White House Drawing Room

WHITE HOUSE DRAWING ROOM

White House Drawing Room

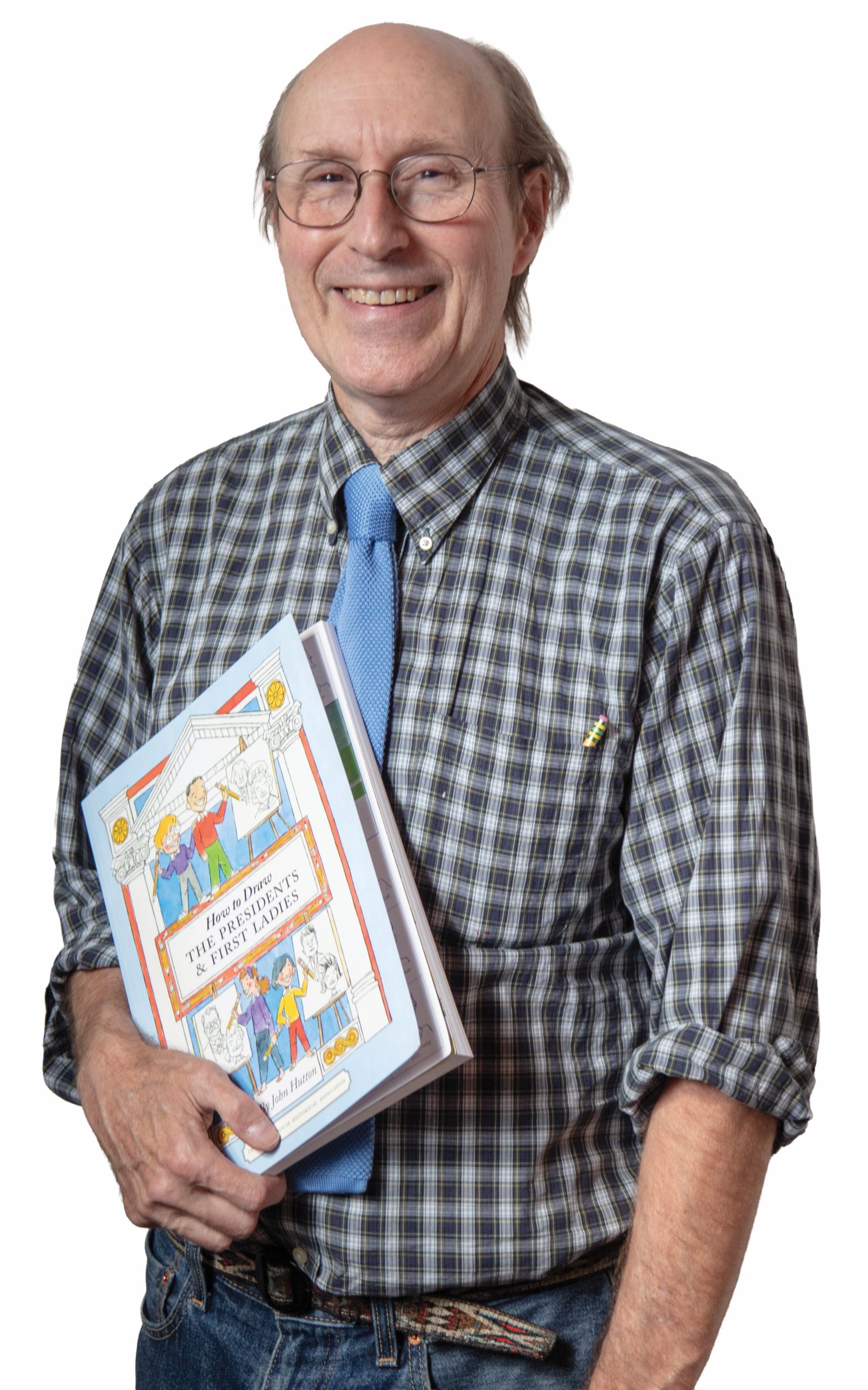

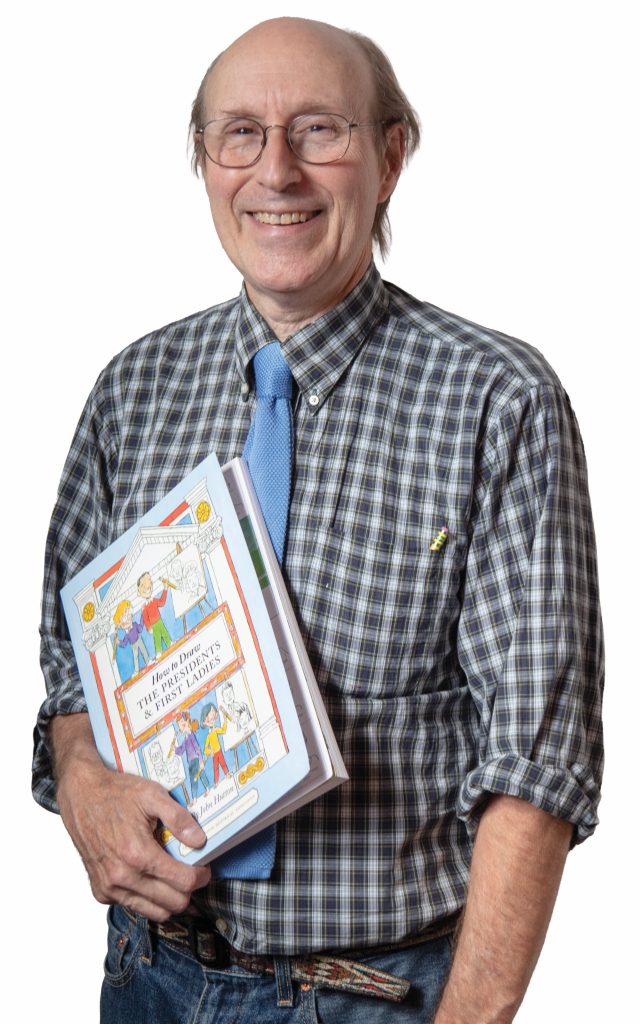

