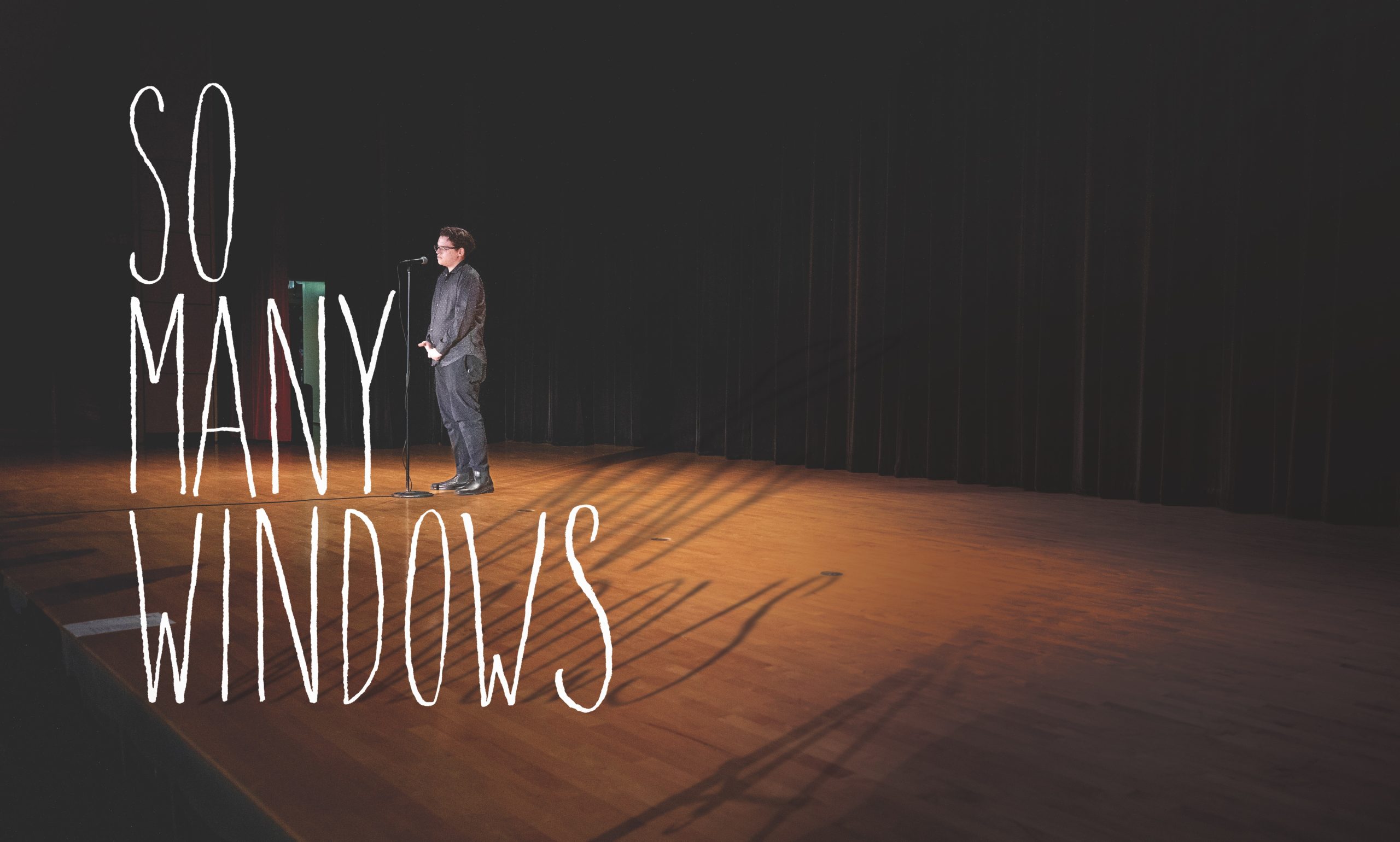

Going to Seed

GOING TO SEED

Going to Seed

A family strives to protect a way of life in Julian

The first thing you’ll likely notice when you pull up to the rambling, wood-and-corrugated facade of the Julian Milling Company on Old 2nd Street is the cats.

They’re parti-colored and striped, light-colored and dark. They’re napping under a tree, they’re lolling on the loading dock — some perched primly on upturned buckets. There’s even a cat peering down from high up in the rafters.

Here’s the irony.

I’ve driven out to rural Julian to speak with Eric Horney, purveyor of the mill’s most popular product these days — Beardo’s Birdseed.

A little history.

The Julian Milling Company is a landmark. It’s been around since 1895, first milling flour and, later, cornmeal. The first machines were powered by steam — the facility converted to electricity with mills to grind livestock feed in the 1940s. Generations of Guilford and Randolph county farmers have hauled grain — hundreds of thousands of tons — to this very spot, where it has been ground into feed for horses, cattle, swine and poultry.

I can’t tell you how many feline generations have protected the mill, but I can tell you that the Horney family has been involved with the business for three.

Eric’s grandfather, J. Davis Horney, who began working at the mill in 1935, purchased the operation a decade later and was joined by his son James Davis Jr. — nicknamed Jimmy. The two of them worked together, growing the production of the mill, for more than 50 years.

Jimmy, Eric’s father, who is now 83 years old, emerges from back in the mill as Eric gently encourages a couple of cats to make room for me to step up onto the dock.

