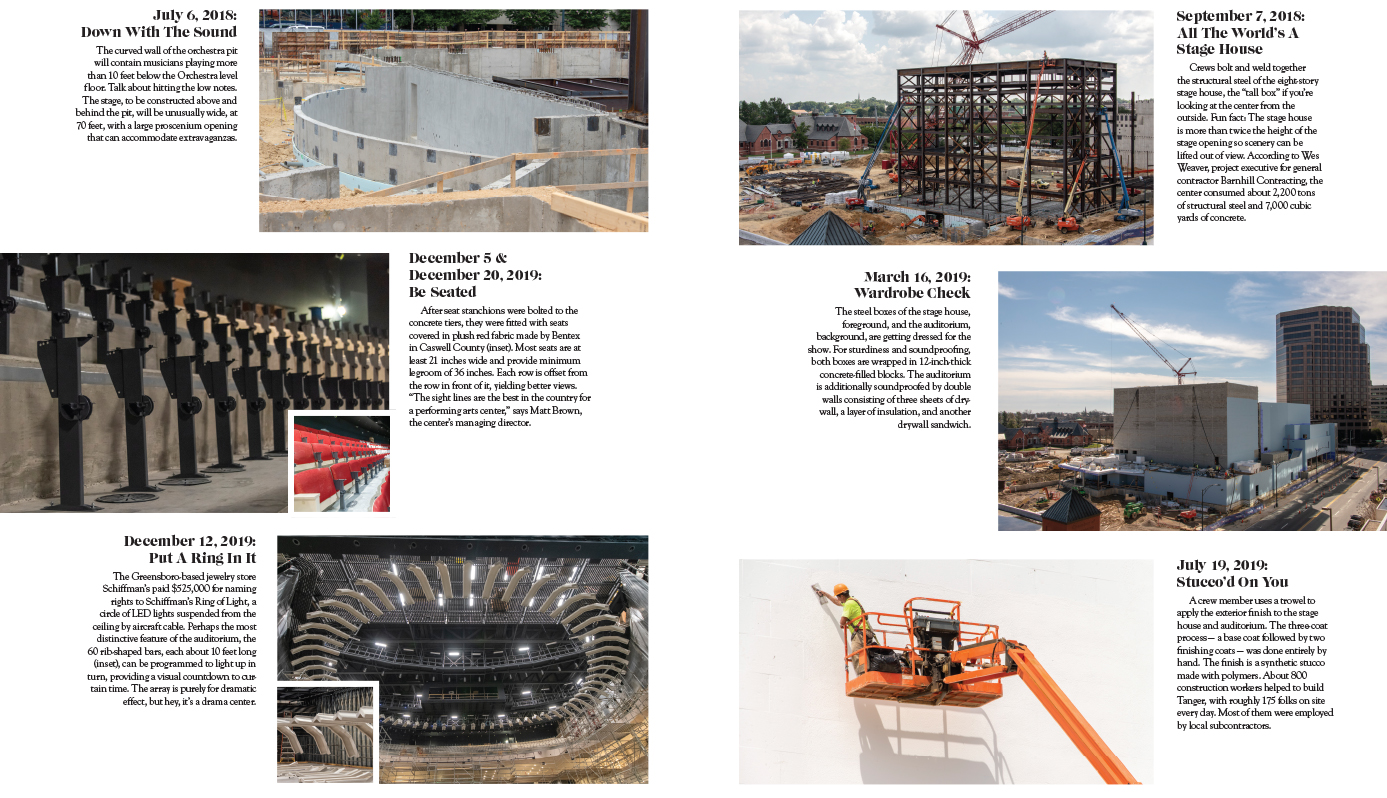

Avid Aggies and organic farmers. Foodies and Philanthropists. High school sweethearts and high-stepping seniors. Meet five couples who share a common passion — and the joy of being together.

True Blue & Gold Aggie Love

Frank & Vicki McCain

By Jim Dodson • Photographs by Mark Wagoner

Frank and Vicki McCain are living proof that timing is everything in the mysterious ways of love.

They met 38 years ago when both were high school students attending a gathering of North Carolina student councils in Raleigh. Frank was president of the statewide organization and president of his senior class in Charlotte. Vicki Hinton was senior class president at Rocky Mount Senior High School Down East.

“He was wearing a Kelly green sports coat and looked so confident and handsome,” she recalls with a laugh.

