12 Days of Christmas

A Dose of Happy

A Fresh Take on Faux for the Holidays

Tag Archives: 2023

With a touch of love, the ordinary becomes extraordinary

By Cassie Bustamante • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Shortly after moving into her Oak Ridge home, Tasha Agruso got an idea. An awesome idea. A wonderful, awesome idea — to create what looked like apartment entries out of her daughters’ side-by-side doors. Armed with door knockers, mailboxes, wreaths, doormats — even a lantern Tasha rigged with a battery-operated puck light — Attley and Avery each received a treatment that suited their individual tastes. The kicker? Tasha added address numbers that feature the time each was born, just a minute apart: Avery at 2:57 and Attley at 2:58.

And so began a new adventure in renovating, which was not at all what they had in mind. When Tasha and her husband, Joe, decided to move to the country, they had hoped their new chapter would unfold in a new build. After all, they’d just spent eight years transforming their previous home. “I love renovating, but I was tired,” says Tasha. After bidding unsuccessfully on two newly constructed homes, the couple settled for an eight-year-old home on a quiet Oak Ridge street.

“It ticked every box and, so I thought, we can do the same thing,” says Tasha. “We’ll do it slowly.” In October of 2020, the Agrusos moved out of their contemporary Starmount Forest dwelling and began their journey creating a colorful country oasis for themselves and their 12-year-old twin daughters.

In just three years, Tasha and Joe, a firefighter, have made tremendous strides. Tasha documents the DIY projects and makeovers on her website, Kaleidoscope Living. Her skills have earned her an appearance on the Rachael Ray Show as well as features in several digital and print publications such as Better Homes & Gardens. Through her site (kaleidoscopeliving.com) and on instagram (@tasha.kaleidoscope), where she boasts a formidable fan base of over 100,000 followers, “I educate people about how to decorate their homes in a way that makes them happy,” she says.

And she should know. It’s something she’s perfected in the many years spent making over their new house as well as their former home, the one that she says “changed everything.” During their time spent living in Starmount Forest, her daughters grew from toddlerhood into tween-age; the couple honed their DIY skills; Tasha left her career as a lawyer to forge a path in the digital world through her website’s educational tools and print shop (read about that journey in our 2018 summer issue of Seasons: seasonsmagazinenc.com/designer-profile); and, finally, it “was the house where we finally really understood our style.” And that style? A blend of Joe’s more reserved approach, Tasha’s love of color and pattern, and functionality for all four.

Three years after selling it, Tasha still misses their Greensboro home fiercely. “If I could have lifted that home and moved it, I would have,” she muses. As for the current home, will she ever love it as much? If you’d asked her when they first bought it, “Absolutely not possible.” But now? “If I am here for eight years like I was there and we continue to slowly change everything that we want to change, yeah. I could even love it more.”

Location is the one aspect of a house that cannot be changed and the family knew what they needed. “We’re all just such homebodies.” While she’s sure homebodies can exist in bustling areas, she says there are those “who crave quiet and stillness. That’s the kind we are.”

In their current home, the couple has applied what they’ve learned, chipping away with project after project since moving over the last three years. The makeover that has had the biggest impact on Tasha? Probably not what you’d expect: the stairwell.

“People ask, ‘Why would you take out iron balusters and put in wood ones?’” Tasha says, then answers. “Because we didn’t like the other ones.”

Once the more traditional wooden balusters were put in place, she got to work painting the stair risers and bordering walls in Sherwin-Williams’ Refuge, and the balusters and handrails were coated in Seaworthy. But the crowning touch? “We could have made all the structural and paint color changes to the stairs and it wouldn’t be my favorite if it weren’t for the colorful stair runner,” says Tasha.

Now, the colorful random-rainbow stair runner, she says, “is like a dose of happy every time you walk up and down.” Used every day, visible from the entry, primary bedroom hallway and living room, it serves as the heart of the home.

And did Joe get a say? “I have always said we both have the power of veto,” says Tasha. In fact, it’s something they have resorted to from time to time. After all, she says, “we both live here.” Together, they’ll narrow down choices, eliminating those — such as a very bold, colorful, plaid stair runner — that take Joe beyond his comfort zone. “His little bit of restraint is probably one of the things that makes things not cross the line into too chaotic,” Tasha admits.

That yin and yang of their blended aesthetic is visibly at work in their primary bedroom. White walls pair with white furnishings and a gray upholstered bed, but color comes through in lush, green velvet textiles, and patterned and abstract art. The result? A serene yet far-from-boring sanctuary for a busy couple.

