A short oral history of Piedmont Airlines

By Billy Ingram

Let’s face it. Commercial flying has devolved into traveling in a cloud-bound cattle car. Not only is there no decent cud to chew on, but the onboard entertainment too often consists of free-for-alls up and down the fuselage, flight attendants overwhelmed by Karens and Kevins prone to engage in unrestrained, unctuous behavior. Blanket or last-minute cancellations, overbooked flights, intrusive security measures, soaring ticket prices, interminable terminal wait times, claustrophobic accommodations — all adding up to an overall unpleasant experience.

That wasn’t always the case. There was once a homegrown airline with a can-do spirit, piloting truly friendly skies. A bygone era when flying was a genuine pleasure, when stepping through the airplane door made you feel as if you’d already arrived home. Piedmont Airlines was the vision of Winston-Salem entrepreneur Thomas Henry Davis (1918-1999), who transformed a ragtag collection of nearly obsolete aircraft into a world-class operation — and perhaps the most beloved air passenger carrier of all time. But don’t take my word for it.

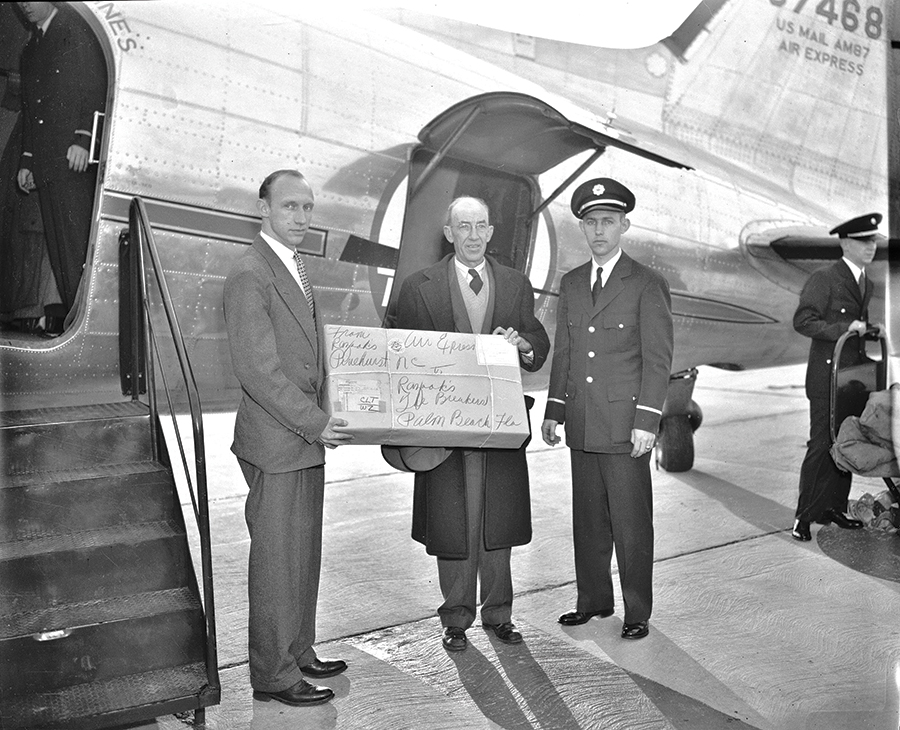

Chris Runge, curator for Piedmont Aviation Historical Society: Piedmont Airlines started out as Camel City Flying Service in Winston-Salem. Piedmont CEO Tom Davis was asked to purchase [the company] in 1939. He changed it to Piedmont Aviation in 1940, they trained pilots for World War II — both in Winston and in Greensboro. When the war was over, he had all these employees, so he started an airline because he didn’t want to lay off all these people. They started out with three DC-3s. The first flight was February 20th of 1948. They were known as the puddle-jumping airline.

Capt. John Williams, Piedmont Airlines pilot from 1979–1989: Any time you’re a small-scale operation like that, they refer to [you] as a puddle jumper. In the beginning, Piedmont didn’t go too far away from North Carolina. The farthest they went on their first flights was Cincinnati.

