Who the Folk

12 DAYS OF CHRISTMAS

Who the Folk?

The N.C. Folk Fest celebrates a decade with a worldly line-up

By Billy Ingram

“It’s our 10th anniversary and we’re coming home,” North Carolina Folk Festival Chief of Staff Savannah Thorne says, confiding that this year’s downtown musical gathering will strike a slightly different chord. From September 6–8, under new Executive Director Jodee Ruppel, some familiar headliners you’ve come to expect will take the stage, but, Thorne concedes, “we’re also packing the weekend full of musicians specifically from North Carolina. We really want to show off the best of our state.”

I suspect the term “Folk Music” has calcified in American minds — buffoonish imagery depicting raggedy-looking banjo plunkers, jug huffers, spoon clappers, corncob smokin’ hillbillies or perhaps six-string-strumming hippies packed into VW vans goin’ to San Fransisco with flowers in their hair.

I asked Savannah Thorne, who holds a degree in ethnomusicology from UNCG, about the protoplasmic catalysts in our region responsible for the earliest percolations of this widely misunderstood genre. “Folk music in North Carolina goes all the way back to the early times,” she tells me. “From the 1700s to the 1800s, you have Irish and Scottish immigrants settling in Appalachia, often indentured servants who managed to gain some wealth and acquire a piece of land.”

That cultural absorption bumped up against indigenous tribes forced into higher elevations after white settlers appropriated ancestral lands. “Then you have enslaved people who are also up there trying to make a living,” Thorne adds. “And all four of these cultures start to weave together folk music.”

Societal injustices from that period meant that rhythmical utterances were often the only legit methods of expression allowed to the powerless. Out of that desire to communicate, came the banjo and guitar from West Africa, rich singing traditions radiating outward from indigenous cultures, Irish and Scottish heritage gifting us with the fiddle. All of these melodious manifestations slowly unified into what we refer to as “old time,” the wellspring of folk music. After cotton mills lured workers from these emerging cultures down from the hills, harmonically aligning with Gullah immigrating from the coast, the Piedmont sound was born. Just one of a kaleidoscopic array of regional folk iterations.

Think of folk as an all-encompassing but never-to-be-finished tapestry, resplendent in hues of blues, jazz, hip-hop, rap, country, Tejano — whatever form the music takes, the underlying thread is authenticity rooted in cultural identity.

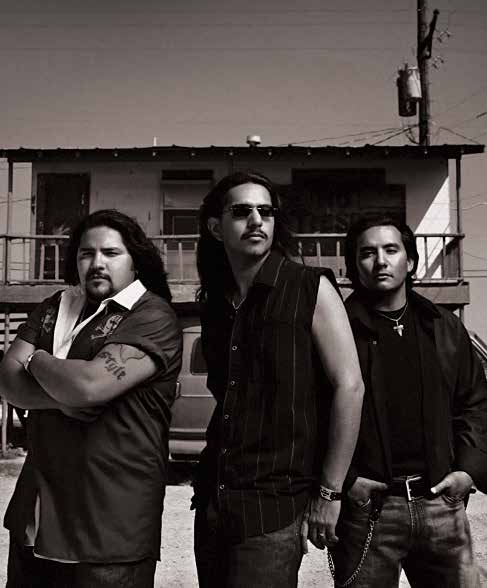

“Ethno USA is a partnership program that we have through the festival,” Thorne says about an underpinning of the Folk Fest we don’t see. “They’re a really fantastic example of international music sharing.” The Ethno program is a two- to three-week conference held in various cities around the globe, where musicians are flown in from all over the world to collaborate, fine-tune their skills, and expand each other’s musical horizons. “Then they play their music at the North Carolina Folk Festival. So you could hear anything from songs being shared from local indigenous communities to music from Chile, from Argentina, from Russia, incorporating all of these different languages.” There is a shift in booking the festival this season. Instead of mass attractions such as Grandmaster Flash or George Clinton, who have both performed in past years, there’s a rock-steady beat of high-calibre entertainment across myriad musical fields. Look for Lumbee Indian- and Oglala Lakota-rooted guitarist and songwriter Lakota John; Grammy- and Country Music Association-nominated husband and-wife duo The War and Treaty, who scored the hit single “Hey Driver” with Zach Bryan, leading to them opening for the Rolling Stones in July; Texican rockers Los Lonely Boys, whose infectious 2004 Grammy-winning No. 1 hit “Heaven” has never stopped lighting up jukeboxes. Then, closing out the festivities in a mellow tone will be Chapel Hill string band balladeers Mipso, who’ll bring down-home to downtown. Musicians in town from around the Tar Heel State embody that spirit of stylistic assimilation: traditional Appalachian steeped crooners Holler Choir out of Asheville; Pentecostal gospel-inspired Dashawn Hickman Presents Sacred Steel featuring Wendy Hickman; the electric R&B sounds of Charlotte’s Emanuel Wynter; then there’s ice cold country-time refreshment from this year’s barnstorming semi-finalist on The Voice, Tae Lewis.

