Out of the Blue

OUT OF THE BLUE

Out of the Blue

A former neighborhood show house shines again

By Cassie Bustamante

For years, Scott Bisbee had told his wife, Lindsay, about his dream of owning a grand, gray house. With the address in her GPS, Lindsay did a drive-by of a soon-to-be-listed Lake Brandt Estates home. “I got goosebumps,” she recalls. The muted gray-brick home sat far back on a large lot and, from her car window, it looked like the physical manifestation of Scott’s dream. The hidden-behind-overgrowth-gem version, that is.

Over a decade ago, the Bisbees became Greensboro residents when Scott, who has been with Honda for most of his career, took over management of the Crown Honda Greensboro franchise. Previously, they’d lived in California’s Bay Area in a town called Danville.

While their Golden State home featured a zero-lot line, their first Greensboro house, a new build in Gates at Brassfield, “sat on a pie shape with the house in the middle of it,” says Scott. “Coming from California to that house? That was a huge upgrade in property.”

But as the Bisbee children grew, the family’s needs changed, too. Plus, they wanted to be on the north side of the city because Scott, too, made a big career move.

“It’s kind of hilarious,” quips Lindsay.

“It’s awesome!” adds Scott.

Years ago at a Honda meetup, before their move to North Carolina, the Bisbees spotted a man with a Danville baseball cap on and struck up conversation, asking if he was from the same East Bay town. Turns out the gentleman, Steve Padgett, was the owner of Honda of Danville in Virginia. Not California. But a friendship was forged and they stayed in touch throughout the years. “And then one day the guy calls Scott,” says Lindsay, in hopes of selling his dealership.

In 2019, Scott firmly put down East Coast roots, purchasing Honda of Danville. “We’re lifers now,” he says happily of North Carolina.

Lindsay, too, began her own business in North Carolina. Before having kids, she worked as a chemist and microbiologist and took her knowledge into cooking for her family, cutting out unnecessary chemicals. Eventually, in 2015, she launched Kyookz, an “artfully pickled” company that offers four pickle varieties in more than 450 store. Their daughter, Taylor, now 24, is currently running the company. Lindsay says that, now, her home is her “new job.”

With their wishlist in mind, the Bisbees struggled to find the fixer-upper of their dreams — a spacious home on a large lot in an established neighborhood, something Lindsay could put her own design spin on. After searching for a couple years, they all but gave up.

“We actually did give up,” says Scott.

But, “out of the blue,” Lindsay says, their friend and Realtor Frances Giaimo called. “She said, ‘Guys, I think I found the one for you.’”

The home had once been “the show house of the neighborhood, according to neighbors,” says Lindsay. It was built in 1987 for Irish-born Ingrid Dougan Hayes McMillan, a former wife of millionaire and textile giant Chuck Hayes, longtime Guilford Mills CEO. According to Lindsay, Ingrid lived there until she succumbed to brain cancer in 2011 at the age of 53. Neighbors have regaled the Bisbees with fond recollections of the beautiful woman who often hosted get-togethers. “Her hair and her makeup and her dress were just perfect and she would be riding her little lawn mower,” says Lindsay. “She took a ton of pride in it.”

Like Lindsay, Ingrid also had an eye for design that was evident throughout.

But the large, contemporary brick home had been occupied by renters for a few years and, before that, had sat vacant. The result? The former jewel of the neighborhood had become a diamond in the rough, buried in overgrowth. Frances, who lives just down the street, caught wind that it would soon be hitting the market.

The sellers’ real-estate agent allowed Frances to take the Bisbees through the home before it hit the market. “It was very 1980s,” recalls Lindsay of that first walkthrough. Plus, the renters had left behind cigarette burns and worse.

As they reached the landing at the top of the stairs that day, Scott remembers looking at his wife and saying, “Do you have any idea how much work this is going to be?!”

But Frances encouraged them to take a look at one more thing — the basement.

“It’s a huge walkout basement that goes underneath this large deck,” says Lindsay, who saw that space and imagined what it could be: an indoor-outdoor space for entertaining with a patio kitchen and views into the peaceful wooded creek behind the house.

“I just felt like it was the one we had been talking about for so long,” says Lindsay. And, having renovated homes on their own in California, a large project did not scare them.

They put in an offer, which the sellers accepted. “It was kind of win-win for everyone,” says Lindsay, since the home never even had to be listed.

Immediately, they got to work and hired architect Stephen Jobe to help them make structural changes on the main floor. Where a small dining room once sat adjacent to a guest room, the couple moved walls, creating a downstairs primary suite.

“We weren’t going to use [the dining room] anyways because we’re not fancy,” says Lindsay, whose style leans California casual. But a main-floor primary would be ideal to allow the couple to avoid stairs as they get older.

“You typically wouldn’t put a primary at the front of the house either,” says Scott, “but because we sit so far back, it’s still dark and private.” In fact, the front yard slopes downward toward the home, allowing their bedroom, decorated in soothing grays, tans and whites, to remain tranquil. Over the bed, a canvas Lindsay created using alcohol ink features soft colors and touches of metallic gold.

The en suite bathroom is Lindsay’s “second-favorite” space in the entire home. From the heated porcelain-tiled floors to the wet-room shower, “it’s just very cozy.” The soft, neutral palette of taupes and whites lends to a spa-like serenity.

In fact, the colors throughout the home remain cool and calming. In the main living area, white sofas are anchored by a beige-and-gray area rug. An ash-colored, large, square coffee table complements the light wood floors, which have been refinished throughout. But the fireplace wall provides contrast in Sherwin Williams Charcoal Blue, which helps to mask the wall-mounted television.

“It’s been really fun to play with some different colors,” says Lindsay. “I wanted it to be neutral and light, but then I had to do a pop of dark to offset it.” Textiles, such as throw pillows, play off the fireplace wall.

Sitting in this room, one could almost imagine the Pacific Ocean lapping at the shore just beyond the windows. “I think it would be very hard to shake the West Coast out of me,” quips Lindsay.