We shake hands and they invite me to sit a spell.

Jimmy and Eric are big, genial, country men. Jimmy is clean-shaven, but Eric, who is 53 years old, sports a thick beard that would be the envy of any Civil War general you can think of.

These men have seen many changes in agriculture over the years.

Growing up, Eric split his time between Greensboro and Julian after his parents divorced.

“I went to Page High School,” Eric says. “But on weekends, I’d come out to Julian to work with my dad and granddad.”

After graduating from Lees-McRae College with a degree in business administration, Eric returned to work at the mill in Julian.

The period of the 1960s through the 1990s was a prosperous time for Julian Milling Company. The business had not only its milling operation, but also a garden center. People could walk around and buy plants and shrubs while their grain was being milled.

Many of its biggest feed customers were dairy farms.

The mill owned and operated two trucks, each with a capacity of eight tons. Some of the dairies were so large that they received a truckload of feed each day.

“We’d mill the grain, add ingredients like protein, molasses and minerals, and haul it out to a farm,” Eric says.

In 1997, the year his grandfather died, Eric worked full time at the mill, along with two other full-time employees.

But many of the dairy farms were shutting down. And Eric noticed another change.

Saturdays were always the busiest day for grinding livestock feed. When the mill opened at 7 a.m., there would already be a long line of trucks and pickups outside loaded with grain, waiting.

“So one day, I said to my Dad, ‘Now wait, all these people here on a Saturday morning, what do they do all week?’”

Jimmy nods, remembering the conversation.

“And I said, ‘Well, they have full-time jobs,’” Eric continues. “‘They aren’t farmers, they’re weekend farmers.’”

Over time, even the ranks of the part-time farmers diminished.

“The children of the weekend farmers, they didn’t usually go into farming,” Eric says. “They’d take a job, sell the land off to developers.”

We pause for a moment, watching as a Mustang convertible pulls up in front of the mill.

“That’s my brother, Neil,” Eric says.

A couple of the cats move over to the shade of Neil’s car as he makes his way up the steps to the dock.

“Neil’s a full-time pilot for NetJet,” Eric says. “He comes in on his days off and helps out.”

“We’re all part-timers,” Jimmy laughs.

“Yeah, I got my licenses to sell health and life insurance last summer,” Eric says. “But I haven’t sold any policies. I keep hanging onto a dream.”

The dream is to earn a living with his work at the mill.

Yes, for decades the old mill has survived trying times — but maybe the biggest challenge yet lies just half a mile down the road.

The new Toyota Battery Manufacturing Plant.

To see it emerge from the trees and fields while you’re driving in this rural area is surreal.

A campus of 2,200 acres. A capital investment of $13.9 billion. Employment for 5,000 souls. Building restrictions on nearby properties because of the accident risks in lithium battery manufacturing.

“It’s changed the whole world around here,” Jimmy says, shaking his head. “It’s crippled our walk-in traffic.”

“Anybody who lives close by has a ‘for sale’ sign in front of their house,” Neil adds.

Eric nods his head.

“The future is online,” he says. “If no one ever walks through the front door of the mill again, we can still make it.”

Eric has a strategy.

At the Julian Milling Company location, you’ll still find packets of vegetable and flower seeds, hand implements, fertilizers and weed killers — some on the shelves for so long that they’re practically relics. There are also bags of “sweet feed” for goats, cows and horses, chicken feed for laying hens, “scratch” (a mixture of grains and seeds) for chickens, pigeon feed and birdseed.

Eric has focused on his bestselling birdseed for the past couple of years, marketing it online through Etsy and Amazon along with placing it with selected retailers and farmers markets.

“We’ve already shipped our birdseed to all 50 states, Guam and Puerto Rico,” Eric says.

During this time, he’s concentrated on finding local, high-quality suppliers of his ingredients to enhance the freshness of his product. Plus, the mill is a participant in the Got To Be NC initiative with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services.

And Eric has just launched an online platform selling — remember the beard I told you about? — Beardo’s Birdseed.

Eric takes me back to the oldest part of the building, where one of the electric mills is located. This is the machine he uses to mix the ingredients for Beardo’s Birdseed.

“There’s not a blade inside cutting anything — there’s an auger,” he says. “It’s funnel-shaped, gravity-fed, so it just mixes the ingredients over and over.”

“This is basically just like the mixer on the kitchen counter in your house,” Eric says. “But this one holds a thousand pounds.”

He points out the grill opening on the floor where he pours the various grains and seeds into the mill. Once mixed, the birdseed is bagged right on the spot.

Beardo’s is available online by individual order or by subscription and can also be purchased by nonprofits for fundraising purposes.

Dusk is approaching, so Eric takes me back out onto the loading dock, where I say my goodbyes to Jimmy and Neil. Some of the cats stand and take a stretch.

Eric looks up in the rafters.

“Ellie,” he says, “get on down here.”

The cat makes her way gracefully to the dock.

Eric tells me that the rafters are Ellie’s favorite spot. To his knowledge, she’s the eldest of the cats at age 12.

“Someday, she’s going to doze off up there and fall and hurt herself,” he mutters.

All the cats, of course, are just doing their jobs, protecting the mill — as they’ve done for generations.

And that’s something the old mill needs right now.

I think the birds will understand.