Innovative Aussie gardner, Stephen Johnson, makes

his mark on Greensboro’s Lindley Park neighborhood

Next objective: The City at large

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Lynn Donovan

If Stephen Johnson’s Australian accent didn’t give away his homeland, his Aussie-made Akubra hat might.

If Stephen Johnson’s Australian accent didn’t give away his homeland, his Aussie-made Akubra hat might.

It’s a floppy felt lid made from the soft undercoat of rabbit fur. Light and waterproof, the hat keeps Johnson cool in the summer and warm in the winter, which is important when you spend as much time outdoors as he does.

He’s a farmer, but not just any old MacDonald.

He’s an urban farmer.

Unlike hobby growers, he aims to turn a profit with his herbs, greens and vegetables. At least, that’s the idea.

“The last two quarters, I broke even,” says Johnson, 52, who started urban farming full-time in 2013. “I’m still experimenting.”

As far as Johnson knows, he’s the only farmer inside the Greensboro city limits.

His spread? About three-quarters of an acre behind the 1914 bungalow he shares with his wife Marnie Thompson, on South Elam Avenue.

The yards in their Lindley Park neighborhood are vast.

“I have a land map from 1937 that shows this land was zoned agricultural,” says Johnson. “Most of these houses were here. The guy who developed this neighborhood was a contemporary of Olmsted.”

Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of landscape architecture in the United States, is most famous for designing New York City’s Central Park. Lindley Park echoes that pastoral feeling. Johnson recalls a Boy Scout troop trekking through his backyard once.

“They said, ‘Wow, we didn’t realize there was a city park back here.’”

True to the neighborhood’s agricultural roots, Farmer Johnson can be found on most Saturday mornings at The Corner Farmers Market, an assembly of 20 or so local vendors who pool, year round, in the parking lot of Sticks & Stones, a pizzeria up the street from Johnson’s house.

“He’s really a mentor to everybody here,” says market coordinator Kathy Newsom. “If somebody says, ‘Wow, I only sold $10 today,’ he’ll say, ‘Well, let’s go look at your booth.’ He’s able to do it in such a gentle way that it doesn’t feel like he’s telling you what to do. There’s no finger-wagging.”

At market, Johnson sets up wherever there’s room, under a canopy with a small sign that says Elam Gardens. He sells fresh seasonal produce — mostly greens and herbs. If he grows too many fruits and vegetables for his personal use, they appear at market, too.

This commerce-over-coffee accounts for half of Johnson’s green.

The other half comes from selling to restaurants in the same area, the so-called Four Corners at the intersection of Elam and Walker avenues.

Sticks & Stones Clay Oven Pizza; Fishbones; Lindley Park Filling Station; Reto’s Kitchen — all of them buy just-picked herbs, salad greens and heirloom tomatoes from Johnson’s plot, the closest they can get to having their own kitchen gardens.

Johnson switched to farming after a working for more than 20 years as a psychologist, first in public schools and later for companies that developed assessment and certification tools for various industries.

“It was interesting,” he reflects. “But when you retire, and sit down, will it have made sense?”

Johnson answered his own question by leaving his job four years ago and doing what made more sense to him: growing produce.

“I’ve always grown things, ever since I was 7 years old,” he says. “My first set of plants was a strawberry patch outside the front door.”

That was in the city of Perth, on the western edge of Australia.

His strawberries bloomed, but Johnson harvested no fruit.

“One day, I came home to see a big, blue-tongued skink,” he says, naming the berry-loving lizard.

Johnson learned the first lesson of growing: “Plant more than you need, because you’re going to lose some.”

Another memory of his youth: going to market.

“On the weekends, you went to market to get all sorts of stuff: toys, books, clothes, food,” he says. “It used to be run by mostly immigrants — Chinese or Greek or Italian or Vietnamese.”

Johnson carried the experience with him when he became an immigrant.

In 1995, he visited Greensboro, half a globe away from his hometown, to follow his Ph.D. adviser to UNCG. He found more than scholarly advice. “I came back in late 1996 so that Marnie and I could be on the same continent,” he says.

When their neighbor, restaurateur Neil Reitzel — he owns Sticks & Stones and Fishbones — proposed creating The Corner Market in Lindley Park four years ago, Johnson latched on to the idea quickly.

“My original plan was I’d build a little market cart and go sell on the weekends,” he says, laughing.

His plan mushroomed into a new career.

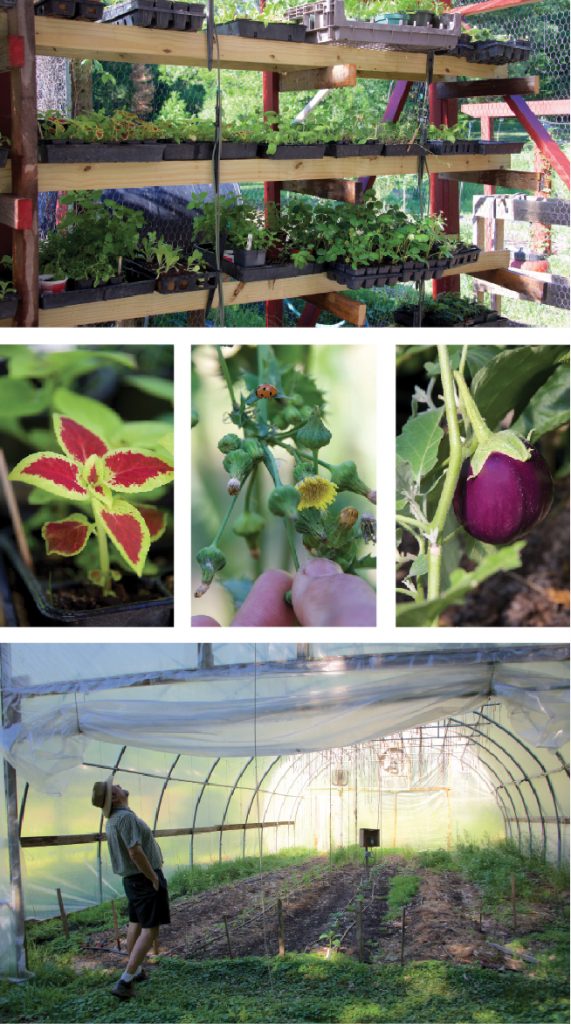

Johnson bought an old diesel tractor and a 50-foot-long hoop house, where he grows his main cash crops: arugula, parsley, basil, peppers, eggplant and tomatoes — which become toe-MAH-toes under the influence of his accent.

