Prayers and Poetry

To see inward, first look up

By Jim Dodson

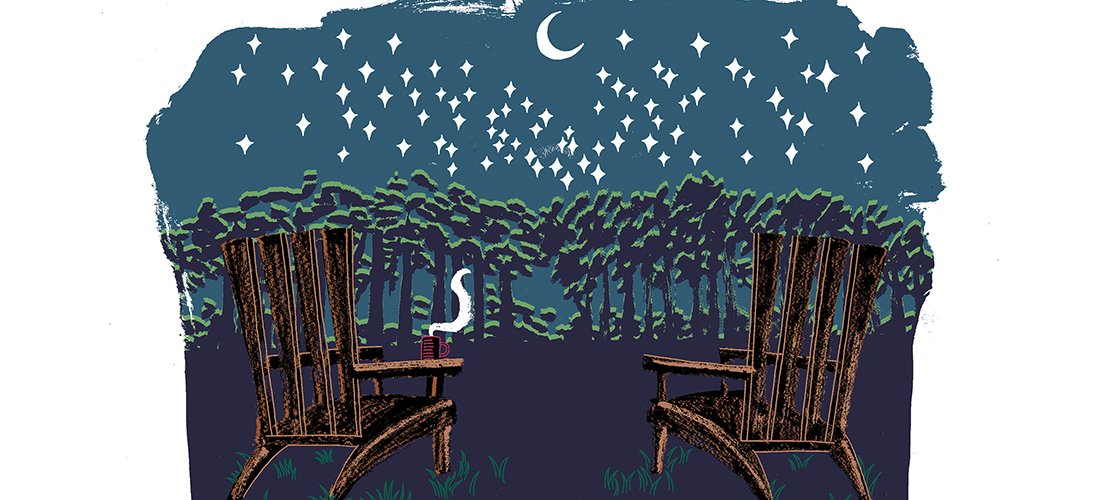

Early one morning not long ago, as I do most days, I took the day’s first cup of Joe out to the front yard to sit for a spell in an old wooden Adirondack chair that provides a wide view of the night sky. Something about its vast clockwork beauty comforts me. My foundling dog, Mulligan, seems to dig our predawn ritual, too.

October and November’s skies, particularly in the hours well before sunrise, are among the clearest of the year, and this particular morning was outstanding, with Venus shining over my left shoulder and a gibbous moon over the right, casting faint shadows on the lawn.

The stillness was deep, the silence broken only by a lone dog barking miles away and the sound of a train grinding over the horizon to its destination.

Such peaceful hours — my version, I suppose, of an ancient matins ritual, a venture into thin spaces — always restore something needed in me, a healing sense of optimism and gratitude. Pieces of my favorite poems and prayers waft through my mind.

The recovering journalist in me, however, understands that the serenity of a glittering firmament is either a gift from God or a grand parlor trick of the universe, merely the latest quiet before the storms of another day on this beautiful blue planet we inhabit.

As I sat there gazing up at the early stars, the largest Atlantic hurricane of modern times was bearing down upon the Florida Straits, a Cat 5 storm with eight million people in its sights. Overnight, an 8.1 earthquake had rocked the coast of Southern Mexico, the largest recorded in that nation in 100 years, killing 96, many in their beds.

This was mere days after a Gulf hurricane transformed Houston into a waterland of death and misery, robbing tens of thousands of their homes. There were also record wildfires burning out West and killer floods across India.

Suddenly I heard the voice of my old Latin teacher, Professor A.

“So, young souls, why are you here?” he asked on the first day of Introduction to Latin and the Classics. This was the Fall of 1971.

A girl spoke up to say she believed Latin was necessary for the law career she hoped to have someday.

Another, aiming for medicine, concurred.

“I heard it was a fun class and I need three credits to graduate,” offered some wiseguy in back. The class laughed.

Around the room it went until it came to me.

Truthfully, a freshman English lit and history major, I was there because I’d opted to sign up for three Latin courses in order to avoid a single course in calculus, what my faculty advisor referred to as the “classical death option.”

“The second book I ever owned was an illustrated book of Greek and Roman Myths,” I said, hoping that would suffice.

Professor A. smiled. “If I may ask, what was your first?”

“The Little Prince,” I replied.

This brought another smile. “Perhaps someday you will be an astronaut.”

Then, a bit of advice. “Anytime you wonder why you’re really here on this Earth, I suggest that you simply look up and let the wonder fill you they way it grounded ancient travelers and sages. The sky makes philosophers of everyone.”

