Footsteps of the Fathers

FOOTSTEPS OF THE FATHERS

Descendants of the Greensboro Four support a legacy — and each other

By Ross Howell Jr.

This month, our Greensboro community observes the 65th anniversary of the 1960 February 1 sit-in at the downtown F. W. Woolworth’s “whites only” lunch counter.

There’s a parade in front of the old five-and-dime, now the International Civil Rights Center & Museum on Elm Street, dedicated on a bitterly cold morning in February 2010.

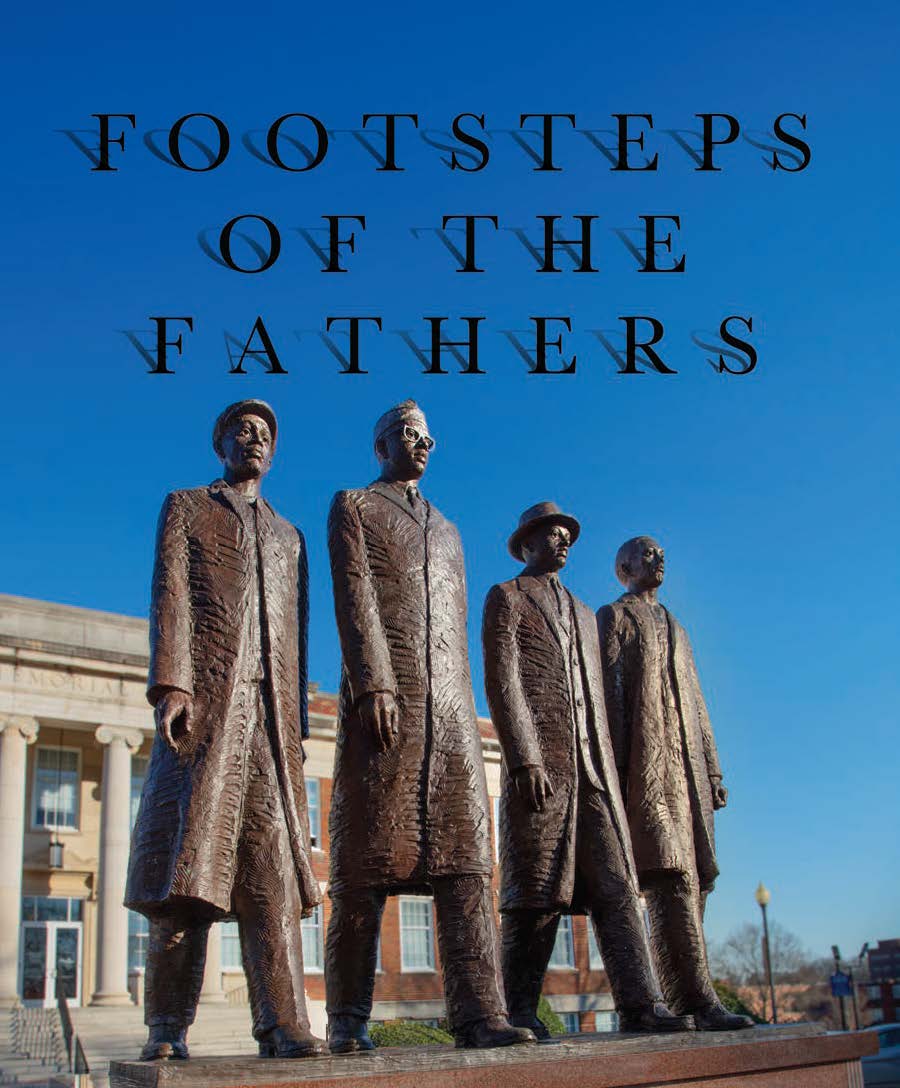

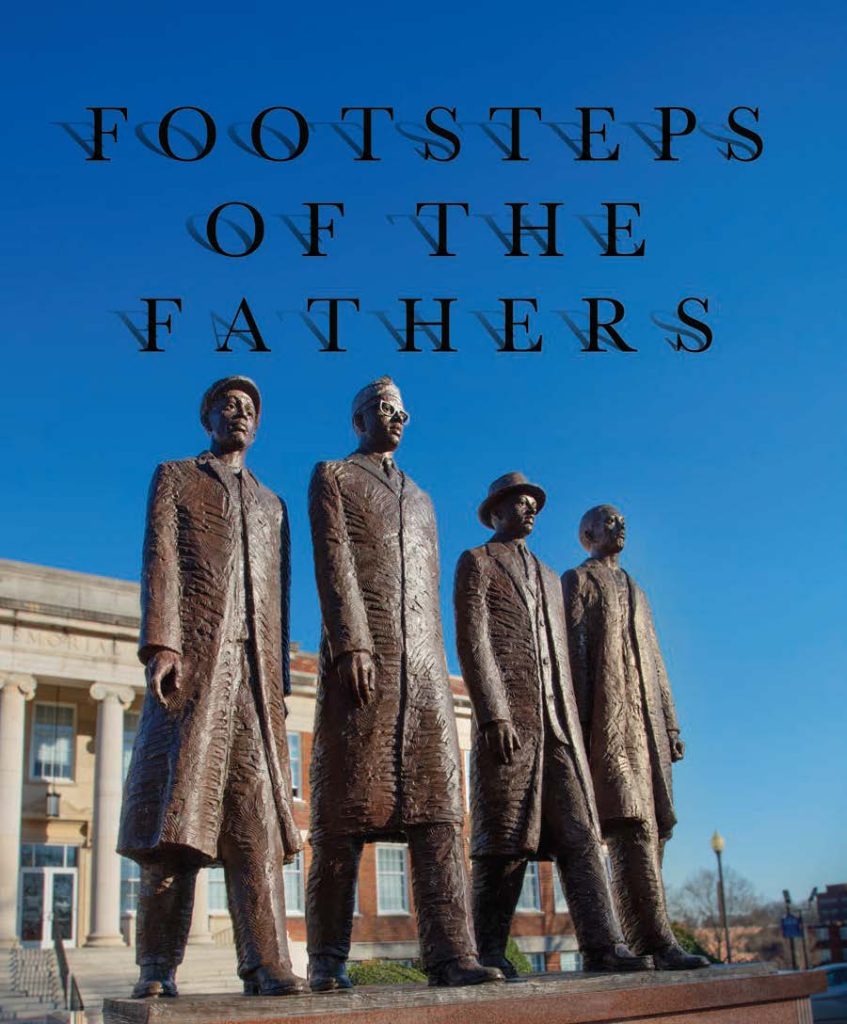

As is customary, a wreath is placed on the February One statue, also known as the A&T Four Monument, on the N.C. A&T campus. It memorializes in bronze the four freshman students — David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan) and Joseph McNeil — who, in 1960, walked from the A&T campus to downtown Greensboro and straight into Civil Rights history.

Sometime during the observance, members of the Richmond, McCain, Khazan and McNeil families will gather for a meal and conversation, just as they have for years, thanks to the generosity of Dennis and Nancy Quaintance of Quaintance-Weaver Restaurants and Hotels.

“I’m so grateful,” says Frank McCain Jr., president and CEO of the United Way of Greater Greensboro. “Every year, Dennis and Nancy join us in a private dining room at their restaurant.”

“It’s a time for us to have fellowship together,” McCain Jr. adds. “It’s a wonderful thing. There are no newspaper photographers around, no television cameras — we can have real, family conversations.”

