Growing Season

GROWING SEASON

Growing Season

Under the Bertrand family, a 42-year-old flower farm continues to flourish

By Dawn DeCwikiel Kane

Photographs by Becky VanderVeen

The Bertrands’ home can be busy, and sometimes a bit cramped and messy, much like that of any other young family.

“This is our life currently,” Carrie Bertrand says, as she walks through the living space she shares with husband Patrick and their children Ayla, 12; Silas, 10, and Ellie, 6.

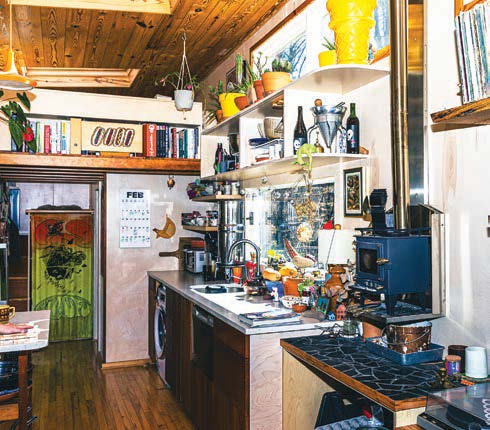

The family of five, plus three cats and a dog, live in a camper on Maple Grove Flower Farm, which they own and operate. (And let’s not forget the family’s pet frog, who doesn’t enter the camper, but resides in a terrarium in a building next door.)

For now, home is a 2008, 38-foot Cedar Creek Silverback, a heated and cooled fifth-wheel camper. It’s large enough for Ayla and Silas to have separate, small bedrooms, while Ellie’s bed is in another area of the camper. There’s also a primary bedroom.

They hope to soon replace it with a newer, larger living space. But for now, their camper has become not only a home, but a homeschool and home base for their flower farm on Wild Turkey Road in rural Whitsett, 15 minutes east of downtown Greensboro.

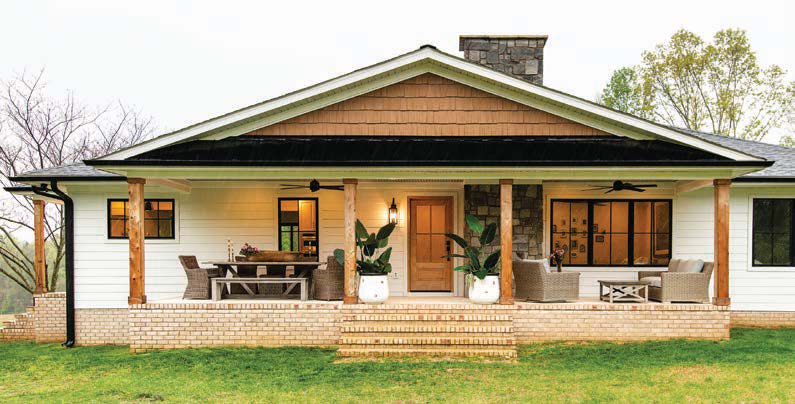

Their flowers bloom in 13 commercial-scale greenhouses covering 32,000 square feet of indoor, irrigated growing space. Nearby, on their 7.5 acres of land is a 2,500-square-foot barn built in 1913.

The Bertrands grow ornamental plants in pots, flats and hanging baskets that they sell primarily to garden centers. They grow only chrysanthemums outdoors.

They don’t sell cut flowers, or plants for eating.

No sign announces the spot just yet.

By mid-morning on this March day, Patrick and Carrie have already been out on the farm for a few hours.

“So many people have no idea about this side of agriculture,” Patrick says from a building adjacent to the camper, wiping the sweat from his face while Carrie eats a yogurt-and-granola snack and the kids build a fort.

Patrick, now 47, grew up in Greensboro, the youngest of two sons of radiologist Margaret L. Bertrand and anesthesiologist Scott A. Bertrand. He graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder with a B.A. in economics. Carrie, 42, grew up in a small town outside Columbus, Ohio. She studied elementary education at Wheeling Jesuit University in West Virginia.

The couple met at the Church on 68 and married there more than 13 years ago.

Carrie taught school. They owned a landscaping business. But Patrick gradually realized that the work would grow increasingly strenuous.

The couple looked for something that would involve the whole family.

“Patrick was gone from sun-up to sundown most days, and we wanted a change from that routine,” Carrie recalls.

That routine indeed has changed. The family lives together — and works together.

The children help. Ayla maintains plants with three high school girls who work part-time. Silas enjoys fixing small machinery with his dad. Ellie is in the kindergarten-grade level and “excited about it all,” her mother says.

After dinner, the Bertrands enjoy typical family fun. Patrick might take Ellie to dance class; twice a week, Carrie drives them to American Ninja Warriors in Thomasville to prepare for competitions or takes Ayla to rock-climbing. Wednesday nights are for church. Tuesday nights are typically free, so they might cuddle in the camper to watch a movie.

Life on Maple Grove Flower Farm begins at 5:30 a.m. Carrie makes breakfast in the camper and teaches their children for three hours or more. She also manages the farm with Patrick, doing greenhouse work and accounting.