This year’s festival will go a long way to rectify a fatal flaw I’ve complained about for, well, a decade — that there wasn’t enough emphasis on local musicians. “I feel like in a lot of ways Greensboro has been overlooked when it comes to the North Carolina music scene,” Savannah Thorne observes. “This is a rebrand for the festival. We really want to focus on making Greensboro the musical hub of the East Coast that we all know it is.”

I wonder at times if this city suffers from a municipal form of imposter syndrome, a subconscious belief that artists remaining in Greensboro must somehow be inferior to those that fled for more lucrative locales. The way music distribution is set up today, location is irrelevant. In the past, one needed to relocate to New York, L.A. or some other show-business hub to be in the game. That’s no longer true; artists are free to stay, and many are choosing to do so.

This year’s local lineup should forever dispel any possible imposter syndrome dysphoria. In addition to the Sam Fribush Organ Trio (see this month’s “Wandering Billy,” page 45), Colin Cutler and Hot Pepper Jam’s juke joint jive will have audiences bouncing like rod puppets. Many band members of Unheard are graduates from UNCG’s esteemed Miles Davis Jazz Studies Program, a defining undercurrent in their seemingly unstructured yet somehow traditional sounding jam sessions. Grinding out unbridled, guitar-driven Southern grit is Old Heavy Hands, firing up a live set embrued with anthemic energy.

As for Savannah Thorne — she’s dreaming big. “My goal for the Folk Festival is to be the largest free festival on the East Coast in the next two years.” That would entail attracting over 200,000 enthusiasts to downtown Greensboro. “Already the festival has a $20 million impact on Greensboro as a result of the jobs created and all the musicians that end up getting paid.” By focusing on North Carolina musicians this year, she adds, “We have a really fantastic return on investment in that way, and we’re putting our money back into Greensboro.” With a singing style rightfully described by Blues Blast Magazine as having “an uplifting, otherworldly quality,” North Carolina based composer-performer Rissi Palmer apparently has a protean refusal to drop that proverbial needle before letting it sail into a single groove, even when it proves to be highly successful. This Grammy-nominated artist released her latest recording just last summer, an inspirational three-song EP entitled “Still Here”, demonstrating that, not only is she indeed persistently present, but, armed with vocals as perfect as pearls, she’s a righteous songwriter with plenty to say. Tuned-in people are listening . . . Residing in Durham, Rissi Palmer has been allowing that inner songbird to soar since her childhood; “I actually have a picture of me at age four, standing on a milk crate to reach the microphones.” At 19, she was offered a record deal from Terry Lewis and Jimmy Jam but, “I ended up turning it down and didn’t get another deal until I was 26.” That signing resulted in her 2007 freshman album, Rissi Palmer, from which the single “Country Girl” catapulted this uncaged canary to the attention of the public, becoming the first Black woman in two decades to hit the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart. That same year, she debuted at the Grand Ole Opry, subsequently appearing at the White House and Lincoln Center. Coincidentally, this all took place just as Taylor Swift’s first chart-topper, “Tim McGraw,” was kicking up country dust alongside her. I had to ask. “This was at the beginning of both of our careers,” Palmer recalls with a chuckle. “We played quite a few new artist rounds together for radio stations. I was her opener for a music festival in Wisconsin — she was a baby at the time. I think she was 15.”

While Rissi Palmer’s first album was unabashedly country it’s safe to say, over the course of six ensuing recordings, assorted singles and videos, and after thousands of miles circling the globe, her direction and perspective are ever-evolving, “As I’ve gotten older — thanks to being an independent artist — I’ve had an opportunity to explore different sides of my influences. So I don’t know that it’s particularly fair to people who are traditional country artists to call what I do country.” She began calling her style “Southern Soul,” a boldly-blended Chex Mix of country, R&B, gospel, pop, “and all those things that I listened to and loved as a child.”

