Wandering Billy

Wandering Billy

The Organ Pipes Are Calling

Nothing could be fina than to play the Carolina

By Billy Ingram

“Movies are a fad. Audiences really want to see live actors on a stage.” — Charlie Chaplin

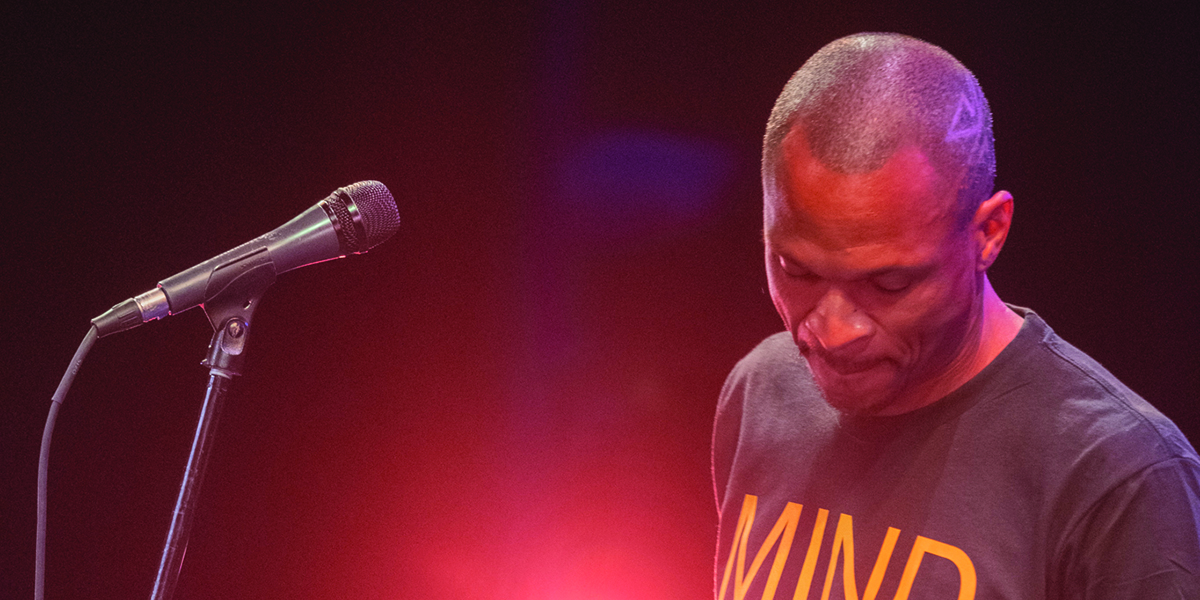

The Carolina Theatre will once again be giving us the silent treatment at 7 p.m., April 30, when Mark Andersen — one eye focused on the screen — performs his original score for Charlie Chaplin’s highly acclaimed, bathtub-gin-era rom-com, The Circus. First projected on the Carolina’s big screen in March 1928, this was the last motion picture Chaplin made during the pre-talkie era, winning the Little Tramp his first Academy Award for “versatility and genius in writing, acting, directing and producing.”

Rapidly approaching its 100th anniversary, the Grecian-Revival-inspired Carolina Theatre boasts an unusual but valuable component installed before opening night: a Robert Morton Pipe Organ designed and constructed specifically to accompany silent pictures. It’s become a rarity; mere months before this opulent movie palace (locally designed by James M. Workman) first welcomed moviegoers in 1927, sound had arrived for motion pictures, leading to the company that made those instruments going belly-up in 1931. As a result, the Carolina Theatre possesses the only remaining Robert Morton Pipe Organ in North Carolina.

This magnificent wind-and-keyboard instrument is in pristine condition, thanks to Mac Abernethy, who, beginning back in 1968, assembled a team of volunteers determined to restore this long-neglected music maker to its full-throated glory — while, at the same time, city leaders were finalizing plans to raze the Carolina Theatre in favor of a municipal parking lot. “It’s taken a lot of work with a lot of help over the years,” Abernethy says of maintaining that Art Deco-inspired, three-manual console pipe organ. “In 1968, we had to come here after the last movie at 11 o’clock to do any work. We’d be up here until 2, 3, 4 in the morning.” The area around the theater in those days was a veritable urban hellscape. “When we went to leave, you didn’t know what you were going to run into.”

For last February’s screening of a rarely seen silent race film, Body and Soul, which was produced, written and directed by Oscar Micheaux, the Carolina Theatre invited world-renowned composer and musician Mark Andersen to provide accompaniment. “You name it, I’ve played it,” Andersen says of the illustrious pipe organs he’s performed with across the globe. “Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall in London. I was associate organist at Notre Dame in Paris and went to school at the Paris Conservatory there.” Having played over 400 concerts across America on just about every large organ that exists, Andersen served as organist for the Boston Symphony and Boston Pops under Arthur Fiedler and as head staff music arranger for NBC in New York.