Although the camper has a bathroom, the family primarily uses one of two bathrooms in the adjacent building that they call the “head house.” The head house doubles as a family kitchen and a break room for the small staff. And of course, it’s home to the family frog.

In a separate section of the head house, they stage carts of plants that will go into pots.

The flower farm has two growing seasons.

The Bertrands and a handful of employees plant 40-plus varieties of tiny begonias, geraniums, zinnias, salvia, sedum, and other annuals and perennials, and grow them for six to eight weeks. All in all, they plant about 200,000 plugs — tiny plants — for spring sale, Carrie says.

For fall, they plant about 25 varieties of pansies, chrysanthemums, violas, snapdragons and dianthuses — plus poinsettias for the holiday season.

They sell the plants wholesale, primarily to garden centers in the Triad and beyond, from Winston-Salem to Raleigh and into southern Virginia — much like original business owner and grower Greg Welker did before them.

Among their customers are Guilford Garden Center in Greensboro, Saviero’s Tri-County Garden Center in High Point, Southern States in Chapel Hill and Asheboro, A.B. Seed at the Piedmont Triad Farmers Market in Colfax, and Logan’s Garden Shop in Raleigh.

“We would love to also be selling directly to some of the landscapers,” Carrie says.

“But we felt there was so much to learn just on what he [Welker] had built already,” she adds. “He had a very successful business and had amazing relationships with the garden centers in the area. We certainly want to do what he has been doing with excellence before trying to add a bunch of new stuff.”

By one recent survey for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, North Carolina ranks 10th among the 50 states in floriculture, both in terms of dollar sales and number of operations.

Their floriculture business has nearly tripled in volume from the landscape business they had previously owned for almost 18 years. “Triple sales, probably triple expenses,” Patrick says.

They feared they would lose a significant customer when New Garden Landscaping & Nursery closed its retail side in December after more than 50 years and focused on its commercial and residential landscaping. But in March, Guilford Garden Center put down roots in a second location, the Lawndale Drive shop where New Garden’s retail and garden center space had once thrived.

Stephanie Jones, who owns Guilford Garden Center with her husband, Elliott, understands what it means to run a small family business. “We have to look after each other,” she says.

Maple Grove Flower Farms’ humble beginnings took root with Greg Welker.

A native of Washington state, Welker started the flower farm in 1983, when he had finished a year-long horticulture program at a botanical garden on Kauai in Hawaii, followed by a year-long program at Ball Seed in Chicago.

His grandfather, Dan Welker, had purchased the land in 1956 and eventually passed it on to Welker’s father, Raymond Welker. Welker used that land to grow the flower farm, naming it for maple trees that stand across the road.

“It was hard work,” Welker says. “But at the end of the day, I got to walk to the greenhouses and see all the beautiful flowers, and I knew that everything I sent was going to make people smile.”

A chance encounter with Patrick blossomed into a sale.

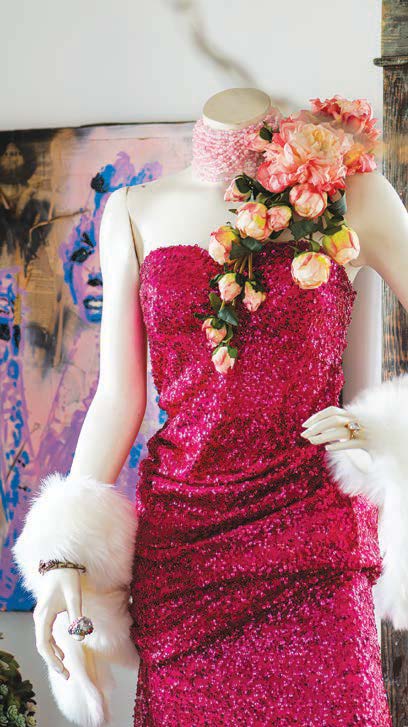

When Welker opened the back of his 26-foot enclosed box truck one fateful day in fall 2022, Patrick’s eyes widened at the sight of vibrantly colorful ornamental flowers in trays of pots on shelved carts.

Patrick admired row after row of planted fall flowers — giant pansies in purples, yellows, whites and burgundy, cabbage and kale in hues of green, white, purple and pink.

“He seemed to have a library of plant material in the back of his truck, beyond what was dropped at our stop,” recalls Patrick, who had closed his landscaping business and was working for another.

After that tailgate meeting, the entire Bertrand family visited Maple Grove Flower Farm.

Patrick and Carrie remember Ayla, from a young age, picking early blooms from azalea bushes at their former home to make floating bouquets or other artwork.

“We didn’t need to sell her on the idea of moving to a flower farm,” Patrick says.

Believing that they would buy the farm, he went to work for Welker in January 2023 as an apprentice.

In May 2023, they sold their cul-de-sac home on Oak Hollow Lake in High Point.

“We would love to say that it was smooth sailing, getting from one place to another,” Carrie says. “But it was a process that tested our patience and our faith.”

