Home to Port

HOME TO PORT

Home to Port

A roving designer settles in High Point’s Emerywood

By Cassie Bustamante

Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

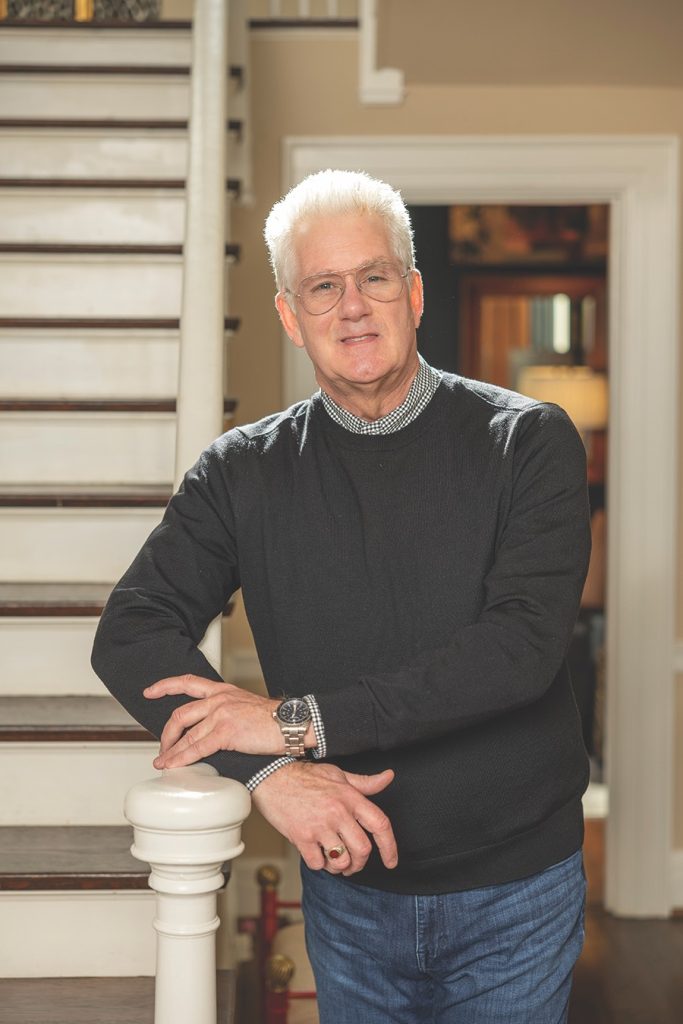

“How many times can one decorate and move?” asks Mark Abrams, co-owner of PORT 68, a home decor company based out of Chicago. He’s lived all over the States in his 62 years. As a young man in the mid-1980s, Abrams first visited the Furniture Capital of the World and had a sense of knowing he was going to one day call it home; friends told him he was insane. But he’s got the last laugh because “fast forward and here I am!” And, it turns out, his century-old Colonial in High Point’s historic Emerywood is the house this wandering spirit has lived in the longest. Perhaps this time he’ll pull his ship into harbor for good.

Born and raised in Demopolis, Ala., Abrams remained in the Yellowhammer State during college, initially planning to study architecture. “I realized real quick there’s a huge amount of math requirements,” he quips while petting his black-and-white cat, Freddie, perched in his lap. Instead, he graduated from the University of Alabama in 1985 with a degree in communication. At the time, the school didn’t allow double majors, so Abrams minored in fashion merchandising and design, considering a career as a retail buyer.

But, during his junior year of college, an internship with one of the largest design-marketing companies, Gear-Holdings, in New York City, shifted his trajectory. “Gear,” as Abrams refers to it, was co-founded and owned by a family friend, the late Raymond Waites, who also hailed from Demopolis. “I went to New York and it changed my life,” muses Abrams.

“It was like a big grad school,” he says, where he learned the ropes of both business and design as a Gear employee, eventually stepping into the role of visual director. “Because of Gear, and who I knew and what I was doing,” says Abrams, “I was published in every shelter magazine there was and on a few covers of books for my design work.” One of his first projects was a four-part publishing series with Better Homes & Gardens that wound up in a book. His work at Gear is what introduced him to High Point, where he set up a showroom for one of the company’s licensees.

Eventually, Abrams grew tired of grinding his gears. “I just worked and worked and worked and made no money.” What his bank account lacked in abundance, he made up for in a padded portfolio. Plus, Waites had introduced him to “the who’s who of the industry,” providing him with valuable connections. After a few years, he left Gear and jetted to Los Angeles, where new adventure awaited.

And ever since, he’s barely kept his feet in one spot for more than two years at a time. “I’ve moved 12 times cross-country,” he says. “I’ve lived in, let’s see, New York, L.A., Dallas, St. Louis, Kansas City, Greensboro — twice — New York again.” Plus, he adds, Ferndale, Washington, and, before High Point, Chicago.

