O.Henry Ending

Embracing Juno

The tarot reading — and tattoo — that changed my life

By Corrinne Rosquillo

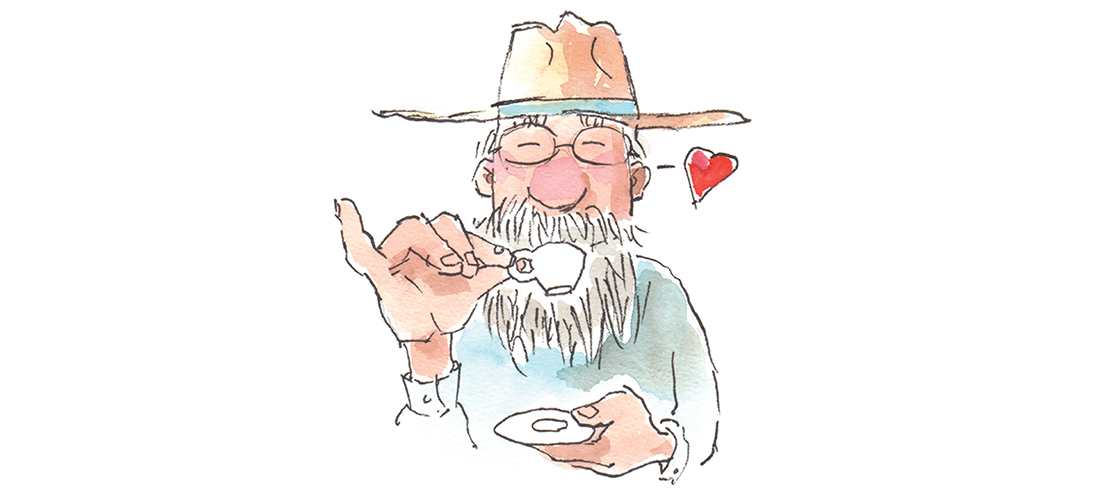

In 2018, I visited New Orleans for the first time. It’s a magical city, full of history and an old energy that cannot be described, only felt. It was where I received my first tarot reading — not from some Creole witch (missed opportunity, I know), but from an elderly white man with a calming presence.

I don’t remember his name now. I wish I did. I’m sure it was something like John or Mark. Ordinary, simple — fitting. He did a standard reading with twelve cards. The first eleven of them are a blur, but the final card — the card meant to represent me — still appears in my mind’s eye with crystal clarity: Juno, Queen of the Gods, a force to be reckoned with. That, and the reader’s parting words: “You are your own worst enemy. You can accomplish anything if you get out of your own way.”

I cried because I knew it was true. His words resonated, touching something deep within me that had been there all along, a continuing theme throughout my life. That’s what tarot does — it doesn’t tell you your future or some hidden secret of the universe. It points out what’s right in front of you that you’ve been too busy, too distracted to notice.

At the time, I struggled with anxiety and depression. I still do; I probably always will. But I got the message loud and clear.

I paid him via Venmo and left.

Fast forward to 2019, when a knee surgery plunged me into the deepest depression of my life, a depression that almost killed me. Key word: almost. I’m still here, winning battles against myself.

Those words, spoken to me years ago, still resonate. I knew in 2019 that I wanted to create a permanent reminder for when my depression would inevitably rear its ugly head again. This year, I finished that reminder with the help of Gene Cash at Seven Sagas Tattoo Studio.

I took a look at the classic Roman Juno and made her mine. I have a woodblock-style crane on my right shoulder that represents my first triumph over depression, so I thought, why not a Japanese Juno? Some of her classic symbols are still there: the peacock feathers, the spear, the moon, the lotus. The words beside her, written in Japanese, are a constant reminder to me: “watashi no kataki wa jibun.” My enemy is me.

But my favorite element of the whole piece? If you look carefully, the top line of the moon isn’t finished. It’s intentional, an aesthetic called “wabi sabi” in Japanese. It’s about appreciating beauty that is “imperfect, impermanent and incomplete” in nature. Fitting.

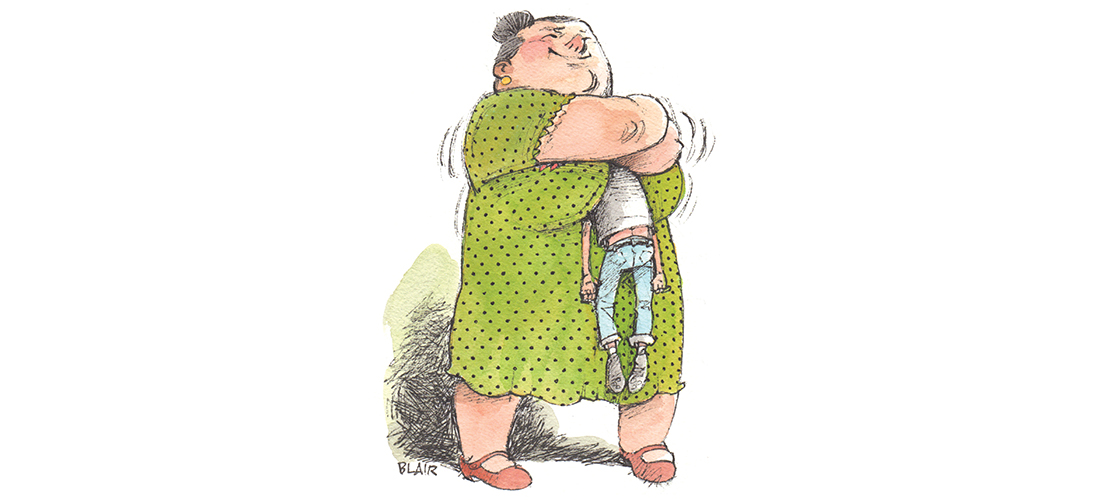

Juno is on my right arm to remind me that I am a goddess, capable of overcoming anything. So long as I believe it, I know I will.

To that tarot reader, wherever you are, thank you for awakening the divine in me. OH

A goddess with a gorgeous tattoo of Juno on her arm, Corrinne Rosquillo is a regular contributor to O.Henry.