John Hutton says he can teach anyone to draw U.S. presidents and first ladies. We put him to the test.

By Maria Johnson

Photographs by Mark Wagoner

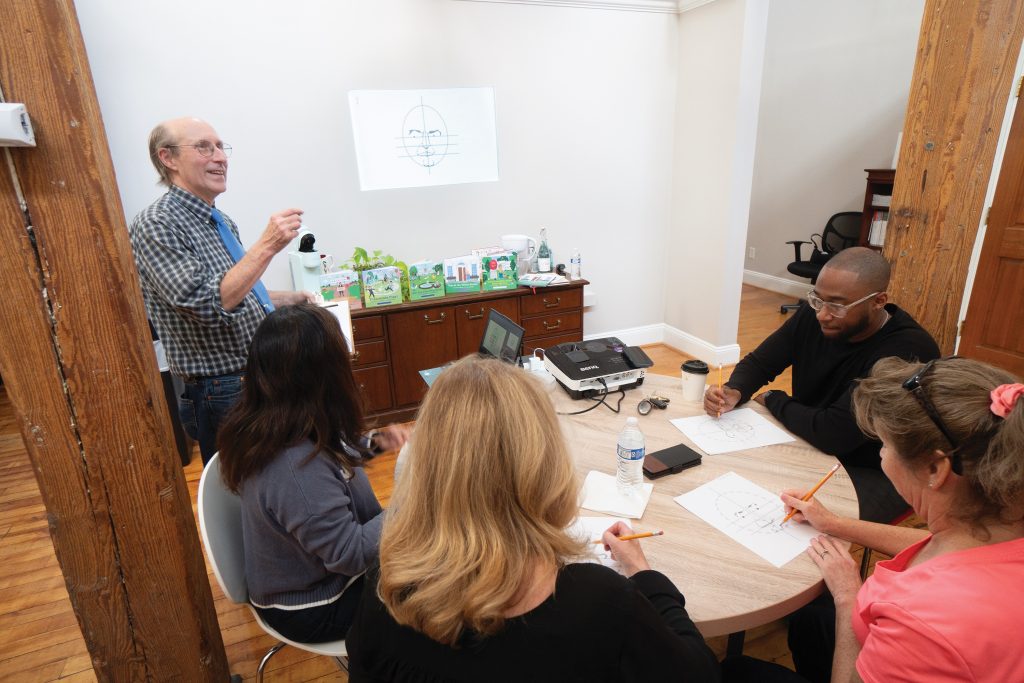

A Friday afternoon.