Richard Eller, author of Piedmont Airlines A Complete History, 1948-1989: In the ’60s, Winston-Salem expanded rapidly due to several large industries that were really much bigger than the city itself. But they made Winston-Salem so much more important. Think about R.J. Reynolds [Tobacco Co.], which had been there for a very long time; Krispy Kreme was there; TW Garner [the makers of Texas Pete]; Hanes. And Piedmont was one of those really big companies.

Chris Runge: Piedmont made Winston-Salem the busiest airport in the state in 1963, based on departures. It had a huge impact on the city. There was the headquarters, a reservation center . . . They had a fabric center, a woodworking center, Piedmont Aerospace Institute. It was a really big deal.

John Williams: First off, it was not a job. Practically everybody knew everybody. Practically everybody knew everybody’s family. Who was sick, who’s going on vacation. It wasn’t a busybody, put-your-nose-in-somebody-else’s-business thing. It’s just like you were working with your family. That term, family — that needs to be stressed because after having worked for USAir, US Airways . . . American and Delta, none of them even vaguely resembled Piedmont Airlines. They were overly businesslike, very cool and efficient. At Piedmont, you were pretty much on a first-name basis with everybody.

Holley Greene Rogers, Piedmont Airlines flight attendant from 1983-1989: In the early ’80s, the job market was not that great. Every 23 year old in North Carolina was trying to get a job as a flight attendant with Piedmont. I thought I’d just do it for a few years and ended up staying for 22 years (with Piedmont and then US Airways). It’s not really a career choice; it’s a lifestyle.

They still allowed smoking when I got hired in ’83. I had to keep my uniform in a separate closet — it stunk so bad from the smoke. Flight attendants work hard today, but they don’t serve meals like we used to. We used to sling out a hot meal between Greensboro and New York, give everybody a hot towel, give them two drinks, clean up that cart and land. We really worked but it was still so much fun.

Sharon Carroll Williams, Piedmont Airlines flight attendant from 1984-1989: It was all about attractiveness when I started. Flight attendants had to be at least 5′ 3″ and you couldn’t wear glasses. They weighed us. You had to be a certain weight to get the job, and we never knew when we opened the door of an aircraft whether our supervisor would be standing there, which meant it was time to get weighed again. In the 1990s, airlines stopped doing weight checks because it was considered discrimination. The airlines found a way around this. During our yearly FAA [evacuation simulations], they made us exit through the smallest window, so that became the way they evaluated your weight.

Before I started, you could not be married and be a flight attendant. That was a strict rule. If you got married as a flight attendant in the ’60s and ’70s, you had to quit your job.

Holley Greene Rogers: The longer you stayed, the more seniority you accrued. You’re given a pay number the day you’re hired and that’s your number forever. That dictates whether you get on a flight or whether someone senior gets on ahead of you. The pilots never wanted to leave an employee at the gate. Something Piedmont would do, they’d say, “C’mon, you can ride jumpseat in the cockpit.” You would never see that with an airline today.

Chris Runge: The 727 has what you call your rear air stairs — the stairs that come out of the back of the plane. If a passenger missed a flight and the plane was halfway down the tarmac, the agent would call out to the plane, they’d stop, the pilot would drop the air stairs. The passenger would run out on the tarmac, jump up the back of the plane and they’d lift it up and go. Their motto was “Don’t leave anybody behind. Ever.” And they didn’t.

Richard Eller: The pilots were seemingly having the time of their lives. Because they flew to the same places a lot, that created a kind of family between the pilots and flight attendants and the people there. They stayed in the same places, they partied in the same hotels. There was a camaraderie.

Holley Greene Rogers: Every pilot I ever flew with was a gentleman. I never had any Piedmont pilots harass me in any way whatsoever. But they would tell some off-color jokes.

John Williams: Yes, we would share an off-color joke every once in a while — if you knew that nobody was going to get offended. But for the most part, we were encouraged to be southern gentlemen. We had a good time. There’s no question about it . . . but it was very businesslike in the cockpits and on the aircraft.

Capt. Lori Cline, Piedmont Airlines pilot from 1984-1989: I was not just the youngest female captain ever. I was the youngest captain, period. You cannot command an aircraft as a captain until you’re 23. I was able to get my certification on my birthday and I flew that day with my fourth stripe. So, conceivably, there can be no one younger. That was when I was with Atlantis Airlines [Eastern Express].

