What constitutes a home library varies from one book lover to another

By Cynthia Adams

Imagine a library with 51,000 books towering two stories to the ceiling, amassed by Johns Hopkins professor Richard Macksey. Though Amazon’s Kindle debuted 15 years ago, print survives. Writer/actor Stephen Fry declared in 2013, “Books are no more threatened by Kindle than stairs by elevators.”

In January, The New York Times released a photo of the late Macksey’s dream library, which included extraordinarily rare editions. The image was retweeted nearly 40,000 times in a mere month. Although the library was dismanted after Macksey’s death in 2019, the Baltimore bibliophile, a towering intellect, curated a stunning dreamscape of books reaching two stories in height, with the surreality of a movie set.

Macksey was book wrapt — i.e. enchanted by his own home library.

George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore library contained 20,000 books, many of them first editions. When eight graders are taught North Carolina history, field trips to Biltmore Estate provide a breathtaking example of what it means to be book wrapt and want to assemble a library.

Gen Z and Millennial readers, whose affection for printed books mirrors screen-time fatigue, still dream of such a place. A real library, it is variously estimated, requires 1,000 titles — or 500 — or fewer. With the advent of e-books and so many people downsizing their homes, a small assembly of treasured volumes, artfully displayed, is very much a library.

On these pages you find a number of book-wrapt Triad readers who have created personal libraries with varying numbers of titles and configurations — the largest of them symbolically filled with family heirlooms, like a Victorian cabinet of curiosities — yet all of them inspire.

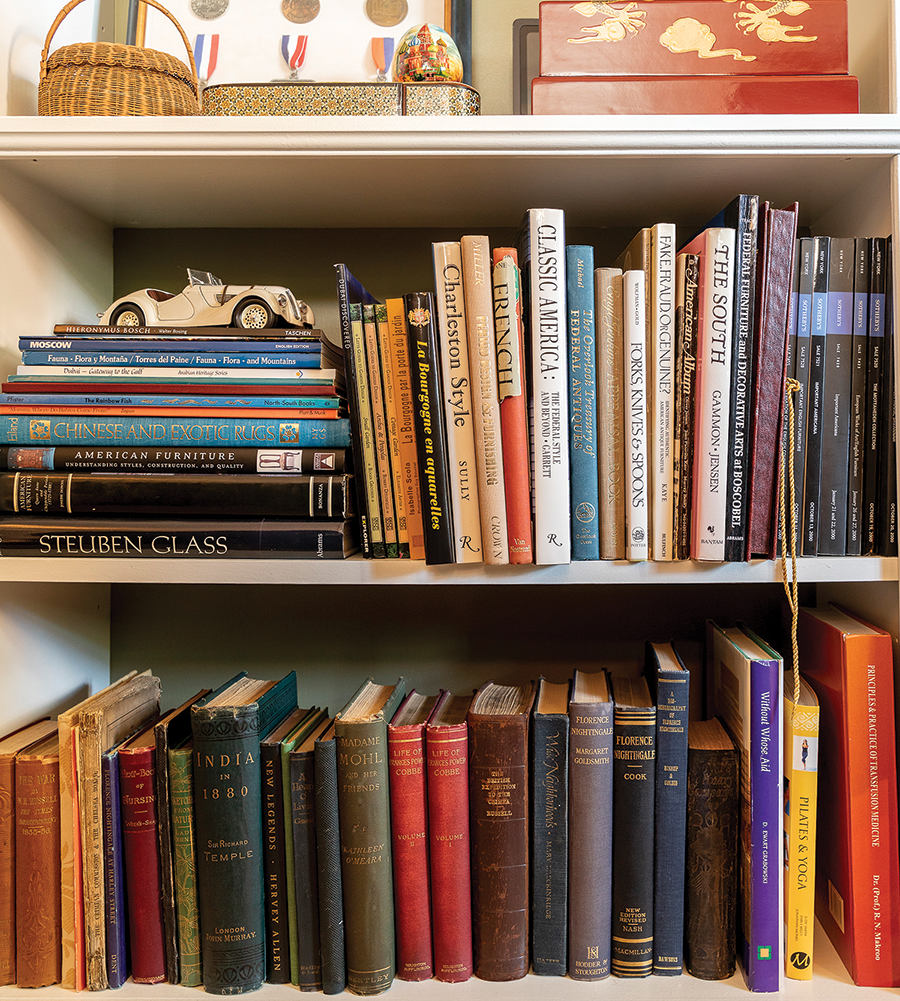

Sharon James is snugly book-wrapt in her Stoney Creek study/library. She is surrounded by artwork, collectibles and books as she works from home for a company that conducts international hospital inspections.

Here, she spends hours. Her husband, Tom, a High Point University economics professor, keeps a desk nearby.

“I love the warmth of books!” Sharon James says. “I have them lying around in every room. I love leather-bound books, the richness of their color, and I often wonder what prompts someone to write what they do.” Countless other volumes spill into the downstairs. Like many book collectors, James recently undertook a purge to make way for more. This led to a discovery that some favorite titles were duplicates. Lucky friends inherited those.

