The Lost Colony

America’s oldest mystery gets a new look, a new life and a new vision

By Gary Pearce • Photographs by Joshua Steadman

A drive that takes 30 minutes to an hour from the Outer Banks takes you back 434 years.

Back to America’s beginnings. Back to the earliest English settlers. Back to America’s oldest mystery: The Lost Colony.

You start the drive on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. You leave behind the beaches, the bars, the shops, the restaurants, the crowds and the traffic.

Cross over the causeway to Roanoke Island. Pass through the town of Manteo. Turn off the main road into the dark woods along the sound. Park and walk through the trees. It’s evening, nearly sunset. In the quiet, you hear only the wind and the water.

You’re standing where, in 1587, a band of English colonists abandoned a tenuous settlement they’d established less than a year before. They set off in search of a new home. And they disappeared.

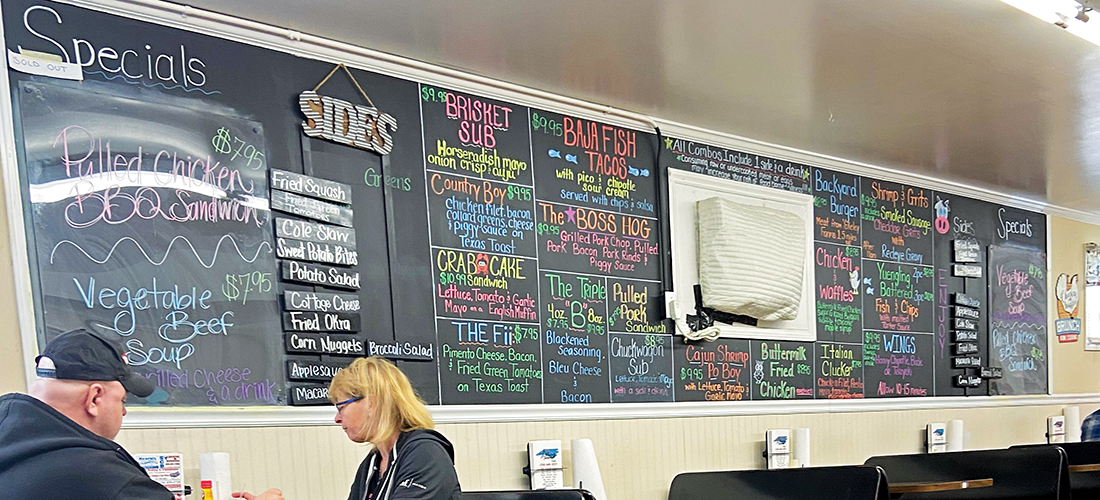

You sit in an open-air theater where, on summer nights since 1937, the colonists’ story — and the mystery of their fate — have been brought to life by The Lost Colony, America’s oldest outdoor symphonic drama.

Last summer, COVID cancelled the production for the first time since World War II.

This summer, The Lost Colony is back — with new energy, new casting, new production techniques, a new script and musical score, and a new look at what might have happened when two cultures, English and Native American, came into contact and conflict.

This will be the 84th summer the drama is performed in Waterside Theatre, at the northern edge of Roanoke Island in Dare County. The theater is part of the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, which preserves the location of Roanoke Colony. The colony was the first English settlement in the New World and the birthplace of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America.

The play itself is a historic dramatization. It began as a federally funded Depression-era project. The theater was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The Lost Colony was intended to be a one-year production. Then President Franklin D. Roosevelt attended the show with a good deal of media fanfare on August 18, 1937 — the 350th anniversary of Virginia Dare’s birth and a little more than a month after the July 4th premiere.

After FDR’s visit, the crowds came. The show was so popular that organizers decided to stage it every summer. They’ve been doing it for 83 years. World War II forced a four-year cancellation.

Last season’s cancellation in the pandemic was a financial blow to the Roanoke Island Historical Association, which produces the drama. The year-round staff had to be greatly reduced.

But Kevin Bradley, the association’s board chair, says, “The year off turned out to be a blessing. We had the time to reimagine the production, recharge our batteries and refresh how we tell this story.”

A new director/choreographer was recruited: Jeff Whiting, whose Broadway credits include Bullets Over Broadway (6 Tony Nominations), Big Fish, The Scottsboro Boys (12 Tony Nominations), Hair (Tony winner for Best Revival) and Wicked 5th Anniversary.

The New York Times called Whiting a “director with a joyous touch.”