I was about the 14th . . .16th woman pilot hired at Piedmont. So, there had been many trailblazers before me. Of course, there were always pilots that had never flown with a woman before. It’d be like, “Oh, another woman in my cockpit.” That was a difficult time. They wanted to not like women pilots, but then, when they saw that you were professional and you were a nice person it’s like, well OK, maybe this isn’t so bad.

Holley Greene Rogers: Tom Davis understood that your employees are the greatest asset you have, and he treated us like gold. His son was a pilot and his daughter was a flight attendant for Piedmont.

John Williams: I flew Tom Davis a lot. He had a home in Wilmington, and we would fly from Winston or Greensboro, fly him down there as a passenger all the time. The thing that amazed me about him was — and I’m sure he probably had help — but he would come through the cockpit and greet everybody by their first name. That impressed me, that he went to that detail. He was quite the gentleman and scholar, just a great guy.

Chris Runge: Tom Davis made a point of knowing everybody’s name and that’s the one thing everyone will always tell you: that “he always called me by my name.” What they didn’t know was that, before he would enter a station on the system, whether it be Greensboro or Fayetteville or Richmond, he had a little black notebook and he would check it. Because the last time he was there, he would write down “tall red hair, David. Short black hair, Joe.” He would go over that list, refresh himself with their names.

Lori Cline: Piedmont was very progressive, even for the ’80s. There’s a famous picture of myself in the right seat of a 727 with Bill Wilkerson, who is a captain of color, and a young flight engineer who couldn’t have been 21. We took [the photo below] in 1986. That was very progressive for an airline to have an African-American as a captain and a female co-pilot on a 727. We didn’t take the photograph because it was anything we were trying to document. Captain Wilkerson had just gotten a new camera for his birthday and he said, “Let’s take a picture.” We re-created it for the 70th anniversary celebration of Piedmont Airlines in 2018 and presented it to the N.C. Transportation Museum.

You look back at it now as airlines struggle for diversity today and, gosh, Piedmont was doing it back in the ’80s. I think that says a lot about Tom Davis’ vision for the future of what the airline flight deck components should look like.

Chris Runge: One of the things that employees thought was most special at Christmas was that everyone got a crisp, brand-new $100 bill from Mr. Davis. He would deliver it to them personally. Eventually the airline grew into a major carrier with 24,000 employees, so he couldn’t hand deliver each one, but you do the math — 24,000 employees times a hundred bucks.

Lori Cline: One year we got $100 for Christmas and a check to pay for the taxes. Turkeys at Thanksgiving. They took good care of their people.

Holley Greene Rogers: I’m a baby at Christmas. I like to be home with my family. I only had to work my first two Christmases because they hired so many people after me. I usually had to work New Year’s Eve, but I didn’t care about that. It would be a little hard to be in a hotel with your crew, but the crew would always do something, somebody would bring some good food and cookies and we’d just make the best of it, you know? Sometimes you might be in New York or some lovely town with beautiful lights and you could walk around and see the sights. It was over before you knew it.

Lori Cline: I loved to fly Christmas. I didn’t have children at the time, so I would purposely fly Christmas because I always thought people with kids should be able to get to stay at home. You brought gifts for your crew, you brought a little Christmas tree, decked out the galley and decorated as best you could. And everybody would be in such great spirits and have a great layover. If you couldn’t be with your at-home family, you were with your airline family on a really special day.

John Williams: I only had one Christmas that I worked. That was just by pure happenstance. Lots and lots of New Year’s, but I volunteered to do those. A lot of people like to party on New Year’s. I never did, so I flew a lot of those flights. Got a good night’s sleep in a hotel room.

Chris Runge: Piedmont was named “Airline of the Year” in 1984. They started service to Los Angeles on April 1st of that year. You would fly from Greensboro to Charlotte and have a brief layover. That’s when they would board all the passengers who purchased the nonstop flight to L.A. They needed what was called extended range aircraft, the 727-200.

