The energy level in the room rises as an effusive man sporting a spiky, bleached-blond hairdo, bug-eyed welder’s goggles and a bright-orange lab coat tromps around stage, whipping up the crowd.

“YAH???” he hollers to the assembly.

“YAH!!!” the audience roars back.

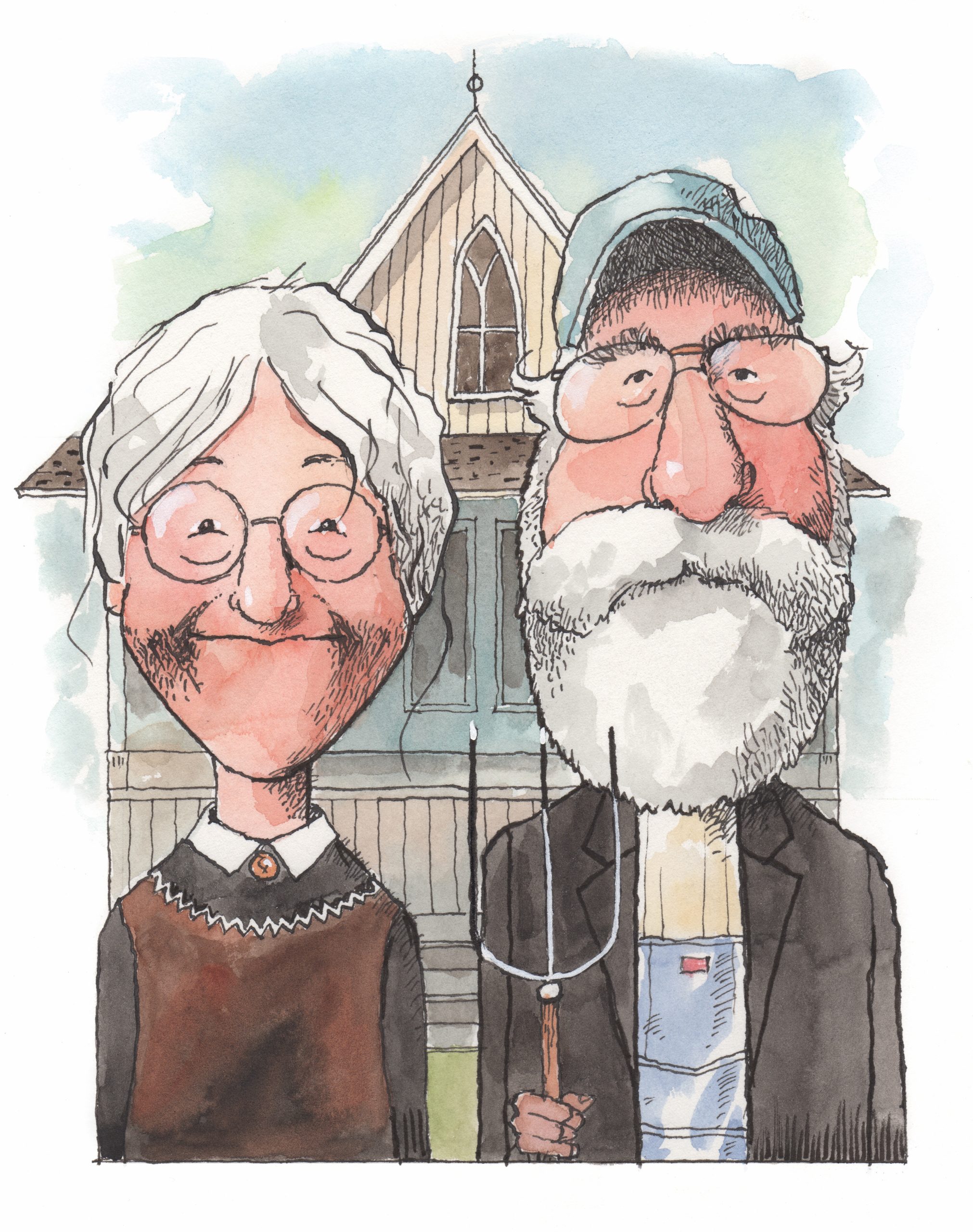

It’s the kind of joyful call-and-response you might expect to hear at a tent revival, but the leader is not a pastor; he’s Doktor Kaboom, the kooky-looking scientist character created by Charlotte native and UNCG alum David Epley.