“I have always had to have bookshelves in my homes,” James says. “If there were none, then I had them built as I did here. Nothing is more relaxing to me than sitting in my favorite French chair, with a good book and a glass of wine. And once I start reading and am into it deeply, I hate being disturbed!”

A former nurse, James enjoys “biographies about women who do great things,” prizing a first edition of Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing. She is an avid collector of English and American antiques, so amasses books on the decorative arts.

This is a common thread among bookies: Private passions are revealed in their private libraries.

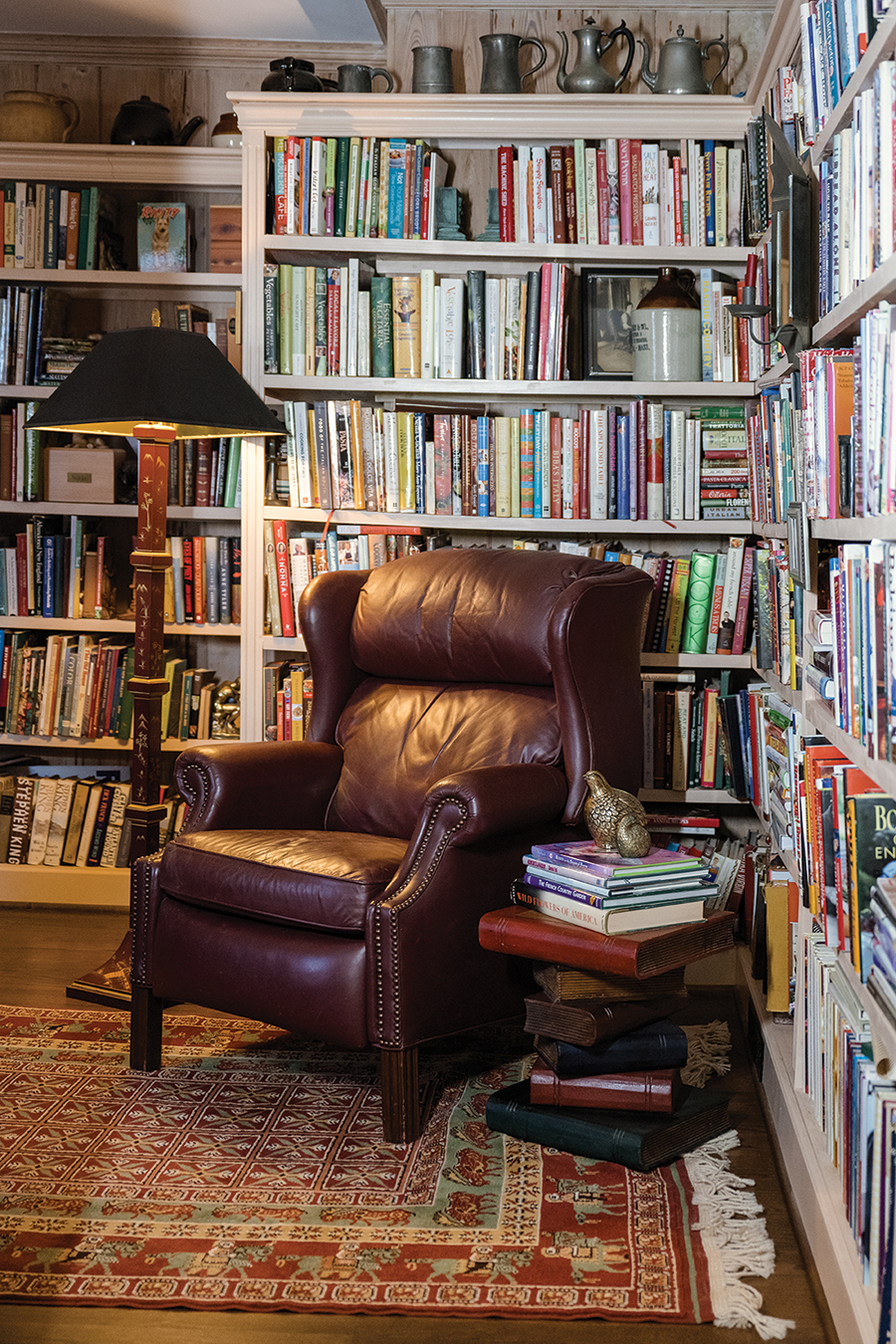

Recent New York transplants Rick and Randy Burge-Willis own approximately 1,500 to 2,000 volumes and remodeled to accommodate the excess. (See March 2022 O.Henry: www.ohenrymag.com/a-leap-of-faith.)

“There were existing bookshelves in the living room, but our previous home had a ‘main’ library and a ‘kitchen’ library. When we moved here, we only had enough space for about a quarter of our books. It seemed natural to turn our large office space into a library, so we had half of the walls lined with bookshelves.”

