A veteran pays homage to those who went before

By Colonel Charles A. Jones, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (Retired)

Some people, such as Morris Whitfield, have an address known only by their first and last names.

But, in fact, his address has additional information: Section One, Number 88.

Morris Whitfield resides — really, rests — at that address, which is a grave in the Veteran’s Circle of Greensboro’s Forest Lawn Cemetery.

I first learned about Morris Whitfield after my 1995 visit to Iwo Jima, the Pacific Island that was the site of perhaps the most famous battle in Marine Corps history. Marines became famous for twice raising American flags atop Iwo’s Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945, during World War II. The second flag raising was the subject of the photograph that won Joe Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize for Photography. His iconic photograph is one of the most famous in the history of warfare.

But unlike many Marines and their Navy corpsman who saw the flags atop the mountain, Morris Whitfield missed the event because, like so many of Iwo Jima’s casualties, he was already dead.

After my return from Iwo Jima, which the United States returned to Japan in 1968, my parents and I visited the Veteran’s Circle of Forest Lawn Cemetery for no particular reason. By chance I spotted the Whitfield tombstone and, being a Marine myself, gravitated to it when I read part of its inscription: “PVT US MARINE CORPS,” with “PVT” representing Private, the lowest grade in the Marine Corps. Having been to Iwo Jima, I knew immediately the importance of his date of death: “FEBRUARY 19 1945,” D-Day for Iwo Jima, the date the Marines and their Navy corpsmen landed on the island to capture it from the Japanese.

The sadness is twofold: first, his death itself, and second, his death so soon — the very day he came ashore.

When I worked at the United States Marine Corps History Division, I obtained the casualty report for Morris Whitfield (“casrep” in typical military expression). From the casrep I learned that he was a member of the 31st Replacement Draft, an organization comprising Marines in a rear area where they remained until one or more of them were sent forward when needed in frontline units, engaged in combat, to replace Marines who had been killed or who were wounded and evacuated.

The casrep reported the cause of death as “GSW mult lower extremities.” Translation: multiple gunshot wounds hit his lower extremities.

Morris Whitfield was buried on Iwo Jima with the remainder of his fallen Marine Corps and Navy comrades, but authorities decided after the war that none of our war dead would be left in what was former enemy territory. Thus began grueling, ghastly mass exhumations, and returns of the remains of our dead buried on Iwo Jima, and their transfer to the United States for burial in a national or private cemetery of the family’s choice. Since his widow had remarried, Morris Whitfield’s father requested in 1948 that his son be buried in Forest Lawn.

