O.Henry Ending

O.Henry Ending

The Chipmunk

An uninvited houseguest makes an imprint

By Marianne Gingher

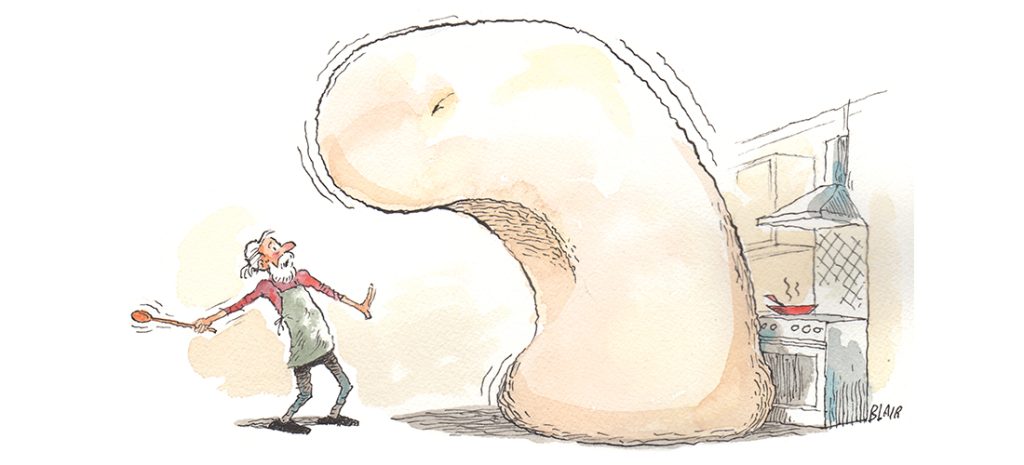

At the beginning of the 2020 pandemic, a chipmunk enters my house and will not be caught — not by my cat or the Havahart trap I bait with peanut butter. Day after day, she won’t take the bait.

Next, my 3-year-old dishwasher breaks. First world problem, a broken dishwasher, right? It seems a certain order is breaking down between appliances going haywire and wild animals invading my house. I call a repair service and am told that parts for this dishwasher are on backorder from Mars. No matter. I happen to be a dish washer — in the way I am not a stove or a refrigerator.

A month passes, pandemic time, so that weeks go by like years and years like weeks, and nobody can remember with any authority what happened when. The dishwasher is still broken, I know that much, and Chippy’s still on the loose. I hear her scuttling under the stove, shifting herself around to get ever more comfortable. Mornings, when I make coffee, I find tufts of insulation in front of the oven door, as if she’s been rearranging her furniture. She’s had a chance now to study my habits and my cat’s habits and hedge her bets as to when it’s safest to venture out. I find less-than-savory evidence of her adventures whenever I sweep. Once in a while, when I’ve been especially quiet, she’s skittered out and encountered me. She screams! I scream! Clearly, we are not meant to be roommates.

Daily, I bait the trap with fresh peanut butter, but catch nary a whisker. On warm days, I leave the backdoor open, hoping a sniff of fresh air will entice her to brave a jailbreak. Has her long captivity made her forget how to be a chipmunk? Has mine made me forget how to be human? My cat’s catness seems in jeopardy (since he can’t catch a chipmunk) and he looks depressed.

When the appliance man delivers the new dishwasher motherboard, he wears pristine coveralls, clean cloth booties over his shoes and a super-duper N-95 mask. He carries a large briefcase with all sorts of digital testers and gleaming repair instruments inside. He arranges all his tools on drop cloths and removes the dishwasher’s worn out organs with the care and precision of a surgeon. “A bit of bad news,” he says as he finishes tidying up. “I found small animal droppings under there. Possibly you have a rodent problem?”

That day, I go to the grocery store and, on a hunch (I’ve done some research), buy some pricey rabbit/gerbil/hamster food specifically “for rodents.” I have refrained from thinking seriously about the fact that Chippy is a rodent. I bait the Havahart with renewed determination and . . . voila! In the cage, she’s calm, cocking her little chipmunk head to observe me better as I carry her outside. I feel tenderly connected, like Snow White on the brink of a song.

The pandemic asked us all to get better at waiting. I marvel at the patience of the chipmunk who knew only the wild green flickering world before her estrangement from it. Trapped in a house, her immense aliveness had to learn to be still. She spent six weeks dodging a gargantuan human and Isis, the cat, gobbling any dusty crumb she could find, waiting, no exit strategy. During her lockdown, nothing was certain, except that the hawk who frequently glides over the neighborhood would not be picking her off. Wherever she scampered, I know she’s enjoying the pandemic’s easement as much as I am this summer. OH

Marianne Gingher has published seven books, both fiction and nonfiction. She recently retired from teaching creative writing at UNC-Chapel Hill for 100 years.