In 2009, with industry veteran Michael Yip, Abrams co-founded PORT 68. Its mission? “Bringing home beautifully designed products from ports around the world to you.”

At the time, Abrams was living in Greensboro on Kemp Road. Before that, he’d been living just around the corner on Watauga in Hamilton Forest when a realtor knocked on his door and told him someone wanted to buy his house. Abrams, a sucker for flipping houses recalls, “I said, ‘As long as you can find me one in this neighborhood, that’s fine.’ And he did!”

But with the start of the company, Abrams relocated to Chicago, where PORT 68 has its headquarters. With showrooms in High Point, Atlanta and Dallas, the company decided to look for what Abrams calls a High Point “market house,” a place where the team could stay when they needed to be in the city. He called his pal, real estate agent Lee Kemp, and asked her to show him a house he had his eye on. Turns out, “it was way too much work.”

“I was just adding it up in my head and I am going no, no no.” But Kemp came through with another house that was being sold as an estate and was a stone’s throw away from the one he’d already seen. Abrams did a 15-minute walk through, made an offer he didn’t think they’d ever accept and hustled off to the airport.

As soon as he landed at O’Hare Airport, he got the call that the offer had been accepted. “I was like, ‘What!’” he recalls.

While he hadn’t planned on moving, after nine years of living in the Windy City, where “the snow would blow horizontally,” this warm-weather-loving Southerner had had enough. Abrams traveled often for work and was spending at least eight weeks a year in High Point as it was, and being in High Point would also put him within driving distance to the Atlanta showroom. Why not just move there?

After all, he says, High Point has a “very tight-knit design community” that you won’t find anywhere else, the sort of place where a close-knit group of industry friends can get together to “complain, discuss, egg each other on — all the things you need to talk about.”

During Market, the PORT 68 team infiltrates and makes his house their home base. “I call it the sorority house because people are all over the place and it’s kind of a wreck.” But, he adds, he always wants his guests to feel right at home. “My house is where you can put your drink anywhere and don’t worry about it, put your feet up anywhere and have a good time. I don’t live in fine antiques; I live in old things that I love and that’s kind of it.”

Of course, being in High Point also made it a little easier to get back to his hometown of Demopolis, where his aging parents still lived. About the time Abrams landed in High Point, his father had just begun battling Alzheimer’s. With his parents’ failing health, Abrams found himself traveling to Alabama every two to three weeks. Assuming the time would come, Abrams prepared his home for his mother to move in, readying the main-floor bedroom and handicap en-suite bathroom the previous owner added.

Sadly, he says, “That didn’t happen.” In 2022, his mother passed away, followed by his father in March of last year.

The bedding in that main-floor guest space was assembled originally with his mother in mind. A black-and-white duvet and bed pillows juxtaposed with playful, burnt-orange tiger “hide” throw pillows feature a “timeless” toile that was created by Gear in 1986. Fellow Demopolitan Waites wanted to craft the classic pattern with a hometown-homage twist. Using antique document fabric, Abrams says, they added “vine-and-olive people,” an homage to the French expatriates who founded Demopolis. For Abrams, the most exciting element is that the plantation-style house depicted on the toile fabric is historic Bluff Hall, which had been owned by Abrams’ grandfather before he sold it to the Marengo County Historical Society.

But the real kicker? “My mother turned down living in the house [Bluff Hall] because, she said, ‘I don’t want to live in an old barn,’” says Abrams with a chuckle. Judging by the toile design, Bluff Hall is far from being considered a barn.

These days, Abrams doesn’t travel back to Demopolis as much now that both parents are gone. “The estate is coming to an end so I feel a slight relief of just the physical driving back and forth.”

Making his house a home while running a business and taking care of his long-distance parents eventually took its toll on Abrams. In June 2024, he went into atrial fibrillation, abnormal rhythm of the heart, accruing the equivalent of “a weekend at the Ritz Carlton,” referring to his hospital bill. But, he says, “I am alive.” The cost was well worth it because “little High Point Hospital” was able to regulate his heart rhythm. And now, he says, it’s time for him to make himself a priority.

Abrams kept a few sentimental family pieces that he’s seamlessly blended into his design, such as a wooden box he’d given his father 30 years ago that now sits on the sofa table. While he describes his style as somewhat “eclectic” — a mix of tonal colors and metallics, texture, layers, and animal prints — he also says, “I am very calculating when designing.”

The living room, off of which sits a covered porch, is the prime example of his design ethos at play. A rich, streamlined velvet sofa faces two lush, armless chairs. A woven, natural rug anchors the space, layered with a smaller, vintage-style rug in the warm earth tones that reverberate throughout the home. In front of his windows, two white, carved-wood screens he found years ago at a Chicago antique shop — for an absolute steal — provide privacy.

