Against the Grain

The Remarkable Life and Legacy of Master Craftsman and Free Man of Color Thomas Day

By Jo Ramsay Leimenstoll

In the furniture and woodwork he crafted for a region’s elite, free Black Thomas Day (1801-1861) combined his cabinetmaking talents with his personal interpretations of fashionable styles to create a distinctive woodworking idiom unique to the mid-nineteenth century Dan River region of North Carolina and Virginia. His remarkable legacy of furniture and architectural woodwork reveals a familiarity with popular pattern books, mastery of furniture-making techniques, incorporation of emerging technology, and expression of a personal aesthetic that elevates him beyond the role of a craftsman to that of an artist. With his great artistic autonomy, Day is one of a few free people of color to leave behind a substantial body of work, one that includes more than 200 pieces of furniture as well as interior woodwork in more than eighty houses.

Born in Virginia to mixed-race parents, Thomas learned the woodworking trade from his father, John Day. When Thomas was a teen, the family migrated from Virginia to North Carolina, eventually settling in Warren County. In 1821, Thomas left his father’s cabinetmaking shop to set up his own shop in Hillsborough. Just two years later he joined his older brother John’s shop in the bustling town of Milton where access to the Dan River and two railroad lines generated a thriving community of artisans and merchants. Although John subsequently left for Liberia to become a Baptist missionary, Thomas remained in Milton where he continued to build his cabinetmaking business, purchasing property in 1827 and establishing his reputation as an artisan. In 1830, Day married Aquilla Wilson, a free Black from Virginia, but she could not join him because an 1826 law prohibited free people of color from migrating to North Carolina. In an unusual response that speaks to Day’s importance within the community, sixty-one prominent white men in Milton and Caswell County successfully petitioned the General Assembly to permit Aquilla to move to North Carolina. Romulus Saunders, the state’s attorney general, endorsed the petition adding:

I have known Thomas Day (in whose behalf the within petition is addressed) for several years past and I am free to say, that I consider him a free man of color, of very fair character — an excellent mechanic, industrious, honest and sober in his habits and in the event of any disturbance amongst the Blacks, I should rely with confidence upon a disclosure from him as he is the owner of slaves as well as of real estate. His case may in my opinion, with safety be made an exception to the general rule which policy at this time seems to demand.

The petition was granted in late 1830, and Aquilla joined Thomas in Milton. During the decade that followed their household grew to include three children and eight enslaved people. Day was a husband, father, church-going Christian, and respected member of the community. He was also a gifted artisan and a clever businessman. As his clientele expanded and his business grew, he purchased more properties in Milton, eventually acquiring the prominent Union Tavern on Main Street to serve as his shop and residence.

Day benefitted from the economic boom-era in the Dan River region that sprang from the 1839 discovery of a process for curing tobacco with heat creating vivid yellow “Brightleaf” tobacco. As the wealth of white planters soared, Day was in the right place at the right time, ready to accommodate their aspirations for refinement and gentility. Many chose Day to express their status through his interpretations of the fashionable Grecian style of furniture that paralleled the emerging Greek Revival architectural style. A savvy entrepreneur, Day capitalized on the planters’ social network to establish the largest cabinetmaker’s shop in the state by 1850 — a shop with a diverse workforce of enslaved men, white and mulatto journeymen, and apprentices.

His furniture and woodwork were primarily crafted for the homes of wealthy planters and middle-class merchants, including such prominent citizens as physician and planter John T. Garland, attorneys Bartlett Yancey and Romulus Saunders, merchant John Wilson, and planters William H. Long, William H. Holderness, and Thomas M. McGehee. In addition, Day also received some institutional commissions, including furnishings for the Dialectic and Philanthropic Society Debating Hall at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He also fabricated the pews for the Milton Presbyterian Church where he and Aquilla were respected members.

Day’s early furniture reflects a familiarity with popular pattern books illustrating classically inspired pieces he skillfully replicated. Day was also quick to incorporate the emerging stylistic trends appearing on the national scene, including French, cottage, and Gothic influences. By the 1840s he adopted a more idiosyncratic design aesthetic that distinguished his work from his contemporaries and from the pattern books and broadside posters of the period. Day fabricated much of his furniture from imported mahogany, or he employed mahogany veneers over secondary woods. His repertoire included all the pieces needed to accommodate a genteel lifestyle, and his embrace of technological innovations such as a six-horsepower steam engine dramatically enhanced his productivity. Between his steam-powered shop equipment and large workforce, Day could rapidly produce orders even as large as Governor David Settle Reid’s 1855 request for forty-seven pieces of furniture.

