In the field with the Piedmont Bird Club

By Jim Dodson

Not long after sunrise on a crisp spring morning, a dozen members of the Piedmont Bird Club gather in the graveled parking area of A&T State’s University Farm on McConnell Road. Bundled in fleece jackets and gloves, ranging in age from 25 to 75, the group buzzes with the excitement of a class reunion.

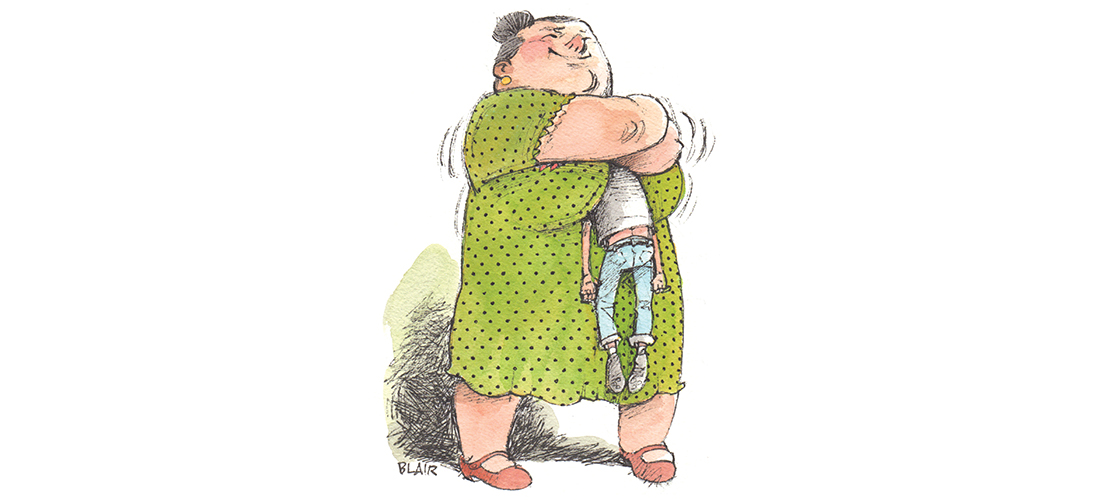

“It’s always a little like this,” explains the outing’s coordinator, Lynn Moseley. “Part of it is the usual anticipation of seeing new birds for our lists. But it’s also the simple pleasure of seeing other members that we haven’t been with in quite a while due to the pandemic. Birding is something that brings people from all walks of life together — especially now.”

At a time when everything from bowling alleys to churches shuttered, traditional outdoor activities like hiking, gardening, golf and birdwatching have experienced a surge of popularity.

Moseley, retired T. Gilbert Pearson professor of biology at Guilford College, has led birding safaris around the world for decades. She points out that public interest in birdwatching can’t come a minute too soon, especially given the startling news from the journal Science last September that, since the 1970s, North America has 3 billion fewer birds — or roughly 30 percent of the total population — due to habitat loss and other environment-related factors.

The findings from the most comprehensive study ever conducted on North America’s 760 species of common birds revealed that numerous groups, including sparrows, warblers, finches and blackbirds, were particularly hard-hit. The report singled out the threat to shorebirds, noting that some species face the prospect of extinction.

Which is why, says Moseley, organizations like the Piedmont Bird Club and local Audubon Society chapters are working hard to expand awareness of the problem and promote interest in learning about bird life. “On the positive side,” she adds, “even over the pandemic, we have seen growth in membership and interest in our monthly online Zoom programs. The good news is that the Piedmont has always been home to a lot of dedicated and passionate birders.”

In part, this explains why the Piedmont Bird Club is one of the state’s oldest birding organizations, founded by a group of dedicated, but loosely organized, UNCG professors (then Woman’s College) who were concerned about cats endangering the Gate City’s wild bird populations. Upon learning that the city council only considered proposed ordinances from organized groups, the professors formed the Piedmont Bird Club in February, 1938.

In its early years, club members worked closely with Guilford County Schools to organize bird-house-building contests and promote public education about wild birds, eventually partnering with the T. Gilbert Pearson Audubon Society (now one of ten chapters of the National Audubon Society in North Carolina) to expand public appreciation of local bird populations and the importance of preserving their natural habitats, earning Greensboro early designation as an official Bird Sanctuary.

When former Greensboro mayor Carolyn Allen moved to the city from Texas in 1962, as she puts it, “my husband, Don, and I knew the difference between a cardinal and a blue jay, but that was about the extent of our bird knowledge. But when a colleague from the college invited Don and me to a meeting and on a field trip with the bird club, that all changed in a hurry. We quickly got hooked. The club members were wonderful and the diversity of birds in this state was incredible.”

Half a century later, Allen is still an active member of the PBC, which today boasts close to 300 members across the Triad, many of whom also belong to the local Audubon chapter that’s named for the famous UNCG conservationist who helped found the National Association of Audubon Societies, now the National Audubon Society.

Under the guidance of early members like Margaret Law and Etta Schiffman, the Allens joined the ranks of hundreds of Triad birders whose passion for birds grew exponentially from the club’s many educational programs and frequent field trips around the state and region, including participation in the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count and North Carolina’s annual Spring Count, which typically happens each May.

“We’re blessed to live in a place where so many species of migrating birds come through during the spring and fall,” notes the former mayor, whose birding passion — like that of many members — led the Allens on birding trips across America. “I don’t think I’ve missed a Christmas or spring bird count since 1964,” she adds. Her daughter, Emily Talbert, is also an active and knowledgeable PBC member who participates in the annual counts.

