The Wright Stuff

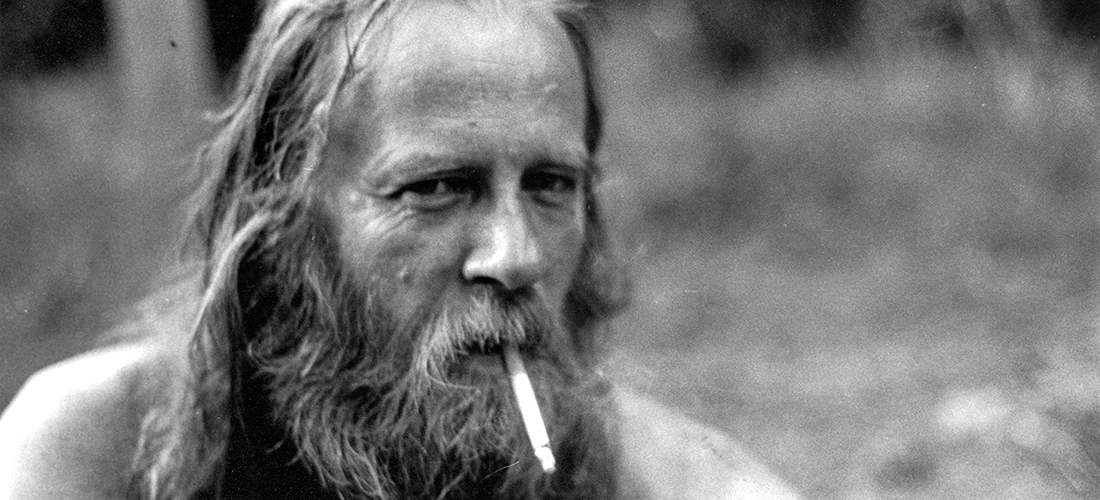

Clinton E. Gravely’s odyssey in Modern architecture

By Ross Howell Jr. • Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

Architect Clinton E. Gravely is a lithe, erect man — even taller in the cowboy boots he’s wearing. He’s standing with his wife Etta, waiting to greet me at the entrance to their home.

Parked at the rear of the house is a tan Corvette. I walk along a curving stone pathway. The house before me is low-slung, built of stone and wood and glass. At the entry is a fountain, its feature an abstract metal sculpture of a horse. The water sparkles in the sunlight, and the sound is calming.

“Did you notice the chain downspouts?” Gravely asks. “The Japanese use them.” I’d missed that detail, but notice it now.

The Gravelys’ 7,000-square-foot house is situated well back from the road, near the center of an 11-acre parcel of land. Just beyond the house I see stables.

“Oh, I’ve been around horses ever since I was a kid,” Gravely says. “We don’t keep them anymore. But they used to have free range of the place. Except I told my three girls they couldn’t ride them up on the patios. Of course the girls are grown and on their own. We use the stables for picnics or family gatherings now.”

We shake hands and Gravely opens one of two massive oak doors, the prominent feature of the entrance. The doors are made of varying shades of wood, cut and carved in geometric shapes.

“Made by hand,” Gravely says, closing the door behind us. Inside the house the textures are stone and wood — cedar, pine, and redwood. Natural light floods the foyer.

“I’ll leave you two to talk,” Etta says. She makes her way down the hallway.

There are potted plants beside the door. Before us is a glass-walled atrium and beyond, a living area and dining area.

I comment on the chandelier in the foyer.

“Yes, that’s my design,” Gravely says. “I drew up that fixture and the ones in the living and dining areas.”

Gravely tells me he worked with his associates for a year to complete the drawings for the house. Construction began in 1974 and wasn’t completed until 1977. He coordinated the work of subcontractors and did much of the work himself.

“I grew up in the construction business,” Gravely says. “My father, William Jr., and my grandfather, William Sr., were contractors in Reidsville. They built modest family homes, gas stations. When I was in fifth grade, my father would drive me out to their job sites after school, and I’d help with clean-up or odd jobs.

“Sometimes customers would ask Dad for house designs,” he continues, “so when I was in high school, I’d do simple drawings for him to present. Then one summer he put me in charge of a building crew. These were guys I’d grown up with. We had to keep everything on schedule, get a structure framed up and roughed in, stay ahead of the subcontractors, who came in to do the finish work.”

Gravely and his crew roughed in seven houses that summer, an accomplishment that still fills him with pride. “When I graduated high school in 1955, I decided to go to Howard University to study architecture,” Gravely says. “I was just going to stay a year or two, learn a few things, so I could help my father with his business. But one day when I was back home, I saw my high school principal, and he said I ought to go ahead and get a degree.”

It was then that the budding architect realized one of the benefits of studying at Howard. “They had working architects come in and review students’ work, so it wasn’t just professors looking at what you’d done — I noticed that these architects who came, they were driving fancy sports cars, and they dressed sharp, and I thought this architect thing could be pretty interesting,” Gravely remembers.

“I saw the Corvette outside,” I say.

“Yes, they tease me over at North Carolina A&T. Sometimes I’ll sit in on a class, review student work, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s Gravely. He’s the one who always shows up driving the Corvette and wearing cowboy boots.’”

He shakes his head.

“Anyway, one of those visiting architects at Howard reviewed a project of mine and said he thought I had a future in the business. So I got more serious about my studies.

