Omnivorous Reader

Omnivorous Reader

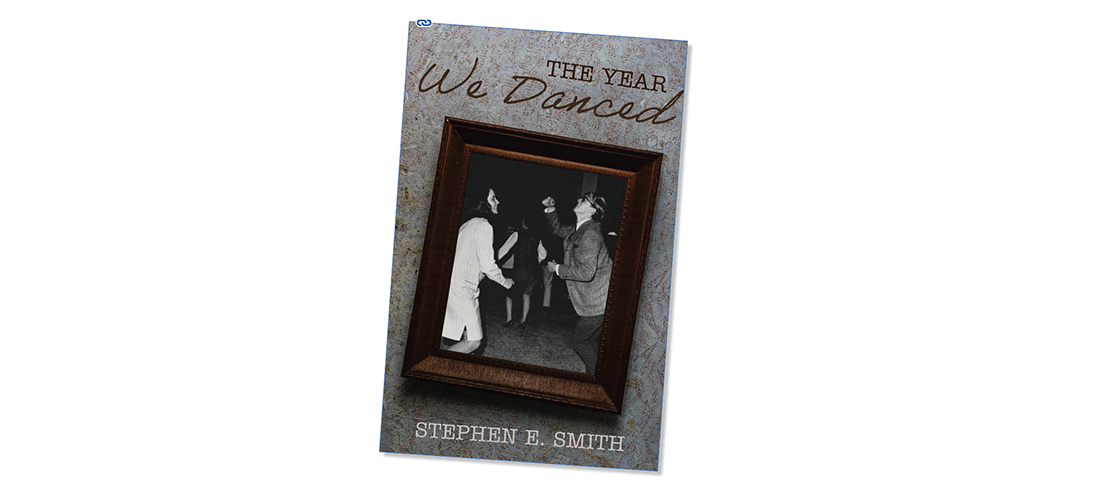

Sweet Memories

A year on the journey to adulthood

By Jim Moriarty

My freshman year in college was nothing like the one Stephen E. Smith writes about in his memoir The Year We Danced. And yet it was exactly the same.

For any memoir to rise above the level of that dusty old book sitting on the mantel in your grandchildren’s house, it has to reach a level of universality — no easy feat — and The Year We Danced does it without breaking a sweat. Except on the dance floor, that is.

Written with a touch of humor and a bit of heartache by one of North Carolina’s finest poets, Smith’s tale of his freshman year at, then, Elon College in 1965-66 is sweet without being sentimental, poignant without being preachy. While simultaneously being tethered to and free from his family back in Maryland, and with the escalating war in Vietnam a kind of constant buzz in the background, The Year We Danced is nothing less than the launchpad of a life, a survey course in Adult 101 — complete with its own soundtrack. Along the way we’re introduced to an endlessly entertaining cast of characters, drawn by Smith in distinctive, rich detail.

Smith’s father, the boxing coach at the U.S. Naval Academy, had taken control of his son’s college admission process in March and delivered the results in June like an uppercut:

“We were devouring Mrs. Paul’s fish sticks and oven-baked frozen French fries smothered in Hunt’s ketchup, our standard Wednesday evening fare, when he stared at me across the dinner table and stated matter-of-factly, ‘You’re going to North Carolina in the fall.’

“I froze in mid-bite, a flaky chunk of trans-fat-engrossed fish stick balanced on my fork. ‘I am?’

“‘Yeah, you’re going to Elon College,’ he continued. ‘It’s far enough away that you won’t be running home every fifteen minutes.’”

We are introduced to Grandma Drager, who “never forgave her wayward first husband and never passed up a chance to deliver a sermon on the evils of drink,” who travels 350 miles by bus to hand-deliver to a young man about to venture forth into the world a baffling bit of wisdom in six words, memorable only in their towering insignificance — “Promise me you’ll wear tennis shoes.”

