Scents and Sensibility

The loss of smell brings an unexpected gift

By Bridgette A. Lacy

Maybe I should have taken more time to smell the fragrant rosemary in my yard. Or I should have soaked in my almond-scented bubble bath more often. Perhaps, I should have savored the sweetness of my Uncle Jack’s red roses instead of assuming they would always be there for me.

Nineteen years ago, when I lost my sense of smell, my ability to relish those simple pleasures went away. I never thought that at 37 years old, my olfactory nerve would be stolen by a benign brain tumor the size of a tennis ball.

Even when my neurosurgeon told me that losing my ability to smell was one of the side effects of brain surgery, the reality of what that meant didn’t sink in. How could it? After all, I was facing life or death.

Before the tumor — and the surgery that saved, but forever changed — my life, I was a smell-centered person. Smells resonated with me. They had the ability to set my mood or even shape my attitude about ordinary, everyday activities. A soak in that aromatic bath soothed me at the end of a long day.

A sip of orange, cinnamon-flavored tea calmed me in the evening. The sensuous waft of the lavender growing in my front yard delighted me as I rocked back and forth on the porch. I appreciated the world so much more, in part through my nostrils.

At first, I thought I had survived the surgery with my sense of smell intact. I even complained to a nurse that my ICU room stank. Phantom odors, I guess.

I returned home from the hospital in October 1999 after five-and-a-half hours of surgery. I tried to recover and return to my old routine while also adjusting to the loss of sight in my right eye. It took me awhile to understand why my pot roasts burned to a crisp in the oven. I had always used the aroma floating through the house as a sign the roast was close to done. Sometimes my mother would visit to find a banana or some other fruit rotting on the countertop that I had forgotten about.

I didn’t truly realize I couldn’t smell until I received two gift baskets that included scented candles, a fragrant bubble bath and soap. As I sat in a chair, a friend commented on the wonderful aroma of one of the candles. She said it smelled like an autumn day. I inhaled to find no scent of anything under my nose. Nothing.

I ran into the kitchen and opened a bottle of Lysol. Nothing.

I ran outside and snipped a piece of rosemary. Nothing.

I was crushed as the realization of what this meant pressed upon me like the weight of a barbell.

At first, I hid the gift baskets in a closet. I couldn’t bear to see them and risk being reminded of what I was missing. I shoved them behind the door and tried not to think about them.

Months later, when my scalp began to heal from the trauma and incisions of surgery, I realized I couldn’t even get my typical natural high from the hints of coconut and honey in my freshly-washed hair. Shampooing my hair had always been a reassuring, sensory delight. Somehow, it just made me feel better. My aunt would often say she knew when I was at my mother’s house visiting because she could smell my shampoo in the air. Now, that was gone too.

After all that had happened to me, I couldn’t even sniff my way through recovery. It was hard knowing I couldn’t smell my own body. I was changed. It was devastating but I knew I had to find ways to cope with the loss.

It took time, but eventually, I finally mustered the courage to retrieve the contents of those gift baskets. I needed the closet space, but also I was determined not to let perfectly good lavender-scented body wash go to waste. Even if I couldn’t enjoy the benefits of their aroma, I still wanted to use them. I am a practical soul at heart.

I started to remember how much I loved it when people commented on how nice I smelled, whether it was from a scented soap layered with a matching lotion or a tiny dab of White Linen perfume behind my ear. The kind words from others about my personal fragrance became the ultimate compliment. I liked that family, friends and colleagues appreciated that about me even though the same experience was unfortunately lost to me. And so, I happily put the gift scents and soaps to good use as they were originally intended.

The hardest part of moving about the world without a sense of smell is explaining my loss to people. It just doesn’t seem to register to most that such a condition may even exist. In the course of any given week, some unsuspecting person may say: “Smell this. Ooh, that smells good, doesn’t it?” The same people are pretty shocked when I reveal that scent does not register with me. Yes, it is a little awkward. However, my loss of smell has actually forced me to relish and rely on my remaining senses.