“Oh, you better believe I noticed her too,” says Frank with a chuckle.

One year later, they were both freshmen at North Carolina A&T State University. Vicki was rooming with a girl from Charlotte, planning to major in accounting. Frank was studying marketing and management.

“One evening there was a knock at our dorm door and there was Frank McCain,” she remembers.

“You’re that girl from Rocky Mount,” Frank said with a smile.

Their love affair began — as many enduring ones do — with a strong friendship, time spent in classes together and conversations around campus.

Two years later, Vicki was attending the Aggies’ away football game against N.C. Central with friends from back home, when Frank happened to be there. He offered to drop off her friends at their campus in Durham after the game and give Vicki a ride back to Greensboro.

Dropping her off at her dorm, he boldly asked to kiss her goodnight.

“Naturally,” she says, “I said no.”

Frank McCain is living proof that faint heart never won a fair maid. He kept asking Vicki out, and she finally consented to a first date to Chi-Chi’s Mexican Restaurant in the spring of 1986.

On the drive back to A&T, Frank calmly spoke from the heart. “I want you to be my wife,” he told Vicki. “And I want you to have my children.”

She was sure her was joking. “I laughed till I cried,” Vicki remembers. “We were just great friends at that point. I couldn’t believe he was serious. But when I looked at him, he wasn’t laughing.”

“We’ll see who gets the laugh,” Frank said with a stoic shrug.

Upon graduation in ’87, she took an accounting position with Cargill Corp. in Memphis, Tennessee. Frank went to work for First Union Bank in Greensboro.

During one of his visits, Vicki informed him that when he left, she was going with him. A more promising job awaited her in Richmond, Virginia. They loaded up her Chevette with her belongings and headed home to Rocky Mount. Vicki soon moved on to Richmond.

From December of 1987 to late summer of ’89, the couple managed to see each other every weekend. During a weekend visit to Georgetown, Frank proposed marriage. Vicki told him she needed to speak with her mother, Lucinda “Miss Tab” Hinton, who affectionately called Frank “Hotdog” because of his name. Vicki also said she needed to pray on the proposal.

They got married August 12, 1989, at Vicki’s childhood church in Rocky Mount. It was really the first time Vicki had a chance to get to know Frank’s extended family.

Something lovely happened before the service. Vicki was all alone in a room, dressed in her wedding gown and watching guests arrive, when there was a knock at the door and Frank’s father, Franklin McCain Sr., stepped in to have a quiet word with the bride.

Franklin McCain was an American icon, one of the four brave A&T State freshman who staged a peaceful sit-in at the Greensboro Woolworth on February 1, 1960 — a moment broadly regarded by historians as a key moment in the birth of the nonviolent American Civil Rights Movement.

“He knew I was nervous and calmly told me ‘You look mighty pretty, Sugar.’” McCain then asked her if she was absolutely sure she wanted to marry his son, she recalls. “He explained that marriage is a serious commitment and that if I had any doubts I was free to change my mind.”

She didn’t. This pleased him. “Big Daddy was such a wise and reassuring man. That meant so much to me. We became such close friends.”

After the couple exchanged vows, the groom couldn’t resist a gentle dig. “I guess I got the last laugh after all,” he told Vicki with a chortle.

Today, Frank McCain carries on the family tradition of public service as vice president of United Way of Greater Greensboro, and Vicki serves as pastor of the Presbyterian Church of the Cross on Phillips Avenue and works as a royalty auditor for Centric Brands. Both are deeply involved in A&T alumni affairs and athletics.

In fact, three generations strong, they may be the poster family for Aggie Blue and Gold.

After graduating from Ragsdale High with high honors (serving as homecoming queen, varsity head cheerleader and student government president as well) daughter Taylor, 25, attended UNC-Chapel Hill and today works as operations manager for a major snack company in Miami.

Son Frank III — whom everyone calls “Mac” — a graduate of Dudley High Academy, is a star footballer whose key interception in the closing moments of the 2017 Celebration Bowl led to MVP honors in a win over rival Grambling State and a perfect 12–0 season for the Aggies. The redshirted McCain picked up two All-America honors and snagged eight interceptions during his first two years, running two of them back for touchdowns, including a 100-yarder against East Carolina for the victory.

