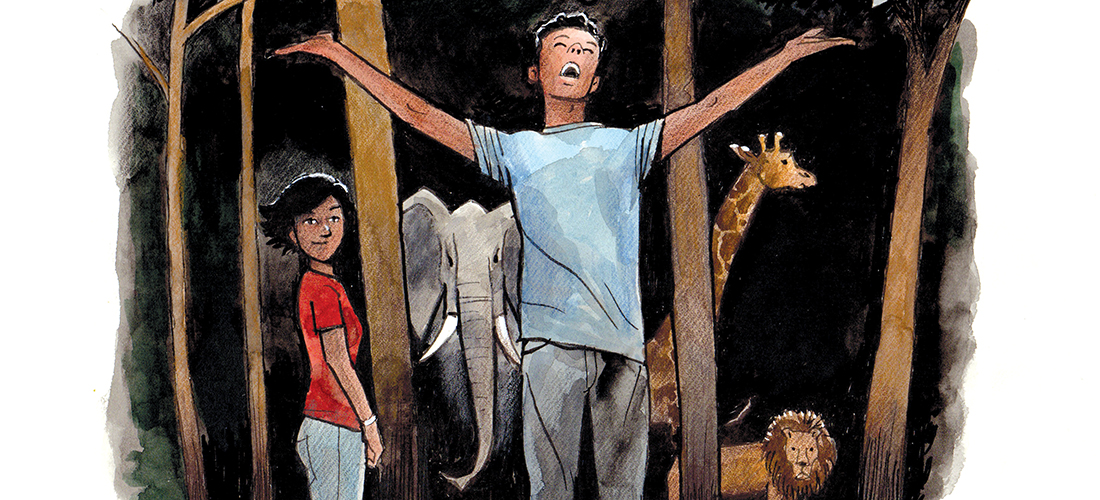

The Zoo

Fiction by Daniel Wallace

Illustrations by Harry Blair

We were listening to Vivaldi the night I died, the bed so soft, so warm, my wife of nearly half-a-century perched beside me with a cup of ice chips, there to wet my tongue, my lips. Even though I die at the end of it, this is not a sad story, really: I was very old, comfortable, cared for, weary and loved, loved my whole life long, ready to fade into whatever night was waiting for me. And of all the moments I might have conjured to accompany me as I was leaving, it was our very first date that I recalled.

Clara and I were grad students in English, just classroom friends, weeks away from defending our dissertations — hers on lute music in Shakespeare’s early plays, mine on Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein and the birth of modern science. I’d always liked Clara, but I think everybody did. She was smart but didn’t seem to care that she was, and made the rest of us — who were battling with each other, always burnishing the myth of our own brilliance — seem dumb. She was also funny, and the kind of pretty I was drawn to. Her nose was just a little longer than one thought it might have been, her eyes too big. They were emerald green, though, and rested on her big cheeks like marbles. Her knees were oversized for her long thin legs, like two snakes that had just swallowed one rabbit each. The truth was she wasn’t really picture-pretty at all, but carried herself as if she were, or didn’t care that she wasn’t, and that made her more beautiful than anyone I’d ever seen. She seemed wild to me, beyond anything I could ever capture. I was 27 and looked like a young man overly acquainted with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, by which I mean bookish in a sun-starved sort of way, shy around actual humans, shiny brown hair, still waiting for the peach fuzz on my upper lip to turn to fur. Somehow she let me know that she was free — “I’ve been kind of seeing somebody, but now . . . ” And she shrugged.

And there we were.

So we decided to go out for a beer one night. I picked her up in the first car I’d ever owned, an old Dodge Dart I’d bought used five years before, beaten and bruised, 210,027 miles and counting. There was a hole in the passenger side floorboard a mouse could have slipped through, and the engine was seriously flatulent.

“Nice car,” she said, hopping in. She was wearing jeans and a T-shirt, variations on which seemed to encompass her entire wardrobe. “Is it new?”

“Very funny.”

“Kidding,” she said. “But seriously, it’s a real car, right?”

“Ha ha.”

“I’m just having fun with you.” She punched me in the shoulder. “But honestly, want me to give it a good push? Happy to.”

She went on like this for a little while and stopped just before it became tedious. Maybe just a beat after it became tedious. But I was laughing. “For someone who doesn’t even have a car, you have strong opinions about mine.”

