Years ago, when our sons were little, they gave me a Mother’s Day gift.

Their eyes gleamed as I peeled away the wrapping paper.

“Oh,” I said, aware of the tender hearts in front of me. “A LEGO set. How . . . cool!”

“Look, Mom!” they bubbled as they grabbed the box from me, flipped it over and pointed to pictures of all of the things that could be made with the multicolored bricks. “Isn’t it great?”

“It is great,” I said.

And I meant it. Because I knew how they meant it. Inside that box were hours — OK, maybe minutes, considering my impatience and their facility with LEGOs — of a shared experience, of making something together.

They knew I would be down, as in down on the floor, with anything they wanted to do. That was a compliment that I treasured. And, honestly, whenever I went with their flow, I experienced the joy of knowing them more deeply, of learning something new and, often, of cracking up at the result of our collaboration.

Fast forward to the moment when I unwrapped a gift from my husband, Jeff, on our recent anniversary.

“Oh,” I said. “A solar-powered . . . Bluetooth-enabled . . . motion-activated . . . bird-cam-feeder . . . equipped with AI identification . . . and a voice alarm. How . . . cool.”

His eyes were gleaming. Once installed, the bird-cam-feeder would be easily the most technologically advanced device in our home. OK, just outside our home.

I realized that the gift represented something we could do together, even though he’s way more into birds than I am. Plus, I had to admit his choice made sense, given the events of the past year. To wit:

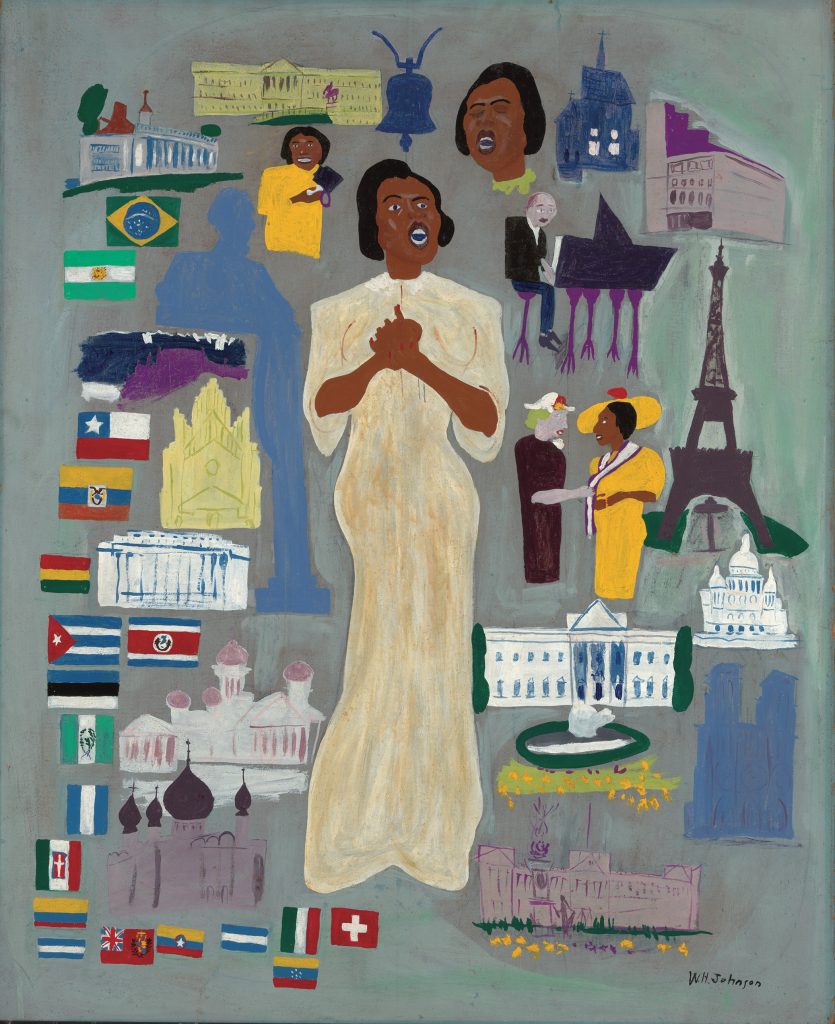

I did ask for, he did give me, and I did love reading Amy Tan’s nonfiction work, The Backyard Bird Chronicles, a beautifully illustrated book about how Tan survived COVID by becoming an intense observer, and sketcher, of birds.

I do luvvvvvv watching, and re-watching, the adventures of avid birder and ace Detective Cordelia Cupp in the brilliantly absurd Netflix series, The Residence. (Seriously, Netflix execs, what are you thinking by not renewing that show?)

I did express enthusiasm, in a polite way, when a friend described his bird-cam-feeder equipped with AI identification.