This month, Epley — who haunted the area around Tate Street as a student in the ’80s — will bring Kaboom to Greensboro’s Carolina Theatre.

Alexandra Arpajian, who is relatively new as the theater’s executive director, booked Epley’s act because she thought it would fit Greensboro’s family-friendly vibe. The show also matches her plan for the historic venue.

“Part of the mission of being a nonprofit is to develop the next generation, not just as theater goers, but as empathetic children who are ready to go into society,” says Arpajian, who also happens to be the mom of a 4-year-old daughter.

Her goal jibes with Epley’s knack for wrapping important life lessons in a veneer of playfulness. He instructs audiences to yell “Kaboom!” back at him whenever he bellows the word. The result is a chain reaction of silliness.

“KABOOM!”

“KABOOM!”

“It’s a verbal explosion of the character’s passion,” says Epley, a thoughtful and articulate guy who explains his alter ego in a telephone interview as he drives between gigs in Colorado.

“It’s really fun because, half the time, someone in the audience yells, ‘Kaboom!’ before I do.”

At 59, Epley is glad to return to the state where he was born, never mind that his Wikipedia page says he was born in Germany. That error is a testament to the believability of his character, who speaks with a German accent and assures the audience that he hails from the Rhineland.

In fact, Epley, whose heritage is mostly English and Scottish, was born into a middle-class family in Charlotte. His mom was the personnel manager of a large printing company. His dad was a photographer.

Meanwhile, Epley was in the basement, fiddling with chemistry sets, taking apart mechanical devices and putting them back together. In high school, he was one of the “smart kids.” Teachers flagged him as a prospect for the then-new North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics in Durham.

Epley spent his junior and senior years at the school for advanced students. There, he took rigorous classes from Ph.D.-level teachers.

“It was a wonderful, magical gift from the state of North Carolina to the students who went there,” Epley says, noting that many of the school’s alumni have gone on to prestigious careers in the arts and sciences.

Bored by one class, he and some classmates made up funny personas and attended class as their characters. Afterward, they roamed campus, still in character. Some teachers did not appreciate the comic relief. Others loved it.

“A lot of people just wanted to support whatever artistic expression these weird little kids were coming up with,” he says. “That’s where I found out that I really loved performing.”

After graduating and logging a stint in the Army Reserve, he headed to UNCG to study chemistry with the idea of transferring to Duke University or N.C. State for biomedical engineering.

A funny thing happened on the way to the lab.

Epley took some acting classes in UNCG’s renowned drama department.

“I knew nothing about acting I just knew that I was enjoying it,” says Epley, whose after-class memories include eating at New York Pizza, hanging out at a bar called The Last Act and working at Crocodile’s Cafe, all along Tate Street.