But they weren’t ready. They used the regular 727, which didn’t have the capacity to go all the way across the country without refueling. So they’d have to stop at places like Tulsa and, because they didn’t give the passengers nonstop service, at the end of the flight the pilot would come around and pass out $100 bills to first-class, $50 bills to coach. People would get off the plane and say, “You know, if you do this all the time, we don’t care about Tulsa. We’ll fly with you every time we come out here.” They were just so big on customer service. I mean, that was number one.

Lori Cline: Without a doubt, my favorite airplane of all time was the Boeing 727 for Piedmont Airlines, which was a workhorse for the industry during the ’70s and ’80s before it was retired for being considered inefficient, fuel-wise, due to its third engine. And to this day, before I retire, if I could get to fly one airplane again, it would be that classic Cadillac one last time.

John Williams: The 727 series was just a horse. It was a great flying airplane. I also liked the 767, both of them are Boeings. You can pretty much say any of the Boeings were tip-top, number one, but my absolute favorite was the 727.

I’m lucky. I’ve never had an engine shut down on its own. Never had a fire while airborne. Our training, by the way — I need to say this out loud — our training department fully equipped each and every pilot with all the tools necessary to react to anything that happened. They taught you every nut and bolt on the airplane. Our 727 training was, if anything, overkill. Components you couldn’t touch, that you couldn’t access, but you knew what it was, where it was and how to treat it in case something went wrong. The training these days? The emphasis on detail has been detuned.

Lori Cline: Piedmont’s flight training was known to be one of the more difficult schools. I remember watching an entire slide presentation on the windshield wiper assembly and the nuts and bolts that held the windshield wipers onto the windscreen and thought, “Oh, my God. It was like a 20-minute presentation on the windshield wipers. We haven’t even gotten to the engine yet!”

Sharon Carroll Williams: I tell this story in my book [Life at 36,000 Feet: Where Faith and Fear Connect]. One close call happened in Roanoke where the Captain couldn’t determine whether the landing gear was fully locked into position before landing. When landing gear fails to hold and an aircraft needed to “belly in” for a landing, it meant an increased risk of fire. As the captain explained the situation over the intercom, the passengers got really quiet. So we had to ready the cabin for an emergency landing, which included instructing everyone in the brace position, then we went about securing everything. When I looked out the windows, I could see all the firetrucks ready with the foam. When the landing gear held tight, the passengers erupted into cheers and applause.

Holley Greene Rogers: Piedmont was bought by USAir in ’89, but mostly everybody I flew with was hired by Piedmont. It was a completely different attitude. It wasn’t the same at all. We always hoped it would be Piedmont buying USAir, but stockholders wanted to cash in, so that’s how it turned out.

Richard Eller: They always called it a merger, but it really wasn’t. The old adage that some people quoted to me was that, “We’re going to blend cool Northern efficiency with warm Southern hospitality,” and that didn’t work. In those last couple of years, after USAir bought Piedmont, they tried to run it as two separate airlines. That didn’t work. People used to refer to them as Useless Air.

Chris Runge: August 4th of 1989 was the last flight. That’s when the real dismantling of Piedmont began. USAir started to institute their policies and their way of doing things. They ended service to the smaller cities. And gosh, they just . . . I mean . . . morale sunk, passenger complaints soared. They went from first to worst in so many categories like on-time performance, lost baggage . . .

Richard Eller: Every person I interviewed for the book and the documentary [Speedbird: The History of Piedmont Airlines] truly regarded Piedmont as a family. One of the pilots said that he was asked one time, “What are you going to do for Christmas? You going home to your wife and kids? Or are you going to hang out with your family?” Meaning the airline.

A couple of pilots said they told Mr. Davis that, if he wanted to start another airline someplace else, they would quit their jobs and follow him. It’s a testament to the kind of company that Tom Davis built with Piedmont, how loyal these folks were.

Rick Amme, news anchor WXII, Aug. 4, 1989: I said it all week and I’ll say it again: The Piedmont will not be the same without Piedmont Airlines. OH

Billy Ingram’s book Hamburger2, (mostly) about Greensboro, is available as a free PDF for your Kindle or other devices at tvparty.com/1-hamburger.html

Photographs Courtesy of the Piedmont Aviation Historical Society