“Of course, I’d never seen any Modern design — what we called ‘contemporary design’ back then — working with my father and grandfather in Reidsville,” Gravely says, smiling to himself. “Then I took a class that included the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. His use of stone, wood, and glass to let the outside inside. His use of water. I don’t know — it just spoke to me. I thought, that is the way people should live. I knew then I wanted to do Modern design.”

When he graduated from Howard in 1959, Gravely, because he’d been in ROTC, was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, with the Army Corps of Engineers. “My job was to coordinate small construction jobs on the post. There were about thirty people on staff, some of them surveyors, some of them trained architects. It was good experience,” he says.

“But I wanted to come back to North Carolina. I got job offers in D.C., but none here, where I’d be able to work some with my Dad. I’d answer an ad in the paper, get invited in for an interview, and then there would be a problem. I remember one place in particular.”

Gravely pauses and picks up the thread.

“I showed up for my interview, and the secretary looked surprised when she saw I’m African American. She kept me waiting for hours. Then she went back to somebody’s office and came out and said the owner’s nephew had decided to take the job.”

I gaze out one of the big windows on the back of the house. It overlooks an expansive stone patio with another fountain — this one featuring a dancer sculpted in metal. Beyond are grass and trees, the canopy dappling the light on the stone.

“Then I talked to Ed Loewenstein,” Gravely says. A native of Chicago and graduate of MIT, Loewenstein moved to Greensboro in 1946. His wife’s stepfather, Julius Cone, provided business and personal contacts to assist Loewenstein in building his architectural firm, Loewenstein-Atkinson. He was the first white architect in North Carolina to employ black architects.

“Ed and I really hit it off because he was a big admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, too. And he was open to recruiting minorities to his firm. He had two black architects working with him then, and he told me one of them, William Gupple, had agreed to take a position with a firm in New York. So Ed said to come back in three months.

Returning to Greensboro in 1961, Gravely joined Lowenstein’s firm as “an ‘architect in training,’” he recalls. “I still had to pass the boards in order to be licensed. I worked with a black guy named Edward Jenkins. Ed and I worked in an office away from the other people, and we had a separate restroom. You know, restaurants, hotels . . . everything was segregated back then. Usually things went fairly well. Sometimes a contractor would object if he saw it was Ed or me making an inspection. But Ed Loewenstein would always back us up.

“The American Institute of Architects (AIA) was supportive of African Americans, but there was a white group called Greensboro Registered Architects and they did not want black members,” Gravely says. “Eventually they admitted me, but a few years later, the group disbanded.”

He passed his license exam and went to an AIA meeting in Wilmington to be inducted — the only minority to do so at the time. “No one came up to talk to me, except for one man. He asked me, ‘Why do you want to be an architect? Only black people will be your clients, and they don’t have any money.’ It’s funny, we talked and talked that night, and he and I became friends. As it turned out, we both moved here to Greensboro to practice. We’ve been friends a long time.”

Gravely and I walk into the dining room. There’s a magnificent table he tells me is fashioned from African wood, and around it, eight chairs that any collector of Modern design would covet. Like the others, the room is full of light.

“When I started working for Ed Loewenstein, I figured I better come up with some kind of specialty that would help me bring in business for the firm,” Gravely says. “So I signed up for a course at A&T about designing and building fallout shelters. As it turned out, the guy teaching the course was working on a book, and Ed gave me a 6-month leave of absence to help him finish writing it. So afterwards, if we had a shopping center project, Ed would say, ‘Well, Gravely here knows how to build a fallout shelter for your center.’

“Then one day I was working with a client on a shelter, and the client says, ‘Why don’t you just help me with the shopping center, too?’ And I explained I was under contract with Ed; I couldn’t do something like that. But Ed said to go on and help him. I’d talked with him about launching out on my own someday, and Ed was all right with that. Here, let’s go in the living room.”

We walk from the dining room to a room with a massive stone fireplace reaching to the ceiling. There’s a large, semi-circular sofa that mimics the curve of the fountain outside.

“Have a seat,” Gravely says. As I sit, I kid him about the vintage television console in front of us.

“Doesn’t even work anymore,” he says. “We just haven’t hauled it off.”

“You should keep it,” I say. “A period piece.” He grins.

“When I set out on my own, I had some key people who signed on to join me,” Gravely says. “But it didn’t take long for me to realize there wouldn’t be enough work in Greensboro to support the business.” So on weekends, I’d drive over to Durham, or Raleigh or Charlotte, and look around the right neighborhoods. If I saw a sign where people were going to put up a church, or some other building, I’d write down the information and phone them the next week.”

He started getting callbacks and in time, Clinton E. Gravely and Associates grew to twenty-six people. “We were registered to do business in eight states and the District of Columbia. Now my partners and I aren’t so young, you know, so we’re down to nine people. We just take the jobs we really want,” Gravely says.

“But since we opened the doors for business in 1967,” he notes, “We’ve completed close to 900 projects. That includes a hundred churches, several multifamily housing units, some child care facilities, and the university library at A&T. That’s a pretty good run.”

Given circumstances, what could anyone do but agree with him? And admire. OH

Ross Howell Jr.’s novel Forsaken, published in February by NewSouth Books, was recently nominated for the Sir Walter Raleigh Award for fiction.