Last December, Mac McCain helped guide the Aggies to their third straight HBCU national title with a third consecutive win over Alcorn State at the Celebration Bowl in Atlanta. After battling food allergies and injuries, he is now in graduate school at his alma mater studying agricultural business and preparing for a fourth season in Aggie Blue and Gold.

“We are blessed to have children who are such good people,” says Pastor Vicki. “We’re also proud to be part of the A&T community, which is really our extended family.”

“A&T allowed us all to grow,” agrees Frank. “It’s who we are — and who we will always be. Aggie pride is nationwide!” OH

Providential Pairing

Katie Clark & Branyon Spigner

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

If they get married as planned, Katie Clark and Branyon Spigner won’t have to worry about becoming one of those couples who start to look like each other.

They already do.

With their broad, easy smiles, their clear blue-green eyes and their rosy 19-year-old faces, they could be mistaken for sister and brother.

“I’ve had people say to me, ‘You’re like the same person,’ “ he says.

Their differences stood out the first time they met — or became aware of each other. They were in seventh grade, doing a walkathon on the grounds of Mendenhall Middle School in Greensboro. Katie was strolling with friends behind Branyon, who, having already experienced a growth spurt, was 5-feet-9-inches tall, by far the biggest kid around.

“I was like, ‘Why is there a 16-year-old at our walkathon? And what’s his name again?’ I couldn’t say his name,” Katie recalls.

It’s Branyon, rhymes with canyon.

They had English class together the following year.

“I remember, I heard her talking about a Christian football movie, When the Game Stands Tall. I was like, ‘Hey, I love that movie,’” he says.

They were too shy for conversation in person — she hid behind a locker door to avoid making eye contact with him in the hall — but they struck up a friendship by texting, mostly about their faith in God.

When Katie’s friends threw a surprise party for her December birthday, they invited Branyon.

“Most people gave me gift cards,” Katie remembers. “He gave me a plaque with Proverbs 3:5.”

Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not unto your own understanding.

“I thought that was charming,” she says.

They talked face-to-face. It was a good sign.

“It was like, ‘OK, we can talk without a phone.’” says Branyon.

They held hands at a New Year’s Eve party.

She invited him to a community theater production of Sleeping Beauty, in which she played the lead role.

“It was funny,” Branyon remembers. “The first girl I fall for, I have to watch her kiss a 17-year-old.”

Their own first kiss came a few weeks later, on a snow day when school was canceled. They went sledding then walking in the woods with friends. Suddenly, the friends vanished.

“I think they all planned it,” Katie says of the couple’s instant privacy. “We talked for a while and then he kissed me. It was cute.”

They went to a Christian music festival on Valentine’s Day.

They became each other’s best friends in high school. Their friends called them Mom and Dad. Or KatieBranyon. Neither drank. Both were on student council and participated in the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and in the faith-based organization Young Life.

He joined her youth group at Lawndale Baptist Church.

“It was so natural,” she says. “It felt like we’d always been together.”

He played varsity football for three years at Page High School, and she stayed until the end of every game, partly because she was in charge of the pep club and partly to get post-game pictures of her and Branyon.

“It was nice to have that support,” he says.

They planned to go to different colleges, she to Carolina to study psychology, he to N.C. State to study civil engineering.

She was accepted by both schools, but State offered her a scholarship, and a campus Christian group reached out to her. She changed her mind about going to Chapel Hill.

“It was a God thing,” she says. “It was a bonus that Branyon was at State.”

Now, they live in the same dormitory, in suites one floor apart. When he’s done studying, he’ll text her to see if she has time for a visit. Sometimes, they meet in the dining hall.

Like any couple, Katie and Branyon quarrel at times.

“At first, we didn’t really understand our differences,” he says.

“We tried to look past them,” she says.

“We needed to understand where the other person was coming from,” he says.

“Now it’s more like, “What do you need from me?’” she says.

For a while, they thought they would get married in college, but now they think they’ll get engaged while in college and get married right after graduation in 2023, after he starts a full-time job, possibly with the construction company he will intern with this summer.

Katie has changed her major to communication, with a minor in Spanish, to prepare for a more flexible career should Branyon’s future employer send him to another city.

“All of our ducks are almost in a row,” he says.

They look at each other with the same eyes.