“I kid you,” she said. “But seriously.”

Off we went to a place called Brother’s, famous for its jukebox and onion rings and frosty beer mugs. We slipped into a booth and talked about what graduate students talk about — dissertation directors, anxiety, our cohorts and more anxiety. That was the thing: It was fine and fun and comfortable; we just got along so well. Even after a few minutes together it felt like we’d been coming to Brother’s forever and talking about nothing and laughing — when this guy appeared, an apparition materializing from the dark of the bar beyond us. Tall, wiry, a small face made angular by a well-trimmed goatee, and eyebrows like a mossy overhang. Our age. He was wearing a black jacket and a black T-shirt beneath it and black pants, and I’m assuming black socks and underwear as well. He sat down next to Clara — they clearly knew each other — and he smiled at me and shook my hand. A strong grip. Very strong.

Clara covered her face with her hands and moaned. “Jeremy,” she said, she sighed. “Jesus. Jesus Jesus Christ.”

Jeremy looked at me and rolled his eyes, like we were having so much fun and now Clara has to come and ruin it for us.

“I saw you and I had to say hello,” Jeremy said to her. Then to me, conspiratorially: “We were together, not too long ago. Clara and I.”

Clara nodded, but it was a grudging nod. I’m sorry, she mouthed to me.

Jeremy saw her. “You should be sorry,” he said.

“Please,” she said. “Jeremy. This is not the time or the place for this.”

Jeremy shook his head and shrugged. “I don’t know why. This used to be our place.”

“Our place?” She mocked him. “We came here twice.”

Someone put two quarters in the jukebox and “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” began to play. Clara looked at me. “We should go, Richard. This isn’t going to get any more fun than it already is.”

“Richard,” Jeremy said. “What a great name. May I call you Dick, Dick? Great. So, Dick, about how long have you and Clara been an item . . . Dick.”

I didn’t answer. I was in a difficult position: Clara and I really weren’t an item, yet; I didn’t feel it was up to me — or in my wheelhouse — to step up and eject the interloper from our midst.

But then, slowly, Jeremy’s smile dimmed and died, and he looked at Clara as if she were a hideous thing.

“You’re a coward, you know,” he said to her. “How could you just

. . . disappear? No call back. Nothing. Not cool. Not how you break up with somebody.” He looked at me, back to her. “Just . . . not cool. In case you didn’t know.”

She closed her eyes and took a deep breath, as if she were about to plunge underwater.

Slowly, she exhaled.

“We didn’t ‘break up,’ Jeremy. We were never even really seeing each other, not like that. We were never even — .” She stopped, giving up the postmortem. “Listen. I’m sorry, okay? I should have called you or maybe written you back to say thanks and everything, it was great while it lasted but a talent-free hobo novelist who doesn’t know the difference between a semicolon and an ampersand is just not what I’m looking for in my life at this time. All the best, Clara.”

Jeremy tried to rally with a comeback, but he didn’t have one. “I’m not a hobo,” he said. “Just . . . between places.”

“For a year and a half,” Clara said.

Poor Jeremy. He had been defeated. “Raindrops” ended and began again. Jeremy shook his head, stared off into the faraway-somewhere. He looked like he was standing on the shore of a deserted island watching the ship that was supposed to save him sail on by.

“Okay, well, I feel like it’s time for me to hitch a ride on the next prevailing wind! But before I go, I have a message for you, Richard. You’re going to be me one day. You’ll have the time of your life with this one. You’ll be so happy. It’ll be like the world went from black and white to color. Then everything will go to shit and you won’t be happy anymore because Clara will move on, and it will suck for you, just like it’s sucking for me now.”

By the look in his eyes he was taking a moment to relive some of the colorful times he’d shared with her, and he smiled. “But it will be worth it,” he said. “Because Clara . . . well, nobody is Clara.”

Then he stood, and just as quickly as he had come was gone, a shadow fading away into the darkness of the bar.

We paid up and left and walked to the car in the dusky quiet. We were a little unsettled.

A breeze ruffled the trees but fell short of the two of us, standing on either side of my car now in the gravel parking lot. No stars out yet but the moon was rising, low still and smoky white.

“Well, that sucked,” she said.

“Yeah. Yeah, but — ”

“But what?”

“You have to admire his pluck.”

“I love that word,” she said. “He’s not plucky, though. He’s . . . indecorous.”