From his chair in the living room, Scott calls for the family dog, Astro, and asks him to take a selfie. Astro, you see, is not your standard pooch. He’s a Honda-made robot. A long camera extends from his head and he snaps a photo.

“He’s like our little security dog,” says Lindsay. When no one is home, Astro roams the interior with his camera. Of course, the couple’s sons — Hunter, a freshman at Providence College in Rhode Island, and Jake, a junior at Greensboro Day School — have discovered a workaround when they’re at home and their parents are not: “One time, they turned him on his side so he couldn’t roam around and find them and video them.” (Taylor lives in her own apartment locally.)

Astro rolls back over to his resting spot by the back door in the kitchen. Just beyond that door lies a large deck, a deck that Scott almost fell through. The renters had kept a fire pit on the wooden deck, which had then burned and rotted in spots. “It was probably a couple weeks away from collapsing,” says Scott. “And I am standing on top of it like, is it supposed to bounce like that?”

The couple had the deck reinforced but Scott says “Wendy” resurfaced the deck. Wendy?

“Wendy the builder from Bob the Builder,” Lindsay replies. Turns out Scott’s nicknamed his handy wife.

DIY skills seems to run in the family. Lindsay gestures to a homemade game table, complete with dice, sitting on the deck. “Oh gosh, this is part of our frat house now that our son’s home,” she quips about the makeshift piece her son crafted with his friends after a trip to Home Depot.

Of course, Scott sometimes gets in on the action, too, staying up late to be one of the boys. “Lindsay made me go to bed two weeks ago,” he says with a laugh.

“You do have to get up in the morning!” she notes.

When the boys aren’t out there playing, Lindsay notes that she and Scott enjoy closing down their nights together on the deck with a glass of wine. In fact, when the kitchen was being remodeled, the couple added a large glass wine cellar, which sits in the corner.

When the Bisbees lived in California, Napa was a short drive away. While there, a friend introduced them to Scarecrow, a hard-to-acquire California cabernet. To even have a chance, you need to add your name to a list and hope that one day you get a call. Scott added his name and years later received the call.

“This one is in a league of its own,” Lindsay says of the wine, proudly displayed in the cellar, which stores up to 480 bottles.

“It’s like a trophy,” muses Scott of the Scarecrow bottles.

That makes the cellar itself a bit of a trophy case, tucked into the corner of their favorite renovated space — the kitchen. Lindsay had been dreaming for so long about renovating a kitchen before she even saw this house that she already knew what countertops and appliances she wanted. The Bisbees hired SR Design Group to bring their vision to life.

“It’s everything I ever wanted,” says Lindsay. Everything being double islands, two double dishwashers, white cabinetry, quartz countertops with taupe veining, a walk-in pantry.

The double islands have created conversation areas. “Everybody always congregates in the kitchen,” says Scott, recalling a party they hosted where only a couple people sat on the cushy living room sofas, but two groups were gathered around the islands talking.

And for Lindsay, who loves to cook, bake and entertain — just as Ingrid once did in this home — the storage space between all of the cabinetry and pantry closet makes a huge difference. “When we were in California we literally had our large serving dishes under beds,” she recalls.

While the kitchen was a complete transformation, Lindsay notes that they tried to keep some of the original character, such as the fireplace, which they had retiled. “It’s super random to have a fireplace in the kitchen, but I thought it was so charming,” she says. “It makes it feel old-school cozy.”

The look of that fireplace is mimicked in the fireplace of the upstairs primary, where Hunter stays during his summer break. Gesturing to the wall the headboard sits on, Lindsay notes that she’s recently wallpapered it with a large-scale palm leaf print in charcoal and tan. In fact, she says, she’s wallpapered a few more walls and nooks throughout the home. “It’s so in right now so I started and then I couldn’t stop,” she says with a laugh. “I think I should slow down.”

But her creative mind is always at work. The bedside dressers are from Ikea, but she’s painted them black and added modern gold hardware. The walls are adorned with decorative molding she installed and painted herself.

“Wendy the builder” has been at it in the spare bedroom as well, which features wall molding and a cherry ’80s dresser she’d contemplated donating. Instead, with paint and elbow grease, she gave it a fresh look.

“Where else are you going to find a green [dresser]?” Scott asks.

In Jake’s bedroom, a similar charcoal palette echoes the upstairs primary. Again, Lindsay’s added molding. A large painted canvas hangs over the bed — a Lindsay Bisbee original, like much of the artwork adorning the home’s walls.

On an adjacent wall, Jake — whom Lindsay still refers to as “my little guy,” despite the fact that he’s outgrown her — has created a grid gallery of square pieces. Photos? Nope, album covers he’s had printed.

Turns out he and his brother are both into records. Down the hallway in a little — wallpapered, of course — nook sits a vintage-style Victrola record player where Hunter plays old vinyls.

The teen boys also share their own upstairs laundry room. Lindsay peeks in and sees clothing strewn on the floor. She shuts the door. “They are working on some stuff in there — hopefully!”

But at the back corner of the house sits the boys’ well-used shared space — a lounge designed just for them.

“You can smell boys up here,” quips Scott. The back wall has been papered with a simple dash design in black and white and the furnishings are simple and comfortable. At the boys’ request, larger chairs were replaced with cost-effective beanbag chairs, perfect for video gaming.

Lacrosse helmets earned from various showcases line the walls leading to their retreat. Hunter, Scott says, earned his varsity letter in the sport during his freshman year in college. “Proud dad moment!”

Jake, it seems, is also making his mark on the sport, earning helmets and jerseys to add to the collection. In fact, for the first time in the school’s history, Greensboro Day School, the team he plays for, won the state championship this past May.

As it turns out, part of the reason the Bisbees initiated their move was that as their athletic sons grew older, their power and speed strengthened along with them. Lacrosse balls sometimes bounced off neighbor’s houses at their former Duck Club abode.

But now, in their Lake Brandt Estates home, they have the space and privacy they craved. No more errant balls make their way into neighbor’s yards or windows.

And thanks to Lindsay’s design eye and DIY skills, what was once a dream house is just that again. “The neighbors are appreciative, too,” says Lindsay. “They talk about [Ingrid] and how much she loved this house, so they’re very happy there are owners that care about it now.”

