Drinking with Writers

A Born Storyteller

Wills Maxwell makes comedy real

By Wiley Cash • Photographs by Mallory Cash

Wilmington-based comedian Wills Maxwell routinely opens his sets with a joke about what he claims is his desire to fit in. “I’m a conformist,” he says. “I’m such a conformist that the only reason I’m black is because everyone else in my family is.”

The son of an attorney and an insurance claims adjuster, and the brother of three sisters — all of whom have advanced degrees — the career path Wills has taken proves he is not one bit concerned with conformity. Even when he was a kid growing up in Raleigh, Wills knew he wanted to be a storyteller.

“My ambition was to write comic books about superheroes,” he says. “I wanted to tell stories however I could, so I came to UNC Wilmington and studied filmmaking and screenwriting and learned how to tell stories that way.”

The skill Wills developed behind the camera landed him a job directing the morning news at WWAY TV-3, the NBC/CBS/CW affiliate in Wilmington, but it was his talent in front of the camera that landed him a weekly segment he calls “What Did We Miss?” in which he “tells you the stories that WWAY did not.” The three-minute segments cover outlandish news, and they are marked by Wills’ hilarious one-liners and asides. In one episode he covers a crew of car burglars in Los Angeles who are using scooters to flee the scenes of their crimes. In another episode, he covers the story of a man in an Easter bunny suit who breaks up a street fight without removing his mask.

It is no surprise that Wills is able to turn inane news items into comic gold. He has been perfecting his comedic timing and writing for several years, first on stage at Dead Crow Comedy Club in Wilmington, and later on stages across the Southeast. His big break came last year in Charlotte when he made it to the finals round of StandUp NBC, a nationwide search for stand-up comedians from diverse backgrounds. That success got him an invite to return to this year’s Nashville competition and an automatic leapfrog to the second round, where he will have two minutes to earn another spot in the finals.

For Wills, it all comes down to storytelling: “Comedy lets me tell stories in a way that puts people into my perspective, so maybe they can leave the show just a little more aware of how other people live.”

Recently, Wills and I sat down for lunch at the Dixie Grill in downtown Wilmington, and as we ate — a club sandwich for me and a chicken finger basket for him — we discussed his desire for audiences to see things from his perspective. I ask him what that means to him.

“In the summer of 2015, I went to Charleston, South Carolina, to work on an independent film,” he says. “I arrived in town a week after Walter Scott was shot in the back by a police officer while he was running from a traffic stop because he had a broken brake light. Filming wrapped and I left Charleston one week after Dylan Roof murdered nine people just because they were black.”

He pauses and looks out the window at the tourists on the sidewalk, some of them heading north on Market Street toward the city’s Confederate monuments.

“Those were dark bookends to my summer in Charleston,” he says. “Even before those tragedies I was on edge and paranoid, and I was thrown by Charleston’s adoration for the Confederacy. But I found some kind of relief in seeing the Confederate flag being flown because it showed me that I was not welcome everywhere. I did not have to rely on suspicion. It was proof.”

I ask him if it is hard to take these serious issues and make them funny in front of an audience.

“It can be hard,” he says. “The goal is to make people laugh and to make them feel good, but I want things to stick with people in a way that makes them say, ‘Oh, I’ve never thought of it like that.’ After Walter Scott was shot, I made jokes about being afraid of the police. Now, maybe someone in the audience doesn’t have my paranoia about the police, but if they hear my jokes it may make them understand a little about why I feel afraid.”

I comment that all comedy is based on tragedy, either your own or someone else’s.

“And laughing helps us understand it,” Wills adds. “It helps us look at someone else’s tragedy and really see it, but every audience is different.”

Later, this summer, Wills will be returning to Raleigh Supercon, a three-day festival for people who love comic books, science fiction, fantasy and video games. “It’s nice to be in front of a crowd that gets my jokes about the Power Rangers,” he says.

I imagine that it is also nice for him to get away on a weekend instead of pulling late nights in clubs after waking up at 3 a.m. to get to the news station to prepare for that morning’s show. I ask him how he does it, how he works the stage late into the night and works behind the camera early in the morning.

“I feed myself,” he says. “I stay alive. I pursue what I want to do.”

Spoken like a true nonconformist. OH

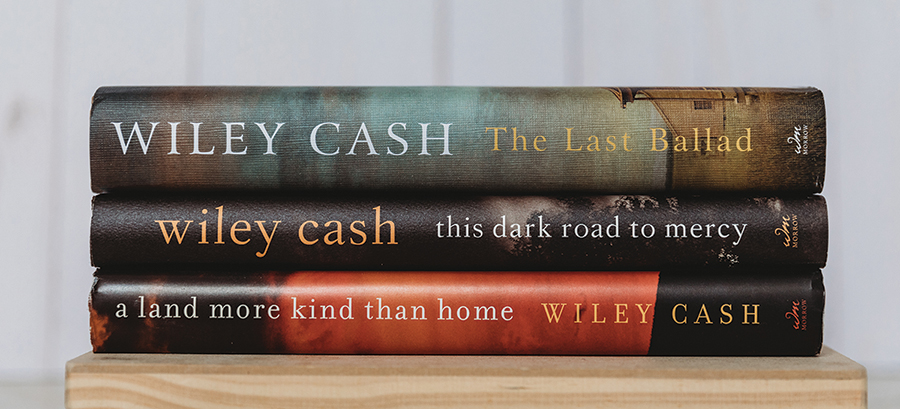

Wiley Cash lives in Wilmington with his wife and their two daughters. His latest novel, The Last Ballad, is available wherever books are sold.