Abrams has filled built-ins — stylishly and meaningfully — with books, decorative pieces and souvenirs, and, of course, PORT 68 mirrors. In front of one, three glass boxes display sentimental collections from his many travels to Vietnam, India, England and all across the globe. And, to top it off, a silver engraved vessel, “my baby cup.”

On the narrow strip of wall next to the built-ins Abrams points out a set of three steel, engraved bookplates found in Palio, Italy. “They’re all my initials.”

In the adjacent sitting room, a large, bright-orange Suzani tapestry picked up in Istanbul is stretched on a wooden frame, transforming it into a show-stopping work of art. Textiles are one of Abrams’ favorite souvenirs to purchase when abroad. “They don’t take up any room and they don’t break in your luggage,” he quips.

The Suzani, it turns out, hangs on a wall Abrams had hoped to knock down to create a spacious eat-in kitchen, but that turned out to be structurally impossible. Instead, he made small cosmetic changes, painting the kitchen and updating it with leftover wallpaper from a showroom. The paper, a neutral tan-and-white trellis design, is “Island House” by Madcap Cottage, a local High Point brand that is a PORT 68 licensee, along with iconic New York fabric house Scalamandré Maison and colonial classic Williamsburg.

Just off the kitchen is a 100-year-old original, a dark-wood butler’s pantry with glass-door uppers. Abrams has painted the wall behind it orange, echoing the color of his Suzani. “I wanted to gut this,” Abrams admits, noting that several drawers were not functioning, “but my business partner’s wife freaked out and she goes, ‘Do not take it out!’” His solution? He removed those drawers and added a wine refrigerator, which nestles in perfectly. And now, he appreciates the marriage of display piece and storage the cabinet offers. “I gotta put my mother’s junk somewhere,” he says with a laugh. “All the silver — lots of silver — I call it the burden of Southern silver” — a phrase he stole from Waites’ wife, Nancy, a fellow Southerner.

In the dining room, Abrams once again used wallpaper — a Thibaut metallic rafia in easy-to-remove vinyl — to refresh the space. Throughout the house, the plaster ceilings needed repair so he “wallpapered the ceiling so I didn’t have to deal with the cracks or the plaster.”

In the center of the dining room ceiling, a large-scale, traditional brass chandelier hangs, adorned by simple black shades, which, Abrams jokes, cost more than the fixture itself. “I bought my chandelier — my brass chandelier, which would be thousands of dollars if you bought it through Visual Comfort — 20 bucks at Habitat.”

He frequents the local Habitat for Humanity retail store because vendors regularly abandon showroom pieces there. Pro designer tip? “You just need to go. All. The. Time.”

In his primary bedroom upstairs, another Habitat find covers the entire wall behind his headboard. Unseen to the naked eye, Abrams notes that there are two off-centered windows hidden behind pleats of creamy, linen-wool fabric, a visual trick that allows him symmetry. The whole treatment, he says, cost him just around “100 bucks.”

A study in cool neutrals — black, gray, tan and chrome — his bedroom is a comparatively soothing and minimalistic space. The rug, a tan-and-white plaid “was custom made for me through my friends at Momeni.” In the corner, an easel features a sketch of the human form and, above a black settee, two large astronomical prints mimic the room’s colors.

“This is the contrast,” says Abrams, leading the way to a chocolate-black bedroom one door down. “I always like having one dark bedroom for guests because it’s cozy,” he says. Flanking the windows, black-and-white zebras leap across scarlet Scalamandré drapes.

Abrams gestures to the smaller furnishings in the space. “A lot of this stuff I’ve had forever, from house to house to house, and it just works when you buy classic things,” he says. Metal pedestals purchased 30–40 years ago from Charleston Forge display porcelain urns.

The last “bedroom” of the upstairs is smaller and the staircase to the attic lines the back wall. Abrams, who doesn’t need a fourth bedroom, turned it into his dressing room. The pièce de résistance is the open cabinet displaying what he calls “my trust fund” and perhaps this collector’s most expensive pieces, amassed over time. Again, he reiterates the importance of buying something classic and taking care of it, except this time he’s talking about his extensive shoe collection. “Luckily, your feet sizes don’t change. This may change,” he says as he pats his stomach, “but that doesn’t change.”

For now, Abrams says, the house is “all done over.” He’s repaired, repainted and wallpapered almost every surface. Of course, there’s still an old basketball slab in the backyard that he’s contemplated painting to resemble a pool, complete with a big, inflatable rubber duck. “But,” he says, “I don’t know if anybody would get my humor.”

At home, relaxing on his velvet sofa, Abrams reflects on his life. “All from a boy from a small town in Alabama,” he muses. “It’s been a crazy adventure.”

Is it time to call an end to the crazy adventure and plant permanent roots in High Point?

As if he hadn’t yet thought of it, he says, after a beat, “Well, yeah, maybe.”