Life’s Funny

LIFE'S FUNNY

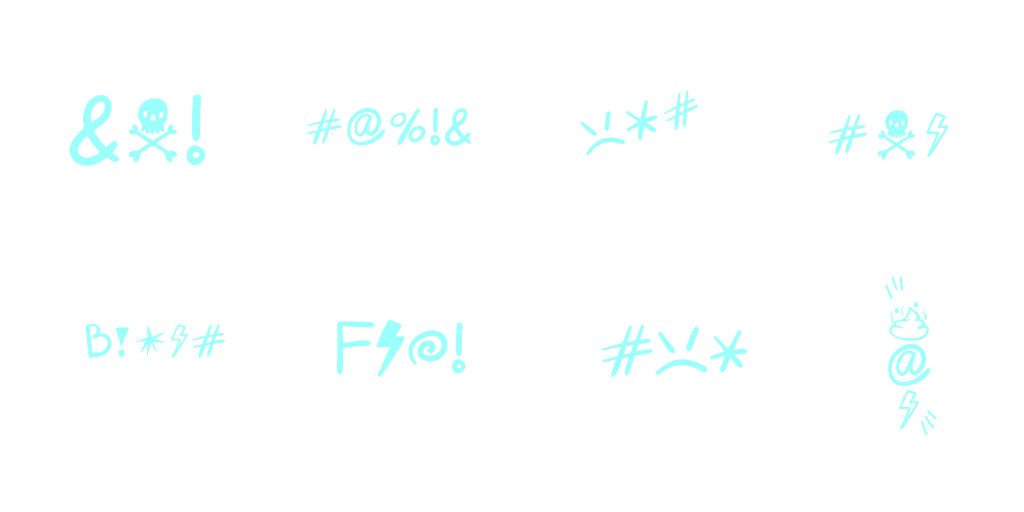

Well, Shhhhhhhucks

A potty-mouth clean-up is short-bleep-lived

By Maria Johnson

Algorithms are scary things, the way they learn our habits, which is pretty bleep well.

Why else would my newsfeed recommend that I read a piece in The New York Times titled “Curses! A Swearing Expert Mulls the State of Profanity.”

The story promises tips on how to cut back “if you want to.”

What the bleep does that mean?

I’m talking to you, algorithm, you little son of a software bleep.

Are you saying I have a cursing problem?

Well, you’d be partly right.

And partly wrong.

See, most of me is O-bleep-K with cursing. In fact, I love laying down a good oath. There’s a certain catharsis and clarity and energy that comes with damning a bleepity-bleeper to everliving bleep.

Bleep. I feel better just typing that.

But another part of me knows I curse out loud too bleep much, though there’s a camaraderie in hanging with other potty mouths. More on that later.

I also curse a lot to myself when I’m fired up about something, which is pretty bleep often. My awareness of this salty leaning has me thinking that maybe I’ll give up cursing for Lent.

How long is Lent?

What?!

Forty days?

Oh, bleep no.

I could maybe do 40 hours.

Like, one work week, from 9 to 5, with nights and weekends off. Sort of a Lent Soft challenge? Is that a sacrilegious question?

Yes?

All right, all right. Forty bleep days. Without spoken-word profanity.

Or swearing in writing.

But I get to write using bleeps, and I get to keep the sewer in my head.

It’s a start. I gotta do something because this habit is getting worse.

Maybe it’s because I’m an empty-nester. I watch my language around children.

As my grandmother used to say: Little pitchers have big bleep ears.

She didn’t use those exact words, but that’s what she bleep meant.

Because kiddos imitate what they see and hear, my husband and I minded our p’s and q’s — and f’s and s’s — because we didn’t want our sons to blurt out something disrespectful or insulting at the wrong time.

It takes time and maturity to learn how to curse responsibly.

Also, we didn’t want our boys to sound like they were raised in a bleep barn.

Now that our guys don’t live in our bleep barn, I mean house, anymore, I’m not as careful as I used to be. I’ve reverted to my pre-mom setting.

Actually, scratch that.

I’m worse than bleep ever.

Maybe it’s the times we live in.

Have you watched a movie or streamed a TV series lately?

The language is bleep atrocious.

Have you listened to a podcast?

Holy bleep.

Honestly, I don’t like it. But what the bleep am I gonna do? Cancel Max so I can’t watch Hacks any more?

Fat bleep chance. When Season 4 drops, I’m all over that bleep.

Yes, its profane and edgy. It’s also funny as bleep.

So let’s forget about me cutting back on consumption.

I do think there’s room, though, to cut back on my triggers. Namely the news.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m a newshound from the word “go.”

We need to pay attention to what’s going on.

But for the last several years, I’ve hardly been able to watch, read or listen to the news without hollering, “I CANNOT BLEEP BELIEVE THIS!”

I realize my venting doesn’t change diddly-bleep.

But I gotta tell ya: It feels pretty bleep good.

I’d like to clear up one misconception right here: that people who curse a lot don’t have a very good vocabulary.

That’s a load of bleep. I’m not saying that stupid bleeps don’t cuss. But not everyone who cusses is a stupid bleep.

To wit, I do the Spelling Bee every day.

And Wordle.

And a crossword puzzle.

That’s a lot of bleep five-dollar words.

Plus, I’ve been around writers most of my life, and writers are some of the finest cussers I know. We have the verbal palette; many of us just favor the blue hues.

What the bleep?

Maybe this Times story can explain.

Where are my bleep glasses?

Oh, here they are.

Let’s see. Looks like they interviewed a guy named Timothy

Jay, who’s a retired professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.

Get this bleep: His specialty was studying profanity.

What a bleep fun job that would be.

Ol‘ Timothy says that cursing is indeed more prevalent because society has gotten way more casual.

He blames social media because you can just about write anything on TikTok or X, the platform formerly bleep known as Twitter.

(Aside: When someone comes up with a better verb than “tweet” for the act of reacting with one’s thumbs, please let meknow. I refuse to say: “Gimme a minute to X this.”).

Anyway, Tim says culture is always evolving and just as soon as a taboo becomes acceptable, people will come up with something even taboo-ier.

Translation: Don’t hold your bleep breath for cursing to go away.

He goes on to say that cursing is mostly about conveying intensity of emotion, and not always negative emotion. In some cases, swearing around others indicates belonging and intimacy.

It’s like saying to someone, “You talk like a bleep sailor, but I love you anyway. Also, I trust you not to record this and play it back for my mom.”

The good professor notes that humans get a measurable physical jolt out of swearing.

Roger that bleep

Finally, he says that the only way to curse less is to practice mindfulness about when you curse and why.

Sigh. That’s what AI said, too, when I asked it.

It said to try practicing meditation and yoga instead of cursing.

That’s a lot of bleep Oms.

And box breathing doesn’t charge my battery like swearing does.

I’m thinking my best course of action is to use more curse word substitutes.

Like dang. Or dog. Or freakin. Or fiddlesticks. That’s an oldie and a goodie.

Yeah.

Fiddle-bleep-sticks.

I like the sound of that.