They finally got a loan from the Small Business Administration to buy the flower farm, sealing the deal in July 2023.

Welker still worked there two days a week that first fall “to get us into the groove,” Carrie recalls.

He is now 63, retired and living in Chapel Hill.

“He built everything on this property from the ground up, so he knows how to fix everything,” she says. “And Patrick has had to learn, because you can’t call somebody every time you need something fixed when you have an operation like this going on.”

At first, Carrie knew few of the flowers’ names. She could identify a petunia, but didn’t know a pansy from a viola, especially with the variety of flowers that they planted and sold for spring.

She learned fast.

For four to six weeks in the winter cold and the summer heat, they get breaks from farm work, but order plugs for the following season through Ball Seed, from farms in West Virginia, Illinois and New Jersey. Winter brings maintenance work.

That gives them time for family trips.

Cold affects the wallet when propane field heaters need to run.

This past winter, several irrigation lines burst in empty, unheated greenhouses and had to be repaired.

In late January, they began planting for their second spring season.

Within a few days, they filled 6,100 pots with potting soil to have ready for the first shipment of plugs that arrived the following week.

They want flowers to look picture perfect when they sell. They ensure that they are tagged with plant names, and are clean and free of pests. They pinch off each head so that they become fuller — just as customers prepare to buy them.

Mid-March brought the first sales of their second spring season. Patrick delivered flowers in a truck four to five days each week.

Patrick and Carrie talk of the future.

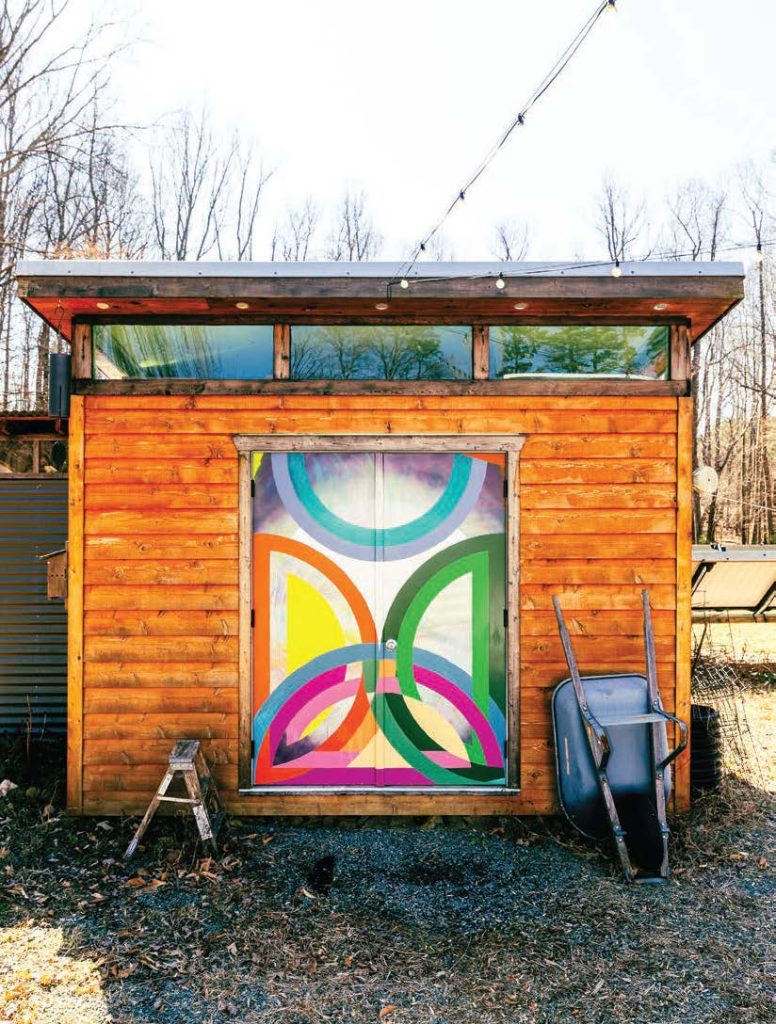

Last December, they converted one of the greenhouses into a winter wonderland.

They hosted events there that featured Santa and Mrs. Claus, a life-size Candyland game, cookie decorating, and hot cocoa.

Carrie hopes to eventually plant sections of flowers where parents can bring their children and both groups can learn.

They envision welcoming school groups for field trips.

They would like to open a small market on the land where they sell leftover items they grow, plus goods and produce from local artisans.

“We want to add some community involvement,” Patrick says.

They hope that at least one of their children someday will run Maple Grove Flower Farm. “Either our daughters or son will have the opportunity if they would like,” Patrick says. “I have a feeling at least one of them will want to continue building the farm, from the flowers to the community outreach.”

Want to schedule a visit to Maple Grove Flower Farm? Email maplegroveflowers@gmail.com, or call or text 336-209-3607.

To learn more, go online to maplegroveflowerfarm.com or to the Facebook page for Maple Grove Flower Farm.