“I don’t want to say that she’s still here,” says Lindsay, “but I feel her presence is still in the bones of the house.”

And wouldn’t Ingrid herself be pleased to know that her legacy is being carried on in the home she poured so much love into?

The Bisbees continue to put their hearts into making the Lake Brandt Estates home shine again. Most recently, the couple hired Vasquez Painting Company to transform the exterior with Sherwin Williams Shoji White. So what happened to that gray-house dream of Scott’s?

“Now my favorite house is white!” he jokes.

Use Your Voice

USE YOUR VOICE

Use Your Voice

A new production celebrates the suffragettes

By Cynthia Adams

When director, musician and playwright Sherri Raeford was invited to dramatize the struggles “of courageous and resolute women of North Carolina to obtain equal rights” she was struck by the diversity of the those who pioneered the right to vote for women in the state. Many of the stories were Asian, Black, Jewish, Native American, Immigrant Irish and white Americans, she learned.

American Association of University Women North Carolina (AAUW NC) president Cheryl Wheaton envisioned a 2020 performance to be given in Raleigh at the Governor’s Mansion for a special centennial. Raeford, who thrives on group projects, was elated that the diverse group of women she pulled into the project were loving it, too — so much that they agreed to even be cast members. The writers included Jalila A. Bowie, Sheryl Davis, Patsy Hawkins, Ruan Walker, Lennie Singer, Chappell Upper and, of course, Raeford.

“The original idea was to envision women at the Governor’s Mansion on the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage,” she says. Raeford is owner of Shared Radiance Performing Arts Company, which she founded after years directing the North Carolina Shakespeare Festival.

Underwritten by a grant award from the AAUW and later supplemented by High Point nonprofit Women in Motion, or WIM, the original work, Sisters of Mine; Hear the Voices, will finally come to the stage at two Triad locations on August 24 and 29 after COVID disrupted that original production.

Raeford has spent years researching and dramatizing events surrounding the passage of the 19th amendment. Ratified on August 26, 1920, the centennial observation — four years after the fact — will serve to mark Women’s Equality Day.

She held developmental meetings in her Pleasant Garden studio.

“A lot of the women who contributed [to suffrage] were women of color, and I didn’t want to write other people’s stories.”

That was then.

“When [the project] began,” she recalls, it was exhilarating. “There was a lot of momentum.” Raeford sighs. “Then COVID hit.”

With the pandemic raging, the group attempted collaborating on Zoom rather than in person. That proved difficult, Raeford admits. The production lost steam as the pandemic ground on. Eventually, the project stalled.

Raeford grieved a bit, then “let it lie for a few years.” She regrouped as best she could during the pandemic, staging open air company productions in the interim. Best known for bringing classical and original works to students and into the general community, Raeford’s company, Shared Radiance, is a member of the North Carolina Theatre Conference and the Shakespeare Theatre Association.

Shared Radiance productions frequently use outdoor locations, including parks and public space, where the audience follows the actors from scene to scene. So, using the outdoors as the stage was nothing new to her.

Open air performance, as it turned out, was a godsend during the pandemic.

Shared Radiance board member Martha Yarborough had learned about the developing production during those COVID-era Zoom meetings. Almost immediately, she grasped that the theme of women’s equality was a fit with another organization, WIM, a leadership initiative founded in 2015. She felt WIM would instantly see the production was “about finding a voice.”

Yet Sisters of Mine might never have found its voice, Raeford stresses, if not for renewed interest from AAUW NC. “The AAUW Greensboro branch recommissioned the production to highlight today’s equity issues for women,” the organization explained recently in a release.

With AAUW’s renewed interest, Raeford was further buoyed when WIM sought a second performance in High Point for their organization.

As a result, Sisters of Mine could stage two Triad performances bookending Women’s Equality Day on August 26.

Linking two of her passions, theater and leadership, Yarborough is delighted that Sisters of Mine reemerged following a dramatic five-year disruption.

“Since 2000,” says Raeford, “Martha has been my muse.” A former educator, Yarborough played a supportive role for a former student, this time by calling Sisters of Mine to the attention of WIM’s director, Pam Baldwin, and fellow board members.

WIM decided to use Sisters of Mine to announce 2024 grant winners in conjunction with the performance and “use it as a special platform for an annual event as well,” says Baldwin. She explains that the organization serves to elevate and support women in achieving professional goals, which seemed a natural fit for the premise of the play.

“The play speaks to the importance of using your voice and being empowered. One way you can exercise your voice is by voting . . . which these women [suffragettes] fought for.” And there is a dramatic tie-in with WIM.

“Half of our organization’s member dues go into a giving pool,” she says, in discussing WIM’s grant process. Each year the membership votes on allocation of monies raised.

“Obviously, because the women in our organization get to vote on all grants,” the production’s theme of voting rights suited their purpose.

“So, tying all that in and making the celebration of the grant [awards] just elevates it. We’re coming together, talking about our mission, who we are and what we do, and also have a program that they can enjoy as well. It came about organically.”

She adds, “We want them to come, to learn about us, and see where their money would go as a member.” She liked the idea of free admission, following the lead of the AAUW’s premiere in Greensboro.

“Rather than charging as a fundraiser, we want to flip the script a little [by offering free admission].”

Their hope? That mothers and daughters, women from all walks of life, will attend the play.

Yarborough agrees with Baldwin, envisioning that a performance about the rights of women “will illustrate Women in Motion’s collaboration with other groups.”

Today, Sisters of Mine is not the traditional play it began as. While the original premise of the suffragette-themed work has morphed into a performance piece with original music, it still cleaves closely to the original concept — reflecting “women of diverse histories” seeking equality, according to playwright Raeford.

She is pleased that the handpicked collaborators authentically reflect the varied background of the original suffragettes, calling it a “performance collage.”

Raeford, who is an avid musician and composer, wrote an original song for the play based on the poem “Sisters of Mine” by North Carolina poet Barbara Henderson, who “had written poems about the suffragette movement.” After composing the music, Raeford asked musician Robin Gentile to help arrange the song, and to perform it on flute and guitar.

