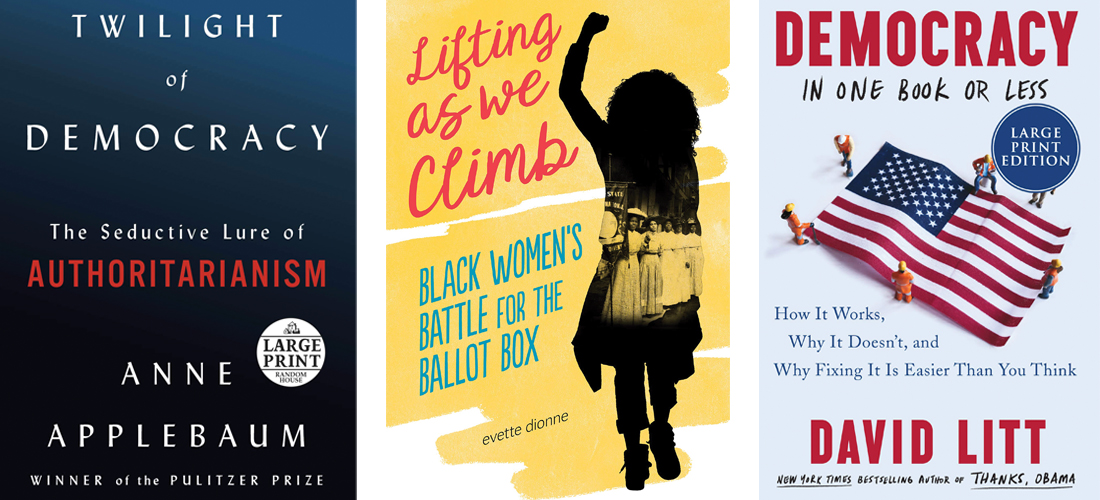

Hooked on summer reading

Let’s be honest, who among us sails on through the master class on whale anatomy if Herman Melville doesn’t write “Call me Ishmael” right out of the blocks in Moby Dick? At the top of every writer’s job description is the ability to kidnap the reader’s imagination and keep it, at least for a while. Since everything in the Year of the Pandemic is cloaked in a bit of the unknown, our Summer Reading Issue of 2020 is all about capturing imaginations. Who better to learn from than seven of the best writers North Carolina has to offer? And who better to help them then seven terrific artists and photographers? Some of these great beginnings were written specifically for this issue, some are the first few words of books appearing in stores near you soon, and others were just kind of kicking around on laptops. Each one is designed to grab your attention and hold it. Feel free to fill in the rest of the story yourself. — Jim Moriarty