A few cans of seltzer water.

A half dozen No. 2 pencils.

A projector.

A teacher who knows what he’s doing.

And a half dozen good-humored students.

Welcome to art class, O.Henry style.

Recently, we drafted a sketchy crew, in the best sense, to mosey over to the magazine’s office in Greensboro’s Revolution Mill.

Our recruits accepted the invitation — OK, it was more of a plea sweetened by the promise of snacks — to test the skills of John Hutton, a professor of art history at Salem College in Winton-Salem.

Hutton claims that he can teach anyone to draw a U.S. president or first lady, and he’s willing to put his executive powers on the line, with good reason.

Last year, his book, aptly named How to Draw U.S. Presidents and First Ladies, was published by the White House Historical Association and won the 2025 American Book Fest Book Award for Best Children’s Novelty and Gift Book.

The workbook gives step-by-step instructions for rendering the 45 men who have served as president.

The book also depicts 47 women — most of whom were actually married to a POTUS.

Two presidents — Woodrow Wilson and John Tyler — were widowed and remarried while in office. They’re shown with two wives each.

One prez, James Buchanan, was a lifelong bachelor. His niece, Harriet Lane, served as the de facto first lady, socially speaking, so she graces Hutton’s pages just as she graced 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Back to art class. On the day we gather, Hutton is full of fun facts for our students, who are friends and office neighbors of the magazine.

Participants include State Farm Insurance agents Margo and Archie Herring; Susan Sinnott, office manager of Alem Dickey Keel Interior Design; Pam Garner, president of Triad Sales & Recruiting Solutions; Harsha Mirchandani, development director for College Pathways of the Triad; and Moe Miles, who, with his wife Autumn, owns and operates Greenlove Coffee.

As they arrive, everyone wants to make one thing clear: In no way does their drawing ability reflect their professional prowess.

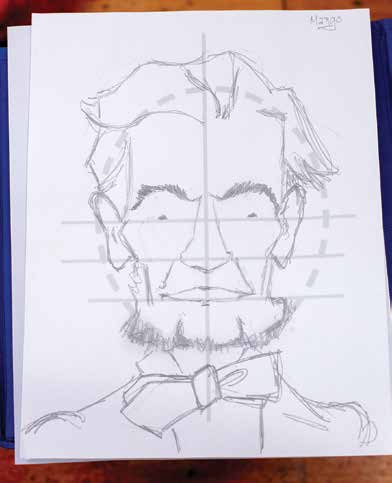

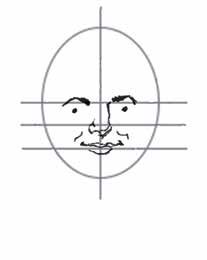

1Notch a “V” just below the second horizontal line on the grid, he tells them. That’s the tip of the nose.

Add flared nostrils and keep your pencils moving upward.

This brings you to the eyes, which land smack dab on the first horizontal line. Start simply: dot, dot. Brows undulate above that.

Now, drop down to the mouth. Abe’s lips fall just above the bottom line.

At this point, the faces on everyone’s papers — as well as the image that Hutton projects on the wall — bear no resemblance to Abe.

The magic happens when Hutton instructs his pupils to add high cheek bones — “question marks,” he calls them — and the sidelines of a lean face.

Suddenly, six Abes emerge.

And so do astonished smiles on the faces of our of budding artists.

They can draw.

The mood loosens as Hutton guides them through Abe’s wrinkles.

Obviously, Abe lived preplastic-surgery era, several people observe. His elevens — worry lines between his eyebrows — also indicate that the late unpleasantness might have been even more unpleasant, cosmetically speaking, owing to the absence of Botox.

A few lines later, Abe’s face is fully fleshed out with his wavy hair, large ears and real-deal bow tie. No clips-ons for No. 16.

He looks fit for a play-money penny in each of the students’ drawings.

“Everybody does it a little bit differently,” says Hutton.

Except for Margo and Archie’s Abes. They’re essentially twins.

What is it they say about married couples? After a while, their drawings of Abe Lincoln start to look alike?

Chitchat flows between our newborn Picassos as Hutton brings up the second subject of the day:

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the wife and later widow of John F. Kennedy. She also founded the White House Historical Association.

There’s another piece of trivia worth preserving.

