Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

Something about homemade jams, pickles and syrups feels sacred and primal. As if linking us to a time when we worked with the Earth and grew our own food and baked our bread from scratch. Certainly they suggest a slower pace of life, one perhaps many of us glimpsed during stay-at-home mandates this year. And like anything homemade with wholesome simplicity and the freshest ingredients available, they always, always taste better than store-bought. We found four local home goods makers who are keeping the art of DIY alive and well, either for practicality or, more often, the simple joy of it.

Mary’s Pretty Good Jams

Sweet Dreams Are Made of This

By Billy Ingram

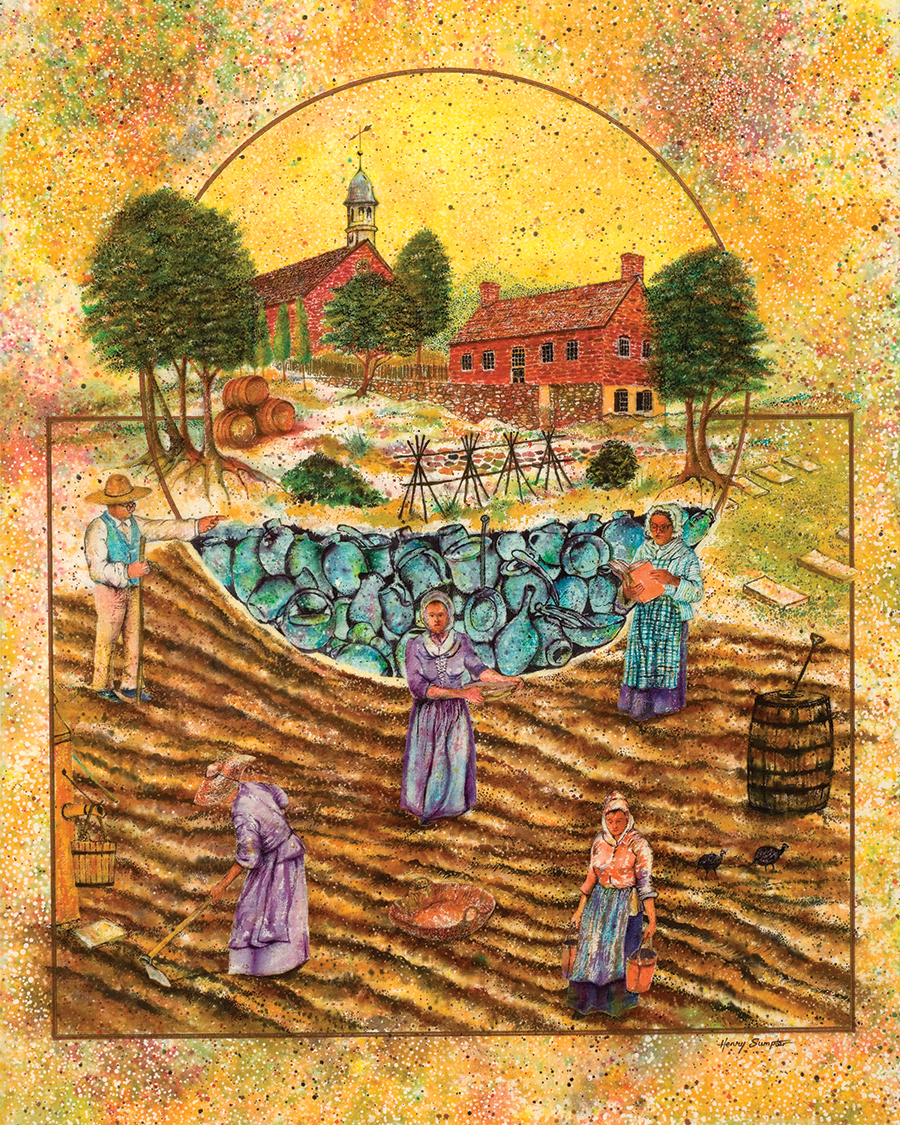

“What I’ve discovered is, if you make jam the same day that you pick the berries, it yields the best flavor. So that’s what I do,” says Mary Perko who, for over 40 years, has been making jams and other confectionaries the way Great-Grandmother did. Mary’s Pretty Good Jams — which include, to name a few, strawberry, black & blueberry and spicy peach flavors — are the finest nectarous spreads money can’t buy. Mary gives her flavorful fruit preserves away.

Six years ago her husband Dana was transferred from Alabama, where they’d lived for 20 years, to Greensboro. “I struggled a bit with homesickness,” Mary says. “What grounds me is doing what I did in Alabama, making jams, cooking, baking and then giving it all away.”

From the very beginning, ingredients have been locally sourced. “I’ve been fortunate to find strawberry fields in Kernersville along with blackberries, blueberries and peaches at my favorite of favorites, Blueberry Thrill Farm in Gibsonville.” Mary calls venturing out to the farm her counseling session. “Picking for me has been somewhat of a ‘zen’ experience. It’s quiet, there are no cell phones, you’ve got the birds chirping, blue skies and all of this bountiful fruit that is just absolutely amazing. I can pick ten gallons of berries in an hour or so.”

