Follow the Money

Ben Franklin’s blueprint for America

By Stephen E. Smith

How is it possible that Ken Burns’ recent four-hour Ben Franklin documentary received ho-hum reviews? Have PBS devotees grown too familiar with Burns’ still-life voiceover production style? Maybe. But the lackluster reviews are more likely the fault of the kite-flying, bifocaled purveyor of the bon mot, old Ben Franklin himself. He’s every American’s everyman, the most human of our Founding Fathers.

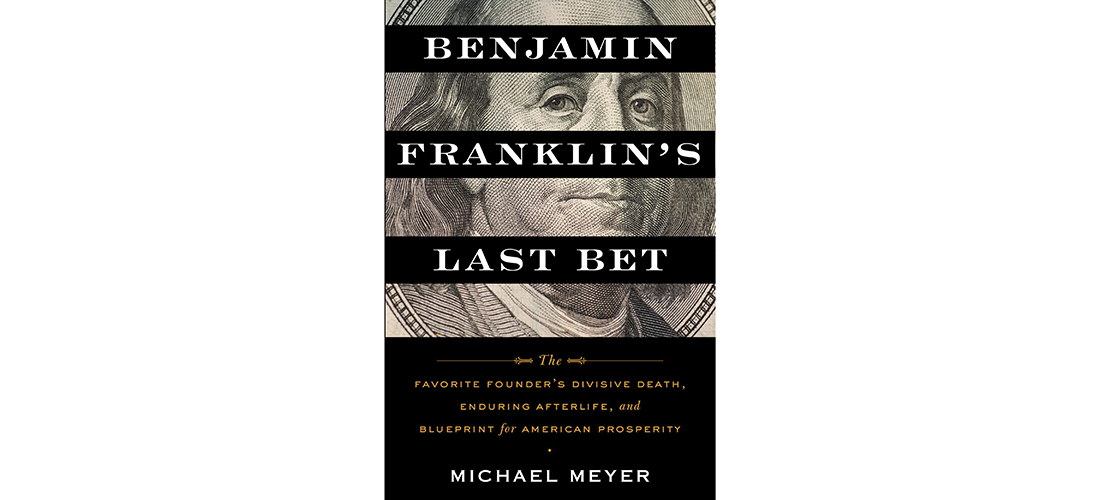

We grew up learning about Franklin, and most of us believe we know what needs to be known about the archetypal American Renaissance man. Historian Michael Meyer’s Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet: The Favorite Founder’s Divisive Death, Enduring Afterlife, and Blueprint for American Prosperity is a timely reminder that there is still much to learn about the influence Franklin continues to wield in 21st century America.

When he died in 1790 at the age of 84, Franklin was not universally mourned by his countrymen. Meyer reminds readers that George Washington and the Congress refused to acknowledge attempts by the French to express their condolences at Franklin’s passing, and John Adams had little good to say about his former diplomatic partner. Among his later detractors were Mark Twain, who wrote that Franklin “early prostituted his talents to the invention of maxims and aphorisms calculated to inflict suffering upon the rising generation of all subsequent ages”, and D.H. Lawrence reveled in revising and ridiculing Franklin’s 13 virtues.

Meyer’s primary focus is on the influence of Franklin’s last will and testament. William, Franklin’s first-born son who had sided with the British during the Revolution, was left worthless property and ephemera, and his daughter and grandchildren received gifts commensurate with the esteem in which he held them. But it was his “Codicil to Last Will and Testament,” a wordy but straightforward document, that morphed into a hydra-headed legal instrument that would vex administrators, the courts and politicians who attempted to oversee and control its ongoing disbursements.

Franklin established endowments for the cities of Philadelphia and Boston. “Having myself been bred to a manual art, printing, in my native town,” Franklin dictated, “and afterwards assisted to set up my business in Philadelphia by kind loans of money from two friends there, which was the foundation of my fortune, and of all the utility in life that may be ascribed to me, I wish to be useful even after my death, if possible, in forming and advancing other young men . . . .”

Franklin left each city £1,000, or about $133,000 in today’s dollars. The funds were intended to provide small loans to manual and industrial workers — cobblers, coopers, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, carpenters, etc. — to be repaid at 5 percent interest over a 10-year period. In addition to offering a helping hand for the socioeconomic class employed in manual labor, the funds’ underlying intention was to promote good citizenship. (“I have considered, that, among artisans, good apprentices are most likely to make good citizens,” Franklin wrote.) If the principal from the bequests were properly administered, the initial investment should have yielded billions in today’s dollars, making Franklin our first billionaire philanthropist.

So, what became of Franklin’s fortune, and where did his generosity lead us? Meyer follows the money, providing a decade-by-decade accounting of the funds’ expenditures while factoring in economic trends, poor oversight by fund managers, legal squabbles, political infighting, and losses incurred during national recessions and depressions.

All of which sounds incredibly boring. But be assured there’s nothing tedious about Meyer’s chronicle. What emerges is a lively and thoroughly researched social history of the country viewed through our evolving economic affluence and the increasingly litigious nature of American society.

The early ledgers read much like a personalized history of the country: “Turning the musty pages of each loan agreement can feel like reading an old swashbuckling story,” Meyer writes, “bringing the same sense of relief when the last line reveals that a character has made it through. Three cheers for the cabinetmaker Christopher Pigeon, who repaid his debt on time. And a compassionate wag of the head for Paul Revere’s son-in-law, one of only two Boston defaulters.”

Unfortunately, there was skullduggery aplenty in the management and disbursement of Franklin’s gifts. In 1838, Philadelphia’s Franklin Legacy treasurer John Thomason purchased Philadelphia Gas Works stock with Franklin’s bequest, thus impeding the money’s growth and transforming the fund into a tool of corruption and patronage. In 1890, Franklin’s descendants were so aggrieved they felt compelled to file a suit claiming that his bequests should revert to their control.

Boston did not suffer a similar level of financial chicanery. In 1827, William Minot, who administered the fund for 50 years, deposited much of Franklin’s principal into Nathaniel Bowditch’s Massachusetts Hospital Life Insurance Company to acquire interest, thus enabling Boston’s fund balance to surpass Philadelphia’s for the first time. Beantown never trailed again.

In the final analysis, Franklin’s bequests accomplished very little of their original intent. In the days before central banking, loans were difficult to administer in an equitable manner, and many of the later loans suffered default or were not repaid on time. By 1882, Philadelphia had only about $10,000 left in its fund. Franklin had failed to factor in even a single default, and he had no way of foretelling the emergence of liberal credit terms and the growing availability of loans charging less than 5 percent interest. In 1994, the entirety of Boston’s Franklin fund went to the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology. The Philadelphia Foundation continues to manage its Franklin Trust Funds for its original purpose.

At this moment of intense political division and national soul searching, Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet is a timely reminder that we remain a generous people, and that philanthropy lives on in the hearts of ordinary Americans. The popularity of GoFundMe pages is the latest manifestation of our desire to help those in need, an example of the civic-mindedness exercised by the “good citizens” Franklin hoped to encourage. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.