With five years elapsed, the core group changed. Their post-pandemic life circumstances altered. One of the original writers moved away.

Again, Raeford regrouped, assembling a “multi-generational cast,” some in their 20s and others in their 70s. The Sisters of Mine cast includes original writers and cast as well as new cast members Jamila Curry, Robin Gentile, Cynthia Reichelson and Sarah Wilson. Understudies Camille Christina, Candace Hescock, Grace Kanoy and Kelly Kerr will be waiting in the wings. Sarah Wilson is the stage manager.

“The beauty of the generations is also the beauty of women . . . all taking care of each other,” explains Raeford.

“This is what this is all about,” adds Yarborough, connecting the struggle for parity in the workplace and as individuals. “Fighting for our rights. Using your voice.

The Wyndham Way

THE WYNDHAM WAY

The Wyndham Way

After 85 years, Greensboro’s beloved PGA event is still making history

By Jim Dodson

One morning 25 years ago, while working with Arnold Palmer on his memoir, A Golfer’s Life, I asked the King of Golf if there was one tournament in his illustrious career that he regretted never winning.

I was sure he was going to say the PGA Championship, the only missing major.

Arnold was sitting at his workshop desk, putting a new leather grip on his driver. But he paused and gave me what I’d come to think of as “The Look,” a cross between a constipated eagle and a very disapproving school master.

“Really, Shakespeare?” he growled. “You really have to ask? You of all people should know the answer. After all, you grew up there!”

He meant, of course, my hometown Greater Greensboro Open, which I attended almost every year of my life growing up in the Gate City, including the year after I went off to college, when Arnold had his best chance ever to win the tournament. He led the final round until a triple bogey on the par-three 70th hole allowed lanky George Archer to win at the wire.

“I never quite got over that,” he admitted with characteristic candor. “I had so many friends in the gallery from Greensboro and Winston-Salem, plus my connections with Wake Forest [University]. It still chews at me. That tournament was so much fun and meant a great deal to me. I just never got the job done.”

The King may have regretted failing to win the GGO, as it was affectionately called, in front of the homefolk faithful, but the tournament known today as the Wyndham Championship has never forgotten Arnold Palmer.

Yes, that tournament: in its 85th year, set to begin Thursday, Aug. 8, and continuing until Sunday, Aug. 11. All eyes, as usual, will be on the Wyndham because it determines which 70 PGA Tour golfers will advance into the FedExCup Playoffs.

Several years ago, his grandson Sam Saunders watched as Wyndham officials installed a plaque dedicated to Palmer on the Wall of Champions behind the ninth green at Sedgefield Country Club. The plaque reads: “Widely considered the most important figure in golf and one of the most influential players in Wyndham Championship history, Arnold Palmer had five top-five finishes in 13 appearances at Sedgefield.”

From its modest beginning as the seventh oldest golf event on the PGA Tour, won by Sam Snead in 1938, the Wyndham’s legacy of winning champions who made their mark on American golf can be matched by few PGA events. The list includes legends such as Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Sam Snead (who won the GGO a record eight times), Gary Player, Billy Casper, Larry Nelson, Raymond Floyd and a dashing young Spaniard named Seve Ballesteros, who won his first tournament at Greensboro in 1978 en route to superstardom.

The last nine decades have seen at least three different sponsor name changes before Wyndham Hotels & Resorts became the tournament’s stalwart title sponsor in 2007. All that time, the Triad’s beloved golf tournament — North Carolina’s first professional event — retained its unique personality and important place in the world of professional golf.

“It’s essentially unique for a variety of reasons,” says Executive Tournament Director Mark Brazil, who started with the tournament in 2003. “You can begin, of course, with its almost incomparable history, which rivals the majors in terms of legends who won here. But its evolution under Wyndham has made the tournament even more special in several ways.”

One notable way, he points out, is the strong emphasis the Wyndham places on being a premier fan-friendly event, a five-time winner of the PGA’s top hospitality award for fan accessibility and friendliness.

“Most tournaments actually focus most of their attention on the players, going out of their way to provide luxury accommodations and services, anything they can to make the players feel welcome. We do the same thing, of course, but the key to our hospitality focus has always been the fan experience, the paying customer who might come out for a day or the entire week in the heat of summer to watch the greatest players in golf.”

Brazil points out that at a time when fan bleachers are disappearing from the grounds of some tournament venues, the Wyndham features numerous bleachers, enhanced spectator viewing areas and much-lauded cooling areas all over the Sedgefield property. The Wyndham’s popular Margaritaville tent, Truist fan pavilion, Sunbrella Sun Deck and Wyndham Rewards areas have become hallmarks of the its laid-back, hometown family feel.

That’s just the Wyndham way.

Another facet of the tournament’s appeal is the opportunity to watch younger players on the rise who may someday become the next Seve Ballesteros. The likes of British Open Champ Sandy Lyle, a young Davis Love III and Webb Simpson have won the Wyndham on their way to stardom. In more recent times, even older players such as Sergio Garcia and Tiger Woods joined the field, hoping to claim some Wyndham magic and the tournament’s Sam Snead trophy. Garcia made himself relevant on the PGA circuit by winning the tournament in 2013. A recovering Tiger Woods gave fans a thrill and left a good impression on fans by comparing Sedgefield and its history-rich Donald Ross golf course to baseball’s historic Wrigley Field.

At a time when professional golf is in flux, perhaps the Wyndham’s biggest recurring storyline is its coveted position as the last regular season event where players can make a run at finishing in the Tour’s Top 70 rankings, thus qualifying for the FedExCup Playoffs that begin the following week in Memphis. The tournament also helps determine the top 50 players who qualify for the next season’s “signature events” that sport $20 million purses after reaching the second FedExCup Playoffs event. Sweetening the attraction, there’s also the $40 million Comcast Business Tour Top 10, rewarding the top-10 finishers in the PGA Tour regular season.

