Christmas With Dylan

CHRISTMAS WITH DYLAN

Christmas With Dylan

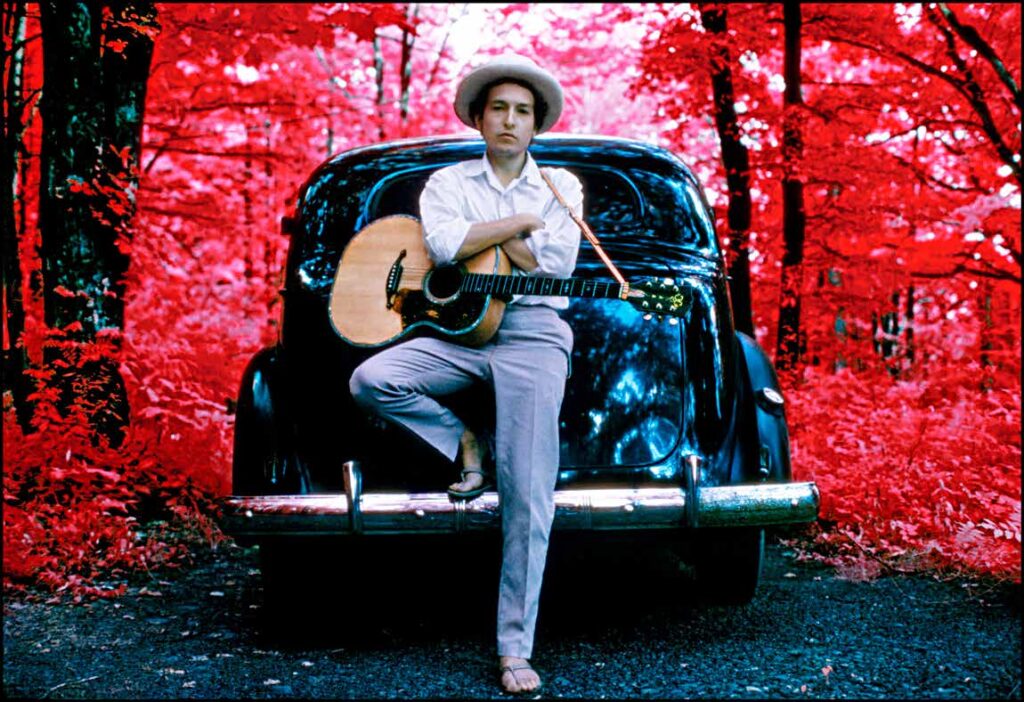

By Bland Simpson • Photograph by Elliott Landy

“A little more to the left.”

“No. It’s fuller around to the right.”

“Just try it my way and you’ll see.”

“Now the stand’s leaking.”

“Somebody’s liable to get electrocuted.”

“I swear you’ve got the best side to the wall.”

“I thought we’d be through by now.”

“You’re right — it was better back to the left.”

“Oh, God. I’ve already gone and tied it to the wall sconce.”

It was a few days before Christmas, 1968, and my family had gathered. The living room was filled with the intense, clean, resinous smell of the tree. Once we had it hoisted into place, we set about the bristly business of decorating. I was 20, and my mind was full of music. Withdrawing to the sofa, I thought: Bob Dylan wouldn’t be caught dead doing this.

“The angel’s crooked.”

“Let’s not have the angel this year.”

“Not have the angel?!”

I decided to make a pilgrimage to Woodstock, N.Y., to see Dylan. It didn’t slow me down a bit that I had little to tell the man except that I was inspired by his songwriting. To shake Dylan’s hand, that would be Christmas enough.

The next afternoon, with no more than 50 dollars, I set out. I was catching a ride north with two friends from UNC, paying my share of all the 26, cents per gallon gas we’d burn, and coming back south by thumb. Fifty dollars would be plenty.

This was really my second pilgrimage to Dylan and Woodstock. The first I had undertaken several weeks before, during Thanksgiving, and had abandoned outside of East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. I got cold and lost my nerve on a little-traveled high-ridge country road there, and I turned back. On the way home I caught a ride with a Black schoolteacher, who carried me all the way down 81 through the Shenandoah Valley night. We drank a beer together the last hour before he let me out, and agreed that things might be getting better between the races, or at least we hoped they were.