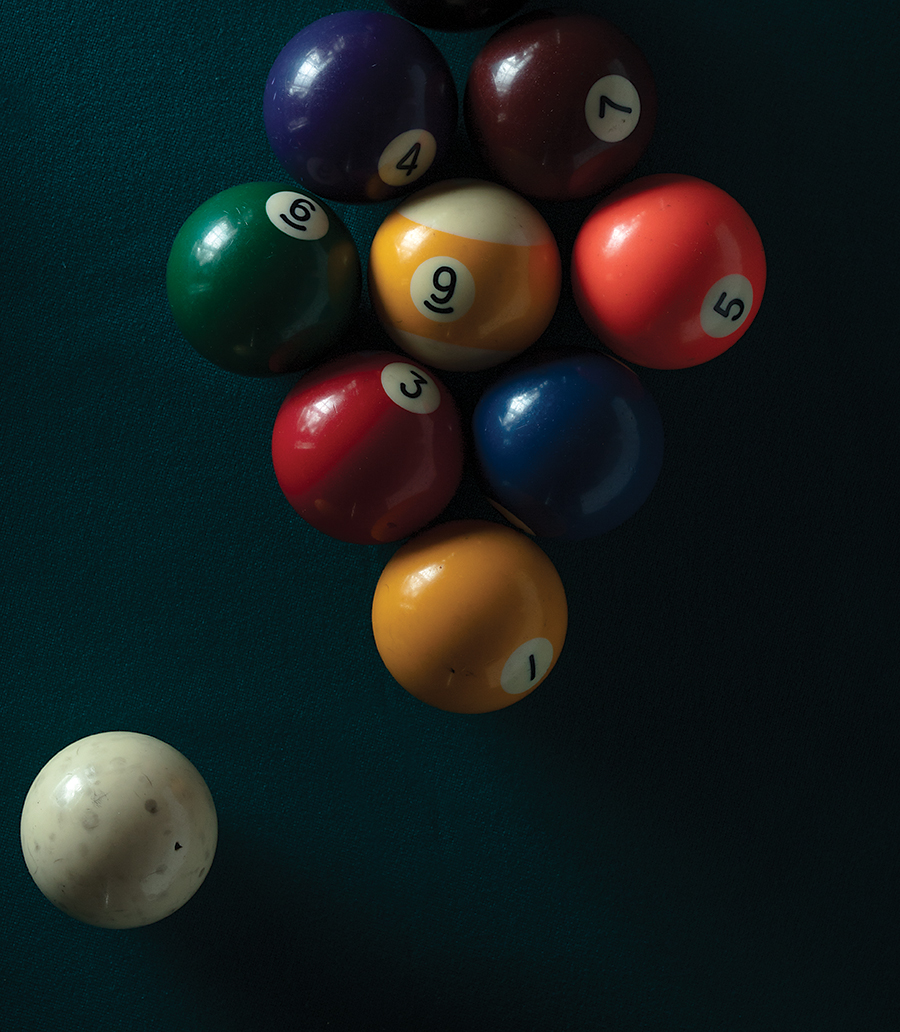

Why I Love Pool Halls

By Bland Simpson • Photograph by Mark Wagoner

From the open upstairs windows of a plain two-story commercial building overlooking a bricked side street, Colonial Avenue in Elizabeth City, as a boy I used to hear the pouring out of loud jolly talk and laughter but most of all the hard clicks of cue balls breaking the racks, and spoken and sometimes shouted encouragements and disappointments, and the lighter clicks of wooden scoring beads, as men I could not see slid them along strung wires above the green felt-covered slate pool tables in that magic room above. A small sign hung by the streetside door, stating simply:

City Billiards, Home of Luther “Wimpy” Lassiter, World Champion, 9-Ball.

In the nearby corner movie theater, the Center, my friends and I often sat, enthralled and forgetting we were only a hundred yards from a swamp river on its way from the Great Dismal Swamp to the sound and the sea, believing instead that we were riding along on horseback as we wove with the cowboys through some saguaro range or that we were stomping or swinging along with Tarzan of the Jungle through mamba-snake-ridden equatorial brakes. We even saw Zsa Zsa Gabor there, in Forbidden Planet, and knew this short interlude of imaginary space travel had brought us to our worshipful knees before the most beautiful and powerful woman in the Universe.

Yet when we emerged from these diversions, our riverport reality fell heavily upon us, and the sounds of smack and click kept spilling out from the pool hall on high, and we somehow knew that was where the real men, not boys, went to have their adventures, though all we could do, our ages still in single digits, was to stand on the sidewalk below and listen hard and try and make out what the hoots and hollers and howls, and the cussing, were all about, and what they all really meant.

Bland Simpson is the Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, the author of nine books, and a longtime pianist and composer/lyricist for the Tony Award-winning North Carolina string band The Red Clay Ramblers. In 2005 he received the North Carolina Award for Fine Arts.