Finally, players who find themselves potential “captain’s picks” for the President’s Cup and Ryder Cup, have a final opportunity to make a big impression. In 2023, both Ryder Cup captains Zach Johnson and Luke Donald played in the Wyndham Championship for this very reason.

“This explains why we generally leave the players alone,” Brazil notes. “They have important business on their minds when they get here. There is so much riding on their performances. In many cases, the Wyndham becomes the last opportunity of the year to advance their careers. As we like to say,” he adds, “the finale is really the beginning.”

Aside from its strong community outreach programs, including longtime support of the First Tee—Central Carolina, each year seems to bring a nice, new wrinkle in terms of the tournament’s service to the Triad.

Earlier this year, partnering with First Tee, the Wyndham put out a nationwide call for artists to create an outdoor wall mural honoring the civil rights pioneers the “Gillespie Six” at the Gillespie Golf Course, to be commissioned by Wyndham Rewards and overseen by the City of Greensboro.

With Gillespie’s continued revival in mind, a panel of key community figures and organizations selected a trio of finalists from more than 50 artists across the nation to design an outdoor memorial that will honor the Greensboro Six at Gillespie Golf Course. The mural is commissioned by the Wyndham Rewards Program.

In mid-June, Vincent Ballentine was announced as the artist who will paint the Greensboro Six mural on the First Tee—Central Carolina building at Gillespie Golf Course. An artist’s rendering of the mural was unveiled at the time, honoring the course’s history with a depiction of the six pioneers as well as a vibrant nod to the diverse future of golf.

Ballentine hails from Brooklyn, New York, and is a multidisciplined visual artist known for large-scale outdoor murals commissioned by the likes of MTV, the NCAA and BET. At the June announcement, First Tee—Central Carolina CEO Ryan Wilson praised Ballentine’s mural plan, saying it “captures our vision of bringing the community together through the power of golf and will serve as an everyday reminder of our storied past and — because of that — our beautiful future.”

Ballentine also addressed the crowd: “The Gillespie mural honors courageous men who overcame deep-rooted racial challenges to inspire incredible change.” His hope? That his creation will generate thoughtful conversations about the importance of inclusivity while paying homage to the Greensboro Six.

The mural will be publicly unveiled during the Wyndham Championship Jr. Golf Clinic on August 5, 2024, kicking off the Wyndham Championship.

The latest example of the Wyndham Way. OH

Tumbleweed

TUMBLEWEED

Tumbleweed

Fiction by Shelia Moses • Illustration by Raman Bhardwaj

My man is like a tumbleweed. He just rolls around and catches everything that crosses his path — every woman that is. I am telling you he’s just like a tumbleweed. That is the reason I did not want to come to this one-horse town to live. But Hogwood, North Carolina, is my Tumbleweed’s home, and he wanted to come back to be near his dying daddy. That was four years ago. His daddy, Mr. Pop, is still alive. So why are we still here?

I knew Tumbleweed would start rolling with the gals that used to love him as soon as the train stopped in Weldon to let us off in 1952. We was only here one day before we ran into one of his old gals, Missy, in the grocery store. That was the beginning of Tumbleweed going back to his old ways. First he told me that Missy was his cousin. Then I looked at that boy of hers, Boone, and I knew Tumbleweed was lying. I knew he was the daddy. Look more like Tumbleweed than Tumbleweed look like himself.

“Come on Sweet Ida,” he said to me.

“Come on nothing, Tumbleweed. You lied to me again. You know good and well Missy ain’t your cousin. You know that boy is your boy.”

“Na’ll Ida, Boonie ain’t no boy of mine. I only got six boys and two girls. You know that.” He say that mess like he proud that he left a baby in every town between Wildwood, New Jersey, and Hogwood. He ain’t never had no wife, so what he bragging for?

Missy ain’t saying a word. She just smiling and turning from side to side like she can’t stand still around my Tumbleweed. That boy Boonie ain’t got good sense. He don’t even know what we talking about. Guess we better leave before he eat up all the candy in the grocery store that Missy ain’t even offered to pay for. He definitely Tumbleweed’s boy because he always want something for nothing.

Can’t be too crazy, now can he?

“Oh stop looking for reasons not to love me gal.” Then Tumbleweed pulled me in his arms in the store that was filled with people. The store always filled with people from Rich Square, Jackson, and Hogwood on a Friday evening. It’s payday, even for the field hands. The womenfolks was looking when Tumbleweed pulled me closer. I forgot all about that boy that looked just like my man. I remembered all the reasons I love myself some Tumbleweed.

I love him for the same reason all these North Carolina womenfolks love him.

He a man! A real man! My man!

He ain’t all fine or nothing. He just a man that you gots to have.

Come that Monday morning we was back working in the ’bacco field. I was hanging ’bacco in the hot barn loft while Tumbleweed drove the truck for Mr. Willie who own all this land and ’bacco. Right now he ain’t driving. Tumbleweed just sitting and waiting to take us home. I think Mr. Willie had extra folks in the field that day. Extra women to prime this ’bacco. Extra women to look at my Tumbleweed.

They can’t fool me. That old Bessie was there shaking her big behind all over the place. She the only woman I know that wear tight skirts in the ’bacco barn. I can’t believe I left my job waiting tables at that rich country club in Wildwood to come here to prime ’bacco. Tumbleweed claimed it is a good way to make a living.

Look at him sitting over there looking at me up here in the loft and all the other women that love him out in the field.

“You want some water?” Bessie yelled to my Tumbleweed when it was time for us to knock off for lunch.

He did not answer her.

He better not!

“Anything Tumbleweed want, I can get for him,” I said, climbing down the hot barn loft for lunch.

“Fine,” Bessie said as she laughed like she knew something that I did not know. “I can get Tumbleweed some water later tonight,” she whispered and walked over to the tree to eat her pork and beans and crackers.

“Say it again,” I said as I ran up behind her. Bessie turned around in slow motion. She must have eyes in the back of her head.

I did not get far when them sisters of hers all jumped up from the ground at the same time.

“Where you going city girl?” her oldest sister Pennie Ann asked as she rolled up the sleeves on her shirt while kicking her can of beans out of the way.