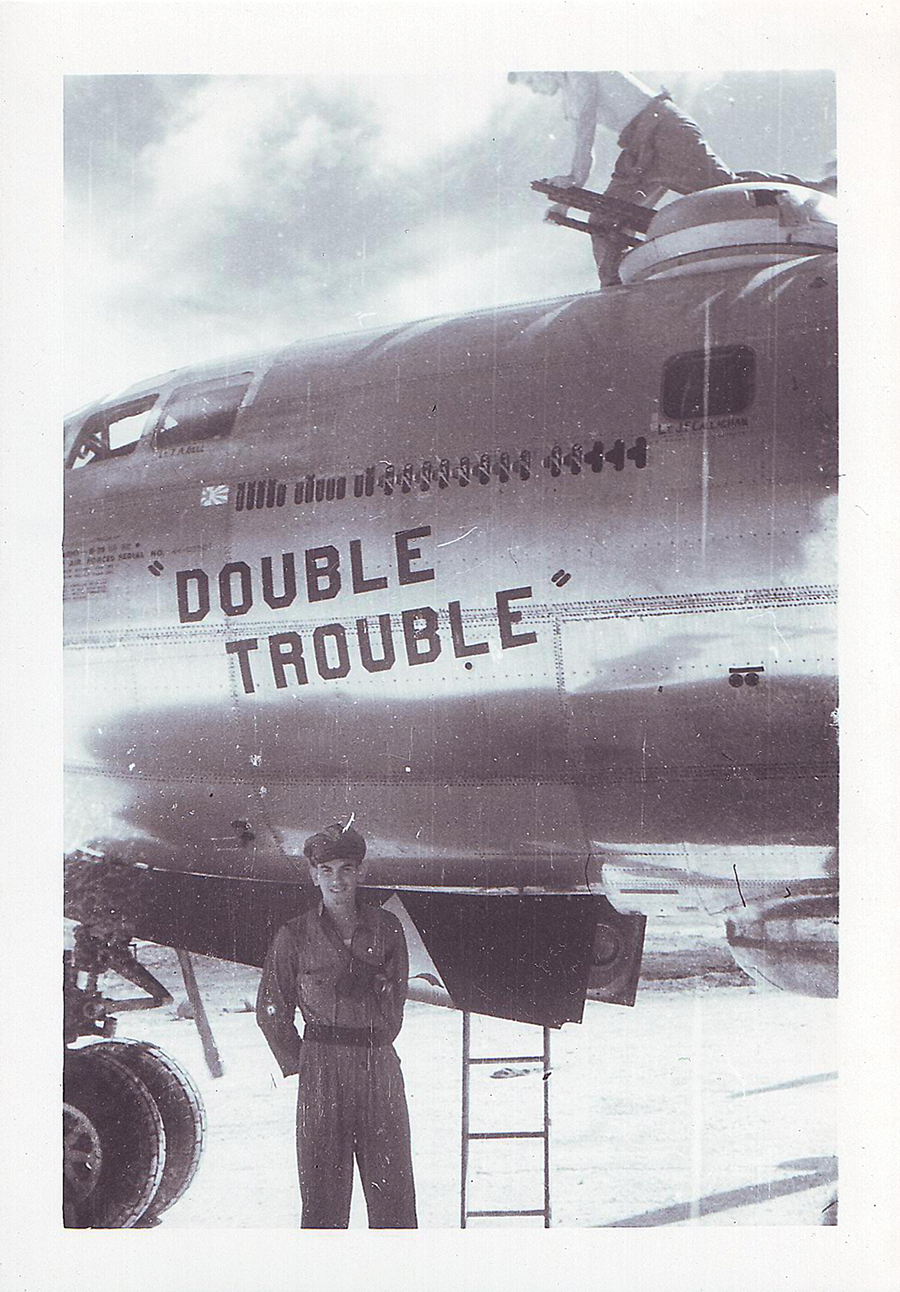

But Morris Whitfield is more than a burial for me — he and his tombstone are a reminder of what may have happened to my own father, a Glenwood “boy” who was the radar operator on a B-29 Superfortress bomber with 28 combat missions over Japan: 13 bombing missions and 15 photoreconnaissance missions. The crew named the B-29 “Double Trouble” and “City of Maywood.”

After he died in 2014, I found among his effects a handout titled “Memorial Day Program.” Obviously, his mother (my grandmother) sent it to my father during the war or gave it to him after he returned from the Pacific War.

The program was for a Memorial Day ceremony on Sunday, May 27, 1945, at Forest Lawn to honor war dead who were listed under the title, “Roll of Honor.” Under that title was “Names Added Since Last Memorial Day,” a testament to the nonstop killing occurring during World War II and the need to honor the dead, from both Greensboro and rural Guilford county, lost during each year of the war.

The program reflected our then-segregated society, so under the heading “World War II” was a section with the names of Greensboro “White” men. Below that list was a section with the names of Greensboro “Colored” men. The rural section followed suit: Below the list for Guilford County “White” men was a list of Guilford County “Colored” men.

The name of Greensboro’s most famous airman, “Preddy, George Earle, Jr.,” was on the list of dead since he was killed by “friendly fire” on Christmas Day 1944. To this day, he remains the pilot with the most kills while flying a P-51 Mustang fighter and is the number six ace among all United States Air Forces aces (although he was, like my father, a member of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II since the Air Force was not separate from the Army until 1947).

The sadness is in my grandmother’s markings on the program. She placed 11 “X” marks beside the names of “boys” she knew who were lost during World War II. And on the front she wrote a note to my father: “You may know some of these boys on here — I do.”

Under the heading “Rural Guilford County — White” was a familiar name: “Whitfield, M. E.”