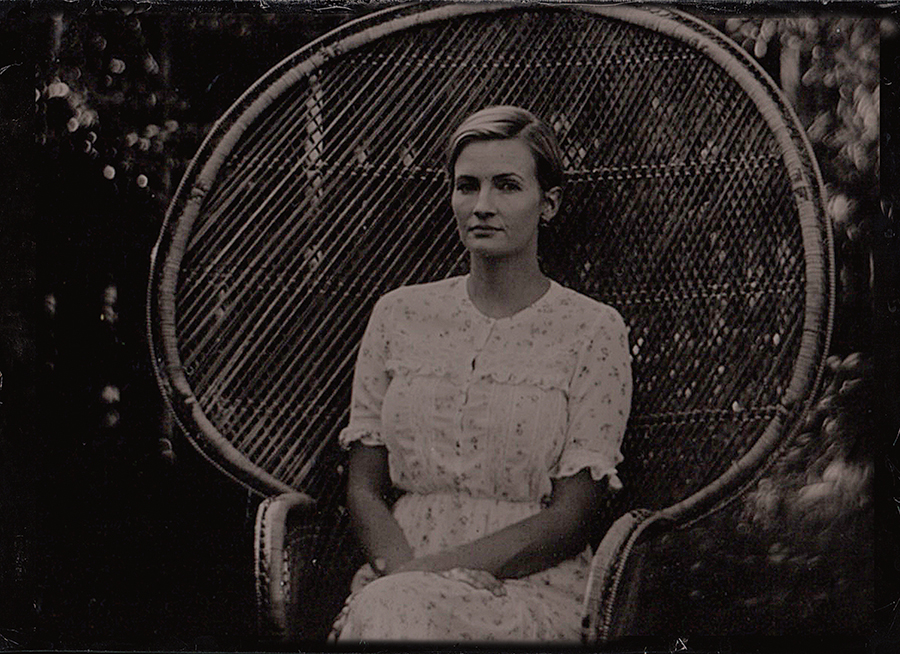

The Pressing Spirit

By David Payne • Photograph by Laura Gingerich

And Jacob was left alone; and there wrestled a man with him until the breaking of the day. — Genesis, 32:24

One minute I’m asleep, the next it’s as if the roof’s collapsed and pinned me under tons of rubble. Except it’s not the roof. The weight isn’t external; it’s inside me somehow. I’m paralyzed and pinioned. The greatest effort I can muster sets one eyelid aflutter, lets me crook — just barely — the digit of my index finger. And it isn’t dead, this weight, it’s living. There’s something with me in the bed, and not just with me, on me, and not just on me, in me.

I fight and strain, and suddenly like someone with his shoulder to a door when the door flies open, I’m bolt upright in bed. What happened? What the fuck just happened? Sweat pours off me. Silver in the silver moonlight through the shutter, steam rises from my shoulders in 40-degree air of the unheated bedroom. Boom! says the surf outside my window. Boom! and Boom! again like the percussion section of an orchestra. And I’m alone here, alone in this unheated, flimsy summer house that thrums and trembles like a spaceship on the launch pad as the January gale blows off the ocean. The roof’s intact, there’s no intruder. The bedroom door I closed when I retired is still latched the way I latched it, from the inside. Yet for a moment, several, staring at that door, I have the sense that it, It, whatever pinned me, is still here, just beyond, listening as I listen, breathing as I breathe, aware of me, as I’m aware of It.

Who’s there? I call.

No answer.

David Payne is the author of five novels and the 2015 memoir Barefoot to Avalon: A Brother’s Story, which The New York Times called “a brave book with beautiful sentences on every page.” A founding member of the Queens University of Charlotte Master of Fine Arts program, Payne also taught at Bennington College, Duke University and Hollins University. He recently completed a screenplay of Barefoot to Avalon for the Oscar-nominated director Giulio Ricciarelli.

The Last Wedding

By Frances Mayes • Illustration by Laurel Holden

The wine spilled. As I reached across the table, my sleeve grazed Austin’s glass. The big Brunello globe fell over in a quick crash. Dark, that carmine red spreading on the embroidered linen tablecloth. Austin stood up so fast his chair tipped backward. He found two napkins on the sideboard and helped spread them over the stain. Instinctively, I glanced at Annesley as her mouth fell open. She knew I’d spent the afternoon lavishing my attention over every place card and dessert spoon. I moved the flowers and water carafe over the napkins. “Doesn’t matter, Kate, good as new,” Austin said. He has unusual eyes. Hazel, I guess, but it’s the way he looks at you rather than their color, as if he’s surprised to see you. But glad. I had the odd thought that he might say I see you. Do you see me? I rinsed his glass in the kitchen and refilled. All solved, except not.