McCain Jr. stresses how closely the Richmond, McCain, Khazan and McNeil families are knit. “We’re like blood relatives,” he says. “Remember, our fathers were extremely close. They were best friends — all brilliant minds, strategic thinkers, passionate in their beliefs.”

“And they made sure that their children got to know each other well,” McCain Jr. adds. “The Greensboro Four’s children are connected, their grandchildren are connected, and it will always be that way,” he says.

McCain Jr. believes that the four A&T students understood early on that what they were about to do would not only become a proud legacy but also a burden of responsibility that would be challenging to bear.

Think of the four young men in the iconic photograph or the bronze statue.

On the left is David Richmond. He was the first to pass away — in 1990 at the age of 49. It was on his shoulders that celebrity seemed to rest most heavily.

Born and raised in Greensboro, a popular student-athlete at Dudley High School, Richmond entered A&T with a sense of purpose. But after the sit-in, he grew uncomfortable in the limelight. His studies suffered.

Because of his activism, many locals labeled him as a “troublemaker.”

Richmond left A&T and found work. But after repeated death threats, he moved away to a community in the North Carolina mountains. Later, he made the decision to return — Greensboro was home.

Wrestling with depression and alcohol, Richmond struggled to find a job.

“He had been blackballed,” McCain Jr. explains.

Despite the turmoil in his father’s life, David Richmond Jr. remembers him fondly.

“We would always get together with the families in February,” he says. “I remember Dad driving us to those events when I was little.”