Day’s custom-made cabinetry and furniture exhibit a powerful energy and a vocabulary of individualized motifs that define both form and detail. While his designs adhered to the principles of symmetry and balance, and utilized classical details, Day pushed beyond standard conventions with bold three-dimensionality, serpentine curves and exuberant ornamentation. The fluidity of his forms suggests a sense of motion that by contrast made the work of his counterparts appear staid. The popular S-shaped scroll motif is incorporated into many of his pieces such as the rocking chair arms and the mirror brackets of his open pillar bureaus. Day lightens the massiveness of Caleb Richmond’s sideboard with S-shaped pillars terminating at the base in scrolled feet, and he embellishes the mirrored gallery back with a pair of whimsical S-scrolls set on the diagonal.

Day often detailed his side chairs and rocking chairs as well as other pieces with ornamentation composed of scroll shapes, ogee and reverse ogee forms, and foliage motifs. While such shapes are certainly not unique to Day, he applies them with more vitality and three-dimensionality than his peers. In particular, Day’s distinctive whatnots with pierced galleries illustrate his use of the jigsaw to create positive and negative shapes. Still balanced and symmetrical, these playful serpentine shapes convey motion and whimsy as do the S-shaped scrolls that support each of the shelves.

The unique, signature lounge is the furniture form most closely identified with Thomas Day. It evolved from an upholstered lounge form popular in the early 1800s that incorporated a low back at one end. Day transforms this earlier model by suspending a slender backboard between arching rear pillars so it appears to float effortlessly across the length of the lounge and creates a complementary negative space in the open back below. Likewise, the side arm rails of the lounge mirror their shapes in both positive and negative forms.

Like his furniture, the distinct and innovative architectural woodwork of cabinetmaker Thomas Day emerged from a specific context of race and place as planters in the 1840s and 1850s expressed their gentility through new boom-era Greek Revival houses and front additions to earlier homes in the Dan River region. More than eighty houses constructed or expanded over a quarter century radiate out from Day’s shop in Milton on either side of the Dan River, revealing the volume and scope of his work. Six intact North Carolina houses illustrate Day’s fully articulated woodwork ensembles of the mid-1800s. Two were built as additions to older houses: the 1856 front section of the Bartlett Yancey House and the ca. 1855 side addition to Longwood (lost to fire in 2013). The other four properties are large Greek Revival period houses: the Holderness House (ca. 1851), the Friou-Hurdle House (1858), the Richmond House (ca. 1850), and the Bass House (ca. 1855). In the next decade, Day embraced the emerging Italiante style with lively sawnwork crafted for the exterior and interior of the Garland-Buford House ( ca. 1860).

Commissions from wealthy planters provided a springboard for Day to create his own artistic signature writ large through architectural compositions. Using staircases, mantels, niches, corner blocks, baseboards, and casings as his palette to sculpt interior spaces, Day developed a fluid, exuberant, idiosyncratic interpretation of the Greek Revival style adopted throughout the Dan River region — all the while operating within the legal and social systems that constrained free Blacks at the time.

Day brought the vivacity of the curving line to his woodwork in innovative ways that continue to amaze and delight. In his entrance halls, bold and varied S-shaped newel posts with tightly coiled spirals and sinuous curves spring from the handrails, all in sharp contrast to the straightforward turned newel posts in most houses of the era. Many of these houses typically have turned newel posts or the more traditional circular ring of balusters supporting a horizontal spiral that terminates the handrail. In contrast, Day rotated the relatively serene horizontal spiral 90 degrees and enlarged the vertical spiral to form the entire newel, conveying a sense of energy and motion that extends the movement of the ramped handrail into the entry hall. Day’s signature newel posts proclaimed the owner’s social status to all who entered.

Complementing his newel posts, curvaceous stair brackets at the end of the treads display fluid-lined variations on standard patterns. While most Greek Revival staircases incorporate decorative stair brackets, only Day’s utilized coordinated motifs to reinforce the S-shaped newel post statements, such as those he crafted for the Glass-Dameron House and Hunt House staircases.

Day’s mantels, the focal point of many a planter’s parlor, invigorated standard Greek Revival idioms with robust serpentine mantel friezes to create a sense of movement unlike the static paneled friezes of their counterparts. As seen in the Holderness House parlor, Day reinforced the hierarchy of the parlor as the most formal interior space by flanking the mantel with arched niches framed by deeply fluted moldings. Likewise, around door and window openings, Day installed bold casings animated by the shifting patterns of light and shadow on their deeply fluted surfaces. The undulating forms and sharply cut sawnwork characteristic of Day’s interiors play upon the tension between positive and negative space.

Like his furniture designs, Day’s architectural woodwork grew out of the framework of classical architecture, respecting formality, symmetry and hierarchy. To his interiors, Day brought fluidity and movement as he abstracted, distorted, rotated, intensified and distilled to transform that vocabulary. Day skillfully maximized and celebrated the fluidity of form as someone who knew the rules and understood how to break them.