Then a trucker hauled me from Hillsville down the Blue Ridge Mountains. When we stopped at a Mount Airy diner and I didn’t order anything, he thought I was broke and made me let him buy me a cup of coffee and a chance on a punchboard. Back in the semi, he gave me some liquor, which I drank from a 6-ounce hillbilly souvenir jug he’d stashed under the seat. He let me off at 52 and 40 in Winston-Salem about 4 in the morning.

Immediately a hunter with an enormous buck strapped to the top of his Impala picked me up. A couple minutes later, he said: “Look, I hope this don’t bother you none but I got to hear some music.” He popped an eight-track of Johnny Horton’s Greatest Hits into the tape player, and the car was full of the songs I’d learned to sing by: “Battle of New Orleans” and “Sink The Bismarck!” and “North to Alaska.” The teacher and the trucker and the Horton-loving hunter made me think better of the pilgrimage business. I forgot the Stroudsburg cold and knew I’d try again.

It was several weeks later, the evening of December 10th, when we piled into my friend’s ’65 Rambler and went roaring up the three-laned U.S. 1, which is these days a ghost road just south of the Petersburg Turnpike. On and on, all night, the first of many deep and dreamless long-haul trips up and down the Eastern Seaboard. I was astounded at the size and magnificence of the great bridge at Wilmington, aghast at the dazzling lunar landscape, gas flares and chemical air of north Jersey. One of my more worldly companions gazed upon the scene and remarked with a combination of pride and disgust: “America flexing her muscles!”

From the George Washington Bridge, we looked out over the vast glare of Manhattan. In less than a year it would be my home, but that night it made me feel thoroughly out of place, for a few moments sorry I had even come. Soon it was past, and we were in the dark Connecticut country, and it was snowing lightly. I recovered my spirits; after all, I was on a mission.

They were driving me towards Storrs, Conn., to see the Hickey family, late of Chapel Hill, and coincidentally to perform a flanking maneuver to approach Woodstock from the north and east. The plan had been to leave me in New Haven where the big roads fork, but at the last minute my compatriots, who were bound for Boston, found it in themselves to veer off to the north and take me right into Storrs.

They left me at a gas station at first light, a gray dawning, 6 or 8 inches of snow on the ground and more still coming down. I showed up oafish and unannounced at the Hickeys’ home between 8 and 9 in the morning, four days before Christmas. They masked whatever annoyance they might have felt and greeted me affectionately.

All four daughters in the Hickey family were home for Christmas except the one who drew me there. She wasn’t expected for another 24 hours or so. No matter. The other three were going ice-skating that day, and so, now, was I. Most folks don’t forget their first time on ice-skates, and with good reason.

Sue did finally come home, and we had a lovely New England time that next day. It was brisk, and the sun was bright on the unmelting snow. She got over the surprise of my presence, commiserated with me about the Tower-of-Babel Christmas tree back home, and wondered what I would say to Bob Dylan, himself, when we met. After breakfast the next morning, she drove me out to the highway, and I was soon up at the Massachusetts Turnpike in the company of a Goddard student driving a Volkswagen with skis strapped to the back.

He was on intersession, he told me. He was going somewhere to ski for six or eight weeks, for which he would get academic credit. We drove west towards New York and the Hudson, and, before he left me off at the Saugerties exit, I had seen groves of chalk-white paper birches for the first time.

A couple of artists, a man and a woman, in a dingy old Pontiac, drove me from Saugerties to Woodstock. They said they were friends of Bob’s, and suddenly everything felt very chummy. The artists called themselves Group Two-One-Two, after the route number of the Saugerties-Woodstock road. A few years later, when I was living on the Upper West Side in New York, I would see a notice in the Village Voice about a show they were having down in SoHo and meant to ramble down and take a look. But the notice would stay taped up on the refrigerator until well past the closing of their show, and I would never make the trip.

Group Two-One-Two’s explanation of where exactly Bob Dylan lived was so convoluted that I stepped into a shop in downtown Woodstock, a bakery, and asked them. In moments I was tromping on out of town through a wood and up a hill towards something called “The Old Opera House.” Dylan’s driveway, the bakers said, was right across from it.

It was about 18 or 20 degrees in the middle of the afternoon, and I wasn’t used to such cold. I didn’t feel dressed for it, but I certainly looked like I was. I had on a Marine greatcoat from a surplus store south of Wake Forest, a slouch hat from a surplus store on Granby Street in Norfolk that I’d bought on my way to see Cool Hand Luke with my Virginia cousins, and a pair of snakeproof boots from Rawlins, Wyo., that I’d bought on my way to be a cowboy in eastern Montana. (You, or your beneficiary, said the card in the boot box, got a thousand dollars if you died of snakebite while wearing the boots, providing the snake bit you through the boots.) All this was practical and, back home in North Carolina, warm winter wear, though my mother lamented that I looked like something from the Ninemiles — a remote swamp in Onslow County down east. It hardly mattered here. In Woodstock, everyone looked like something from the Ninemiles.

