The Gentlewoman and Happy Farmer

THE GENTLEWOMAN AND HAPPY FARMER

The Gentlewoman and Happy Farmer

Margie Benbow bought the farm

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by John Gessner

Margie Benbow did not grow up on a farm. But the easygoing former urbanite says, “I wanted to be a ‘country’ Benbow.”

And so she is, living contentedly in a traditional, white clapboard farmhouse nearing a century old. One with generous porches and a wide-open view to acreage planted in fescue and flowers.

Wearing a denim dress with overall straps, Crocs sandals and a red bandana holding back her blond hair, you might guess she has known nothing but life on a Summerfield farm. But you’d be wrong. She is a scientist, lawyer, auctioneer and artist — now farmer — joining the ranks of 24,160 women farmers in North Carolina, where the percentage of women jumped 90% in recent decades.

She’s downright Jeffersonian in her wide-ranging ambitions, not only practicing law while farming, but simultaneously making a serious run at political life last year. No matter that she lost her race for the North Carolina House of Representatives; Benbow maintains a natural sunniness, a goodwill that makes even her losses look like wins.

This is decidedly her super power.

If any of her dreams were easy, she probably wouldn’t even have found them very interesting.

Nine years ago, Benbow said goodbye to the din of traffic and all that comes with it, having lost her physician husband, Dr. Hector Henry, to cancer. Court dockets no longer ruled her calendar — just before the pandemic, she had settled into a rural rhythm largely dictated by Mother Nature.

She acquired not one, but two farms — another is a leafy drive away in the tiny community of Bethany, population 362.

Summerfield, by comparison, is practically a bustling suburb of over 11,000 residents. This, she laughs, is her city residence.

Wandering into the kitchen to prepare a ginger tea, Benbow appraises the space, which is open and oriented to the farmland behind the house. Even inside, she can keep watch on her crops from the dining room table.

She came of age in a pleasant Winston-Salem neighborhood as a “city” Benbow, with three sisters and a brother, relishing visits with the family’s “country” kin. She confides having always envied the life of her counterparts.

She ruminates about the reasons she is smitten with being far from the maddening horde.

“They had a pond. Since I was 4, I’ve wanted this life,” she declares.

Now she, too, has a pond of her own at the Bethany farm near a log cabin where restoration is underway. As further proof of self-reliance, Benbow has tasked herself with learning to make a split-bamboo fly rod — should she ever want to cast off. Online tutorials are daunting. But, then, that probably just whetted her appetite to learn.

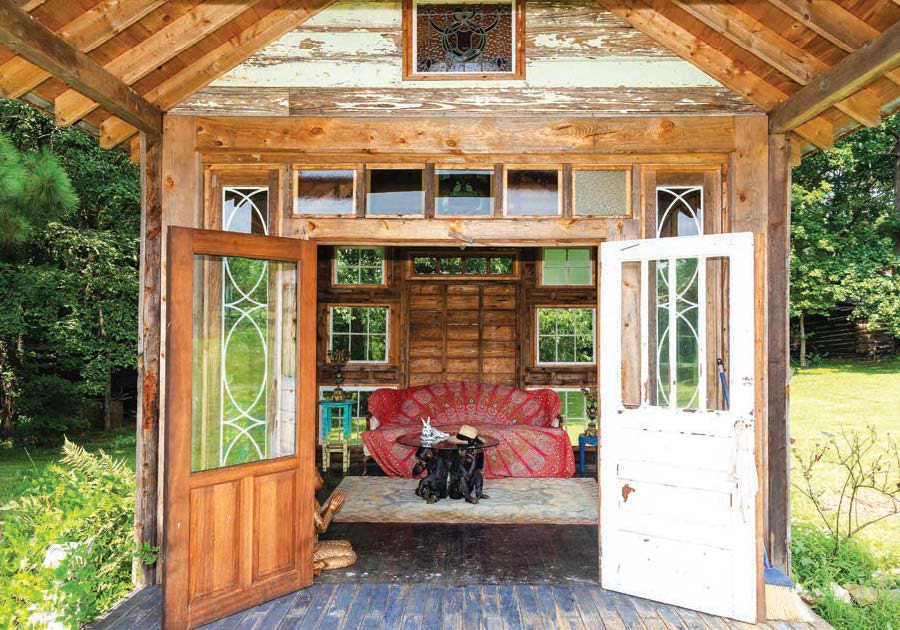

In Summerfield, she has created a sunny, happy haven, the rooms dominated by whimsical, colorful art.