They smile the same smile. OH

Planned Spontaneity

Paul Russ & Lynn Wooten

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by Mark Wagoner

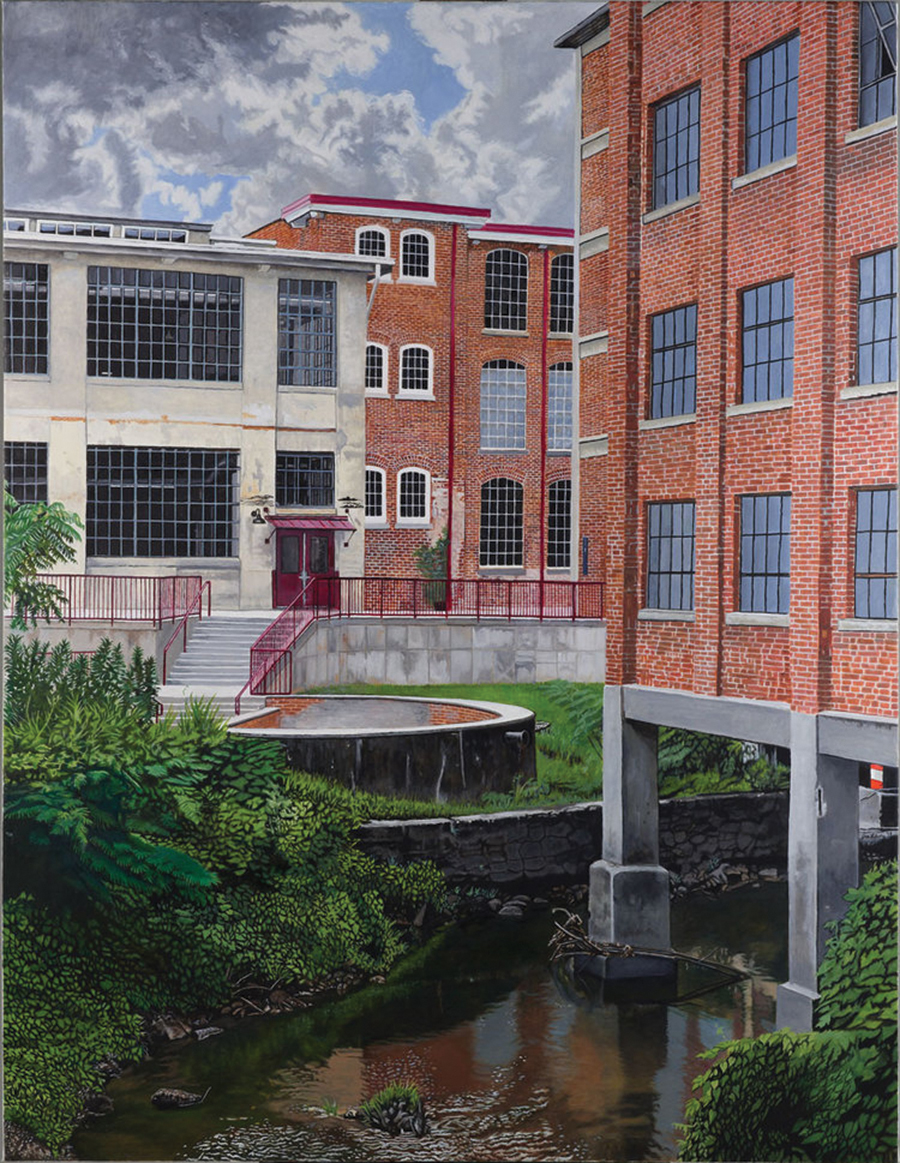

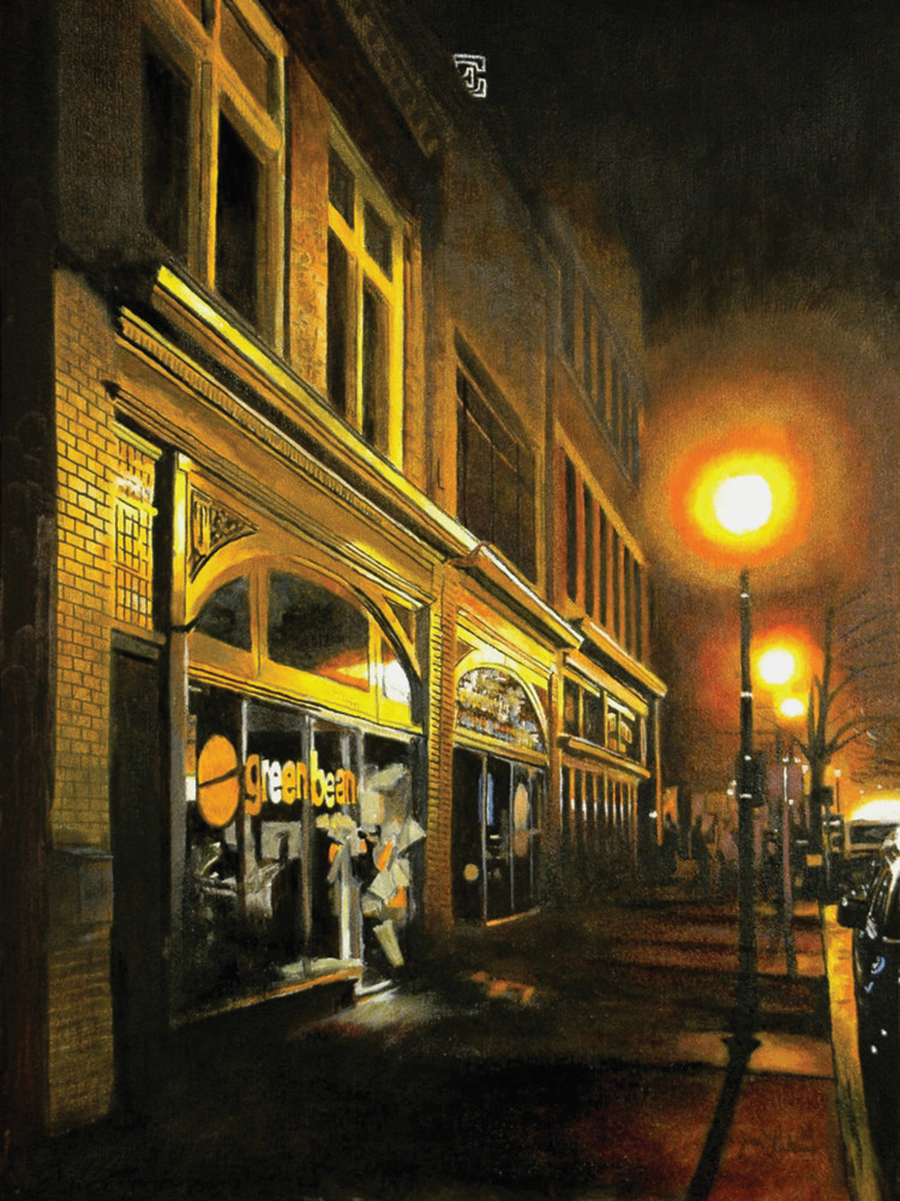

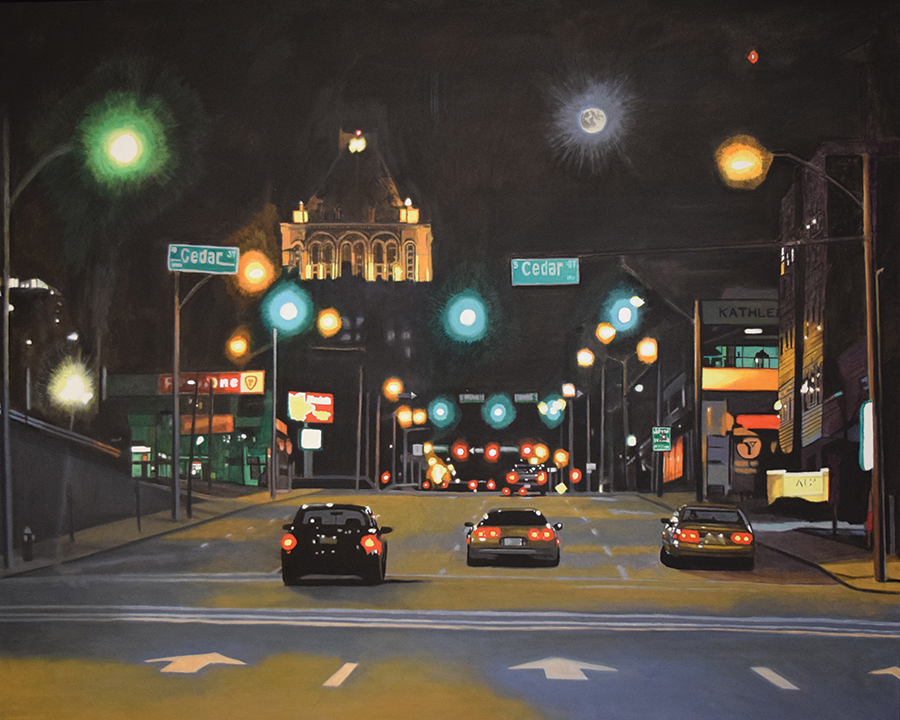

Cooking, art and philanthropy cinch the relationship for high-profile Triad couple Paul Russ and Lynn Wooten.

Food is the extra ingredient: It was in a Triad restaurant that they met and they were married in another, with a celebratory party thrown on a later date at an art gallery.

In 2006, Russ and Wooten had a blind date for brunch at Greensboro’s Green Valley Grill. Then they took the blinders off. “It’s unusual, because less than a month before we had seen each other across a room,” says Wooten, with Russ completing the thought “ . . . at a Durham film festival.”

With a shock of recognition, the pair discovered they lived parallel lives.

They were the same age.

The Russ-Wootens simultaneously attended UNC-Chapel Hill with studies overlapping three out of four years.

They earned the same degree (Journalism).

Russ’ good friend lived next door to Wooten. “And we’d never met!” Wooten exclaims.

“We had to have met, at some frat party, or walking across the quad,” muses Russ.

“Or on an elevator,” offers Wooten.

“Or basketball games at Carmichael,” adds Russ. A bit like the romantic comedy, Sliding Doors, he says.