They were careful to maintain the original pecky cypress paneling. “We also wanted to mirror the classic moldings and trims of the rest of the house.”

Cookbooks comprise the former restaurant owners’ largest collection, “from church cookbooks to James Beard – award winners, including every edition of the Southern Living Annual Cookbook since 1979.”

Ashley Culler’s Emerywood home library literally rose from the ashes. It is a pastiche of past and present — a mini-Biltmore, but she says their previous library was far grander.

Leather-bound volumes collected for decades burned in a fire that ravaged the entirety of High Point’s Shadowlawn, a French Revival Tudor, in a Gothic style straight out of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. No personal images of the architecturally significant 1926 house survived.

Their current home is a smaller version, one that stood mere yards away. It is a beautiful echo of Shadowlawn, destroyed in 2010 by a Christmas fire. (See December 2016 O.Henry: www.ohenrymag.com/out-of-the-shadow-of-shadowlawn.)

The Cullers bought the carriage house that lay in its shadow, renovated decades earlier by Harold and Peg Amos. Over two years, the Cullers incorporated a few pieces from the ruins; stone from fireplaces, a few leaded glass windows, and a salvageable rear entry, and made it their own. (The Amoses had sold them Shadowlawn, as well.)

The “new” library built by the Amoses in the converted carriage house, as I wrote then, “most demonstrates the fineness of rooms in the lost house.” A paneled library, complete with a soaring, beamed ceiling, plaster friezes, marble fireplace, leaded windows, spiral staircase and balcony, is the Cullers’ “favorite room.”

Hundreds of collected leather-bound books in the Cullers’ former library were destroyed, along with family pictures, memorabilia and all but a few salvaged items — including a sword from Braxton Culler’s time at military school.

“He said to me, ‘I wish I had my sword back.’ So, one day I went through the ashes and the rubble, and I found it,” says Culler, who took the blackened sword to a local jeweler for cleaning and polishing.

“I surprised Braxton with that, giving it to him a year later.”

It again hangs by the fireplace.

Now, their library features inherited, irreplaceable family items: a “worry” chair possibly bought in the Far East by Jack Rochelle, Ashley’s father, and a cock-fighting chair that was possibly reproduced by Globe Furniture, where he was president; an opium pipe from Burma; solid mahogany elephants that Braxton Culler acquired in Honduras; a bust of Rochelle by his niece, Kitty Montgomery, wearing his top hat from the Sedgefield Hunt.

But the most prized of all is a handmade chess table made for Rochelle and presented by Globe artisans on Christmas Eve in 1952. Here she now plays chess with her grandchild.

“Braxton’s daddy’s dog tags from the war,” are on the mantle, Culler says. At last, new photos from their parents, fill the room. It’s become a repository of memories.

The fire’s hidden blessing is this, Culler says: “We are able to incorporate treasured heirlooms into our newer home.”

Like Culler, many book lovers experienced a library lost.

They discussed how downsizing forces more attrition, less accretion.

Retired Greensboro anthropologist Tom Fitzgerald now raids Little Free Libraries while out on walks in Sunset Hills, returning later to donate. He reads extensively, but no longer stocks a personal library.

Attorney Charles Younce, lover of biographies, history and fiction, keeps stacks of books by his bed — but, he says regretfully, no library. He is winnowing out possessions, something he counsels friends to do.

Former Greensboro librarian Pam Norwood and her husband, Phil, downsized a library of 2,000 books when they retired. They culled in earnest. “We kept about 200 books,” she estimates. “We have books in each of our little condo’s rooms. There is not a room for a separate library.”

Norwood buys books, borrows from the public library and reads on Kindle when traveling. “I have been accumulating books all my life, and we still have some books from our childhoods.”

Bibliophile Regula Spoti, a Swiss transplant to the Triad, was inspired by Bibliostyle: How We Live at Home with Books. She buys e-books monthly but estimates now owning 150 books despite “giving books away liberally — and I only want meaningful books in my library.”

Greensboro reader Nancy Jones belongs to several book clubs, now keeping a minimum of 300 books in her home. “I have four different areas with books collected — one whole wall book-cased in my family room with mostly books, a few art objects. And a lawyer’s bookcase at the end of my hall.”

Virginia Cummings, avid reader and fellow “bookie,” created a wall of bookcases in a living room filled with books she and her husband still pull off the shelf to reread. “I love to see my family and friends browsing and conversing about the books,” she writes. But there’s a caveat: “One son, who reads classics, tries to sneak them back to his house.”

The Tender Bar, based on J. R. Moehringer’s book, features a scene in which the writer’s uncle opens a closet stuffed with classics. These, the uncle says, must be read before he can consider himself educated.

Moehringer’s first bosses at a bookstore explain that every book on the shelf is a miracle; “it was no accident they opened like a door.” Whether that door is discovered within a grand library, like Vanderbilt’s, or a closet, like his uncle’s, it opens us too. OH