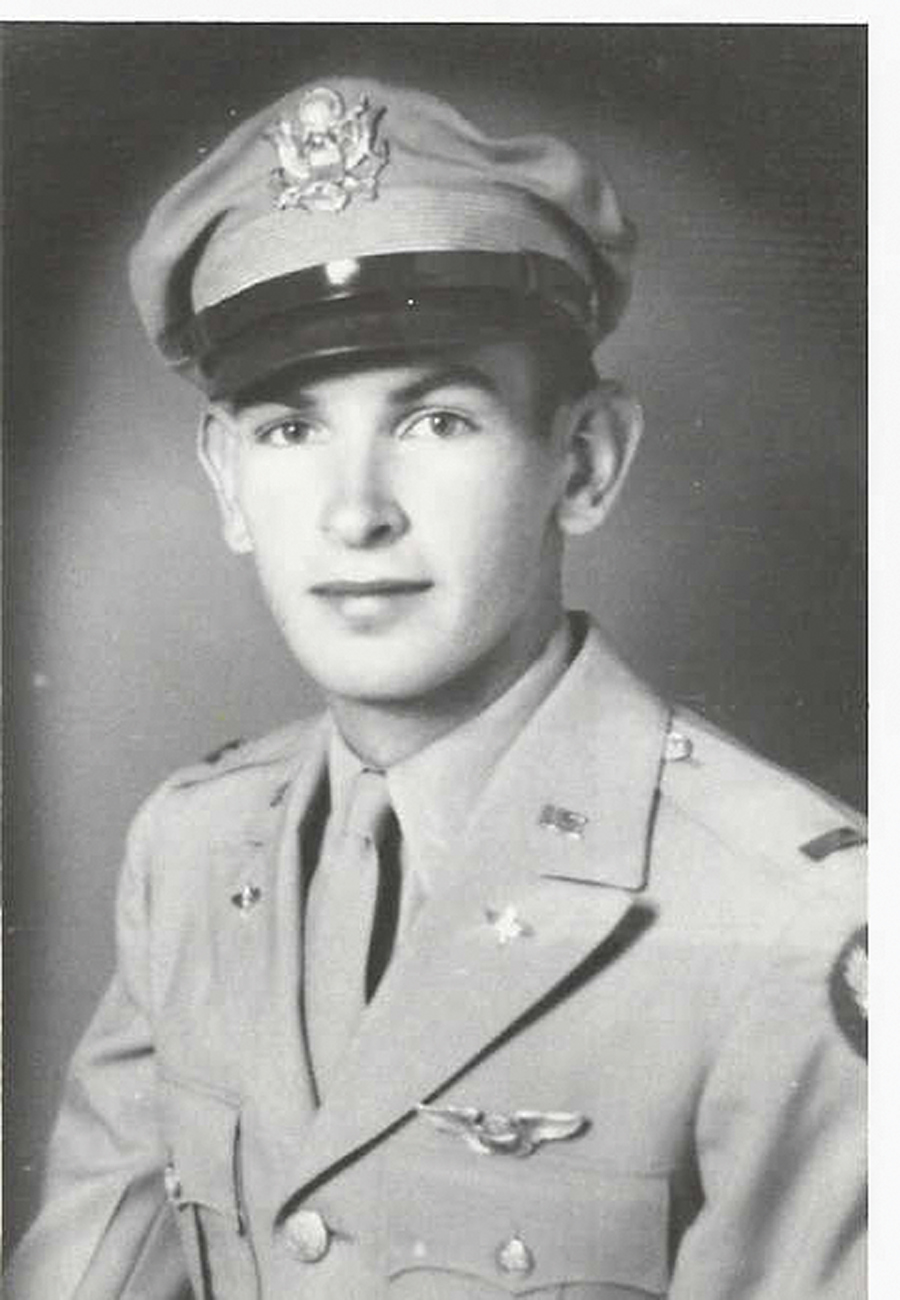

Left: Lt. Elmer Jones, 1994.

Middle: Lt. Elmer Jones below the the left nose of the B-29 Superfortress.

Right: Crew of the B-29 kneeling with six enlisted men standing behind them. Lt. Elmer Jones is kneeling second to the left.

My father has three connections to Morris Whitfield.

First, his B-29 had to land on Iwo Jima twice during the war, once for fuel and once for repair. Had the Marines and their Navy Corpsmen not captured the island, my father may have had to parachute into the Pacific Ocean, an irony since he flew so many times over the Pacific but could not swim. Or his B-29 may have ditched in the ocean, an unpleasant and dangerous action at best.

