Nights of the Opera

NIGHTS OF THE OPERA

Nights of the Opera

Director David Holley tells timeless stories on the stage

By Ross Howell Jr.

Photographs by Lynn Donovan

What happens in the Greensboro Opera Company’s production of Gian Carlo Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors is magical. But it doesn’t happen by magic.

When David Holley, general and artistic director of the company and director of opera at UNCG, invited me to rehearsals last November, I jumped at the chance. After all — I hadn’t attended a rehearsal since playing clarinet in high school band practice!

So there I sit, in UNCG’s beautifully renovated and modernized auditorium, on a Tuesday night after Thanksgiving. The company is just two weeks from opening at the Pauline Theatre, located in High Point University’s Hayworth Fine Arts Center.

The scene at the rehearsal seems anything but magical: Individuals dressed in casual clothes are milling about the auditorium and on stage, chatting and laughing. I notice that the singer who plays Amahl’s mother is wearing knee pads. The stage lighting seems harsh, casting shadows and washing out colors.

An accompanist at a piano on stage is talking with a boy who’s leaning on a crutch, a wooden flute slung over his shoulder. That’s Amahl, of course, aka Thomas Burns, the 10-year-old soprano from the Burlington Boys Choir who’s playing the part.

For a few moments I speak with Greensboro native, John Warrick, a performer in the chorus. He tells me he received his musical part via PDF, learning it on his own long before rehearsals began.

Then, at a table next to the orchestra pit, a young woman seated with her back to the audience rises and turns. She has raven black hair that hangs down her back.

This is Hanna Atkinson, the stage manager. Hers is not a role that immediately comes to mind when you think of the opera, but you soon realize she’s indispensable. Opera has lots of moving parts.

“Rehearsal is open,” she announces. “Chorus should come to the stage. Kings should come to the bench.” She gestures to the row of four metal chairs upstage representing the “bench.”

Warrick heads off to join his colleagues.

The director and cast run through several scenes, and soon Irealize why Amahl’s mother is wearing knee pads. There’s a lot of lying down and getting up from “bed” before the kings arrive. But there are no beds, only the bare stage floor taped to indicate them, so the actors kneel or recline.

After a humorous singing exchange where Amahl tells his incredulous mother that he sees one . . . then two . . . then three kings knocking at their “door,” the kings make their entrance oneby- one and sit down on the “bench.”

The character Amahl is disabled, so through all the scenes rehearsed, Thomas must hobble about the stage on his crutch, dragging a foot.

“Thomas, your timing was perfect,” Holley says. “You brought them in perfectly.”

The kings are about to sing. Holley nods to the pianist, then raises his baton.

“Thomas?” Holley asks, craning his head around to look downstage. “Where are you going?”

Thomas is carrying his crutch in one hand, a sneaker in the other. He walks to the edge of the stage, drops the sneaker into the darkness, then hobbles back on the crutch to take his mark near the kings, having realized it’s easier to drag his foot in a sock across the stage instead of in a rubber-soled sneaker.

Holley nods and I smile. Too bad the grownups didn’t think of that.

The rehearsal continues. There’s a glitch when the kings enter from the back of the auditorium and miss the row they’re supposed to turn on to access the stage. The procession has to regroup and start all over again.

“Remember as you come in to watch my beat,” Holley says. “Don’t listen for it — watch, or you’ll fall behind the tempo.”

“And hit your marks,” he adds. “Otherwise, you’ll get all bunched up.”

The rehearsal lasts about two hours.

All the while, director Holley coaches, cajoles, encourages, praises. He reminds his singers to tell their choirs, church groups and friends to attend the performances. He reminds the kings that they’ll meet the following evening for practice.

Then stage manager Atkinson announces the rehearsal is closed. I feel as though I’ve been watching a documentary. And in my heart of hearts, I’m wondering, Will this turn out OK?

After very successful performances at High Point University, the company has returned for a final dress rehearsal at UNCG Auditorium, where they’ll present their closing performances of the season.

Even outside the building, there’s a completely different vibe. Lots of case-carrying orchestra musicians are making their way toward the auditorium, for one thing.

Lynn Donovan, the photographer for this story, lets me in the front door, along with a young cellist who’s unfamiliar with the cast entrance location at the side of the building. Donovan takes off to finish setting up her gear as the musician hurries across the lobby.

As I’m crossing the lobby, I see Thomas Burns emerging from a dressing room in full costume. A woman holds a crutch and wooden flute by the door. Turns out to be a happy surprise.

I recognize her — Patti Burns, lecturer of French at Elon University. We’d met, because I shared an office with her husband, Dan Burns, assistant professor of English, back when I taught part-time at Elon.

When I ask her about being a stage mother, we both laugh, and Thomas looks doubtful.

“Do I know you?” he asks.

“No,” I say. “But I was working with your father the year you were born.”

Thomas gives me a wary look and takes his mother’s hand. They head for the stage, and I find a seat in the audience, settling in for another night at the opera.

A few members of the cast have not yet retreated behind the curtain. I can hardly recognize their faces, since they’re in full makeup and costume. The kings have beards and flowing robes. The faux jewels in their costumes glitter.