Frances Mayes is the celebrated author of the No. 1 New York Times bestseller Under the Tuscan Sun: At Home in Italy. A poet, essayist, author and professor, her recent works include Always Italy from National Geographic Books and See You in the Piazza: New Places to Discover in Italy. Her excerpt is the opening of a new book, The Last Wedding.

Being the Record of Hannah King,

born April 14, 1681, Salem Village

By Lee Zacharias • Photograph by Andrew Sherman

I was a girl, you understand. I had a girl’s sins. I wanted to know whom I would marry. We all did. Would our husbands be rich, would they have land? What would be their trade? Though Reverend Parris preached against magic as a trick of Satan, we knew ways to tell the future. And if we were predestined, what could be the harm?

I was 11 that year, two years older than the Reverend’s daughter Betty, the same age as her cousin Abigail, who lived with them. Abigail was an orphan. Many of the girls who would be afflicted were living as maidservants with relatives or others who might take them in, Mary Warren with the Proctors, Elizabeth Hubbard with Dr. Griggs, Mercy Lewis with the Thomas Putnams and their daughter Ann. Only Mercy knew who her parents were. They had been killed by Indians at Casco Bay, and for a brief time she stayed with the Reverend George Burroughs, who survived. How she came to Salem and the Putnams no one knew, but we could guess. Reverend Burroughs had once been pastor of the Salem Village Church, but he had left for Casco Bay in dispute over his salary, forced to borrow money from Thomas Putnam, who was known to hold a grudge. Mercy was older, as were Mary and Elizabeth, 17 or 18, old enough to marry, but orphaned girls had no dowries, and the question of the future was of much urgency to them, for if they failed to marry or displeased their masters, they would have nowhere to go.

The salary for Reverend Parris was also in dispute. The church in Salem Town accepted the Half-Way Covenant, but in the Village, Reverend Parris feared the Devil was among us and refused to baptize any child whose parents had not testified to how God had shown Himself to them. Only the converted could be members of the church. It was brutal cold that winter, with much snow, but the villagers refused to supply the Meeting House or Parsonage with firewood, and they argued with church members whether their tax revenues should be used to pay his wages. Betty was a sensitive girl, and though she was but 9, perhaps she too feared for her future.

I was drawn by curiosity alone, for I lived with my parents, brothers, and one sister. Surely my dowry was secure. And though I was marked, for underneath my shift there was a small brown mole near my hip, not so different from the marks of Satan that the Court of Oyer and Terminer would soon look for on the accused, that small spot was my secret, and I kept my secrets well, just as I kept Betty’s.

It was Abigail persuaded her. First they tried the scissors and the sieve, but when Goody Parris opened her basket, she did not find her scissors as they were, and she blamed their servant Tituba, the strange, dark-skinned woman Reverend had purchased in Barbados when he was a sugar merchant there. Nor were the girls discovered after they tried the Bible and a key, but neither sieve nor Bible yielded answers, and so they turned to the Venus glass. It is known that the shape an egg white takes when it is dropped into a glass of water will reveal your future husband’s trade. A plough foretells a farmer, a ship a man who sails the seas. Instead, Abigail saw a coffin, which caused her to faint dead away. In her fright, Betty became forgetful of her chores, her mind apt to wander during prayer, and when Reverend rebuked her, she fell into fits. They say she barked like a dog, crawled about the floor, and writhed most hideously. Abigail too took fits, but Reverend’s prayers failed to cure them, and he summoned Dr. Griggs, who could find no disease and concluded that they had been bewitched. When Reverend forced them to reveal who had possessed them, they named Tituba, the beggar woman Sarah Good, and the outcast Sarah Osborne, who was feuding with the Putnams over an inheritance.

