Seasons Greetings

SEASONS GREETINGS

Since the 1800s, America has been sending the very best

By Cynthia Adams

Dale Kearns, a Greensboro postal carrier, is accustomed to the crushing volume of holiday cards mailed out each and every year by well-wishing Americans — the annual estimate exceeds 1.3 billion.

“One customer on my route sent over 100 Christmas cards last year,” says Kearns, with a business-as-usual shrug.

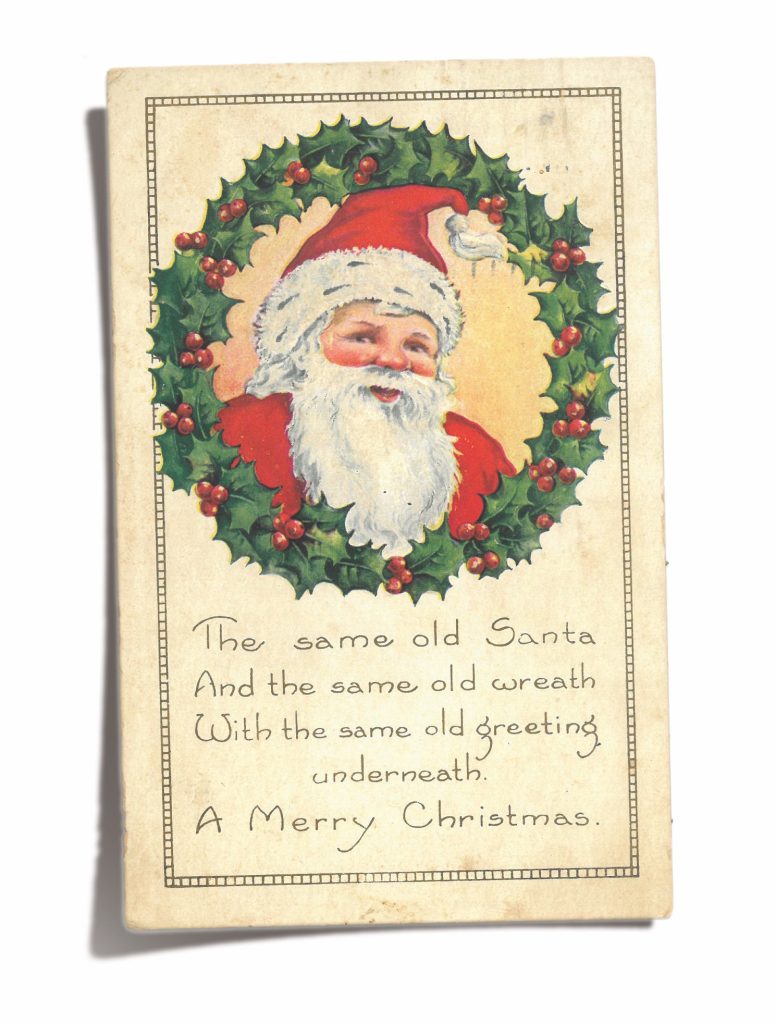

New Year greetings — which are hardly a new concept, by the way — escalate that figure higher. In local designer Todd Nabor’s private collection of vintage cards, shown here, there are as many New Year greetings as Christmas ones, dating from the late 19th to the early 20th century in age.

Long before the advent of folded cards tucked inside an envelope, a postcard — cheaper and vastly easier to send than a personal letter — changed the game in the late 1800s.

But don’t think that postcard messages were necessarily short. A 1918 postcard to Mrs. Adeline Shoppell in Greencastle, Ind. wished “Many Happy Days in your New Year,” with the sender squeezing a long message into the cramped space on the reverse side that promised a letter soon.

In 1924, Larisse Justice mailed a poinsettia-embellished postcard to Miss Hazel Hill in Greensboro. “Flowers will early fade away/But my wishes will last for many a day.”

And what a bargain! Holiday postcards cost only a penny to mail in early-20th-century America, equivalent today to about $.18.

Seems the whole notion of personal greetings even predates the Egyptians and Romans, who dispatched letters (especially on birthdays) written on papyrus and scrolls via fleet-footed couriers.

The sending of New Year’s greetings is attributed to China’s Emperor Taizon, who inscribed messages on gold leaves to his ministers during the Tang dynasty. The idea caught on with the general population, who wrote messages on rice paper. The practice of holiday messaging slowly crossed cultures and continents.

While the Romans may have left Britannia, the custom of letter writing remained. Over the centuries, rice paper, papyrus and scrolls gave way to stationery and envelopes.

By the Victorian era, posting personal greetings was what well-mannered folk did come the holidays. But Henry Cole, the busy founder of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, faced a dilemma. Having neither time nor personal couriers to deploy a holiday scroll to his hundreds of admiring friends, he innovated.

Wishing to avoid a social faux pax — failing to send a cheery gift or letter in reply was bad form — Cole, in 1843, conceived of a standardized postcard greeting. As the British “penny post” made holiday communiques cheap and more popular than ever, he had a Christmas greeting postcard designed and printed for his own use, hoping to keep himself in good social standing.

In time, Brits took to the idea, which further spread throughout Europe. Eventually, German immigrant Louis Prang migrated to America, bringing the concept with him.

In 1875, Prang printed a simple postcard featuring roses and “Merry Christmas.” Americans embraced the concept with gusto. By the early-20th century, postcards were a craze.

The Hall Brothers postcard presses began rolling in 1910. By the 1920s, folded Christmas cards in envelopes had grown in popularity. In 1928, the brothers embossed the “Hallmark” brand on the envelope flap — an idea borrowed from minting gold.

“When you care enough to send the very best,” the slogan we’ve all come to know, debuted in 1944. In the same timeframe, Hanukah cards emerged as options expanded. Slowly, too, Americans began sending personalized cards featuring family photos or supporting a favorite charity — a concept that quickly crossed the pond back to the U.K.

Today, Hallmark alone offers more than 2,000 designs and hundreds of boxed sets. At least 2,500 other American businesses compete for their market share of the greeting card business.

Yet there were greenbacks still left on the holiday table. What said you cared even more than the Hallmark logo?

A holiday-themed stamp.

By 1962, the United States Postal Service debuted holiday stamps — lagging far behind in recognizing another way to commodify the holidays. Seems Austria lapped us by 25 years, debuting holiday stamps in 1937.

Canada introduced holiday stamps in 1939 and Cuba in 1951.

Today, stamps commemorating Diwali, Hanukah and Kwanza reflect a diverse range of holiday traditions.

Hewing to tradition, this year’s “Holiday Cheer” stamps feature a Whitman’s chocolates style assortment of all-inclusive images: amaryllis, cardinals, fruit on a branch and a wreath.

This year, too, philatelists can scoop up re-released favorites “Holiday Elves” and “Winter Whimsy” — miniature pieces of artwork to adorn each and every letter.

But in an era of hastily composed texts and digital greetings, do recipients still care about receiving old-school, holiday snail mail?

Overwhelmingly, yes. Online surveys strongly indicate the majority still prefer receiving a paper greeting card, including the younger demographics — who understand digital fatigue as well as anyone.

Bad news, perhaps, for USPS’s hard-working Dale Kearns.

But good tidings for those who trouble themselves to find, write, address, stamp and post those millions and millions of cards he and his colleagues deliver to each and every door across the land.

Seems the very act of putting pen to paper, extending good wishes to one and all, is an act of engagement — of personal connection. For the faithful senders of greetings and recipients alike, a gift.