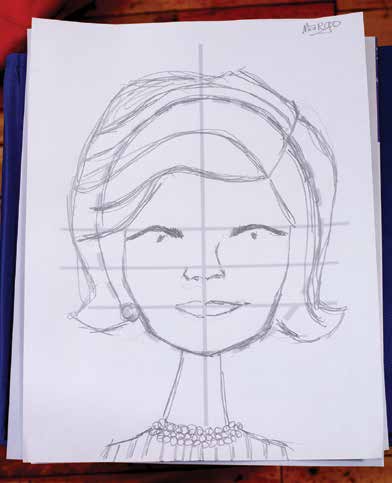

In sharp contrast to Lincoln, Jackie was a style maker, setting fashion standards with her bouffant hairdo, flip curls and pearl chokers.

Hutton flashes his example on the wall and instructs his students to start again with the nose.

“She has a broad nose, but not as broad as Abraham’s,” he says. “Her eyes are going to be well below the eye-line. They’re fairly wide set, much more than ordinary.”

Jackie’s lips, he points out, are rather full, and her mouth turns up slightly at the corners.

“That’s what makes her look friendly,” he says.

By this time, our students are getting friendly with each other.

“Do you need an eraser?” Harsha asks Susan.

“You don’t have any left,” Susan teases back.

They speculate about whether Jackie’s lips were plumped by filler.

When Susan draws one of Jackie’s bob earrings next to her jaw, Harsha joshes that it looks like a cyst: “She’s got to get that thing drained!”

Pam texts her husband to ask what he’s doing at work. She sends him pics of her sketches to flaunt her fun.

Moe is so impressed with his work that he considers adding it to the Greenlove menu.

Next to a decaf Lincoln latte perhaps? A caramel Jack-iat-O.?

These reluctant creatives — who initially wanted to leave their names off their papers for fear of being ridiculed — now want to show off their works.

“I have skills!” marvels Archie, looking at his handiwork.

Margo asks Hutton if he’s ever met an unteachable student.

Every ounce the teacher, Hutton refuses to say yes.

Learning is a process, he says, and the important thing is to stay at the process.

“I try to help them do it better,” he says.

In the end, the class gives Hutton thumbs-up on his teaching ability.

“I think your method is highly effective, the way you break it down,” says Harsha.

Class is dismissed and everyone leaves clutching sketches worthy of the White House — refrigerator.

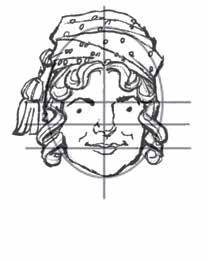

Well, Hello, Dolley!

Try your hand at drawing Greensboro’s

own Dolley Madison

She was the OG of FLs.

Before anyone called the first ladies “first ladies,” Dolley Todd Madison, who spent her babyhood in what’s now Greensboro, shaped what people would later regard as the role of a first lady.

She was married to James Madison, who would become the country’s fourth POTUS, but before that, she handled the White House social life of their friend, Thomas Jefferson, whose wife had died before he assumed office as the third U.S. president.

Dolley, who famously threw small parties called “squeezes” — think what you will — was known as the D.C. hostess with the most-est, which is probably why the Hostess snack cake company once had a line of Dolly (with no “e”) Madison baked goods.

Raise your hand if you remember raspberry Zingers.

Anyhoo, Dolley was on-point, stylistically, and more than a little rebellious for her time.

She made turbans with tassels a thing.

She dipped snuff.

She also turned the White House into a veritable Baskin-Robbins on the Potomac, generously dishing out the frozen confection that Thomas Jefferson, a former ambassador to France, first introduced to the White House as a taste of continental culture.

Let’s face it: if Dolley were around today, the girl probably would be pierced and tatted, though maybe not for her official portrait.

Which brings us to an actual portrait of Ms. Madison. Because no one posted pics — or even took pics — back in Dolley’s day, paintings are the only way we have of knowing what she looked like.

If you want to try John Hutton’s method for yourself, pick up some colored pencils and use the grid we’ve provided to create your own version of DM. Feel free to take some creative liberties and send your best sketch to cassie@ohenrymag.com or drop your work in an in-feed Instagram post and tag us in the image: @o.henrymag.

The winner will receive a copy of John Hutton’s book and a place in a forthcoming issue.

Step 1

Step 2

Step 3

Step 4