“We were not meant to meet before we did,” agrees Wooten, who invited Russ to a Durham party. “We were inseparable from then.” Synchronicities abounded.

Each transitioned from journalism to public relations. When they met, Wooten worked at UNC-Hospital; Russ worked at Hospice and Palliative Care of Greater Greensboro.

“We both were involved in nonprofits, volunteering and helping out,” Wooten says. “As corny as it sounds, we both liked giving back,” he adds.

Then there was a shared joy of cooking — and eating well.

“We love food,” he confesses. “There are very few ways we differ. He won’t eat goat cheese and I won’t eat raw tomato,” sighs Wooten.

“I can watch cooking competitions ad nauseum,” confesses Russ.

Both laugh.

The foodies married in 2015 at 1618 West — the restaurant’s first wedding.

For the celebration held at GreenHill, Ibby Wooten supplied a Japanese-made cake topper featuring Lynn snapping a selfie — a signature move. Her brother paused for a selfie during the ceremony. “I did it at the end! I pulled out a selfie stick, popped the camera up, and got the photo with everybody behind us. It turned out great.”

Russ is now vice president of marketing and development for the newly merged AuthoraCare Collective, formerly hospices in Greensboro and Alamance/Caswell. Three years ago, Wooten became vice president of marketing and public relations for the Well-Spring Group.)

In those roles, they meet people who are farther along life’s pathway.

“At Hospice I’ve learned more about living than dying,” says Russ. “We’ve met people with the capacity to do great things.”

Working with seniors and those with fewer days apportioned to them, they also have learned something valuable.

So the couple, who have both done a lot of public service work as volunteers and on various boards — e.g., Triad Stage, Weatherspoon, the Public Art Endowment — discovered the need for “me time.”

“Paul rules the finances,” says Wooten. “I do the calendar.” In which he occasionally writes, “Do Nothing.”

On those special weekends, they may not leave the house, one filled with antiques, books, and an art collection amassed together. Russ is in the kitchen cooking. Wooten reads or naps.

They reserve uncommitted weekends for forays or outings to restaurants they haven’t yet experienced. (A recent such trek was to Acropolis, the downtown Greek restaurant.) “It was great,” enthuses Wooten.

They call this, “planned spontaneity.”

“We love fun, good experiences. It’s a simple life,” says Wooten. OH

Happy Trails

Sue Beck & Bill Haney

By Nancy Oakley • Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

“You really gotta like someone a whole bunch to sleep in a tent and walk every day with a pack on your back,” says Bill Haney with a broad grin. But Haney has done just that for most of the 44 years he’s been married to Sylvia “Sue” Beck.

“I had always wanted to do hiking,” says Sue, now 83, while Bill, whom she affectionately describes as “just a kid,” at 80, “was interested in wherever we both went.”