Andersen’s love for pipe organs began in first grade, when he won the North Carolina State Piano Teacher’s competition. “I’m the youngest artist that has ever played with the North Carolina Symphony,” he notes. At that time, the church he was attending was installing a brand-new pipe organ. “The company that put that organ in was kind of amazed that this little guy was interested in learning to play it.” Having grown up in Lumberton, Andersen recalls that “the first time I played [the Carolina Theatre’s] organ I was 8 years old. I was with a group of musicians that were coming here because we could not imagine a pipe organ in a movie theater. I met Paul Abernethy, who was Mac’s dad, and he showed us the organ that sat down in the orchestra pit then.”

Sixty years later, bringing an added excitement and authenticity to its Silent Series, Mark Andersen returns to the Carolina.

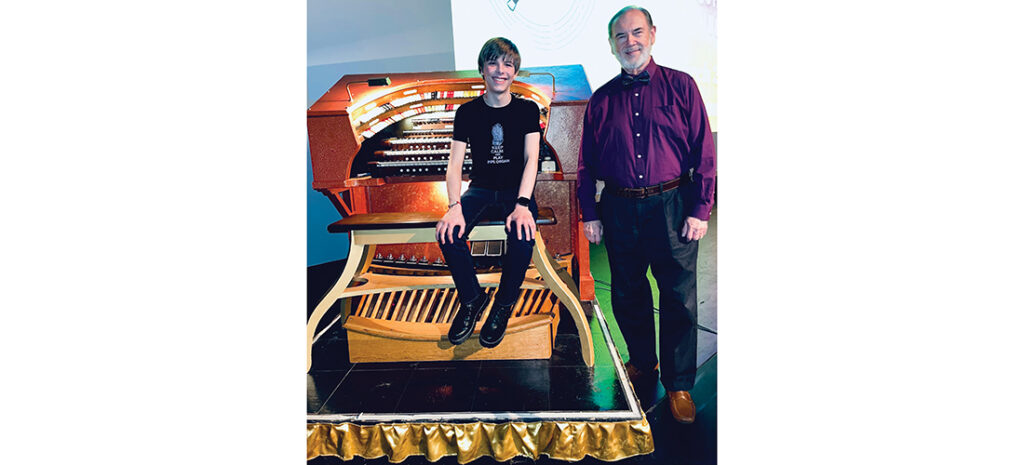

I got to roll my grapes over that Robert Morton Pipe Organ when I was introduced to the maestro recently. Also in attendance was musical theater star Brody Bett. He, too, had an organic epiphany at a very young age. “I’m homeschooled,” the 14-year-old triple-threat performer tells me. He recalls going on a field trip with fellow homeschooled students to Greensboro’s Christ United Methodist Church. “I saw this ginormous pipe organ. I was like, wow, you have all these sounds and it’s so massive and it’s so powerful. My 5-year-old mind, seeing that organ, I’m like, ‘Dude, I think this is what I’m going to do for the rest of my life!’”

If the name Brody Bett sounds familiar, I hipped you to his amazing career in my January 2023 column. He was 6 years old when he first got up on the boards in Greensboro theatrical productions. Then, at 8 years old, he landed the juvenile lead in the multimillion-dollar Broadway touring production of Finding Neverland and spent the next season crisscrossing the country as Charlie in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Off-ramped due to the pandemic, the lad’s career undertook an unexpected but welcome pivot when he began securing roles as a voice-over artist for animated shows on Nickelodeon, Netflix and Amazon Prime. Currently, he can be heard as Rocky in the PAW Patrol: Grand Prix video game and Kakeru in episode 4 of the hit anime series Kotaro Lives Alone.

Brody remembers like it was yesterday (I mean, it practically was) when he sang and danced across the stage with the Community Theatre of Greensboro at the Carolina. “The first silent movie I ever saw here was when I was 9 years old,” Brody says. “Michael Britt, who unfortunately passed away last year, accompanied The Phantom of the Opera.”

All of the scores that accompany the silent films Andersen performs were written by him. But still, he says, “You have to closely watch the movie while you’re playing.” He remarks that, when composing a soundtrack for silents, it’s just like scoring a live movement. “Like the soundtrack of a talkie movie, it’s meant to be played at a certain time. Is the projectionist running it too fast, running too slow, where your scenes change, and so forth?”

Brody has sent fingers flying across the keys in an impressive number of venues. “I’ve played the Wanamaker Grand Court Organ in Philadelphia,” the largest, fully-functioning pipe organ in the world, he says. “I’ve played the Bedient Organ at First Congregational Church in Sioux Falls and the Walt Disney Concert Hall Organ in LA, the one Manuel Rosales designed.” He can list so many others, including arguably the most famous such instrument in America, the Salt Lake City Tabernacle (formerly Mormon Tabernacle) Organ, festooned with over 11,000 harmonic pipes.

Closer to home, he says, “I’ve been playing for church Sundays at Irving Park United Methodist — it’s a great space.” Brody Bett’s first funky single, “Times Square,” can be found on Spotify and sampled on YouTube.

I wonder if one day I’ll be attending a silent at the Carolina and Brody will be in front of the keyboard. OH

Born and raised in Greensboro, for a 10-year period in the 1980s and ’90s, Billy Ingram was part of the Hollywood design team the ad world enshrined as “The New York Yankees of motion picture advertising.”