The orchestra is invisible, though I can hear them in the pit warming up. I caught a glimpse of Holley as I walked in, but he too is now invisible.

A single trumpet player runs through scales. The strings are tuning. I can hear the strains of a harp, the muffled thumps of percussion. The violin flourishes run faster and faster. The brass and woodwinds grow louder. Then, suddenly, there’s silence.

At 7:01 p.m., the house lights go dark. Immediately, I hear Holley’s voice.

“One of the spotlights isn’t working,” he calls. I hear a voice in the wings respond, then watch as a big man ascends a ladder until he is out of sight.

I hear a clink, and the light comes on.

There’s a scattering of applause and laughter in the orchestra pit, and then, Holley’s voice.

“Let’s hear it for Scott Garrison!” he says. Garrison is the auditorium’s technical director.

There’s louder clapping, flourishes from the violins. The curtain rises.

The empty, garishly lit stage I saw at my first rehearsal is transformed, bathed in the deep blues and purples of night. There is a wall, a door, a bench. Rough-hewn pallets for sleeping. The set is bathed in warm, yellow light. A single star, the star the kings are following, shines brightly in the midnight blue firmament.

“Thomas, give me a G,” Holley says. He wants to make certain the boy has the right pitch for the Amahl solo they’re about to rehearse.

Thomas sounds the note and the music begins.

There’s still tweaking. Sound amplification for the first violins section is improved. Additional adjustments are made to the stage lighting. There are corrections in tempo, pitch and spoken lines. It’s a rehearsal, after all.

When the kings make their entrance from the rear of the auditorium — honestly — it’s thrilling. Voices booming, perfect tempo, perfect spacing. I hold my breath as they ascend steps to reach the ramp onto the stage, but no one trips on those long, beautiful robes.

Thomas’s soprano voice nicely resonates with the eagerness and purity of youth. The arias Amahl’s mother sings are beautiful and moving. And a pair of dancers, choreographed by Holley’s colleague in the UNCG school of dance, Michael Job, enhance the chorus’s welcoming celebration for the kings.

Later, Holley calls individual performers downstage, almost like a curtain call. Some musicians in the orchestra play short solos. The mood is celebratory. Then, rehearsal is over.

Holley tells me Amahl and the Night Visitors is the ideal opera to introduce people to the art form.

“It’s short, it’s in English, it’s got beautiful singing, it’s got a wonderful orchestra, it’s got stunning visual arts, it’s got dance, it’s got choral music,” he says. “It’s the perfect opera in miniature form.”

And it’s magical.

While I know that you’re just as excited as I am to see Greensboro Opera Company’s next performance of “Amahl and the Night Visitors”, you’ll have to wait until a new production is scheduled.

Still, in October, you can take advantage of a very special opportunity. The company is presenting “Don Giovanni”, with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte.

Holley tells me the production will be a “semistaged concert version,” meaning the orchestra performs on stage, rather than being hidden in the pit. The singers, in full costume, perform the opera downstage, right in front of the audience.

For those of you whose command of the Italian language is like mine, never fear — an English translation of the lyrics will display above the stage during the performance.

