts, putting on a mask to be what you think society expects of you,” says Morris. “At times, it has a vaudeville feel.”

Other mainstage artists include:

– Alyah Baker, an assistant professor of dance at UNC-Charlotte. Combining dance with feminist activism, she draws on the work of Black poets Nikki Giovanni and Lucille Clifton.

– Eric Mullis, choreographer and co-director of the Goodyear Arts space in Charlotte. The multi-talented Mullis is also a Fulbright Scholar and an associate professor of philosophy at Queens University. Fascinated by motion-capture technology, his performance will include video projections of color and movement.

– Chania Wilson, a native of Clayton and a 2021 graduate of UNCG’s School of Dance, will present an excerpt from her Duke University master’s thesis performance. The six-person work, called There is a Ladder, deals with documenting the experiences of Black women in dance.

The thought of returning to Greensboro brings back fond memories for the 26-year-old Wilson. She remembers visiting the city to attend a high school dance day at UNCG.

“I was blown away when I got here,” she says. “I loved the energy — how the community and faculty and students engaged. I thought it was the ideal college environment.”

As a student at UNCG, Wilson says, she was tried by circumstances. The university’s main dance studios were under renovation during her freshman year and her classes were scattered to other stages.

“I made a lot of memories sprinting across campus,” she says.

COVID arrived during her junior year, forcing her to attend classes via Zoom. She recalls being in her off-campus apartment on Spring Garden Street, putting a batch of banana bread in the oven, setting her laptop on the breakfast bar, joining an online class, and doing a West African dance in a 4-by-4-foot space she’d cleared by moving her couch aside.

“Doing West African dance on Zoom was interesting because of the drumming. Sometimes, there would be a lag, and I was like, ‘I know I’m not on beat, but I’m trying.’ It was definitely an era,” she says, laughing now about the experience.

“I think every generation has an element of, ‘Oh, we had to work through this to make us stronger.’ For me, I realized that I dance for the sake of being around other people and community.”

Jiwon Ha found similar comfort in the Piedmont’s dance community. She and her husband, John Ford, a software developer from Greensboro, moved here from her native South Korea in 2016.

Ha was wary of relocating because of anti-immigrant sentiment expressed by some Americans during the national election year, but dance allowed her to make connections easily.

“I’m so grateful that dance is a universal thing,” she says. “Once we move the body, we are all the same.”

For a while, she struggled with understanding English, especially English soaked in Southern accents.

“Now I say ‘Y’all’ very naturally, and sweet tea is my new drink,” she says. “I’m grateful that I moved here at that time after all.”

As a dance teacher at Elon University, UNC School of the Arts, and Dance Project, Ha is experienced at guiding young students. She taught teenagers at a dance conservatory in South Korea. There, she says, the teacher-student dynamic is hierarchical. Here, she says, the relationship is more egalitarian, with American students being prone to share ideas with teachers.

“They’re more vocal, which I appreciate,” she says. “It’s a newer generation, and I’m very grateful that I can work with them.”

Her rapport with students is evident in the studio, where she steers them with a keen eye while issuing gentle corrections and ample praise.

“Fall.”

“Rise.”

“Softly walking.”

“Reaching out.”

“Latching arms.”

“Eyes sparkling.”

“Good”

“Nice.”

“Beautiful.”

Ha uses the Graham technique, as in the legendary dancer Martha Graham, which emphasizes the contraction and release of spine. Cupping the hands and spiraling with an open, lifted chest are two hallmarks of the technique.

Ha is quick to demonstrate to her students, often dancing beside them. When they veer off course, she nudges them with a light touch to the arm or back. The dancers appreciate her hands-on approach.

“Jiwon is really specific, and I like that because it allows me to work on my technique and choreography while feeling really comfortable,” says 15-year-old Heba Shawgi, a student at The Early College at Guilford.

From dance, she says, she has learned lessons that apply to school and personal relationships as well.

“It’s important to be yourself and realize everybody makes mistakes,” Shawgi continues. “Everybody is going through the same learning process.”

Sitting on the floor, chatting with Ha after their class, the girls share what modern dance has meant to them: a place to build physical strength and skills; a place to find friendship and connection with like-minded people; and a place to grapple with emotions, especially the anxiety that can come from comparing oneself to others, whether in school or in the studio.

“It’s hard not to compare yourself to others,” says Sophie Kohlphenson, 17, a student at Weaver Academy. “You have to constantly remind yourself that you’re not gonna dance like the person next to you. It’s definitely a process I’m still trying to work through.”

The young dancers are quick to offer advice to festival-goers who might not be familiar with modern dance.

“I would just tell them to lean into it,” says Jessica Smith, 14, also a student at Weaver. “You can’t really make much of modern dance if you don’t take it all in.”

Sometimes a dance will provide an obvious story, they say. Other times, the works will be less narrative and more abstract, just as with paintings and other fine art.

“Everyone is going to interpret it differently,” says Sid Dixon, 16, a Grimsley High School student. “Take it how you want it. You don’t have to understand it to watch it.”

Later, Ha expands on their thoughts, providing a few more handholds — or footholds, as the case may be — for new audience members.

“Even if someone doesn’t know much about modern dance, there’s still a lot to enjoy: the physicality; the strength it takes; the emotion in the movement; or simply the satisfaction of watching a group move together as one,” she says.

“There’s also something really beautiful about its in-the-moment nature. It’s here, and then it’s gone, just like life. I hope all audience members can sit back and enjoy without feeling pressure to analyze.”