“This is my city house,” she teases, nary a neighboring house in sight. “My country house is 4 miles down the road.” She first bought the Summerfield house and 20-acre farm in 2016. The second farm, bought in 2020, sold at auction. Benbow was the top bidder. Land, she explains, is an addiction.

Then, the pandemic struck and a lockdown ensued. She realized she was going to have more than a small amount of isolation, even in what she calls her “city” house because of its proximity to Summerfield. She admittedly binge-watched Netflix and ate popcorn.

But also, she got busy.

As an avid artist, Benbow weighed the overall aesthetics of the house where she had moved. “It had amazing bones.” The kitchen, centrally located and serviceable, made sense to leave much as she found it, preserving the existing layout. The space includes four sets of doors making it light-struck and airy.

But Benbow explains that the farmhouse was a less daunting project than the restoration of the farmlands whereupon it sits. Much had already been accomplished in the house when she acquired the property, she says. Essentials, like replacing windows. But some things were neglected, like the disintegrating fireplace bricks.

Then she considered ways she could inject her own style. The cosmetics could use some help, she decided. Benbow ripped out the kitchen tile, designing and crafting her own backsplash tile at the Sawtooth Center in Winston-Salem. A hefty butcher’s block, repurposed as an island, required six people to move in as well as joist reinforcement. But once in place, it looked as if had always been there.

The open kitchen, now suitable for a serious cook, features a professional range. But when questioned about cooking, she laughs. “It looks like a cook’s kitchen.”

Cooking? Not her thing.

Benbow points out the most-used “fancy” appliances, giving a throaty laugh: a toaster, a popcorn popper, a Ninja juicer and a coffeemaker.

“That’s about it.” Still, she agrees. The range looks great.

As a rule, where Benbow found original farmhouse details, she kept them. But the ugly and unoriginal popcorn ceiling and cheap light fixtures had to go. Mostly, she “just made it pretty. Calmed it down.”

Since moving here, she has accomplished a lot, steadily ridding the surrounding land of tangled overgrowth. In order to grow flowers (focusing upon pollinators, a passion) she tackled clearing the fields of seven years of tree growth.

Afterward, she used the sawdust from removing all those trees, recognizing it as a compatible medium for planting zinnia. But a storm made short work of her investment in seeds, fertilizer and lime — all laid to waste.

Undaunted, Benbow acquired her second, 50-acre farm using new auctioneering skills from Mendenhall School of Auctioneering. A slew of projects came with the parcel — outbuildings, a log cabin, even a country store. She keeps horses there in a fine new equestrian barn. A mare, she says proudly, recently foaled.

The dream, however, follows a personal tragedy. She and her late husband were birds of a feather. The doctor, medical professor and long-time member of the city council in Concord, was a Colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves Medical Corps. (He made headlines volunteering for multiple Middle East deployments when well past retirement age.)

Benbow reminisces about their meeting at Duke when she was a graduate student working in a lab and he was doing morning rounds as a pediatric urologist. (She nearly went on to medical school.)

Henry had surreptitiously “scoped her out” as she demonstrated to residents how to do cell cultures.

Initially, she was reserved, questioning how he obtained her number when he called her. He thought she might be an ice princess.

Before dating, she grilled Henry.

Had he ever done drugs? Was there another woman that would mind her having dinner with him? And, out of curiosity, what was his age?

“He answered no to the first two.” The age difference didn’t matter.

Three months later, they were engaged, marrying in 1992. She muses about the fact that only one of her four siblings didn’t pair up with a doctor.

Seemingly indefatigable, Henry died on Thanksgiving Day in 2014 at age 75 due to complications from a rare blood cancer. Her smile fades. For seven months following, she describes being “spiritually diminished.”

With Henry’s death, Benbow was forced to begin anew. She literally replanted herself.

Behind her Summerfield farmhouse, a colorful vista unfolds in summer. While she isn’t particularly good with flowers, Benbow shrugs. “I just try.”