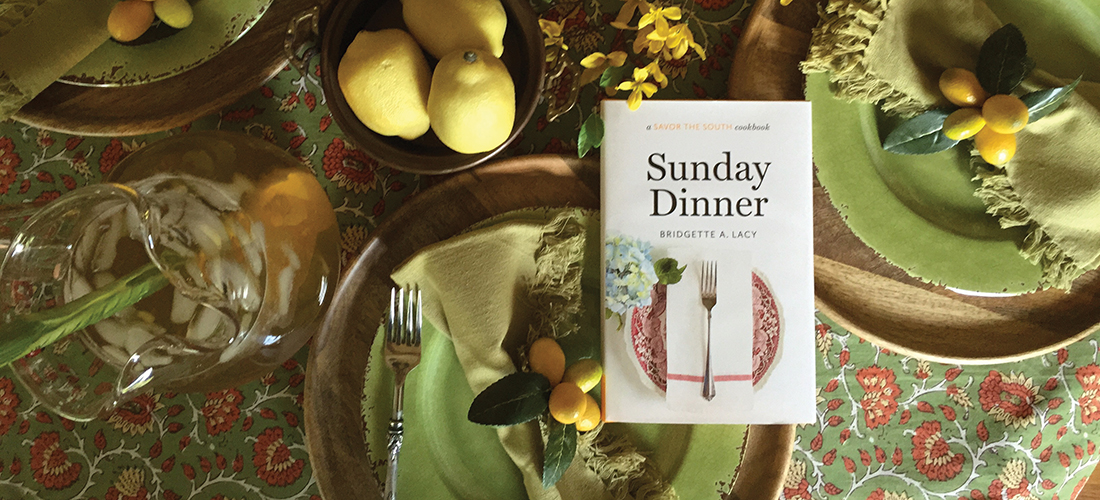

I cherish the fact that I can still taste. Bitter, sweet, salt and tart still delight my tongue. My love of good food and my affinity for sharing it with others inspired me to write my first cookbook. Sunday Dinner, a Savor the South Cookbook from UNC Press, published in September 2015, was a triumph for me. It’s been very well-received. (Editor’s note: It was a finalist for the Pat Conroy Cookbook Prize awarded by the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance.)

I set out to make Sunday Dinner a life-affirming celebration of recipes, as well as a tribute to the value of meals shared and prepared with those you love. It highlights some of my most endearing memories, many of them intricately and lovingly tied to smells and thoughts of home.

The recipes call to mind my time spent in the garden and kitchen with my maternal grandparents. When I was young, I spent many a Sunday afternoon taking in the familiar smell and sizzle of Grandma frying chicken and the sight of Papa’s Nilla Wafer-brown pound cake cooling on the back porch. His cakes always released their own distinct, irresistible aroma that filled the air.

When I’m standing in my own kitchen recreating these time-honored dishes I grew up with, I sometimes think about my sense of smell, or rather the lack of it. As quickly as those thoughts appear, I redirect them to focus on the loved ones who originally created these meals and how much my family continues to influence me in and out of the kitchen.

As the years have passed, every once in a while, I experience a smell memory. It’s a curious thing. Once, in a grocery store, while walking past a display of country ham in sealed vacuum packs, I remembered the smell of country ham frying in a pan. It was so real I could practically taste it. Another time, driving home from a day spent with a male friend and his mother, I suddenly felt like I could smell spring in the air. The car windows were down and I remembered how the scents of that season came rushing in with the crisp smell of freshly-cut grass combined with the sweetness of one of my Tropicana, long-stemmed roses. These smell memories come flooding back with such crystal clarity, I almost feel like I really did smell something.

When that happens, I’m not mad. I’m not upset. I just remind myself that while that part of me is gone, so much more remains. Then, I simply and resolutely smile, take a very deep breath and thank God.

Come íní Get It!