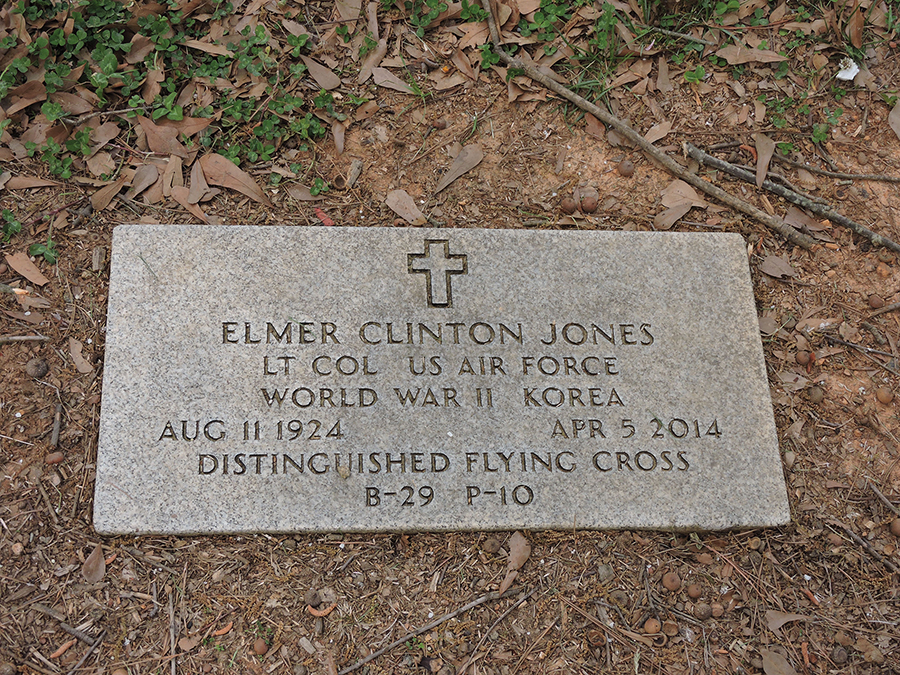

Second, my father is buried near Morris Whitfield. Each December, the Wreaths Across America program places wreaths on veteran graves in veteran sections of cemeteries. I attended in 2019 and 2021, and each time I “appropriated” two wreaths before the speaker stopped speaking so I could be the person placing a wreath against Morris Whitfield’s tombstone and one on my own father’s footstone — since he is outside the veterans section, he would not have received a wreath but for my determination that he have one.

Third, and most importantly, my father survived the war for four reasons. His aircraft commander was a superb pilot. My father was adamant that the number of photoreconnaissance missions saved his crew since they were “single ship” missions, meaning the plane flew the mission alone; the Japanese would not shoot at a solo B-29 to keep from disclosing their antiaircraft gun locations. Another reason was luck. And the final reason was Iwo Jima: Had Marines and Navy Corpsmen not captured Iwo Jima so it could be a place for bombers to make emergency landings, my father may have perished in the ocean.

So what was most important was that my father’s name was not on the list of the dead for deaths up to Memorial Day 1945. But it could have been: From April 1945 to Memorial Day 1945, he was flying combat missions over Japan in his B-29.

If my father were killed or missing after Memorial Day 1945, his mother may have found herself at Forest Lawn in 1946 on Memorial Day with a sad updated program — one with the name of her son under “World War II — Greensboro White.” And this story would never have been written.

Combat death is callous, stripping almost all personal attributes from what had once been a living, breathing combatant who had an address, friends and family. Remaining is a casrep with the typed ominous acronym, “KIA” (killed in action) — a notation I thank God was not typed besides my father’s name. Also remaining is the title, “hero,” reserved for men like Morris Whitfield who did not return and were — and still are — left with only a few brief etchings on a tombstone.

Thus the address remains the same and always will — simply “MORRIS E WHITFIELD.” And that address is timeless: Morris Whitfield will never move. He will not be departing Forest Lawn Cemetery temporarily or permanently. I had to travel thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean to reach and to visit Iwo Jima to learn the importance of the date that placed and keeps him in Section 1, Number 88. OH

Colonel Charles A. Jones, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, served as a judge advocate (military lawyer) in the Regular and Reserve Marine Corps for a combination of 30 years (1981 to 2011). He enjoys his major passion: researching and writing military history. He wrote a biography of his father focusing on his World War Two experiences: B-29 “Double Trouble” is “Mister Bee” (available on Amazon). His email is cajonesdt@gmail.com.