“Unseemly.”

“Boorish.”

Looking down like there was something on the ground for her to see, her hair fell into her face and it was as if a big CLOSED sign went up. Even after she pushed it back behind her ears it was hard to really see her. “Jeremy,” she said. “Such a mistake. What if every mistake you ever made followed you around for the rest of your life? Like a parade of mistakes. The too-small shoes you bought, the undercooked chicken. Jeremy.”

“That would suck a lot.”

“I was mean to him.”

“He asked for it.”

“Really?”

I shrugged my shoulders. Maybe he did, maybe he didn’t, but I was on Clara’s side now. I looked back at Brother’s. I kept thinking Jeremy was going to follow us out here and stab me.

“I think we should make a mistake,” she said.

“Really?”

“We need to do something,” she said. “That or go home. And I don’t want to go home. Let’s do something stupid that will follow us around forever like undercooked chicken.”

“Sure,” I said, not really sounding like the devil-may-care-crazy guy she may have wanted just then. But what to do? I couldn’t think of anything: I’d always veered to the quiet, safe side of life. But she had an idea.

“You know what we should do?” she said. “Or what we shouldn’t do, I mean?”

She sat on the hood of the car and waited for me to join her. I did. This was as close as I’d ever been to her.

“What?”

“Go to the zoo.”

There was a small zoo in Bellingham, somewhere between a real zoo and a place where a bunch of animals had been collected from around the world and housed by a larger-than-life intrepid explorer in makeshift pens and a pit for lions and tigers, a skinny elephant, a fence for the giraffe, a cement island for the monkeys. The animals didn’t look abused, just disappointed.

“Great idea,” I said. “But it’s closed. It closes at dusk.”

“Who said anything about it being open?”

And she told me a story she’d heard, about an entryway at the bottom of the 12-foot-high metal fence, one you can slither through with ease, gaining access to the entire place. No alarms, no cameras. Just you and the animals in the dark.

“I know the way.”

“Sure,” I said, hoping to impress her with my newfound recklessness. I handed her the keys to the car.

“Really? Seriously?” she said, like a kid. “You’re up for this?”

Her face was so small I could cup it in one hand, and in the half-light of the parking lot outside of Brother’s she had the patina of a film from the ’40s. I think I was already in love with her. We got in the car and she looked at me, and it was as if she were saying, Are you ready? Because this is happening. If you’re going to wimp out this is your last chance. In just the few minutes we’d been outside night had fully fallen. A couple of frat boys came out of Brother’s braying at each other, and the tail end of a song comes out with them — “Raindrops.”

“Let’s do this,” I said.

She started the car and winked at me as she revved the engine. “Big mistake,” she said.

It was a terrifically muggy night but with the windows down I could feel a cool undercurrent to the air. I remember thinking that one day it would be fall, then winter, then spring and then summer again, and that whatever was about to happen will have happened a long time ago. The wind made Clara’s hair go wild, half of it flying out the window like streamers on a bicycle, the other half in her mouth and in her eyes, blindfolding her for seconds at a time. “I’ve got this,” she kept saying. “No problem.” Then she looked at me, mock-scared with a frightened smile, like the other part of her was saying, Don’t believe me! There is a problem! I don’t have this!

She took a sudden turn off of Greene Street, and then the road whipped around to the right, up and then down, the car beams breaking into what felt like a virgin dark. Just a pine tree forest, a forgotten road, nothing else.