Outside the hoop house, where it’s cooler, Johnson grows an assortment of lettuces for restaurants, along with vegetables and herbs for personal use. Basil is a staple.

“I make a mean cashew pesto,” he says.

He experiments with different crops in a back corner of the yard. Last year, he tested carrots, potatoes and oats. This summer, he tinkered with okra, and got better results.

Nothing goes to waste, be it produce or experience. If crops succeed, they go straight to table or market. If not, they — and the weeds — go to the chickens that Johnson tends, on his property, with a neighbor.

Nothing goes to waste, be it produce or experience. If crops succeed, they go straight to table or market. If not, they — and the weeds — go to the chickens that Johnson tends, on his property, with a neighbor.

Another neighbor minds the bee boxes along the drainage ditch that bisects the yard.

“I get the benefit,” says Johnson, a smile flowering at the center of his salt-and-pepper beard. “I get honey.”

For several years, he’s been working to improve the ditch, and the quality of the water that flows through it, by flattening the banks and planting them with willows, blackberries, elderberries, sedges and other grasses.

The plants slow down and filter the storm water that passes through his yard.

“I’m trying to think not just of my needs but my community’s needs,” he says.

To those ends, he and Thompson — she co-manages the nonprofit Fund for Democratic Communities — have installed a 10-by-30-foot solar panel in the middle of their backyard. By capturing the sun’s energy, they meet most of their home’s daytime electrical needs.

“We’re going through the process of getting a system for solar hot water,” says Johnson.

The couple’s appetite for Earth-friendly ways of living extends to the wood stove that heats their home and to the system that catches rain from their home’s metal roof and funnels it to barrels and a 1,500-gallon cistern. They use the water for irrigating plants, including their front-yard fruit trees.

Johnson eyes more improvements. Next to the chicken run, he’s building a fish farm/aquaponics operation. He has introduced bluegill, bass and crappie to two plastic vats filled with water and equipped with aerators. The water, fertilized with fish waste, will circulate to zip-grow towers — essentially square vinyl post covers with a slit down one side.

In theory, lettuces and other greens will sprout in a soil-free matrix.

The idea of growing food in vertical spaces intrigues Johnson.

“There are places in the world — like Singapore and Hong Kong — where they are building multistory grow towers on the line of skyscrapers,” he says.

Earlier this summer, more vertical experiments dangled nearby. Johnson drilled out fat plastic tubes, plugged them with strawberry plants, and hung them, like living wind chimes, from a wooden frame.

He painted the tubes red and green to study the effect of different colored reflected light on the timing and duration of strawberry blossoms.

Fellow farmers will recognize his trial-and-error approach to growing.

“There’s that old thing that most farmers are country bumpkins — well, no,” says Johnson. “To have a successful growing operation, you can’t be switched off to technology that’s coming down the pike.”

Johnson hopes to spark more interest in urban, and suburban, farming.

“Greensboro could feed itself — with all of its protein and vegetable and most of its fruit needs — without a doubt in my mind,” he says. “We get as much sunlight as Cyprus; we’re on the same latitude.”

His blue eyes flash at the thought that so little of Greensboro’s food is

grown locally.

The know-how is here, he says. He sings the praises of N.C. A&T State University’s urban horticulture program, which has supplied him with advice and physical assistance for his USDA-registered farm.

“There was an intern there that had worked on a strawberry farm,” he says. “We built the strawberry towers together.”

John Ivey, an agent in the Guilford County office of the N.C. Cooperative Extension, helped Johnson with crop selection and marketing.

The Carolina Farm Stewards Association, based in Pittsboro, schooled Johnson on the best uses of his hoop house.

Given the readily available knowledge, Johnson is flabbergasted that Greensboro is so dependent on food grown elsewhere.

“We could develop a resilient food system, and put people to work and do it sustainably — financially and environmentally,” he says. “It’s achievable, but it requires a different mindset and support system.”

He sees opportunity even in the developed parts of town.

“There’s so much empty commercial real estate in this city,” he says. “Why aren’t we rethinking the use of existing commercial properties for hydroponics or food production?” he says.

It’s nutty, he says, that an Aussie transplant should be at the fore of urban farming here. “I should be following people in North Carolina,” he says.

Newsom, the farmers’ market coordinator, says Johnson doesn’t give himself enough credit. She’s watched him work at the market and at meetings of

the Lindley Park Neighborhood Association, which he heads.

“He can lead without looking like he’s leading,” she says. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry.

Want to Go?

As a part of Local Foods Week, the N.C. Cooperative Extension will host a tour and talk at Stephen Johnson’s home on Thursday, September 28, starting at 5:30 p.m. Johnson and kitchen managers will discuss the advantages of using locally grown food. The talk and tour will be followed by dinner at a nearby restaurant. The audience will be limited. Register by going to guilford.ces.ncsu.edu and looking for “local foods.”