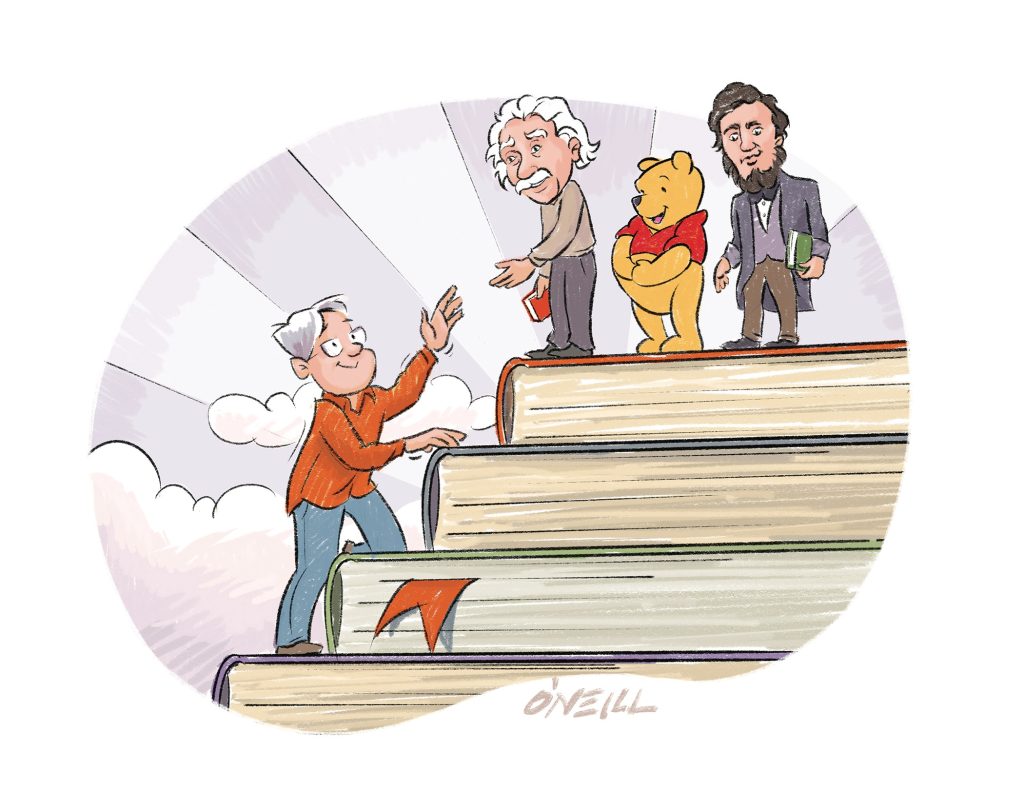

He switched majors and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts. Then and now, he scoffs at the idea that people who are good scientists can’t be good artists and vice versa.

That belief, he says, has made programs devoted to STEM — science, technology, engineering and math — fall short of their potential over the last 20 years because the best scientists are also creative thinkers.

“STEM is a lovely thing to focus on, but we’ll end up with a nation of lab technicians,” he says. “If we support creativity, then we become a nation of innovators.”

It took Epley a while to figure out how to blend art and science into a career.

For nearly 20 years, he and a troupe of comic actors known as Theater in the Ground traveled the country performing at Renaissance festivals.

“Imagine the Marx Brothers doing Beowulf,” he says.

He grew more serious about comedy when he became a father in his late 30s. He needed more income, a show he could manage by himself and a shtick that would fill performance halls.

That’s when he invented Kaboom, the embodiment of his first love, science, combined with his second love, stagecraft.

To prepare, Epley listened to hours of native German speakers on compact discs. He honed his character on the streets of Oswego, N.Y., during the Sterling Renaissance Festival.

After one performance, an older lady stayed to talk with Epley, who remained in character.

“After about 40 minutes, she goes, ‘I’m talking to you because my father was German, and he passed away when I was in my 30s, and I hadn’t heard his voice again until today.’”

The thought of that encounter still gives Epley goosebumps today. But the interaction that really hit home happened a few years into Kaboom’s road show.

He brought a kid on stage and began his usual patter.

“You’re a smart kid, yah?!” He asked.

The kid replied no, that he wasn’t smart.

Epley dropped to his knees and looked directly at the boy.

“I said, ‘You are smart. That’s why I picked you. I can see it in your eyes.’” he recalls.

Then Epley turned to the crowd: “Listen, if anyone ever asks you if you’re smart or creative or clever, don’t say no. Look them right in the eye and say, “YAH!” I worked with that boy until he was saying that and meant it . . . That’s when I learned I could do more than science and humor. I could teach empowerment. If I hadn’t found that, I probably wouldn’t still be doing this. That’s the aspect that brings me the most joy.”

Of course, there’s a strong dose of education in Epley’s show.

Kaboom talks about the importance of the scientific method, of testing hypotheses, of getting repeatable results. He uses everyday chemicals and oversized props to make things fizz, whiz, foam and pop. He uses a slingshot and a banana to great effect. A demonstration with dry ice yields a “controlled explosion.”

Inspired by the challenges that students faced during COVID, Epley’s latest show, which is titled Under Pressure, demonstrates how pressure can be channeled — both physically and emotionally — to make positive things happen in science and life.

Commissioned by the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, where Epley took the stage as Kaboom last year, the production is being pitched to streaming apps as a family-centered comedy special.

His shows are aimed at students in grades three through eight, but his comedy has drawn kudos as entertainment for all ages.

Comedian Dave Chappelle, who was once a neighbor of Epley’s young family in Yellow Springs, Ohio, took his children to Kaboom shows, and he supplied a glowing blurb before Epley’s first appearance at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in Scotland.

“We watched our neighbor transform into this incredible character,” writes Chappelle. “He was funny! And fun for the whole family.”

Epley believes his current show represents his best work, which comes at the right moment in U.S. history.

“I think science is being disregarded,” he says. “Television and talking heads have created doubt in people’s minds about expertise, which I think is absolutely damaging the country . . . So I really think what I do is timely and important. We’re all in this boat together, so let’s paddle in the same direction.”

Yah?

Yah.