Four autumns later, on my way home to Greensboro to take a job as a rookie reporter at my hometown paper, I dropped by Professor A.’s office to say thank you for opening a larger world to me. Because of him, I’d read Cicero and Ovid and a translated Odyssey and come to love the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. If my grasp of Latin wasn’t the best, though a few bits bubble up from time to time, my understanding of the Roman and Greek minds was like a gift from the gods, something I would take with me — and turn to — throughout my life and career.

Luis Acevez was a dapper little man, a scholarly son of Guadalajara who favored tweed jackets and striped bowties. His bearing was formal, Old World. He stood and offered me his hand, wished me Godspeed with a hint of a bow and that same Socratic smile. “Any time you lose your way or forget why you are here, just look up and the stars will remind you.”

He went to his shelf and pulled out a slim volume, a new Penguin edition of Emperor Aurelius’s famous meditations.

“Salve,” he said, offering the classic Roman greeting which meant Hail and Live Well!

I saw Professor A. only one other time. If I believed in accidents, this might simply have been a happy one. But life has shown me there’s no such thing as accidents.

Many years later, I was briefly visiting the campus to receive an honor for my writing. While killing time at the student bookstore, I spotted him — almost didn’t recognize him without his tweeds and striped ties, not really sure he would remember me.

“Ah,” he said with delight, “the young fellow who didn’t become an astronaut after all.”

I was touched that he remembered me. He’d been retired for more than a decade. I was even more touched when he mentioned that he’d taken great pleasure in following my career as a journalist.

By this point in my still-young working life, I’d written about everything from pointy-headed Klansmen in Alabama to serial killers in Atlanta. I’d covered so many misbehaving politicians and so much violent death and mayhem across my native South, I’d finally been force to flee to a winding green river in Vermont to try to sort out the world and find a measure of inner peace. That’s where I discovered arctic winter nights full of glittering stars and a silence so deep and healing, I heard my own pulse slowing down. That’s where I reread the classics, rediscovered that old copy of the Meditations and started my life anew. My presence on the campus was because of a memoir I’d published about my final travels with a wise and funny father, an adman with a poet’s heart who helped me find the way to a more fulfilling life.

Though I never mentioned his name, Professor A. had played a part in that eventual rebirth and memoir.

So I thanked him again for that new Penguin edition of the Meditations which was still with me, now dog-earred, impossibly marked up and coming apart at the seams.

This seemed to please him.

Since that time, whenever the world itself appeared to be coming apart at the seams, I have turned to poets and Rome’s Philosopher King for useful perspective.

“And anytime I forget why I am here,” I told my old professor, “I simply look up at the stars.” He just smiled.

“Salve,” he said.

“Salve,” I returned the ancient greeting.

This is why I sit beneath the stars most mornings with my coffee and my dog, Mulligan, named for a second chance at life, regardless of season or weather. Even if they aren’t visible, I know the stars are always there.

Often I send up a simple prayer of thanks — the medieval Christian mystic Meister Eckhart says a simple thank-you works wonders — and other times I simply think about poets and philosophers who’ve helped me on my long journey from darkness to light, especially an adman with a poet’s heart and a dapper little professor who found his guidance in the stars.

“Last night,” wrote the poet Wallace Stevens, “I spent an hour in the dark transept of St. Patrick’s Cathedral where I go now and then in my lonely moods. An old argument with me is that the true religious force in the world is not the church but the world itself: the mysterious callings of Nature and our responses.”

Over supper recently, a friend who described her pilgrimage to see the Summer’s eclipse in totality as “a spiritual experience,” remarked that the record hurricane and earthquake were merely Mother Earth explaining that we have become careless stewards of this marvelous blue planet.

I suddenly remembered a passage from the old Emperor that I committed to memory decades ago: “Think of your many years of procrastination; how the gods have repeatedly granted you periods of grace, of which you have taken no advantage. It is time to realize the nature of the universe to which you belong, and of that Controlling Power whose offspring you are; and to understand that your time has a limit to it. Use it, then, to advance your enlightenment.”

Almost on cue for the gods, another old friend at the table who finds his deepest healing in making music with his one of his six guitars, began quoting a Southern troubadour named Walt Wilkins, whose song perfectly explained my mornings beneath the heavens.

I can’t explain a blessed thing

Not a falling star, or a feathered wing

Or how a man in chains has the strength to sing

Just one thing is clear to me

There’s always more than what appears to be

And when the light’s just right

I swear I see poetry OH

Contact Editor Jim Dodson at jim@thepilot.com.