Recently she’s added sweet and tangy chow chow to her repertoire with yellow squash, zucchini, onions and jalapeños grown by nearby Smith Farm, Ingram’s Farm and Parsons Farm. “I am also part of the CSA program at Guilford College. That’s been my source for peppers.”

Mary’s Pretty Good Jams has developed quite a following over the decades. Last year over 300 Mason jars of ambrosial delight made their way around the U.S.A. “This year I’m about at that level now and it’s not even Christmas,” she said in October. “The recipients are friends back in Alabama and around the country, neighbors, former neighbors and my coworkers.” For Mary, there is no greater reward than seeing others enjoying fruits of her efforts. “It’s just something I enjoy doing,” she says. “Some days I think, ‘Should I start selling these at the Farmers’ Market?’ And I might, but I’m not sure how many people would spend six bucks for a jar of jam.”

Not everyone gets the golden ticket. Should you discover one of Mary’s Pretty Good Jams under the tree, Santa obviously thinks you’ve been very good this year.

Elderberry Magic

Helping people heal with Syrup and More

By Jim Dodson

Jennifer Zullo is a woman with a passion for helping people, as evidenced by the pleasure she derives from her two jobs.

Her day job is coaching college students with learning differences at Guilford College, High Point University and Greensboro College, using her years of training and work for social services and the high court system of the British Government to improve the lives of young people facing challenges.

“It’s very rewarding work,” Zullo confirms, “helping young people unlock their potential and find their way through college. But my most fun job is what I do almost every Monday.”

That’s when this energetic mother of two young sons spends five or six hours in the community shared-use kitchen on Clifton Road. As part of the Out of the Garden Project, the Triad’s most successful nonprofit feeding program, she makes and bottles her homemade Syrup and More Elderberry Syrup, a natural remedy for colds, flu and general nutritional health that has developed a passionate following of its own over the past five years.

The idea was born in her own home kitchen in Greensboro when she decided to find a natural way to improve the immune systems of her own young sons, Aaron and Abram. “I’d been reading about the benefits of organic elderberry syrup and had a friend in Florida who made her own. That inspired me to do my research and start working on recipes of my own.”

The one she eventually developed is a delicious syrup that combines both organic American and European-grown elderberries with locally sourced raw honey, rose hips, hibiscus and a variety of spices well known for their healing properties like clove, ginger and cinnamon. Elderberries have long been considered a powerhouse boost to a healthy immune system, slam full of vitamins A and C plus high levels of iron, a traditional winter remedy for colds, flu and allergies.

Her next step was to go through the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market’s innovative Kitchen Connects GSO program and gain certification with the Department of Agriculture.

Her mission to produce a delicious high-quality syrup that was also priced below other elderberry products on the retail market was compatible with Out of the Garden’s work to ease food poverty across the region.

“The reason I do that is because I don’t think we should have to lobby for health care when we already pay a fortune for it,” she says, pointing out that her organic vendors honor this noble goal by giving her a discount on everything from elderberries to honey, thus keeping the retail price down.

“I love making this syrup, and I love the idea of helping people,” she adds. “I would probably give it away if I could.” She produces anywhere from 50 to 100-plus bottles of elderberry syrup per week and sells every bottle she makes.

With demand on the rise and winter on the doorstep, you can find Jennifer Zullo’s marvelous elderberry syrup at the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market, All Pets Considered, Sunset Market Gardens in Reidsville, Black Dog Home & Café in Jamestown, Local Roots Coffee Bar in Kernersville, Pleasant Garden Country Market and The Budding Artichoke in High Point.

For more information and a complete list of locations, visit www.syrupandmore.com.

Pincha DryRub

Because it’s good on everything

By Ashley Wahl

Perhaps this isn’t the first origin story to have started inside of a Virginia Tech frat house in the 1970s, but for Kernersville resident Mark Stoehr, it’s certainly the most memorable.

Stoehr, whose name is pronounced like “grocery store” (insert his slight Southern drawl), recalls sharing a house with his fraternity brothers, cooking supper and cleaning the dishes once a week.

“I kept pulling down all the spices I used for making hamburgers or whatever I was cooking, and one of my brothers finally said, ‘Why don’t you save yourself some trouble and mix them all together?’”

Thus, Pincha DryRub was born.

Of course the recipe has evolved since Stoehr’s college days, fine-tuned years later when he started cooking whole hogs. Now he’s got his dry rub down to a science: Herbs (sage, sweet basil, rosemary, cilantro, dill weed, marjoram and thyme), spices (paprika, cayenne, chili powder and black pepper) and vegetables (ground celery, granulated onion and green bell pepper), plus ginger, turmeric, garlic powder, mustard seed, sunflower oil, sugar and salt.

The label suggests using Pincha for meat, stew and sauces, but Stoehr says you can rub it on anything and everything you cook, which he does.

It’s not too hot, but heat isn’t the point. A good dry rub should enhance the natural flavor of the meat, not distract from it.