Also tangentially true: I have been known to commit aspirational gifting. Consider the pickleball paddles I gave Jeff a couple of birthdays ago. (“Look, honey! Aren’t they great?!” I said, rising from the table to demonstrate my dinking technique.)

But back to our fine feathered friends: Basically, I like watching birders more than birds, which is why I enjoyed watching Jeff carefully determine the best location for the bird-cam-feeder, in front of our garden Buddha, who understandably wears a slight smile.

He — Jeff, not Buddha — spent many hours figuring out how to mount the bird-cam-feeder (atop a black metal pole); how to make the couplings aesthetically pleasing to me (no radiator clamps allowed); and how to use the app that would notify us whenever the camera spotted a creature.

The first sightings, I must say, were of some truly scary specimens: The Sweaty-Headed Sucker Pluckers.

That’s right. Us. The camera picked us up every time we walked by, headed to the garden to pinch the suckers from our tomato plants.

Jeff tweaked the phone-based app settings to detect only creatures that alighted on the feeder. At first, I was amazed at the different birds that stopped in for a beak full.

There was our friend, the cardinal.

And a purple finch.

And a house sparrow.

And a Carolina wren.

And a thrush.

And a titmouse.

And another titmouse.

And, OK, another titmouse.

And then came the crows.

Oh. Em. Gee.

The crows.

Here, I would like to make a prediction: When the world as we know it comes to an end, it will not become the the planet of the apes. No. It will become the planet of the crows, an obviously superior species that knows how to work together for mutual benefit.

I say “obviously” because once they discovered the bird-cam-feeder, it was a nonstop milo-millet-cracked-corn-and-sunflower-seed hoedown in our side yard.

You know how revelers toss beads from floats in Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans?

Like that. Only instead of throwing beads, the captain of the Crow Krewe would hop up on the perch, bob side to side, and sling seed to all of his crow buds on the ground until, voila, no more beads.

I mean seeds.

This happened over and over again, until Jeff went into the app and figured out how to sound the alarm to scare off unwanted diners.

BZZZZZZ! Gone.

We were satisfied. For a minute. Then we noticed that the feeder would be full of seed at sunset and empty in the morning.

Hmm. Most birds around here, owls notwithstanding, do not feed at night.

Further, the camera recorded no birds overnight.

But something was triggering the camera to record blurs.

We went into Cordelia Cupp mode, zooming in on the fuzzy photos frame by frame until we spotted a hand. But not just any hand. A hand worthy of a 1950s horror flick. A small, gnarly, five-fingered black hand surrounded by a cloud of fur.

“Barnacle goose,” AI declared.

Huh?

A few frames later, we observed a closeup of sharp little teeth.

“Bonin petrel,” said AI, suggesting a seabird that nests on Pacific islands.

A few frames later, we made out a bushy tail.

“Mute swan,” AI ventured.

A few pics hence, we saw a pointy snout with a sliver of a dark mask.

We didn’t care what the AI bird brain said.

It was a raccoon.

We looked at each other. But how?

We dived into the literature and found out that raccoons have thumbs, which means they can grasp things, like aesthetically pleasing black iron poles, and climb said poles, hand-over-hand, past dome-shaped baffles, to arrive at sunflower seed jackpots.

Nom-nom-nom.

Suddenly, we were aware of a pattern, not that it mattered.

About this time last summer, we were engaged in the War of the Chipmunks, a dramedy that pitted us, the innocent homeowners, against the rally-striped varmints who maintain a thriving chip-o-polis around our home.

This year’s instant classic was the Battle of the Birdseed, starring that insidious urban bandit, the raccoon, which, in truth, I would have been tempted to think of as cute, if not for the fact that it was cleaning out my bird-cam-feeder, which I was suddenly very possessive of.

Ask any politician about the unifying emotions of people who feel they are threatened by “others,” even if the others are, you know, raccoons.

The fortification began.

Problem solver that he is, Jeff hopped on the internet to search “raccoon baffles.” He found one model, a wide-mouth, metal pipe that no raccoon could get a grip on, for $60.

His Scottish heritage — best paraphrased as, “By God, I’ll not pay $60 for a two-foot length of stove pipe”— prompted him to drive to a rural hardware store to buy . . . wait for it . . . a two-foot length of stove pipe for $20.

Which meant that very night I hit “Place Your Order” on the $40 skin cream I’d been dithering about for weeks.

It’s yet another way that we balance each other.

But I digress.

The point is, after many more hours at his workbench, Jeff installed the homemade raccoon baffle, and now we are now the proud owners of a maximum-security bird-cam-feeder, which is highly effective.

How do we know?

The morning after installation, there was plenty of seed for the morning feeders.

And, upon closer inspection, we saw that the stove pipe was covered with muddy, five-fingered handprints that appeared to be sliding downward.

(Insert sound of raccoon fingernails scraping black stove pipe, followed by sharp-toothed expletives.)

We looked at each other and cracked up.