Short Stories

Lovin’ Some Lyle

Singer-songwriter-actor Lyle Lovett brings his witty lyrics and distinctive spin on country music to the Steven Tanger Center for the Performing Arts on Tuesday, March 8 at 7:30 p.m. Accompanied by an acoustic band, the four-time Grammy-Award winner hit the road at the beginning of March — the first time in two years. The show will feature acoustic arrangements of Lovett standards, as well as a preview of songs from his upcoming album, scheduled for release in May. The smaller ensemble and Lovett’s informal, conversational onstage style will provide the audience with an up-close, “living-room” listening experience. Rumor has it that the Texan lives near Houston in a house built by his grandfather in 1911. Explains a bit about the diversity of his music. Info: TangerCenter.com

Fun and Names

The Greensboro Children’s Museum is upping its game for kids of all ages. In January, it received its largest donation in its 23-year history. The $1.25 million donation from Frank and Nancy Brenner will be used to advance the museum’s mission to inspire hands-on learning through play, as well as fund building repairs and upgrades to more than 20 indoor and outdoor exhibits. The gift officially launched the museum’s capital campaign, “Building for Tomorrow,” to raise $2 million for infrastructure improvements to the facility. In honor of the gift and recognition of the museum’s expanded presence throughout North Carolina and Virginia, in July the museum will be renamed the Miriam P. Brenner Children’s Museum. Miriam Brenner is the late mother of Frank Brenner. Info: GCMuseum.com

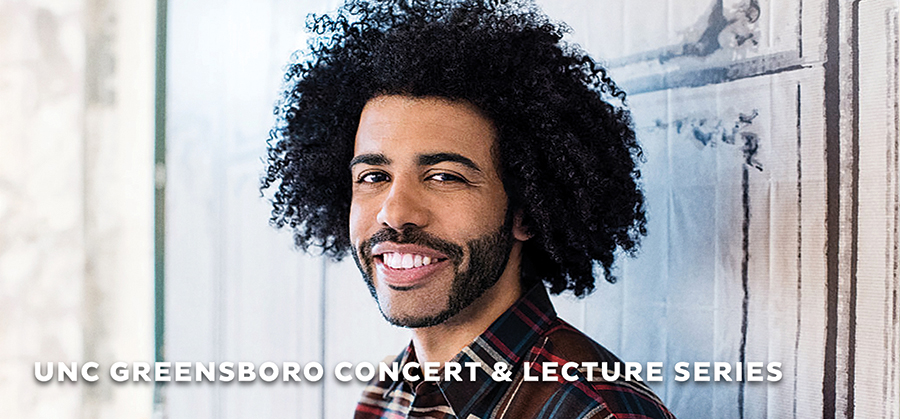

As Seen in O.Hey

Don’t throw away your shot to hear a phenomenal entertainer speak and perform as part of UNCG’s Concert & Lecture Series. Daveed Diggs is an actor, rapper, singer-songwriter, screenwriter and producer known for his work in Hamilton, Black-ish, Snowpiercer and Disney’s forthcoming The Little Mermaid — we hear he’s a little crabby about that. Catch Diggs at 8 p.m. on March 5. Info: VPA.UNCG.edu/ucls-2; to subscribe to O.Hey, visit oheygreensboro.com

A Fairy Tale Come True

Cinderella — the time-honored, beloved story of a dreamer — shunned by her step-monsters and saved by a fairy godmother, glass slippers, industrious mice and a charming prince — comes to life at the Carolina Theatre, 5 p.m., Saturday, March 26 and, 3 p.m., Sunday, March 27. The classical ballet version of the Brothers Grimm fairy tale brings drama, romance and humor to the stage — not to mention outstanding performances by the Greensboro Ballet. Set to the music of Sergei Prokofiev, the ballet will remind you that dreams can come true. And sometimes losing a shoe isn’t a bad thing. Young Cinderellas in training can dress in their favorite princess costume and enjoy a tea party with Cinderella and her friends. Included will be a goody bag and a princess craft project. Meet many of the characters from the ballet and, of course, the Cinderella herself will pose for photos and give autographs. Definitely a sugary sweet event for sugary sweet sweeties. Info: CarolinaTheatre.com/Events