“Actually, I was interested in her,” he chimes in, his Cheshire Cat grin reappearing.

The two met in the mid-1970s when Sue was completing her master’s in music at UNCG and needing some education courses to fulfill teacher certification requirements. She landed in two of Bill’s classes one summer. An avid athlete, Bill’s interests included cycling and rock climbing, and, as Sue would later discover, swimming and diving. “That’s what really got me interested in him. I saw him diving and wow! He was amazing!” she says with a soft, low chuckle.

They took their courtship slowly, having both been married before, “and not anxious to get into that mess again,” Sue says with her ready laugh. But they tied the knot in 1975, blending families, and working — Sue with the Guilford County Schools, Bill with the Employment Security Commission.

As they approached their late 50s, the couple had heard about classes offered at Guilford College’s Wilderness Center. “Canoeing, backpacking, climbing,” Bill recalls.

“So we took the backpacking thing, and I loved it,” Sue waxes, explaining her deep appreciation of the outdoors and the natural world. “I’m an explorer at heart,” she adds, “but I could never have done it without Bill.”

While she carried “around 35 pounds,” he would shoulder a heavier 45- to 50-pound pack as the two began to hit various hiking trails in the Southeast. “He just sort of put up with it,” Sue laughs.

“There were times when either one of us would have enough for that day and throw a fit,” Bill concedes. Like the time they had run out of food a day before reaching Nantahala Gorge. “I get very grouchy when I’m hungry,” Bill admits. Or the times they’ve been injured, or when their camp stove once blew up. But taking the mishaps — how else? — in stride, Sue remarks, “We’ve had some fascinating experiences and we’ve met some amazing people.” Particularly groups of other hiking enthusiasts they’ve encountered on the Appalachian Trail.

In 1988 the two hiked a southern portion of the famed 2,200 route stretching from Springer Mountain, Georgia to Mt. Katahdin in Maine and would periodically hike various sections of it. “We just jumped around. We’d hike for a weekend. Or maybe during a vacation period for 10 days or something like that,” Sue recalls. “And all of a sudden I said to Bill: ‘You know what? We’ve hiked a lot of this trail, why don’t we just do the whole thing?’”

Under the trail moniker, “NC Pole Cats,” a nod to their use of ski poles for balance and safety well before it became accepted hiking practice, the two completed their goal, encountering a cast of characters along the way: the Four J’s, three guys and their unseen fourth, Jesus; or The Three Little Pigs, three gals who described themselves as “looking like pigs and smelling like pigs,” says Sue. And the ultimate payoff: Mt. Katahdin. “The end of the trail at Katahdin is spectacular,” Sue enthuses. “There’s a beautiful campground at the bottom. Then you have to hike up, up, up.” She recalls going by a beautiful waterfall. And as they got higher and higher, it turned out to be not so much a trail as a jumble of rocks. “Huge rocks. Car-sized rocks” she says. “And they’re all piled up on the top of this mountain. And just before you get to the very end, it becomes a trail again. It’s very challenging.” Here, Bill’s rock climbing expertise was crucial. “I don’t think I could have done it if he hadn’t been there to explain to me where to put my foot next and my arm next,” Sue observes.

By 2001, Bill and Sue earned their AT patches that they proudly wear on the sleeves of their camp shirts, along with their perennially young hearts. They’ve become an example, if not an inspiration to their peers, sharing their experiences with local groups such as the Shepherd’s Center, or Abbotswood, where they live. Its nearby 3-mile loop and regular yoga sessions keep them in shape for excursions to favorite hiking destinations such as Hanging Rock and Grayson Highlands State Park in Virginia, with its “beautiful rock formations and wild ponies,” says Sue. They’ve trekked through Canada, New Zealand and Switzerland, and imparted a love of hiking and the outdoors to their grandkids. And though age has necessitated some modifications — no more 50-pound packs for Bill — the two have “a long life to live,” Sue says, laughing, and as long as they’re able, they’ll continue speaking their love language — step by step. OH

For Love of Family & Good Food

David & Nneka Williams

By Jim Dodson • Photographs by Mark Wagoner

A dozen years ago, David and Nneka Williams made an important decision about their quality of life and young family.

“We decided it was time for a healthy change in the food we ate — realizing that what we were eating was simply not making us healthier,” explains David.