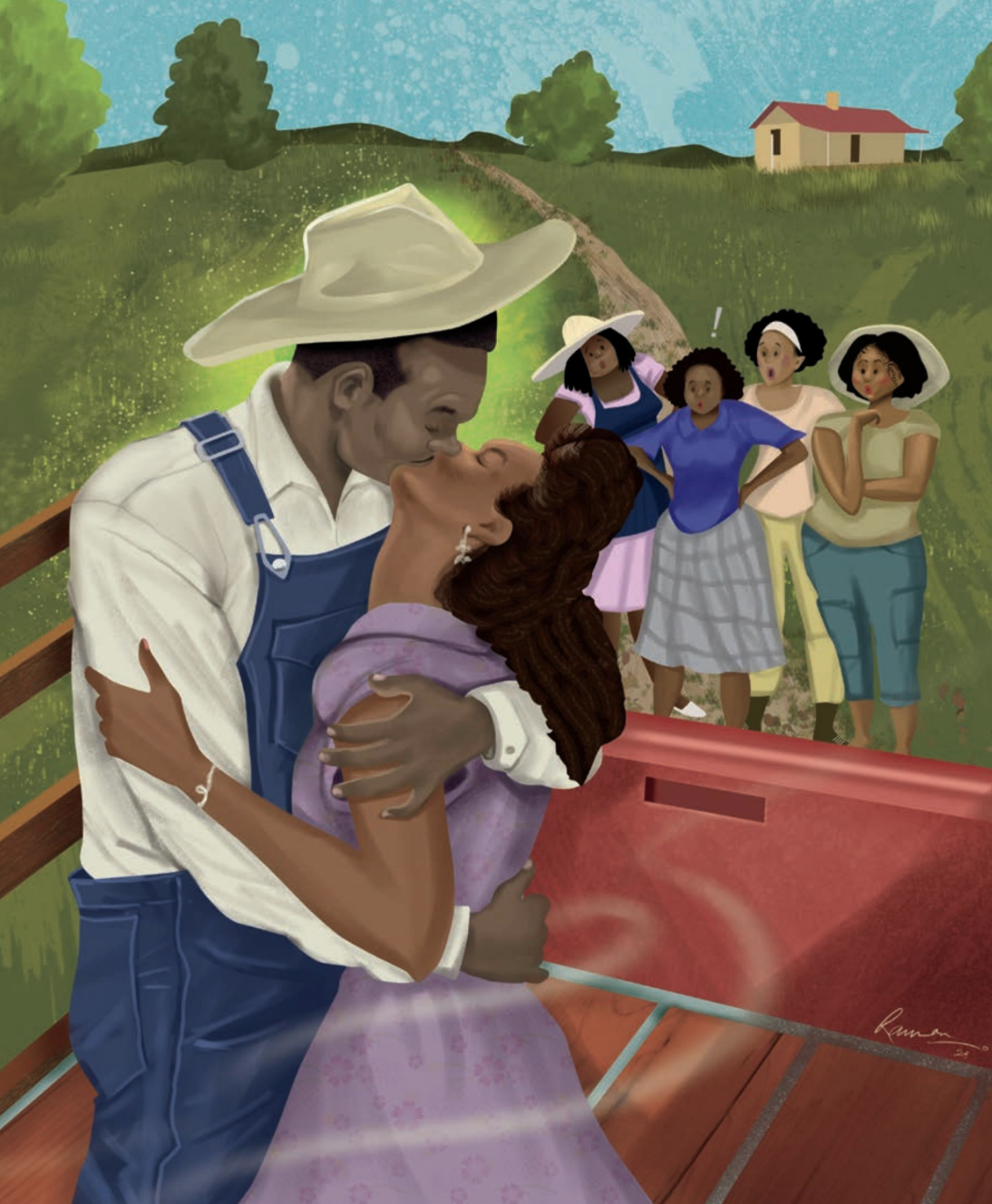

Based on the Don Juan legend of a Spanish nobleman who takes pride in his ruthless ability to seduce women, the opera premiered in 1787 in the city of Prague, with Mozart himself conducting. Sources describe the audience response as “rapturous and jubilant.” Some critics call “Don Giovanni” Mozart’s “opera of operas,” one of three masterpieces he created with librettist Da Ponte.

“It’s a very exciting production,” says Holley. “The story of “Don Juan” is timeless,” he adds. “You find versions of it in many cultures.”

Here’s the lineup of performers.

Sidney Outlaw returns to the Greensboro Opera to sing the title role of Don Giovanni after playing Jake in “Porgy and Bess”. Outlaw holds a B.A. in music performance from UNCG and a master’s from The Julliard School. He has performed internationally and is on the Manhattan School of Music faculty.

With a master’s of music from UNCG, Melinda Whittingon will sing the part of Donna Anna, a role she’s also performed with her home company, Opera Carolina, in Charlotte. She has sung with many operas, including The Metropolitan Opera in New York, and is an adjunct professor of voice at Davidson College.

Singing the role of Donna Elvira is Samantha Anselmo, who is pursuing doctoral studies in vocal performance and pedagogy at UNCG. Previously, she taught music and voice classes at the University of Southern Alabama. She has performed in two Mozart operas, “Così fan tutte” and “The Magic Flute”.

With a master’s degree of music in vocal performance from UNCG, Amber Rose plays the part of Zerlina in “Don Giovanni”. She performed recently in Opera Carolina’s production of “Madame Butterfly” and was the soprano soloist in Mozart’s Coronation Mass with the Masterworks Chorus of the Palm Beaches.

Another UNCG alum, Christian Blackburn, holds a master’s degree of music performance and is singing the role of Masetto, which he has previously performed with the North Carolina Opera in Raleigh. He has taken a step back from fulltime performing and runs a financial planning and advisory practice in Greensboro.

Donald Hartmann plays the role of Commendatore. He is both a UNCG alum and a colleague of Holley’s, earning his bachelor’s and master’s degrees of music, and serving as professor of voice in the college of visual and performing arts. He has performed more than 75 operatic roles in Europe, Canada and the U.S.

Holley is especially pleased that so many of his former students are returning to Greensboro to perform.

“That’s the beauty of the jobs I have,” he continues. “I wear these two hats — one as director of opera at UNCG; the other as general and artistic director of the Greensboro Opera Company.” In these roles, Holley not only trains young people who aspire to careers as singers, but also hires professionals to perform with the Greensboro Opera.

“Almost all the singers who are doing “Don Giovanni” in October came through my program or are colleagues,” Holley says. “I would say the UNCG College of Visual and Performing Arts is the flagship institution of music in North Carolina.”

Holley muses for a moment.

“You know, opera in this country has a stereotype of not being accessible,” he continues. “People think of it being the fat lady with the spear and the horns and that’s not what it is.”

“Opera is the greatest storytelling on stage,” Holley says. “That’s what we do. We tell stories. We just happen to put it in a context that uses beautiful music, and music speaks to your soul in a way that words by themselves cannot.”