Whiting says his goal is “to honor the history of what occurred here on Roanoke Island, and to honor the legacy of this important theatrical work. As the wind rolls off Roanoke Sound, it whispers the tale. It’s my job as director to listen to that breeze and bring to life what happened here so many years ago.”

Whiting has reduced the lengthy original script, written by North Carolina playwright Paul Green, allowing the scenes and story to move faster and providing more time for theatrical storytelling.

Additional theatrical devices will support the storytelling, including large-scale puppets, a military-style drum corps and a new symphonic score. The show will also feature traditional dances from both Native American and English historical cultures.

But Paul Green’s imprint remains.

Green was a Harnett County farm boy who became a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright. Green was the father of “symphonic drama.” He saw it as the people’s theater, a way of telling Americans about their past.

Green had a deep concern about race relations. His vision of The Lost Colony reflects what can happen when different cultures and races come together.

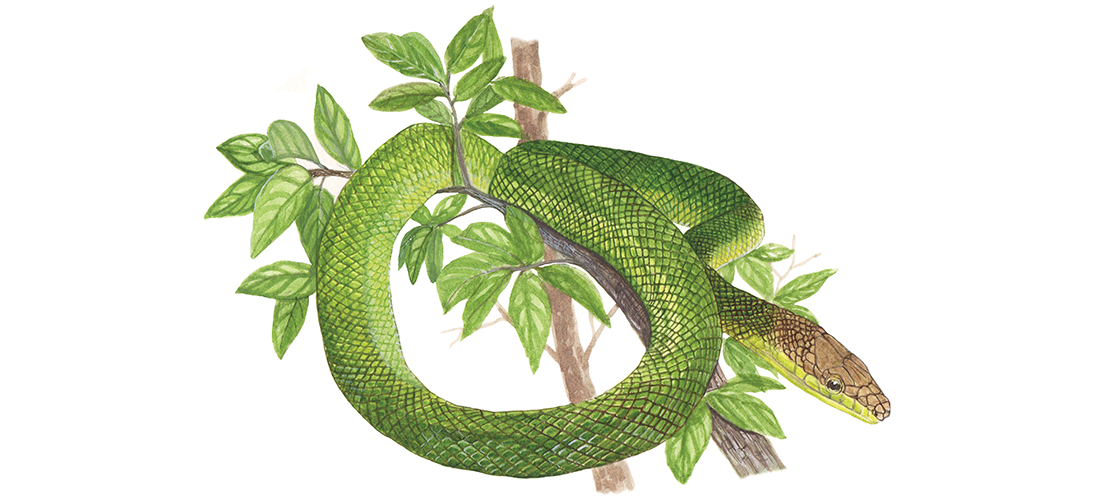

In the past, the production didn’t always use Indigenous actors to portray the Native American roles in the play. Seeking authenticity, the association reached out to Chairman Harvey Godwin Jr. of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. He now serves on the board of directors.

With the tribe’s help, Native Americans were recruited as actors and dancers. Auditions were held in Robeson County, in the Lumbee tribal territory.

“We are appreciative of the Historical Association’s desire for accurate and historical representation,” Godwin says. “With North Carolina’s American Indian population numbering more than 100,000, it enriches the production to see and hear their voices on stage.”

Kaya Littleturtle, the Lumbee Tribe Cultural Enrichment Coordinator agrees, adding that the new choreography, regalia, language accuracy and orchestration help to insert “more of an authentic and cultural American Indian perspective into the play.”

But the real test is whether the new production will bring back audiences, says John Ancona, general manager: “We want to give our audience an exceptional evening’s experience in an outdoor setting — an experience you can’t get many places. We want to inspire interest in a part of history that remains a mystery today.”

Ancona hopes that visitors will leave the theater intrigued by the story. Perhaps they’ll dip into the ongoing, unending research and archeological exploration that still seek clues about The Lost Colony.

Where did they go? What happened to them? Did they drown at sea? Were they killed by natives, or by Spanish raiders? Or did they quietly go live with a friendly tribe?

We don’t know. But we do know the colonists dreamed of freedom. They dared a dangerous ocean voyage. They sought a new life in a new land.

Take the drive back to their world. Walk where they walked. See and feel what they saw and felt.

Hear their story. Listen to the wind, the water and the trees. Feel the mystery of The Lost Colony.

The Lost Colony’s 2021 season launched May 28 and continues through August 21. For tickets and more information: thelostcolony.org OH

Gary Pearce is a member of the board of directors of the Roanoke Island Historical Association. He and his wife, Gwyn, divide their time between Raleigh and Nags Head.