“It was an epiphany for us.”

The roots of this awakening lay in his evolution as a landscaper who, in the early 1990s after graduating from Northwest Guilford High School, started out with New Garden Landscaping & Nursery. Williams eventually opened his own business, having morphed into a specialized personal landscaping designer with a dozen private clients he works with to this day.

Out for an evening in 1998, he happened to bump into pretty Nneka Little — pronounced “Nay-Kay” — a UNCG dance major and ballet dancer who grew up in New York City. David was shy. Nneka wasn’t. They swapped phone numbers but she had to call him first.

Your classic case of country mouse meets city mouse.

“I’m a city girl. If you’ve ever seen the movie Big,” Nneka says with a laugh, “that was supposed to be my life.”

Because David grew up on a family farm in Stokesdale, he had no interest “whatsoever” in returning to the farming life — or so he thought.

Lightning struck fast. The next year the pair were married at a quiet family ceremony in Stokesdale.

When their sons Logan and Gavin were 5 and 3 respectively, it bothered them that both children suffered from allergies and asthma, requiring daily breathing treatments. Nneka also required her own medication for allergies, and everyone in the family was putting on weight.

Fearing years of medical issues, the Williamses boldly switched to a vegan diet and experienced a quick and remarkable turnaround. “Healthy organic food was the answer,” says David. “It healed our bodies and resulted in making all of us dramatically healthier. Within a few years, everyone in the household was off meds and had lost weight.”

Moreover, their shared passion for healthful food led to an exciting new chapter of life. A backyard, raised-bed organic garden fueled their growing knowledge of organic gardening and in 2011 led to visits to a pair of sustainable farms in Saxapahaw.

“That was all I needed to see,” says David, who began meeting with a farm consultant to plan and gather ideas for their future organic farm.

For the next two and a half years the couple searched for the right piece of property, eventually settling on a rolling 13-acre parcel off Church Street extension, in the rural community of Midway, just into Rockingham County.

A week before Christmas in 2015, the Williamses moved into a handsome energy-efficient 3,200-square-foot house they designed and built themselves. Soon thereafter, they completed work on their first high tunnel–heated greenhouse and started building their washing and packing facility, just in time for their first harvest.

Sunset Market Gardens was born.

Today, its fourth year, the farm boasts three state-of-the-art large greenhouses (plus two smaller ones) filled with a bounty of USDA-certified organic produce that looks almost too good to eat — spectacular Asian greens and several varieties of gourmet lettuce, bok choy, baby kale, radishes, beets, carrots, spinach, scallions, plus turnips and collards. Ditto various herbs, ginger and turmeric, and pasture-raised eggs. As February dawns, new potatoes, summer squash, cucumbers and heirloom tomatoes are already planted in immaculate rows, working their way to market. The Williamses even sell organic bread and have an online store. No surprise that their customer base is growing robustly.

The farm’s prime sales venue is the historic Greensboro Farmers Curb Market on Yanceyville Street along with their own ever-expanding farm store, open Wednesday afternoons and Saturday mornings. Sons Logan and Gavin, at 15 and 13 respectively, have grown into impressively polite young men, homeschooled by their mother. They run the farm store and ultraclean packaging operation. Two other mouths to feed and two more pairs of potential helping hands have expanded the Williams family.

“It’s not been a easy life but it’s such a rewarding life,” says Nneka, as she spoon feeds organic veggies to 5-month-old Kieran while keeping an eye on Falynne, age 2, playing in the gated living room. “David is a perfectionist about the farm — his passion — and the boys are learning valuable lessons about work and life and sustainability.

“My mother’s dream was to live in the country and have a farm like this,” she adds with another laugh. “Whenever my parents come to visit, they’re so excited they hardly come in the house because there’s so much to do and see.”

“For us, this is really is a dream come true,” adds David, who continues to beautify the property’s landscape with plans to eventually offer farm suppers and special events on the grounds.

“To think how far we’ve come in such a short period of time makes me humble and very grateful. That’s something we love to share with people who buy our produce and come out to the farm to see how we grow our food — a love of family and good healthy eating.” OH

For more info: Sunset Market Gardens, 346 Woolen Store Road, Reidsville Open: Wednesdays 4 to 6 p.m. and Saturdays, 9 a.m. to 12 p.m.

Phone: (336) 362-1344 | Sunsetmarketgardens.com