Like most dedicated birders, Allen keeps track of wild birds she’s seen on field trips or in her yard near the Bog Garden in Greensboro. Still, she admits she’s not a “bigtime lister” like many of the current club members who travel extensively to see, record and photograph species in the wild. “That’s the beauty of the Bird Club,” she adds. “You have several reasons people belong to the club. Some are competitive birders who are devoted to adding to their life lists — meaning birds they’ve seen in the wild — while others like me just enjoy being out in nature and in the company of people who share a love of birds. The social aspect is also important.”

“Once birding gets into your bloodstream,” agrees Ann VanSant, “it’s impossible not to fall in love with watching and photographing birds.”

On this early spring morning, the group is venturing down a gravel track to a farm pond where there are hopes of catching a glimpse of several species of rare ducks and possibly even the elusive Wilson’s snipe.

VanSant and her partner, Dr. Roberta Newton, both of whom retired from top teaching posts at Philadelphia’s Temple University and relocated to Greensboro in 2011, turned their hobby into a sweet obsession that’s taken the pair on birding expeditions to every continent on Earth. They are currently on a quest to “bird” all 100 of North Carolina’s counties.

“We’re up to 93 and counting,” explains Newton, a former professor of physical therapy. “Covid slowed us down a bit, but we’re getting back in the swing of things. Every place we bird is interesting because the birds are so different anywhere you go. Each place changes with the seasons and the annual migrations. So there is always something exciting to see.”

VanSant, longtime professor of pediatric physical therapy, is the team photographer, having captured thousands of spectacular images of wild birds in their travels. She credits growing up near a wildlife sanctuary on the New Jersey coast and watching the seasonal return of snow geese with her father as a starting point of her love affair with wild birds.

“Once you get the right equipment,” she says, “the fun really begins. There’s always the hope of getting the perfect shot of a rare bird for your list, but even the common birds are magnificent. You never know what you are going to see through the camera lens. That’s half the adventure.”

Matt Wangerin, chair of the club’s field-trip group, is a 20-year birder who has photographed birds from Alaska to Costa Rica. The digital revolution in camera technology, he says, has made wildlife photography much more accessible to birders of all skill levels. But cost of cameras, spotting scopes and high-quality binoculars can run well into the multiple thousands.

“There’s no question that digital photography has changed the popularity of birding, attracted more people than ever to the hobby — which, for some of us, really verges on a true obsession. The quality of the photography of many of our members proves that.” He points out that members regularly submit their photos to the Cornell University’s famed Lab of Ornithology for identification of bird species.

Lee Capps, a retired print broker from Burlington, has been photographing birds since 1981, having started his casual hobby with a 35mm Sears, Roebuck & Co. camera, shooting birds in his backyard and over the fence at his neighbor’s feeders.

“The digital revolution really changed everything for me,” he explains. “When Canon came out with its first digital camera around 2006, I used it in my printing business but eventually the birds took it over.” His original Canon recently expired, having taken more than 184,000 photographs.

Capps went on his first PBC walk in 2017 and was pleased by what he discovered. “The members were great, very welcoming, like birds of a feather,” he quips. “They’re also very knowledgeable about wild birds and always eager to share what they know. I’ve learned so much on those walks. They know the best sites around for seeing wild birds.”

Capps is a frequent user of the club’s highly active website for posting his pictures. “Anytime I can’t identify a bird I’ve shot, I post online and within minutes I get seven or eight members responding who can identify the birds. Part of the pleasure,” he adds, “is posting photography you know others will appreciate and respond to.”

These days, he rarely misses any of the club’s bird walks and even took up kayaking on the Piedmont’s lakes to get closer to water birds, netting spectacular shots of osprey, eagles and cormorants. “Currently,” he explains, “Lynn Moseley and I are both keeping up with an osprey nest on the bridge over Lake Mackintosh, hoping to get shots of any babies.”

On organized PBC field trips, which the club puts on several times a year around the region, Matt Wangerin is something of an eagle-eyed interpreter, able to identify birds by their various calls.

During the walk down to A&T State’s farm pond, for example, he points out the call of a red-shouldered hawk from the nearby woods. Sure enough, it soon appears, cruising for its breakfast high above the farm’s pastures — when Wangerin spots a kestrel sunning itself on a fence post.

Upon his word, members halt and binoculars rise in unison. Tripod scopes zero in on the bird and cameras click. Wangerin hears the call of an Eastern meadowlark and the process repeats itself.

Down at the farm pond, northern shoveler and hooded merganser ducks are seen and photographed along with the elusive Wilson’s snipe, which sends a palpable charge into the faithful, including a handful of newcomers out for their first bird walk. As the day warms and the birds begin to appear, so does the lively conversation among members, young and old.

“The social aspect of birding is really a major attraction for many of our members,” says outgoing club president Stella Wear. “To share a love of nature and beautiful birds is a wonderful thing, especially at a time when birds are so endangered. It’s this kind of shared awareness that can make a big difference in their preservation.”

Anna and Jerry Weston agree. The retired teaching specialist and lawyer have been dedicated members of the Piedmont Bird Club and T. Gilbert Pearson Audubon Society for many years. They’re also keen kayakers, backpackers, native plant enthusiasts, Sierra Club members, yoga fans and hikers who log at least three miles per day.

“This is the first time we’ve been out since last March,” explains Jerry as the group heads off for the demonstration fields across McConnell Road, where hopes of seeing pipits and killdeer are high. “It’s nice to get back into the outdoors . . . feels almost like a liberation.”

“Watching birds is a wonderful way to feel liberated,” Anna picks up on a theme. “You see them fly and it reminds you of what a wonderful place this world really is — and why we have to protect it.” OH

For more information about local birding with the Piedmont Bird Club, visit www.piedmontbirdclub.org.