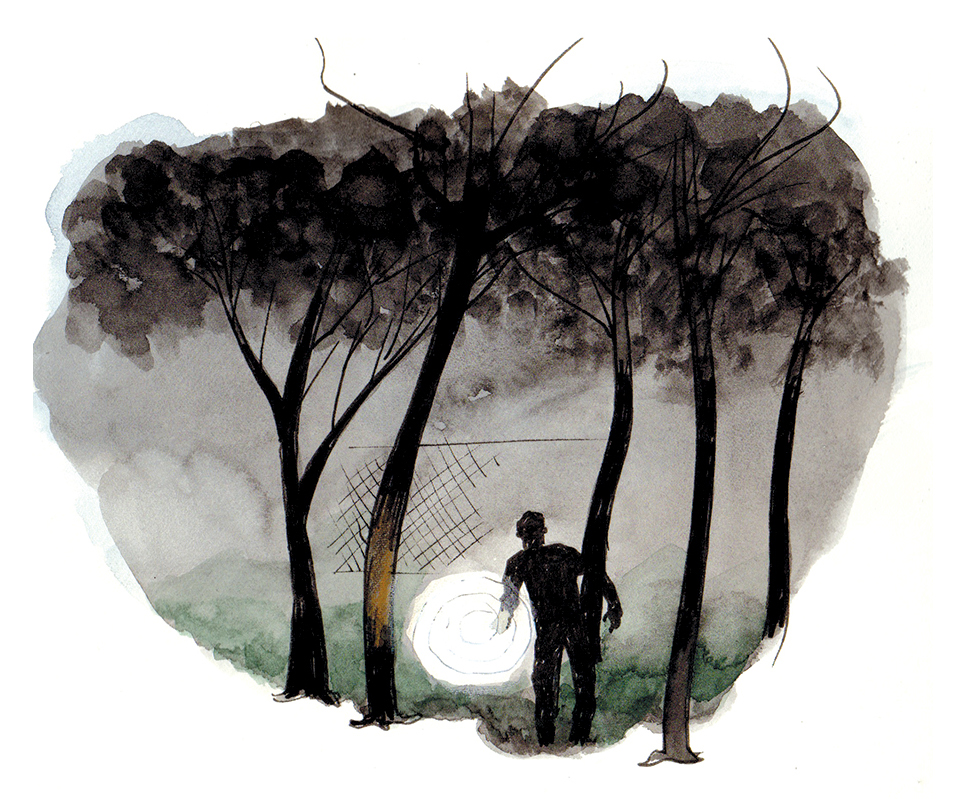

She pulled over to the curb and cut the lights and we were under the cover of night.

“We’re here,” she said.

Gradually the world around me came into focus, and over the trees I could see the throbbing red light at the top of the WRDC radio tower. I positioned myself in the world and I realized we were in fact right behind the zoo, near a farm, an overgrown pasture. She put the car in reverse, pulled back, angled it, then turned the lights back on, spotlighting the secret entrance through the fence. She raised her arms into the air, fists clenched: victory.

“You’re pretty impressed with yourself.”

“I am,” she said, nodding. “As I should be.”

She turned off the car and threw the keys back to me.

“It’s go time,” she said.

The hole in the fence was big enough for a mandrill to crawl through. We got in on all fours. Neither of us said a word but communicated through hand signals and raised eyebrows and then suddenly — What’s that? Oh. It’s nothing. Continue . . . inching through the inky dark toward the animal quiet.

The woods ended, and we were on a path, dirt and gravel first and then lightly paved uneven asphalt. A yellow light spilled on the elephant cage, that fenced-in patch of hard dirt no bigger than a poor man’s front yard. There was no elephant there now — he or she was sleeping inside. I’d been here a couple of times, thrown a few peanuts over this wall. Clara looked at me. She was so excited she seemed to be vibrating. She leaned in close and stood on her tiptoes to whisper-yell in my ear: “We did it!” She held onto my elbow. “But it’s important to stay quiet,” she said. “That way they won’t know we’re not one of them. They’ll do things most people never get to see them do.”

It turned out that animals in the zoo at night do what most animals do. They sleep. It was absolutely still. The elephants, the giraffes, the monkeys, the spiral-horned antelope — they were all asleep. You could hear them; it was the humming sound of a living forest. Blue-black shadows everywhere. An ibis had a bad dream and shrieked, and a striped hyena answered (maybe it was an ibis, maybe a hyena), then it was silence again. What lights there were were kept low, and the moon was hidden behind a cloud. It turned out that sneaking around in a zoo full of sleeping animals was not unlike sneaking around in a zoo with not a single animal in it. Clara thought she saw something and gave a little involuntary gasp and turned and — it was a rabbit. She shrugged her shoulders, smiled, but I could tell she’d had high hopes for this adventure. It hadn’t lived up to its hype. “We can go now if you want,” she said.

I did want to go. I wanted to be back in the car talking about what had just happened, how great it was and can you believe that we actually did that? Clara had no idea how careful I normally was, how meticulous with my life, had no way of knowing that I was a man who folded his pants at the crease and arranged his shirts by kind and, within kind, color, whose life-plan was to be invisible on command, to follow directions, to go as far as a man with a Ph.D. in Frankenstein could go. So yes, I wanted to leave.