The remarkable design aesthetic of his furniture and architectural woodwork speaks to us of the complexity of the life and work of Thomas Day — an entrepreneurial free person of color who crafted a remarkable legacy equally complex in its style and expression. His amazing tangible body of work continues to astound and inspire far beyond the Dan River region. Day’s work also reveals the enduring power and innovative evolution of his appealing aesthetic, an aesthetic ironically empowered by the most powerful and wealthy white citizens of his time and place.

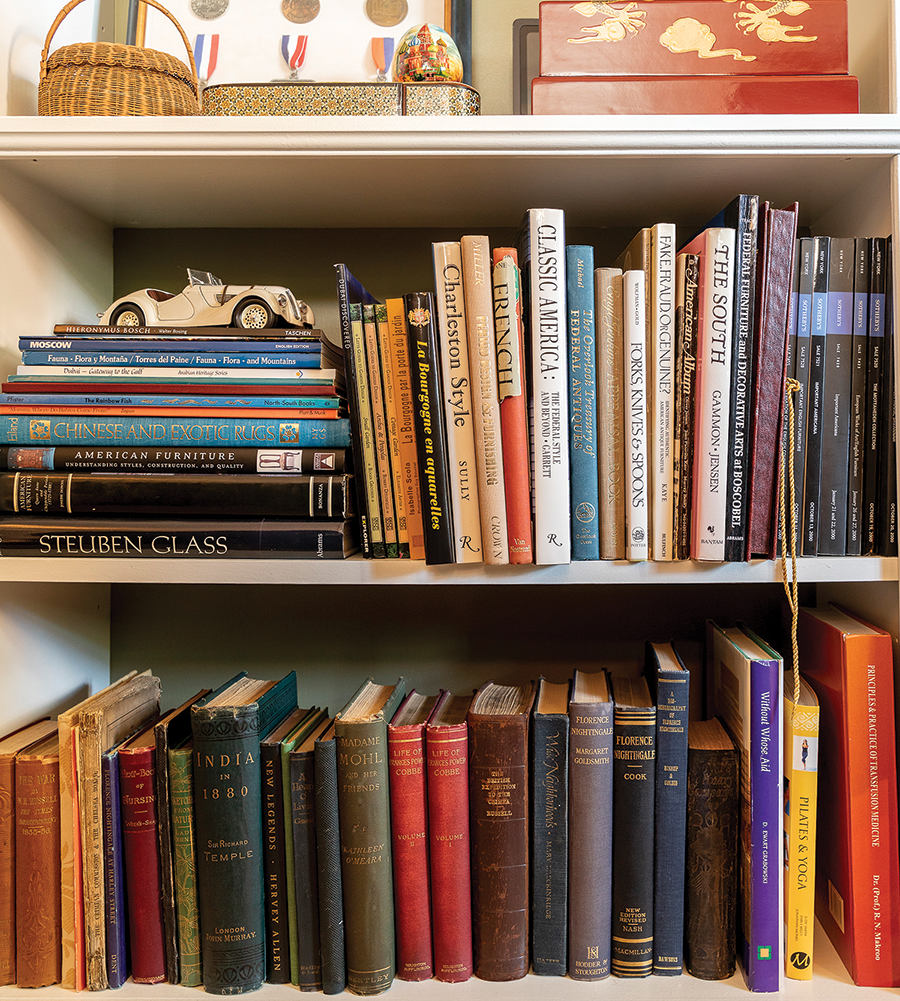

To Learn More

If you are interested in knowing more about Thomas Day, check out Blandwood Estate current exhibit, “New Perspectives on Thomas Day — Pairing Furniture by North Carolina’s Free Black Master Craftsman With Contemporary Pieces From Governor Morehead’s Blandwood,” April 1 through Sept. 30. The exhibit will generate conversations about the acclaimed free Black cabinetmaker and artisan. Displayed with Day’s furniture are pieces once owned by Gov. John Motley Morehead. According to Blandwood, the show also examines Day’s furniture in period rooms and “introduces new approaches to understanding the work of this master craftsman as a successful Black entrepreneur operating within elite white social circles.”

“This special presentation of Day’s furniture acknowledges his role in American history and speaks for the legacy that people of color gave Blandwood,” says Benjamin Briggs, executive director of Preservation Greensboro. “This exhibit is dedicated to a more equitable approach to understanding the experiences of these individuals who have been overlooked in the past.”

A National Historic Landmark, Blandwood’s mission as a traditional house museum is to interpret historical narratives related to North Carolina history, architecture and the decorative arts. The exhibit’s mission is to expand the traditional narratives around race, gender and class in mid-19th century North Carolina during the mid-19th century.

The Day exhibit is open from April 1 through Sept. 30, Tuesdays through Saturdays 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. and Sundays

2 p.m. – 5 p.m., with the exception of major national holidays. The last tour begins one hour prior to closing. Tickets are $8 at the door. OH

Reprinted with permission from Preservation Greensboro. Jo Ramsay Leimenstoll is a preservation architect and a Professor Emerita at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.