I will fight anybody, anywhere for my Tumbleweed, I thought to myself.

I tried to roll up my sleeves too.

That is all I remember. The next thing I know I am lying in the back of Tumbleweed’s truck and he’s looking down at me.

“How many fights you going to have girl?” he said like he was almost sad.

“How many women you gonna love Tumbleweed?” I said as I reached for my head that was really hurting now. The knot on it felt mighty big.

Tumbleweed leaned over me and kissed me real hard with his big black lips.

All the womenfolks looked at us. They wished they was me.

An Afternoon, No Wind

AN AFTERNOON, NO WIND

An Afternoon, No Wind

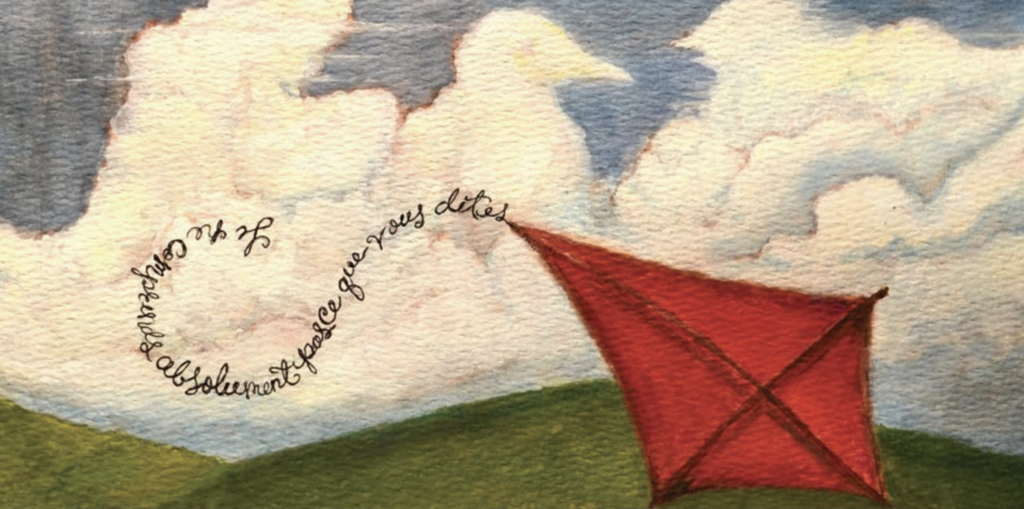

Fiction by David Rowell • Illustration by Keith Borshak

A striking, big-boned woman runs back and forth trying to fly a kite. She is surprisingly eager, considering there is no wind today. There is not enough of a breeze to sail the gum wrapper off the bench I’m sitting on. She darts tirelessly across the park as the kite drags behind her like a little dog. Every so often the kite lifts off the ground, though no higher than her head, and that’s only because she is a fast runner. This goes on for an hour.

I’m supposed to be helping my ex-girlfriend move her tanning bed into the spare room. But when the woman with the kite throws her arms up in an almost vaudevillian show of disgust, I get up, stiff from the wooden slats, and walk over to her. She isn’t aware of me until I am close enough to touch her.

“Tough day for kites,” I say.

We look at each other, and for a few seconds neither of us seems sure what to do. I back up a step or two. I am suddenly confused and can’t remember if I have spoken yet or just thought about what I might say. Tough day for kites?

“Je ne comprends absolument pas ce que vous dites.” I know it’s French, but I don’t speak a word of it. Watching her earlier, it didn’t occur to me that she wasn’t American, but up close I can see the faint olive glow of her skin, the slightly pouty curl of her lips. I consider turning around, leaving her alone, but there is something helpless about her and her shiny but now damaged triangular kite. I point to the kite, then to the sky. I blow a deep breath and shake my head no.

“No wind,” I say slowly, so slowly that I am keenly aware of how my lips feel when they move. “There is no wind.”

We stand another moment in silence, as the strangled cry of taxi horns and someone’s high-pitched laughter and the rusty churn of a nearby bicycle chain play off each other like jazz musicians. Behind the woman a mass of clouds forms a penguin, then a penguin on skates. She says something — something abrupt, like an order — and points to the kite. She points at me, then to the kite again. I reach down to pick it up.

“Oui,” she says.

I raise the kite slowly over my head, arching my brow to say, Is this OK? Is this what you want? She doesn’t indicate one way or another. Out of the corner of my eye I notice that two older women who are dressed for the tundra have stopped to watch.

She backs up and lets some string out, all the while staring into my eyes so intensely that I am afraid to look away. She nods her head once, the way mob bosses in movies indicate their willingness to listen first, before killing. Then she turns and starts sprinting, divots of grass spraying from her heels. The kite jerks out of my hand and immediately sinks, not quite hitting the ground because, as I say, she’s fast. Her ponytail thrashes behind her like a fish pulled into a boat.

She goes probably thirty yards before she looks up at the speckled sky, where she expects the kite to be. Her sturdy legs slow to a gallop, which causes the kite to touch down with feathery impact. The sad sight provokes her to grunt from the diaphragm and kick at the ground with such force that she nearly falls over. Her large frame heaves in and out. She yells something at either me or the kite (the literal translation might be, “What a piece of crap are you!”). I point up at the sky again and shake my head.

When she finishes winding up the string, she puts the kite back in my hands. I notice two small but distinct moles above her right eye. She catches me looking and balls up her face like a fist. She gives me an earful about something, to which I shrug and smile, though not with my teeth.

All afternoon we do this. And every time we try, I can tell that she expects it to go differently. Sometimes I shake my head in mock disbelief. Other times I grab a handful of grass and launch it into the air, as if that might tell us something. Once I try to hand the kite back to her and reach for the string, thinking she might appreciate the break. But she shakes her head in a frenzy, the way monkeys do in TV commercials, and holds the string behind her back. She tries running harder and for longer. If I hold the kite up with my arms even slightly bent, she refuses to start running. When yet another attempt fails, she violently reels the kite in. As we get ready again, she sucks some air into her locomotive lungs, then gives me the signal to release.