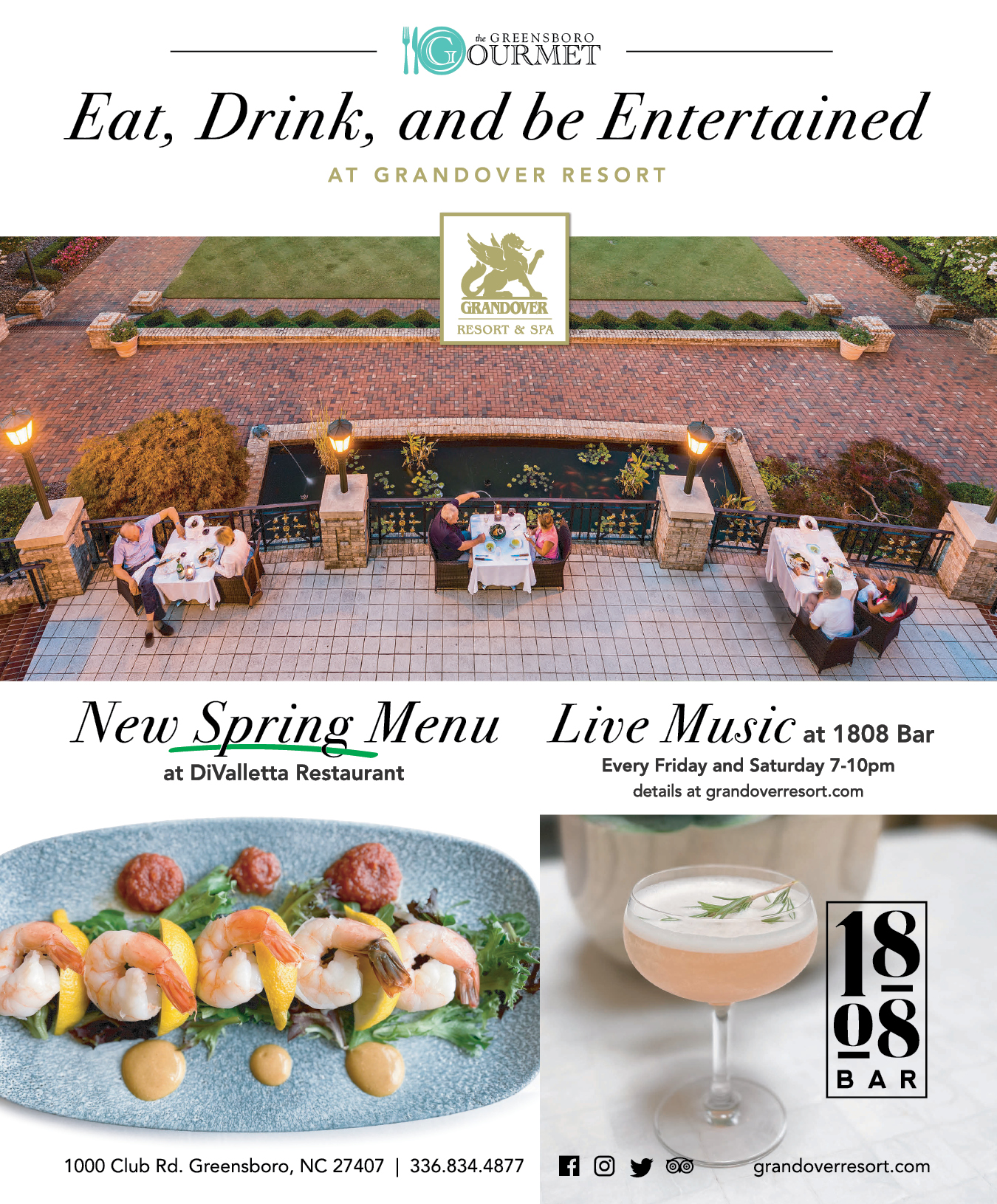

Dynamic Duo

While we’re on the subject of 24-carat entertainment, chanteuse extraordinaire Jessica Mashburn, along with world-renowned singer/songwriter /devoted husband (because why wouldn’t you be?!?) Evan Olson, are once again performing as AM rOdeO. They will bring their merry melodies to Grandover Resort’s 1808 Lobby Bar from 7–10 p.m. on Friday, March 11. Two of the most talented performers you’ve ever heard of, AM rOdeO reminds O.Henry’s me of big city lounge entertainment. Practically a lost art, Jessica and Evan bring with them a wide repertoire of tunes from The American Songbook classics to the present. Evan Olson’s musical compositions recently have been featured on network shows such as The Young and the Restless, America’s Funniest Home Videos and Dexter: New Blood on Showtime. This promises to be a sophisticated, enormously entertaining kick-off to your weekend. Info: GrandoverResort.com — Billy Eye

Ogi Sez

by Ogi Overman

Let’s pause for a moment and reflect on the past two years — how we handled the horrors, the isolation, the fear of the unknown, the suffering that began not one but two Marches ago. Many of us were on the brink of losing all hope, and, maybe, some of us did. But then came that sliver of light at the end of the long, dark tunnel, and now we hope that we will find ourselves at the dawn of a new day, a new season, a new and vastly different March.

Let the music play.

• March 19, Greensboro Coliseum: Women’s basketball takes center stage at the Coliseum this month, but nestled between the ACC tourney and the Regionals, the Avett Brothers managed to sneak in their rescheduled New Year’s Eve show. They promised they’d be back and they didn’t disappoint. But then, they never do.

• March 25, High Point Theatre: The mid-’90s were marked by a resurgence of swing music, led on the East Coast by the Squirrel Nut Zippers and the West Coast by Big Voodoo Daddy. But the phenomenon also was going on in Great Britain, with the Jive Aces leading the charge. They’re bringing their “Jump, Jive & Wail” tour stateside this spring, and I think I’ll Zoot up and flip, flop & fly over to High Point.

• March 26, Ramkat: It seems almost cliché to call Donna the Buffalo a cult band. Granted, a quarter century ago they amassed an immediate cult following that has only multiplied today. But by taking a leap of faith and forming the Shakori Hills GrassRoots Festival down the road in Pittsboro, they took on an aura all their own. So, if you can’t wait until May to see them, head over to Winston.

• April 1, Ziggy’s: I know, I know, I’m breaking the rules by hyping a date in April, but, as Barney said when the gold truck came through Mayberry, “Ange, this is big. This is big — big!” Indeed it is. When a legendary music venue reopens in a new town and is again run by a venerated impresario, Jay Stephens, it deserves a month’s notice. Ever-popular newgrass act Acoustic Syndicate hosts the grand opening. And it promises to be grand.