Tituba was examined first, and she confirmed the spectres of both Sarahs. Despite the faults in her English, the confession she delivered to the court held such power that many of those present trembled as if stricken or fell to the floor. She did not will to hurt the children, she insisted. A tall, white-haired man in a black coat had forced her to torment them lest she die. She had looked upon the Devil, who took many shapes, a big black dog, a hog, black and yellow rats, a yellow bird. Again she said that she had seen the spectres of Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, and over the next weeks the afflicted girls, especially Thomas Putnam’s daughter Ann, would name many more. Once a month all that summer we gathered upon Gallows Hill to watch the witches hang, including Reverend Burroughs, whom Mercy had accused. When he recited the Lord’s Prayer upon the gallows, some protested he must be innocent, but he was not spared. All of the hanged pled innocence, though Giles Corey refused to plead and was pressed to death instead, which is more grievous to endure.

But I have not yet told my part. I was a strong girl. I did not swoon or fall into fits. Neither accuser nor accused, I kept my secrets, that hidden mark, and this: for I too had gazed into the Venus cup, where I saw not ship, not plough, nor coffin. What I saw was a book. But I could not tell from the shape of it whether it was a Bible or that other book where the Devil made his minions sign their names in blood. I knew not whether I would marry a man of the cloth or pledge my troth to Satan.

Lee Zacharias is the author of three novels, a collection of short stories and a collection of essays. Her most recent novel, Across the Great Lake, was named a 2019 Notable Michigan Book, took a silver medal in literary fiction from the Independent Publishers Awards, and won both the 2019 North Carolina Sir Walter Raleigh Award and the 2020 Phillip H. McMath Book Award. Her fourth novel, What a Wonderful World This Could Be, will be released in June 2021 by Madville Publishing.

Rosalie Goodbody

By Celia Rivenbark • Illustration by Harry Blair

Rosalie Goodbody had been thinking lately when she woke up and felt every awful second of her 83 years that her last name was God’s ironic joke. But then she remembered, as she brushed her own teeth, stooped over the idiotic glass sink her son in Colorado had decided she needed on one of his rare visits home . . . God didn’t give her the name “Goodbody.”

No, that honor belonged to her dead husband, Raymond, whose own body had been slowly twisted and tortured with a combo platter of arthritis and being “bad to drink.” Dead at 66. Goodbody indeed.

So here she stood in her pink Walmart mules and a bright aqua housecoat she’d paid too much for just so she could talk to the nice lady at QVC, Rona something, spitting toothpaste with a pink tint of blood in it into this stupid sink. Damn this sink and damn Carl, who had flown in for just a couple of days.

Rosalie had thought they’d talk, at last, about Cliff. What were we all going to do about Cliff? But Carl had had other ideas, ideas involving ridiculous glass sinks from Lowe’s that sit on top of the vanity instead of down in it like God intended.

God. There was that name again. Rosalie realized that she was thinking a lot more about Him these days and whenever she did, she thought of Him in capital letters because to do otherwise might risk some kind of backlash. God. Him. Where was He, anyway? Didn’t He see how tired she was?

It was almost time to wake up Cliff, a chore she dreaded every single morning. She lingered for a moment, thinking that if she flossed, she could put it off for a few more minutes. But she’d seen the blood in the sink, so it was probably better not to stir up anything else.

Cliff was her big, retarded grown-up son. There was no nice way to put it so, for more years than she liked to think, if Rosalie saw someone eyeing them oddly in the Piggly Wiggly or wherever, she would just smile big and false and say, “Yes, that’s right. He’s my big grown-up retarded son and I love him!”

Cliff would just grin, of course, when Rosalie made this pronouncement to a total stranger whose only sin had been to stare a half second too long. Cliff was much more interested in the way a shipment of beach balls was contained in this elasticized box on the end of the canned meats aisle. Looking around first, Cliff pulled on the elastic, pinching it good, making all the balls jump a little inside their rubber corral. He did it a few more times until Rosalie reminded him that they still had a few more things on their list and didn’t he want her to get those nice Duncan Hines frozen brownies?

Good Christ, Rosalie thought to herself while running the same wide-toothed Goody comb she had used for more than two decades, through her sturdy gray hair. Good Christ but those brownies were her salvation some nights.