Benbow has walked each furrow and hillock.

“Goldfinches, butterflies, all did well,” she muses, pleased that pollinators are appearing — even as she worries about their general decline. She is consumed by the need to support pollinators and began beekeeping, but lost her hives this past winter during severe cold. Still, there are emotional victories. It was a special moment watching deer wading into the sunflowers she had planted.

For someone who was first a scientist, she explains farming, too, is process dependent.

“You have to get into the process, and pray for the outcome. ‘I hope it works,’” she jokes, but is also serious.

Benbow recalls telling Rotarians just how humbling and uncertain it is.

“If you want to find religion, sit on a tractor thinking about those seeds you just spent $4,000 on,” she says, adjusting herself in her chair as if sitting atop a tractor: “You sit on that thing [hoping]. ‘It’s going to work. It’s going to work.’ And pull in all the good vibes of the universe.”

Last year, she lost both sunflowers and corn crops to drought. Losses are a piece of the human condition, as she is acutely aware. As for the romantic culture of growing what you eat and farm-to-table fantasies, she also understands how hard it is. Even basic crops like tomatoes, planted in the same place again and again, lead to soil depletion. Crop rotation is essential. She quickly outgrew the first farm — so acquired another.

With hands thrown up in a gesture of surrender, she laughs about how her best tomatoes are often volunteer plants randomly emerging from the seeds of tossed-out tomatoes. “With no memory of a potential pathogen there,” the science-minded farmer explains. The tenuous balance of earth and farming is a constant seesaw.

If enduring disappointment and difficulty prepare one for the unpredictability of farming, Benbow’s own childhood easily predicted the success of her marriage. Battling adult polio at age 25, her father endured 13 months in an iron lung when his wife was pregnant with their second child. Later, he adapted to walking with leg braces and refused to be a victim. He went on to create the first computing department at R.J. Reynolds.

He was never self-pitying, Benbow recalls.

Her mother, Jane, was a cartoonist in college yet skilled in math. Her father, William, was a poetry-writing engineer. A single thing didn’t define them.

She inherited both left- and right-brain talents from her polymath parents. And — a happy resilience that seems indomitable.

For a time after Henry’s death, Benbow was adrift, listening for an echo that was no longer there. Coping with not being part of a duet is painful.

“Much like in The Magic Flute,” she explains, “when the songs echo.” She confesses to “having leaks” when something triggers tears.

Alpha Awareness Training by Wally Minto led to recovering herself.

“It was basically saying, ‘What did you do as a child, and where was your joy?’ If you get back to the child in your past, you’ll find it.”

In surrendering herself to becoming lost, Benbow reliably found her way back.

Even as she kept her law practice and farmed, she explored further, attending auctioneering school and earning an associate’s degree in visual arts. “I’m a serial learner,” she playfully argues when accused of being a serial degree earner.

She insists she is a happy person, if a struggling farmer — and “even a happy lawyer.” But Benbow questions if Henry could have thrived here.

The problem was, Henry was a “bug magnet,” she jokes. Sensitive to mosquito bites, he was therefore never as keen on the country life. Plus, she would never have asked him to give up his multidimensional life.

A pensive Benbow looks outside towards the recently planted fields where flowers grew last year. Her mother often quoted a line attributed to Emerson. “The Earth laughs in flowers.”

“We had laughter in the house,” she adds wistfully.

“If you went into Mom’s house, it had a lot of energy,” she says. “Every surface was decorated with something she had made.” Each room of the farmhouse contains some of Benbow’s artwork. Her art is charged with color; exuberant, zestful.

Suddenly sheepish, she looks around her home, and adds, “This is turning into that!” After a beat, Benbow yelps.

“I’m turning into my mother!”

Behind her, the cloud cover breaks. Suddenly, sunlight drenches the fields, which seems to undulate, newly golden, where seedlings have barely emerged.

Benbow swivels, orienting her perspective to better see. Tender beginnings, which, if luck holds, will bring vigor, growth and maturity. If temperatures don’t swing madly, if there is rain and not drought, if pestilence stays at bay, there will be harvest and not heartbreak.

“Flowers are more beautiful,” she murmurs in a low register, her whole face softening into a hopeful smile.

Of course. She already sees the flowers.