But she was just too defeated.

If this were even our second date I would hug her, even kiss her until my kisses made her smile. A second date meant options. A first date, you couldn’t — I couldn’t — do more than take her hand. There was an old stone wall surrounding a duck pond, and I stepped up on it. It was only 2 feet high. Clara looked up at me and sort of laughed and said, “What are you — ?” but before she could finish the sentence I had my hand out and she took it and I pulled her up to stand beside me. “Listen,” I said. She listened and heard the same thing I did: almost nothing at all, just that humming sound. “Now listen,” and with my hands cupped around my mouth I shouted a quote from the book I had memorized: “Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.”

That did the job: The night blew up. The animals rose. Plodding out of his concrete bunker pounded the elephant, the curious giraffes loped into the moonlight, and the island of monkeys began to wildly chatter. Every animal was baying and woofing and screeching. The animal world had awakened — just for us.

“Richard,” Clara said, still in whisper-mode. Wings flapped in the dark above us, water roiled somewhere nearby. Clara grabbed my arm and pulled me close. Our shoulders bumped. “This is just . . . so great!” Her big eyes were wide, the size of saucers for a miniature teacup. The moon, the stars, the sky, the animals of the Earth, this beautiful woman, all here, before me — and I felt as if I had created a moment that had never been created before, never in the history of the world. And I was sharing it with Clara.

But I woke up more than the animals. The zoo actually had a keeper. I saw him before I heard him, the beam of his super-powerful flashlight bouncing off of everything.

“Who’s there?” he called out, in a deep voice. “You’re trespassing, assholes. And yes, it’s a felony, and yes, I will prosecute. Do not think I won’t. Course I’ll let you spend some time in the hippo pond first, goddamn it.”

He sounded tired, and very serious. This had gone too far for me, and for Clara. She was frozen against my side, had stopped breathing I think, statue-still. I took her hand and we jumped down from the wall. I had no idea now where the hole in the fence was, but what choice did we have but to try and find it? We ran into the woods. I scratched my face on the lower branches of a pine tree and could feel the stripes of blood across my cheeks. But we didn’t stop running. The zookeeper could hear us, of course, and shined the light into the woods following our path. “Come out come out wherever you are, moron,” he said gleefully. He followed the sound of us, sweeping his light through the forest, coming closer. I had no idea where we were. But we came to a huge tree, and I pulled Clara behind it, wrapping my arms around her until we were as small as two people could be. The light of his flashlight fell all around us, but not on us. We were that close to being seen — inches away from being caught and caged. But we were not.

He gave up. “Damn it,” he said to himself now, thinking we were long gone.

Then he turned around and headed back the way he came.

Still pressed up against me she looked up at me and smiled.

“You did it,” she whispered. “You saved us.” She kissed me on the cheek, but her eyes did not leave mine. “Richard,” she said, “that was truly magical.”

And I thought, I actually remember thinking this as we huddled together behind that tree: in 30, 40, 50 years — whenever she buried me — no matter what may have happened through the decades of our life together, this was what I’d remember, this night, the story she’d tell too many times to our children, our grandchildren, our oldest friends, the story of that night we broke into the zoo and woke everyone up. And not because it was the best thing that ever happened to us, but because it was the first. It set the tone, she’d say, for the rest of our lives. That night at the zoo we were in our own cocoon, arms encircled, closer than close. She burrowed into me, and we stayed that way for a while, longer than we needed to, until the night returned to its rhythms, until all the wild animals in the world went back to sleep.

So of course, out of all the moments of my life, this would be the one I chose to see me out.

I felt a chip of ice on my lips, a damp cloth on my forehead. I didn’t know if my eyes were open or closed, but it was all dark now, and getting darker. I found my wife’s hand and held it.

“Clara,” I said. “Oh, Clara!”

Yes, your name was my very last word, so sweet I said it twice.

“Clara?” Gwendolyn said, and she shuddered, seemed to freeze and harden as if she’d died herself. “Richard, who is Clara?”

And I might have told her, but it was a long story from a long time ago, and by then it was much, much too late. OH

Daniel Wallace is the author of six novels, including Big Fish and, most recently, Extraordinary Adventures. He lives in Chapel Hill, where he directs the Creative Writing Program at the University of North Carolina.