If Rosalie was being honest, and she really was most of the time except when she was talking to the cable company and said she only had one month to live and didn’t want to spend it watching a snowy picture of The Young and the Restless (you shoulda seen ’em move; everyone should try it), she loved Cliff more than Carl.

Celia Rivenbark is a New York Times bestselling author of seven humor collections, including You Don’t Sweat Much for a Fat Girl and We’re Just Like You, Only Prettier. Rivenbark writes a weekly political humor column syndicated by Tribune Media Services and is an award-winning playwright. Her next play, High Voter Turnout, will be staged in Wilmington in the fall of 2020, pandemic permitting.

What the Cat Knew

By Ruth Moose • Illustration by Emery Tiptoe

Under her feet the black cat lay curled. Occasionally he twitched his tail and half opened one eye, let the green of it shine meanly. The cat knew the girl in the chair was asleep; her breathing was slow and even. Sometimes she jerked her legs or let out a small, soft snore.

The cat knew the noise he had heard was not a normal one for this house. It was not a clock tick, nor chime, not the rackety dump of the icemaker, nor hum of the furnace.

The cat knew the footsteps that followed that small squeak when the front door opened did not belong to anyone he’d ever heard before.

The cat raised his ears.

The footsteps stopped, but there was the dull thud and a metal click of something heavy dropped in the hall.

A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, three Pushcart nominations and the Sam Ragan Fine Arts Award, Ruth Moose taught creative writing at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill for 15 years, tacking on 10 more at Chatham County Community College. Her fifth collection of short stories, Going to Graceland, was published by St. Andrews Press in 2020. She is the author of six collections of poetry and two novels, Doing It at the Dixie Dew and Wedding Bell Blues.

Die Trying

By Michael Parker • Photograph by John Gessner

Carthage, Texas, 1973

Because his clothes were line-dried, they smelled to Earl of sun, grass, earth. But the girls on the bus said he smelled like creek mud. It was worse in the winter when he wore parkas donated by the Kiwanis Club coats-for-kids drive, easily recognized by the fake fur collars, which reeked of the kerosene used to heat their house.

At home, his family treated him like a second cousin much removed. “Oh, look, Earl,” they’d say after he’d been sitting quietly in a room for a half hour. He knew he was creek mud to them, too. And so he refused celery filled with peanut butter and dotted with raisins, because, seriously? Ants on a log?

Into the smoke from neighbors burning their trash in rusty barrels slipped Earl, on the lookout for someone to whom he might define himself. But he always ended up in the woods, listening to the transistor radio his father had given him, or reading aloud from the biography of Leadbelly he carried with him always.

His people were proud Louisianans transplanted across the border to Carthage, Texas. His father was vaguely around. His mother talked all the time to her sisters in Bossier City, installing a 20-foot cord on the telephone so she could sit outside on the front stoop and smoke and ask her sisters about the fates of various men she might have married instead.

Prison, preacherman, gay, career military, meth-head, Port Arthur were the answers Earl imagined coming across the line. “Shoo now, Earl,” said his mother when she caught him snooping.

His father, when he worked, laid pipe. He claimed to be Acadian but his mother said he was out of Lawton, Oklahoma. Wherever he was from, his brothers and cousins soon arrived in Carthage and a compound of trailers and vehicles sanded down to primer or missing bumpers or outright wrecked beyond repair sprung up in the piney woods on the outskirts of town. Earl’s father once took him on a walk through the woods to a pond, where he taught him the words to “I’m so Lonesome I Could Cry.” Even when he disappeared for weeks, Earl had his transistor radio, on which his father claimed to have listened to stations out of Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Matamoras, Mexico, when he was a boy in his bed at night. Is there anything in the world more romantic than listening to radio stations from other countries illicitly after lights out?

Michael Parker was born in Siler City, North Carolina, and grew up in Clinton. He is the author of 10 books of fiction and taught in the Creative Writing Program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for 27 years. He currently lives in Austin, Texas. His excerpt is the beginning of his new book, Die Trying.