Richmond Jr. attended Wake Forest University on a football scholarship — making ACC Player of the Week his freshman year and playing in the Tangerine Bowl.

He remembers classmates asking him if his father had something to do with the sit-ins in Greensboro.

“I told them yes,” Richmond Jr. says. “I was proud of what my dad had done.”

When a football teammate asked him to talk about his father in front of a class, he hesitated. He didn’t think he could do his father’s story justice.

“So I thought, why not get it straight from the horse’s mouth?” Richmond Jr. says.

He invited his father to speak and sat in the back of the classroom, listening along with everyone else.

“I learned so many things I’d never heard,” Richmond Jr. says.

He recalls thinking at the time, “Here I am, the same age my father was when he walked into Woolworth, and all I’m thinking about is when’s the next campus party.”

When his father died, Richmond Jr. felt lost.

“I wanted to represent him, but I’m not comfortable in front of crowds,” he says.

A big help to him was the tall figure next to his father in the historical photo and statue.

“Franklin McCain was my godfather,” Richmond Jr. continues. “We were always tight. I remember visiting him in Charlotte — we could sit down and talk about anything,” he adds.

With McCain’s encouragement, Richmond Jr. went on to represent his father at the dedication of the February One statue on the A&T campus, the official opening of the International Civil Rights Center & Museum and the recognition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“I remember telling Frank Jr., someday he would have to step into his father’s place,” Richmond Jr. says.

He was right. Richmond’s godfather, Franklin McCain, passed away in 2014 at the age of 73.

McCain Jr. struggled with his father’s death, which, like Richmond’s, seemed to have come too early.

“When my father died, I could not have handled it as well as I did without the other families,” McCain Jr. says.

“They all came to town immediately, and I didn’t have to tell them what I needed them to do for me and my brothers,” he continues. “They knew what they needed to do.”

McCain and Richmond had been roommates their freshman year at A&T, and Khazan and McNeil lived in the same dormitory. When they discussed their frustrations and fears, they also talked about how to support each other.

When McCain Jr.’s father graduated from A&T and left Greensboro for Charlotte, his wife, a Bennett College alumna, had already found work in the city’s school system. But McCain couldn’t find a professional position at all.

“My father had moved away from Greensboro,” McCain Jr. says. “But he hadn’t moved far enough.”

Like his former roommate, Richmond, he’d been blackballed.

McCain took the only job he could — as a custodian with a chemical company in Charlotte.

“But as fate — or Divine Providence — would have it, he became the custodian in the C-suite, where all the senior executives, including the president, had offices,” McCain Jr. says. And from time to time, the president and the custodian would chat.

One day, the executive asked his father, “Franklin, have you ever thought about going to college? You’re very articulate, you’re a sharp guy.”

And his father replied, “Well, actually, I went to college. I have two degrees — in chemistry and biology.”

“Then why in the hell are you cleaning up the bathrooms?” the president asked.

“Because this is the only job I could get,” his father answered. “I tried to get a lab job here and they told me there weren’t any.”

McCain Jr. chuckles.

“Less than 10 days later, my father had a job in the lab,” he says.

“He worked for that company for 35 years,” McCain Jr. continues. “And when he retired, it was from his office in the C-suite.”

After his retirement, McCain often spoke at Charlotte high schools, encouraging teenagers to finish their academic work.

“My father lived long enough to meet all his grandchildren,” McCain Jr. says, “But he didn’t really get to see the fruits of his labor. We’ve been able to live the dream that he envisioned.”

McCain Jr. tells me his brother, Wendell, attended UNC as a Morehead Scholar and went on to become a Wall Street banker and venture capitalist. Wendell has a son who is a senior at Stanford and a younger son who’s attending Carolina — also as a Morehead Scholar.

“And my youngest brother has a child who is a senior at High Point University,” he says, “and his other child is a sixth grader.”

McCain Jr. goes on to say that his oldest daughter graduated from UNC and is the chief operating officer of a large snack food company in Miami, Florida. His son, Franklin III, is his grandfather’s namesake. Nicknamed “Mac,” he enjoyed a very successful collegiate football career at A&T and now plays in the NFL.

“I think that if my father were alive,” McCain Jr. says, “He would feel like — you know what? If he and those other three had not done what they did, maybe none of us would’ve had these opportunities.”

Next to the tallest figure in the February One monument — McCain stood 6-feet-2-inches and weighed more than 200 pounds — walks the smallest, Jibreel Khazan — who was said to weigh 130 pounds, soaking wet. But whatever Khazan lacked in size, he more than made up in eloquence and charisma.