By now the sun has melted to the bottom of the sky, leaving behind a fiery red glaze. People walk by with their necks turned at awkward angles, their mouths agape with wonder. My French companion is still for the first time all day. We stand there awhile, just a few feet apart, but it’s hard to believe we’ve spent the entire afternoon together. If I ran over the hill and brought back two sno-cones, I wonder if she would even recognize me.

The man at the pretzel cart is folding down his umbrella. I imagine a big wind suddenly sweeping through the park and lifting the umbrella up over the trees, the man kicking wildly in the air as he tries to hang on. When I look over again at my partner in aeronautics, it takes me a moment to realize that she is tearing up the kite. She grips it in her muscular arms and splits it down the middle. She yanks out the sticks of the frame, fumbling with them until she snaps them over her knee. Then, with lips moving but making no sound, she grabs the tail with both hands and tries to twist it off, but she loses patience with it and is content to leave it a thin, raggedy string. Her hands are a frenzied blur of methodical destruction, though her face has an even, almost serene expression. When she is finally satisfied, she bundles up the remains and hands them to me. Instinctively I reach out to cradle the wreckage.

She lumbers toward the wrought iron entrance of the park, past the statue of George Washington on his horse, past a little boy trying to step on his balloon, which keeps darting out from under his foot. She steps directly in front of a stretch limousine so that it has to slam on brakes; still, the driver senses enough not to honk. She mows through the streets with an elephantine grace and does not fade from view until well after the darkness settles in.

I COULD GO OVER THIS AGAIN, say at what point this, then that, but it would more or less come out the same. And yet there is something that I can’t account for, even now: In my arms the kite felt like a bouquet of flowers.

The Music Lover

THE MUSIC LOVER

The Music Lover

Fiction by Katherine Min

Illustration by Jesse White

Gordon Spires lived across the courtyard from Leonard Hillman, concert master of the M Symphony, and his lover, Kyoung Wha Jun, the second violinist. Leonard and Kyoung Wha often practiced together outside in the courtyard, under the brim of a large oak tree. The neighbors would hear them playing Debussy or Brahms and sometimes something contemporary that they wouldn’t recognize.

Gordon liked to listen to them. He was in love with Kyoung Wha, who was slender and lovely, and he believed that she secretly returned his affection but could only reveal it through her music. So when she played Mozart, it was because he was Gordon’s favorite, and when she played Bach, it meant that she was biding her time, and when she played Tchaikovsky, it was surely a sign that she was ready to run off. For it was well known that Leonard beat Kyoung Wha when he was drunk, that he cheated on her with the first violist, and that he had not quit smoking like he told Kyoung Wha he would, but snuck cigarettes after matinee performances. At least these things were well known to Gordon, who was sickly and often home during the day.

One Sunday afternoon in late autumn, Kyoung Wha and Leonard played Beethoven. From his bedroom window, Gordon could see them, Kyoung Wha in a pleated blue skirt with prim white blouse, her long bangs swinging in her face as she swept her bow across the strings of her violin; Leonard, his narrow face impassive, eyes closed, chin tilted up at an unpleasant angle. Gordon could distinguish the rich, vibrant tones of Kyoung Wha’s playing from the darker, ruminative vibrations of Leonard’s, and he attributed the mistakes — rushed tempo, inconsistent meter, mawkish drawing out of notes — to Leonard, who was, in Gordon’s opinion, the inferior of the two musicians.

Taking careful aim, Gordon threw a Monopoly piece — a silver top hat — at the rounded, balding place at the back of Leonard’s head. Leonard did not stop. Gordon threw the wheelbarrow, the thimble, and the Scottish terrier. He used more force.

“What the — ?”

Beethoven came to a halt. Gordon peeked to see Leonard rubbing his bald patch, looking up at the oak tree, then down to the ground. Leonard shrugged at Kyoung Wha, who shrugged back. They resumed playing.

The next day, Gordon lobbed a satsuma, just grazing Leonard’s left temple. Leonard leapt from his chair. Kyoung Wha seemed to look straight at Gordon then, smiling sadly. Even crouched below his bedroom window, he could feel her smile penetrate his heart like the most tender of arrows.

A few days passed before they played outside again, Leonard setting up in what had formerly been Kyoung Wha’s spot, farthest from Gordon’s window, Kyoung Wha moving farther from Leonard, into a sunny patch that did not get much shade. Her face in sunlight looked faded to Gordon, wan, and when she played — Mendelssohn this time — he heard the silent suffering as separate notes from the ones that overlapped with Leonard’s, inhabiting the spaces between. She was even more beautiful in her despair, black hair against pale complexion, in an autumnal ensemble of mauves and rusts.

Gordon heaved a bottle of multivitamins, but it overshot its mark, landing, with a muffled plop, in a giant hosta.

It rained for several days after that, the afternoons overhung with mist. Gordon saw Kyoung Wha come into the courtyard in a yellow rain slicker. He thought her green rain boots splendid, as were the orange bill and bubble eyes on her hood, which were meant to make her look like a duck.

On the first clear day, Leonard appeared without Kyoung Wha. He began to play Mahler, his feet planted like andirons before a hearth. Gordon disliked the implication that music could simply go on without her. He wondered where she was, what Leonard had done to her. The lights were off in their apartment. He could see the white fringe of an afghan against the window, resting on the back of a blood red sofa.

Gordon palmed a large rock shaped like a dinosaur egg, with a rough, pock-marked surface. He raised the window and hurled it. The rock rainbowed up and out, hitting Leonard squarely on top of the head and bouncing off. The strings of the violin made a distressed, bleating sound as Leonard slumped sideways out of his chair, then fell face first against the brick walkway.

Time passed. The lights went on. Gordon saw Kyoung Wha come out, heard her call Leonard’s name. Approaching his body, she kneeled, bent to retrieve his violin by its broken neck, got up, and stumbled back inside. The lights went out.

Gordon listened, but all he heard was the sound of distant traffic.

Softly, he closed the window.

Where She Sits

WHERE SHE SITS

Where She Sits

Fiction by Randall Kenan

Illustration by Gary Palmer

They were in the little dining room off the kitchen when he finally told her. He paced about, motioning with his hands.