Throughout his 33-year career as a product engineer for Analog Devices Inc., Stoehr designed computer chips and their test systems. Pincha DryRub was a side hustle, more a labor of love than necessity. But the demand was there. Mostly he sold it to his colleagues.

Three years ago, following his retirement from Analog Devices, Stoehr turned all of his attention toward Pincha. He wanted his rub in stores, and so he first pitched it to the owner of Musten & Crutchfield Food Market in Kernersville, where he frequently shops.

“He didn’t have anything like it,” says Stoehr, “and so he bought a case of it. Now he usually buys a couple cases a month.”

Pincha DryRub is currently available at over 20 locations in North Carolina and Virginia, including shops in Kernersville, Colfax, Browns Summit, High Point, Winston-Salem and Greensboro. He sells the largest volume to The Extra Ingredient at Friendly Shopping Center and Gourmet Pantry in Blacksburg, Va., not far from the old frat house where it all started.

He convinces stores to carry his rub by doing what he’s done since college: He cooks for people. Usually chicken or hamburger. Because when you experience Pincha the way it’s meant to be experienced, says Stoehr, it sells itself.

And for the vegetarian?

“It’s great on vegetables,” he says.

Take an onion, he suggests. Scoop out the middle. Add a bouillon cube (obviously vegetable broth, although that’s not what Stoehr would use), butter and a pinch of Pincha.

“Wrap it up in foil and cook it for an hour,” says Stoehr.

In other words, let the dry rub speak for itself.

Pincha DryRub is available at The Extra Ingredient in Friendly Shopping Center, Gate City Butcher Shop, Town & Country Meat and Produce, and Al Aqsa Meat Market in Greensboro. For a complete list of locations and more information, visit pinchadryrub.com.

Cookie Gurlie

Pure joy — and ingredients — in every bite

By Ashley Wahl

It’s impossible not to smile when you see Cheryl Pressley at the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market on Saturday mornings — and not just because she’s the Cookie Gurlie. It’s the joy in her eyes. The glow of a woman who is here doing what she loves.

Cheryl Pressley just might have been put on this planet to bake gourmet cookies.

Gourmet cookies, folks.

Her trademark slogan — A balanced diet is a cookie in each hand — is the gentle nudge one just might need to hear when trying to choose between the Ginger & Mo, for instance, and the Alfajore (that’s Latin American shortbread filled with homemade dulce de leche).

You can’t argue with that.

And given that her ingredients are the freshest and purest she can find — we’re talking unrefined pure cane sugar, spices from a local vendor, eggs and butter from local farms and, when in season, fresh berries and figs grown right here in Greensboro — you’re going to want that second cookie.

If Pressley had to pick just two of her gourmet creations forevermore (luckily she doesn’t, but she kindly played along), she would have a Chocolate Dippity Doo!! in one hand, a Not Yo’ Momma’s Chocolate Chip in the other.

All the best cookies have stories.

Why chocolate chip?

“When I was a kid, probably like most kids, that was the first cookie that I attempted to bake.”

She had seen what Wally Amos, as in Famous Amos, was doing and thought: If he can make cookies, then I can too.

Her family said hers were better.

“But, you know, they love me,” quips Cheryl.

As for the Chocolate Dippity Doo!!, a customer favorite studded with dark chocolate chunks, toffee and walnuts, dipped in dark chocolate and “finished with a sprinkle of Mediterranean sea salt,” this was the cookie that awakened Cookie Gurlie as we know her.

One of Pressley’s relatives had recently undergone chemotherapy and experienced what’s called taste changes.

“I was trying to think of a flavor combination that would excite her taste buds,” recalls Pressley. She made what was essentially a Chocolate Dippity Doo, but something was missing. Then she remembered her grandma’s advice: You always have to have a little salt with your sweet.

“The salt really balanced the sweetness,” says Pressley.

And that’s when she added the double exclamation points to the name, which you can hear in her voice.

Baking cookies for her cousin-in-law allowed Cheryl to play with wild flavor combos. She shared her creations with friends and family, who gave her feedback. She fine-tuned her recipes.

When her cousin-in-law died six years ago, Pressley thought her cookie adventures were over. But then something unexpected happened. She started getting calls from people requesting cookie orders. Like, lots of calls.

Cookie Gurlie became a business in what felt like the blink of her sparkling brown eyes.

Cheryl now bakes up to one thousand cookies a week. She says the best part of her business is the connections she makes with her customers.

For many, her cookies unlock childhood memories.

“People share their stories with me,” she says.

As the holiday season nears, you can expect to find year-round Cookie Gurlie favorites like Chocolate Dippity Doo!! and Ginger & Mo (made with black strap molasses and topped with black and white cracklin’ sugar). But save room for her ineffable sweet-potato cheesecake — it’s not a cookie, but nobody says a balanced diet excludes cake. OH

Find Cookie Gurlie at the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market, 501 Yanceyville St., Greensboro, every Saturday from 7–11 a.m. or online at www.cookiegurlie.com.