Once at Elon, where Smith’s father delivers both him and the message that he doesn’t expect his son to make it through the first semester, Stephen meets his roommate, Carl, who has arranged his shoes in the closet alphabetically by brand and has a pricy collection of 30 or 40 bottles of men’s cologne in parade formation on top of his dresser. “Unfortunately, Carl was the loquacious sort. He was going to sign up for physics and run for class president in addition to majoring in German. Then he started in on his personal life. I had no choice but to lie there in the dark and listen to him brag about his girlfriend, who was a freshman at a college in Virginia, and how they were going to get married before the year was out, a notion that struck me as utterly demented.”

As it turns out, it becomes clear rather quickly that Carl could have benefited from one, or several, of Grandma Drager’s exhortations on demon rum. “In the time we shared room 218, Carl never once exchanged his sheets for clean ones, and the pile of dirty laundry on his desk had spilled onto the floor beside his bed and included many of the garments he’d so neatly arranged in the closet on the first day of orientation. He’d sold off most of his bottles of cologne for beer money, and, as nearly as I could determine, he’d quit going to class altogether.”

On the plus side, Carl became the subject of an essay written by Smith for the spine-chilling professor of English 111, Tully Reed. Smith picked a subject he knew and wrote the hell out of it. When the “The Making of a Derelict,” with copy as clean as anything that ever ran in The New Yorker, gained nothing better than a C– (the highest grade in the class), Smith screwed up the courage to find Tully in his office and ask the fearsome man why.

“‘It’s not A or B work,’ he said, shaking his head, ‘not for a college freshman.’ He handed me my essay, took a drag on his Lucky Strike and returned to slinging red ink.”

Smith’s dance partner, and surely one of the first honest loves of his life, is Blondie, an upperclassman (they weren’t gender neutral in 1965), who can power drink a PBR and dance until curfew, if not dawn. At their favored club, the Castaways, she takes flight. “As I watched, the simple truth dawned on me: We might be at a club where there was only one acceptable dance step, but if Blondie didn’t want to dance the Shag, she didn’t have to. She was beautiful, unique, and she didn’t give a damn about attracting undue attention. She wasn’t there to prove herself to anyone; she was there to have a good time, and she intended to do just that.”

Also unique, and on the other end of the spectrum from the fearsome Tully, was another English professor, Manly Wade Wellman, a prolific author who would eventually call the Sandhills home, just as Smith would and does. “Wellman was barrel-chested and wide-shouldered, his graying hair combed back from his broad forehead. His round, open face was accentuated with heavy eyebrows and a prominent nose below which was cultivated a tweedy, slightly skewed Clark Gable mustache. What was immediately appreciable was the peculiar way in which his eyes reflected light. The very tops of his dark irises flickered, suggesting an inner illumination. . . . If Wellman was insistent, he was also endearing. I was immediately convinced that this guy had a sincere interest in who I was and what I thought. He wanted to know about my latest writing project as if it were of immense concern to the literary community. ‘What are you working on?’ he asked.”

In a few short months, Smith had met both the carrot and the stick.

In the end, Blondie moves on. As all of our Blondies do. Then Smith gets the news that a boyhood friend has been killed in combat. “The spring of ’66 was early in the war, and although the weekly casualties were the highest since our involvement in Vietnam, I doubted anyone at Elon could name a friend who’d died in that distant war. I kept the news to myself.”

But not the sense of helplessness and futility. “I reviewed the times Barrie and I had spent together, my memory sliding from one image to another in no particular sequence — the hours playing hide-and-seek on dusky evenings in the little town of Easton, Maryland, the summer days I visited with him in Salisbury, where we skipped stones from the banks of the Wicomico. But what I remembered most vividly was a summer afternoon in 1957 — we were both eleven — when Barrie and I were singing our favorite top ten rock ‘n’ roll songs and I mentioned that I was fond of a country song, ‘The Tennessee Waltz.’ ‘I can teach you how to play it on the piano,’ he said, and then he sat down at the family’s upright Baldwin and with uncharacteristic purposefulness showed me how to pick out the melody on the white keys. It was a good moment to hold in memory, affirmative and focused, his casual smile, his fingers walking along the ivories.”

Smith’s memoir, to be released this month by Apprentice House Press, is packed full of good moments. If you know someone who is going to be a college freshman — or if you were ever young once yourself — this trip down memory lane is well worth taking. OH

Jim Moriarty is the editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.