She just sat there, staring down. Feeling nothing. Maybe. Or just plain tired.

“I can’t do it anymore, Sandra,” he said.

Sandra said nothing. Slowly, she moved her hand over the oilcloth, steadying herself.

“I don’t care what your family says about me,” he said. “I don’t care. I can’t . . . I’m not . . . I’ve got to . . .”

She might have asked Dean about the children. But the idea that he would come up with some sleazy nonsense only made her feel a wave of nausea. Sandra put her head down.

Dean stopped behind her. She could feel the tension in the air; without seeing him, she knew he was clenching and unclenching and clenching his fists. He did that when he was angry. “Did you hear me? I’m leaving.”

Sandra raised her head. “Then go.”

He stood there for the amount of time it takes a frying egg to turn white and walked from the room.

Sandra reached out and caressed the table, and remembered. Not so much remembered as allowed a flood of images, past scents, past sights, to overtake her, fill the void she was now harboring. Each image evoked something like a feeling. So much took place in this room, upon this very surface. Not merely the food served, or the homework fretted over, or the cards played, or the beer spilled, or the puzzles arranged. Moments occurred right here. And now, in this instance of illusions shattered, of dreams wrecked and a heart frozen, these moments seemed to simmer before her, behind her eyes, and she could only hold on to them, to find some strength.

She had inherited this very table from her great-grandmother. Made of pine, by whom she did not know, it had been oiled, dented, dusted, polished, chipped, varnished, battered, peed upon, burned, broken, mended, hammered, nailed, or some such for decades. If it could feel, she knew she’d feel the way it felt now . . .

“Sandra? Damn it! . . . Where is my . . .”

The first true memory of her grandmother had been watching her across this expanse, on the other end, smiling and slicing with pride a piping hot blueberry pie. No, child, wait for it to cool. And so many mornings, days, nights, her mother at that same end: What you doing out so late? Sandra! An A in math! Now that’s good. Girl, don’t you ever raise your voice at me. I’ll knock the taste out your mouth! You heard about Uncle William, didn’t you? . . .

“Sandra, can’t find my . . .”

As if he actually expected her to come in there and help him to pack, to leave; as if any of this fault rested on her shoulders; as if she was expected to go along to get along; as if she would be unreasonable to go into the kitchen, get a butcher’s knife, and chop him into seventeen billion little pieces.

She ran her hand out against it again, against its smooth flatness, as if to absorb some of its stolid solidity.

Here, she served him his first taste of her cooking: catfish, greens, mashed potatoes, corn bread; here, she told her mother she was to wed the man who made her legs feel like overcooked spaghetti and her heart feel like butter. Here, where she tended him, listened to his tales of boring sales meetings and petty office feuds, and where he entertained his buddies (when not in front of the TV); here, where she fed and consoled and interrogated first one, then two daughters; here, where she slowly watched the shoals of her marriage erode, grain by grain.

Oh, if it could talk . . .

“Sandra.” He stood in the door. She didn’t want to look up at him. She had nothing to say.

“Good-bye.”

She did not look up, as he turned, wordless, and walked down the hall. As the door clicked behind him, she held fast. He may go, but some things would remain. A part, a piece, a fixture, a witness. Even now. OH

The Playhouse

THE PLAYHOUSE

The Playhouse

Fiction by Max Steele

Illustration by Mariano Santillan

The professor was standing now before the doors of the American Embassy. He was early for an appointment with an old frat brother, a legal attaché who would help him procure a fast Mexican divorce. There was no urgency really in getting a divorce. It was simply that he could not concentrate on a permanent separation. When he tried he would end up in a hot soapy shower thinking about putting on freshly starched cotton clothes. Someone should have warned him in Raleigh not to drink on the plane. Here he was in Mexico City, a mile high, still a bit dazed.

Three blond children, not more than five or six years old, obviously embassy kids, a little girl and two little boys, were playing house in and around a sort of blueprint design of squares and rectangles drawn with green chalk on the sidewalk. A solid block of taxicabs, more than the professor had ever seen, was passing on the Paseo de la Reforma.

Something about the broad boulevards and the taxi horns reminded him strongly of Paris, where twenty years ago he had spent his one sabbatical. The next year he had met his wife, who often reminded him that he had never taken her to Paris as he had promised. Or done any fun things. There was never enough money on his salary, she accused him, to do any fun things. In the late autumn air the feeling of déjà vu was so strong that he felt it was a dream, or a forgotten passage from a novel he was living through.

The two boys were now standing near him whispering, and the little girl was in the chalk-line house, busily sweeping, putting things on shelves, getting pots out of a stove only she could see, and washing dishes in the silent sink.

At a signal he did not notice, the small boys, giggling and full of themselves, marched slowly to the front of the house and knocked on the door. “Knock. Knock.”

The little girl seemed genuinely surprised. She came through the house, untying her apron and opened the door, drying her hands on the apron.

“Oh, there you are!” She was quite annoyed. “Late again, as usual. And furthermore you have brought a perfect stranger home to dinner.” Oh, she was vexed. “Without even asking. Without even calling!”

“Yes, my dear,” the little husband said proudly, full of his secret. “I would like for you to meet the man who owns the merry-go-round.”

As the boys entered the house, the professor glanced at his watch. He was still five minutes early. Enough time to walk to the far corner.

As he strolled up the dark gusty boulevard, he could still hear the high laughter of the children, and at the sound of their thin, excited voices his heart almost broke. After all, how were they to know (for they were still children), how could he have known she would run off with the man who owned the merry-go-round?

Poem August 2024

POEM AUGUST 2024

Steadfast

A lone tree fell in my woods

But it didn’t hit the ground

Or make that debated sound

It fell into the steadfast embrace

of another tree

With its outstretched branches free

They lean into each other

The broken and the strong

The living and the gone

It’s only with a passing breeze

And a creaking, crying bough

That they make sure we hear them now

— Kayla Stuhr

Kayla Stuhr is a Scottish visual artist, writer, and award-winning filmmaker.