Written in 2014, initially recorded in 2018, Palmer’s stark protestation “Seeds” gets a galvanic redux on “Still Here”. It’s an uncomfortable yet ultimately uplifting ballad that reverberates as profoundly as “A Change is Gonna Come,” Sam Cooke’s puissant,

cri de coeur of the early-’60s. “I wrote “Seeds” with Deanna Walker and Rick Baresford,” Palmer explains. Baresford has written #1 country hits for icons like George Jones while Walker is a prolific tunesmith teaching songwriting at Vanderbilt University. “We’ve been writing songs together for years.” Having grown up in St. Louis, Missouri, with close friends in the nearby Ferguson community, Palmer confesses the idea grew from a sense of powerlessness surrounding the 2014 murder of 18-year-old Michael Brown. “I wanted to say something, but, to be perfectly frank with you, I couldn’t think of anything positive to say — and I tend to be a pretty positive person. I understood why people were angry, why they were hurt.” When running across a quote from Greek poet Dinos Christianopoulos — They tried to bury us, they didn’t know we were seeds — inspiration hit. “I was like, that’s the way to look at this.”

Palmer had the misfortune of releasing an album in October 2019, subsequently booking all of 2020 to promote it. But, like everyone else, she ended up at home, “with my kids, teaching questionable math and making bread.”

That’s when the idea of her “Color Me Country” radio program came about. “One of my best friends was teasing me,” she says. “She was like, ‘Girl, you need to put all this information that you have about country music and do something with this and not just talk to me on the phone about it.’” In 2020, Linda Martell’s “Color Me Country” album, which the show is named after, celebrated its 50th anniversary. Palmer began by dialing up other country artists she was acquainted with. “I wasn’t exactly sure what this was going to be, but I wanted it to be conversations — not interviews. That’s why I started with people that I knew. We’re now in our fourth season and it has blossomed into exactly what I wanted it to be.”

Demeanor tornados his self-reflexive pop smoke, charged with je-ne-sais-quoi energy, into the atmosphere, a major highlight of the weekend. Born and raised in the Gate City, “I come from a very musical family,” Demeanor mentions casually. To say the least. He began playing banjo and bones around the age of 12, partially inspired by his aunt, Greensboro’s own Rhiannon Giddens. “She started the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Sankofa Strings when I was just learning what a banjo was. I grew up traveling around with her, listening to the music. It was just something so different than what I was listening to.” This young man mostly had New Edition, Bobby Brown, and hip hop CDs spinning at home but, “I’d go out with [Giddens] to these old-time festivals, bluegrass festivals, and I was like, whoa, this is very vibrant.” Keep in mind, this was before his aunt’s astonishing rise to fame, before landing her MacArthur Genius Grant, winning two Grammys and a Pulitzer, and NPR proclaiming her one of the “25 Most Influential Women Musicians of the 21st Century.”

Rhiannon Giddens. “She started the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Sankofa Strings when I was just learning what a banjo was. I grew up traveling around with her, listening to the music. It was just something so different than what I was listening to.” This young man mostly had New Edition, Bobby Brown, and hip hop CDs spinning at home but, “I’d go out with [Giddens] to these oldtime festivals, bluegrass festivals, and I was like, whoa, this is very vibrant.” Keep in mind, this was before his aunt’s astonishing rise to fame, before landing her MacArthur Genius Grant, winning two Grammys and a Pulitzer, and NPR proclaiming her one of the “25 Most Influential Women Musicians of the 21st Century.”

As a teenager whose mother was Giddens’ tour manager, Demeanor (he was Justin Harrington then) accompanied his family on the road during summer breaks from school. “We’re packed into a 10-seater van, just hoofing it in Missouri and the Methodically, Demeanor built a reputation as an independent artist the old-fashioned way. “There weren’t that many venues, so I was playing house shows. It was like bootcamp.”

In 2019, he participated in One Beat, a fellowship where musicians from some 20 countries come together to write and perform new music. Two years later, he became the first rapper to perform a full set at the Newport Folk Festival. “They were kind of first looking at me as — a rapper who plays the banjo? Like, is this a gimmick? Or what is this?”

But, as Demeanor is quick to affirm, rap music is folk music. “I don’t separate the root from the branch,” he explains. “I think that when it comes to music, we separate roots as its own thing. Whereas I’m kind of looking at it as, hey, even our roots have roots, and then those roots have roots.”

Immersed in a purposeful state of unwavering reinvention, transcending generational euphemisms, Demeanor attacks his original compositions with an unmistakable fearlessness, an almost undetectable vulnerability peering out from under rapturous lyrical onslaughts. As for his turn at the Folk Festival this year, “I definitely want this on the record,” Demeanor insists. “I’m so excited about my set. I think that this is going to be something that has never happened before, ever in America, ever. This is going to be one for the books for sure.”

I think he means it.