The following dishes are one of many evocative of home and family:

Mamaís Meaty

Crab Cakes

I request my mother’s crab cakes almost every time I return to my childhood home. These meaty crab cakes flavored with Old Bay Seasoning are far better than any I’ve had at a restaurant. They are crunchy on the outside from the cornmeal and moist on the inside. My mother serves them on Martin’s potato rolls with potato salad. There will be no leftovers with these. In fact, get to the table fast. These won’t last.

Makes 8 servings

1 pound fresh jumbo lump or lump crabmeat

1 celery stalk, finely chopped

1⁄2 medium white onion, finely chopped

1⁄2 green bell pepper, finely chopped

2 tablespoons Hellmann’s mayonnaise

1 teaspoon Old Bay Seasoning, or more, to taste

1⁄3 cup Italian-seasoned bread crumbs

Cornmeal for dredging

2 cups vegetable oil (more or less, depending on the size of your skillet)

Place the crabmeat in a large bowl. Remove the cartilage (lump crabmeat doesn’t have much). Add the celery, onion, green pepper, mayonnaise, Old Bay, and bread crumbs and stir together gently with your hands so as not to break up the crab too much. Add more mayonnaise if the mixture looks too dry.

Shape the mixture into eight patties about the size of the palm of your hand. If you are cooking the crab cakes immediately, dredge them in the cornmeal. If not, you can store the crabmeat mixture in a covered container in the refrigerator until ready to cook (up to 2 hours) and dredge them just before cooking.

Heat the oil in a large skillet over medium-high heat until it shimmers. Don’t use too much oil; it should reach only halfway up the side of the crab cakes. Gently place the crab cakes in the pan and fry on one side until browned, about 2–3 minutes. Carefully flip over the crab cakes and fry them on the other side until they are golden brown. Drain the cakes on a paper towel and transfer them to a warm platter. Serve with your preferred sauce.

NOTE * Buy the crabmeat the day of or the day before cooking because fresh crabmeat perishes quickly. Jumbo lump or lump crabmeat makes for the best crab cakes. The meat is pricey, but it’s worth it for this special meal.

Estherís Summer

Potato Salad

My mother started making potato salad when she was a girl. The oldest of four children, she made it Sunday after church and would make enough to fill the large vegetable compartment at the bottom of the refrigerator. Her father, my beloved Papa, a blue-collar worker, often carried the potato salad in a mayonnaise jar for his lunch. My mother was a Moore, and many Moore family gatherings were marked by this classic summer salad. “My love of potato salad came from watching my aunt Shirley make it and smelling it in my grandmother’s kitchen,” she says. The scent of fresh-cut celery, onions and pickles drew her closer to the bowl. “We always ate it when it wasn’t ice cold. That’s why I like it today when it’s just made.”

Makes 6-8 servings

6 medium white potatoes

1 cup chopped celery

1 white onion, chopped

1⁄2 cup pimentos

5–6 sweet pickles, chopped

3 hard-boiled eggs, grated

5 tablespoons Hellman’s mayonnaise

2 teaspoons prepared yellow mustard

2 teaspoons cider vinegar

1 teaspoon sugar

Salt and black pepper, to taste

Paprika for garnish

Wash and peel the potatoes and cut them in small, uniform chunks. Put the potatoes in a pot and cover them with water. Boil until fork-tender, about 20–25 minutes. Drain the potatoes in a colander and let cool, about 30 minutes or so. You want them warm but not hot.

Transfer the potatoes to a large bowl and add the celery, onions, pimentos and pickles.

In a separate bowl, combine the grated eggs, mayonnaise, mustard, vinegar, and sugar. Taste it. Adjust the seasonings to your taste.

Gently combine this mixture with the potato salad. Season with salt and pepper. Sprinkle with paprika and serve. OH

Recipes from SUNDAY DINNER: a Savor the South Cookbook by Bridgette A. Lacy. Copyright © 2015 by Bridgette A. Lacy. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org

Bridgette A. Lacy served as a longtime features and food writer for The News & Observer in Raleigh. She is also a contributor to The Carolina Table: North Carolina Writers on Food.