Without my even thumbing for it, someone offered me a ride, and there I was at The Old Opera House. There turned out to be six or eight driveways next to and across from the place, no names on mailboxes, certainly no sign that said: “This way to Bob Dylan’s house.” I waited. About 20 minutes went by before a thin man in his 30s came striding up the paved road. He would have walked right past me, but I spoke up: “Excuse me, do you know which one of these driveways goes to Bob Dylan’s house?”

“This one.” He pointed at the one he was starting down.

“Thanks.” I fell in beside him, and we walked fifty yards or so before either of us spoke again.

“Is Bob, uh, expecting you?”

“No.”

“Hunh. I don’t know if it’ll be cool for you to just . . . go up to his house.”

This was discouraging, but what could I do? Go back to the bakery and telephone for an appointment? “I’ve come from North Carolina,” I announced.

“Oh.” He gave up, and we kept walking. A few hundred yards into the woods, the road forked, and he pointed towards a long low building of dark logs that looked like a lodge. “That’s Bob’s house.” Then he disappeared down the other fork.

In the driveway at Bob’s house were a ’66 powder blue Mustang and a boxy 1940 something-or-other with the hood up. Two men, one of them small and weedy, the other bulky and bearded, were working on the engine. I stomped up in my snakeproof boots, but neither of them looked up. After a minute or two of staring over their shoulders at the old engine, I finally said, quite familiarly, “Bob around?” The weedy man didn’t respond, but the big fellow gave a head-point at the log lodge and said, “Yeah.”

Sara Dylan answered the door, gave me a blank look, and closed the door. About two minutes later Bob Dylan himself appeared and stepped out onto the small porched entry. He wore blue jeans, a white shirt buttoned all the way up and a black leather vest, and he was very friendly and relaxed.

“Bland. What kind of name is that?”

A family name, I said. Then just to make sure he’d hear me right, he asked me to spell it.

“Bland. Well, I sure won’t forget that.” He talked in person just like he sounded on record in “The Ballad of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest.”

“North Carolina, that’s a long way.”

I agreed, but I wanted to meet him, shake his hand, tell him I admired his work, that I wanted to write songs myself.

“What did you want to do before you got this idea about writing songs?”

“I was going to go to law school.”

“Well,” he said, more serious than not, “country’s gonna need a lot of good lawyers. Maybe you ought to keep thinking ’bout that.”

This wasn’t what I had traveled hundreds of miles to hear. I started asking questions. Did he live in Woodstock all the time? Most of the time, he said, but he was thinking about moving to New Orleans. When would he have a new record out? In the spring — “I’m real happy with this one.” He was talking about “Nashville Skyline,” which he had just finished. I asked about a song of his the Byrds had recorded, a song I’d heard out in Wyoming the summer before. “Yeah, I know the one you mean, but I can’t call the name of it right now — it’s in there somewhere.” The song was the riddle-round “You Ain’t Going Nowhere.”

We talked along like that for almost 45 minutes, during which time I felt the cold acutely. Dylan was dressed in shirtsleeves, but he didn’t seem to notice the cold at all. He must have known my head was full of hero-worship, and he was kind enough to let my time with him be unhurried. The moment of my mission played out as naturally as the tide. I was immensely grateful, am grateful yet.

The pilgrim was ready to go home. I pulled my map out, unfolded it, and while we talked about what the best way to head back south was, the bulky fellow lumbered over from the old car where he and the weedy man had been working all the time. The mechanic ignored me, and I ignored him right back, which was easy enough: I had the entire eastern United States spread out in front of me. My mind was on the road, but I did want one last word or two with Bob Dylan. He gave Dylan a report on all the things that weren’t wrong with car, then said: “I think we can get it started if we hook it up to the battery charger.”

“Okay,” Dylan said. “It’s in the garage.”

“I got it already, and tried to hook it up, but even with that long cord it won’t reach. We need another extension cord.”

“Extension cord,” Dylan said, and looked past the big man at the old car. He thought about the request a few moments, then shook his head.

“Gee, Doug,” he said, “I’m afraid we just used the last extension cord on the kids’ Christmas tree.”