Born Ezell Blair Jr. in Greensboro, where his father taught at Dudley High School and was active in the NAACP, Khazan graduated from A&T in 1965. Labeled a troublemaker like the others, he moved to New Bedford, Mass., joined the New England Islamic Center and changed his name.

Recently, a New Bedford public park was named for Khazan, honoring his years of dynamic community and youth group leadership.

Khazan, now 83, will be joining the family gathering this month in Greensboro.

Khazan’s son, Hozannah, lives in Atlanta, Ga., where he is a self-employed business telecom consultant. He tells me that he is regularly in touch with New Bedford family and friends.

Not long ago, he was on the phone with a buddy.

“Hey, I saw your dad out walking the other night,” his friend said. “It was 11 o’clock at night and it was snowing. I pulled over and offered him a ride, but he just kept going!”

“That’s him,” Hozannah laughs. “He’s still full of energy!”

Interested in computers since he was a teenager, Hozannah enrolled at A&T in 1989 and majored in industrial technology, a five-year program.

“I tell people I was born in Massachusetts, but North Carolina made me a man,” Hozannah says. “A&T was a real turning point for me.”

He tells me that, at times, his legacy felt overwhelming. But being able to talk with McCain Jr. was a big help.

“I made sure to be available to spend time with Hozannah because I had already lived what he was about to go through,” McCain Jr. says.

He told Hozannah not to make his college years stressful by trying to live up to people’s expectations. His father lived inside him and there was no changing that, McCain Jr. advised Hozannah, but he would have to find himself, find his own pathway in life.

“Because I was young, I was resentful,” Hozannah says. “But we’re like brothers. We don’t always agree, but we aren’t afraid to voice our opinions.”

Hozannah says that when he reached his 30s, he was better able to embrace his father’s legacy.

“I realized that I was representing a greater community,” he continues. “It’s a lot of responsibility, but I wouldn’t change it for the world.”

The figure striding next to Khazan is Joseph McNeil, who was born in Wilmington. Right after he graduated from a segregated high school, he moved with his family to New York City.

The next fall, he returned to North Carolina to enroll at A&T, where he joined ROTC. It was on his bus trip returning to campus from Christmas break — wearing his uniform — that he was refused service at a Greensboro hot dog stand.

For McNeil it was the final outrage. His fury was the call to action for his friends on February 1.

He would go on to graduate from A&T in 1963 with a degree in engineering physics and was commissioned as a second lieutenant is the U.S. Air Force. After service in Vietnam, he retired from active duty but continued in reserve service.

McNeil retired from the U.S. Air Force Reserve as a major general with numerous decorations. While a reservist, he also pursued a career in finance.

McNeil met his wife when he was stationed in South Dakota. She is Lakota — a direct descendant of chief Sitting Bull.

McNeil is 82 years old and is not expected to attend the family gathering this month. But his son will be there.

Joseph McNeil Jr. attended Sitting Bull College and lives with his family on the Standing Rock Reservation, Fort Yates, N.D. He is CEO of the area’s sustainable energy and community development organization.

A year ago this month, the North Dakota Monitor reported that the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe was celebrating a multimillion-dollar electric vehicle charging network project in Fort Yates —administered by McNeil Jr.’s organization.

McNeil Jr. told the newspaper he was overjoyed to see a group of local middle school students attend the event because the new EV infrastructure represents a much larger generational transition to clean energy. In the article, he said, “I was able to relate to them how our culture is involved in renewable energy as we talk about our relationship to the Earth. That was really important.”

The legacy of the Greensboro Four is complex, and the walk four young men took on a cold February day has led their descendants down diverse paths.

When the International Civil Rights Center & Museum was dedicated, Joseph McNeil sat down for an interview.

“We were very ordinary people,” he said, “with very ordinary lives to live.”

But what is an ordinary life? What were the four A&T freshmen seeking?

“There are certain things that everybody wants,” Frank McCain Jr. says. “You want to be able to live a decent life. You want to have food for your family. You want to live in a place that’s peaceful and safe. You want your children to grow up and be whatever they want to be in life.”

Four young A&T men were determined to show themselves and their families the way. And what a journey it’s been. OH

For more information, visit the International Civil Rights Center & Museum website, sitinmovement.org. The center and museum, the restored site of the 1960 F. W. Woolworth Company sit-in, recently was named a National Historic Landmark, the highest recognition awarded by the National Park Service.