For Tasha, it was important that her daughters each have their own personal havens as well. Avery, a swimmer who favors neutrals like her father, sleeps in a cozy room blanketed in whites and warm woods. Small doses of earthy colors show up here and there in the holiday-green textiles, and artwork such as the Christmas village canvas on her wall, created by Tasha.

As for that canvas and many of the prints throughout her house, well, Tasha took a note from the Grinch, who could not find a reindeer and made one instead. “Sometimes when you can picture what you want and you know what the space needs, you can’t find it,” she says. So, she makes it. She has both painted with watercolors and created with graphics editing apps, first using Illustrator, but is excited to try her hand at Procreate with digital brushes she just ordered. “We’ll see how that journey goes,” she quips.

Attley, a dancer who craves bright colors like her mother, has the same Pure White paint by Sherwin-Williams on her walls, accented by a vibrant floral wallpaper in aqua, pink, green and golden yellow behind her bed. Her furniture is painted in saturated hues of coral, peony and mustard, all playing off the whimsical large-scale paper. And, of course, the artwork in her room was also designed by mom.

Just as Tasha teaches readers of her website to decorate in a way that makes them happy, she wanted her girls to get the memo.

“It just felt almost like a subliminal message to send to them: You’re your own people, you have your own identities, you have your own spaces and I love them both so much.”

That individualism spills out into the hallway where she created those apartment-style doors. And while the mailboxes are mostly a fun decorative detail at this point, Tasha anticipates using them in the upcoming teen years. With Attley and Avery turning 13 later this month, Tasha says, “We might be entering that phase of life where it’s hard for them to say things directly to us and vice versa,” she says. “Sometimes it’s easier just to communicate things in writing.”

Tasha sites these doorway makeovers as a prime example of what she believes. “The whole reason I chose the name Kaleidoscope Living . . . is because I have always believed and hope to have proven that you can take very ordinary objects and make them extraordinary.” It’s just like when you look through a kaleidoscope: “The most basic thing can become incredible.”

Just outside their doorways in the upstairs hall is a nod to both Joe and his father, a volunteer firefighter who passed away a few years ago. A vintage “Fire Dept.” sign that once belonged to Joe’s dad hangs above two antique fire extinguishers Tasha surprised Joe with several years ago. Until now, she says, they hadn’t found the right home.

Back on the main floor, the balance between Joe and Tasha’s aesthetics can be seen at play. In their living room, Tasha sits on a lush, comfortable sectional, her feet propped up on a warm leather ottoman. Behind her, a picture ledge featuring large-scale art, a patterned accent wall and textiles provide her favorite details. “I am always led by color and texture and pattern,” she says. Next to her, a stitched color-block pillow exemplifies those elements.

While selecting art used to intimidate Tasha, who felt herself unqualified, over time she learned to trust her instincts. “Finally, I realized I should probably just pick what I like,” she says.

Opening to the spacious living room, the kitchen serves as visual eye candy, featuring an island Tasha painted in the same vivid teal as its cabinets, Fusion mineral paint in Seaside. While the island is lined with four large and comfortable leather-woven counter stools, the family still opts to use their dining room regularly. “I just have a pet peeve of rooms not being used, so we don’t treat our dining room like it’s precious or special,” says Tasha.

Her years of learning to do what she loves have led to what she’s sure will be a highly controversial dining room decision. “By God, we’re putting a TV in there!” she says. These days with the juggling of their active kids’ schedules, Tasha and Joe eat dinner with Attley most nights while keeping Avery’s warm for her return, which generally coincides with when the family sits down to watch a show together. Current stream? Modern Family.

While a TV in a dining room is far from conventional, so is this modern family. Tasha leans into what works for them. “I know a lot of people have what you would call a traditional Christmas meal that looks a lot like Thanksgiving would look,” she says. But the Agrusos? They keep it simple with a Christmas meal of spaghetti and meatballs, a nod to Joe’s Italian heritage.

Because Joe works as a firefighter, there are times when he can’t be home for the holidays. Another unique Agruso family tradition? Tasha and the girls bake “something yummy” to bring to the station. “That’s a weird part of our tradition, but it’s part of our reality.”

One thing they always make time to do together is decorate the Christmas tree, usually before Thanksgiving so that they can enjoy its glow for a longer time. When it comes to decorating for the holidays, Tasha follows her heart, staying true to what she loves, “which is probably why I have things that I bought 20 years ago that I still love.” Avocado-green and dusty-red ornaments — nontraditional traditionals — purchased from Crate & Barrel during Tasha and Joe’s first Christmas together still, to this day, adorn their tree and fit the existing aesthetic.

After all, when you decorate by choosing what you really love, you’re sure to be happy with the outcome. “It’s like what bra and underwear you pick. Is it comfortable to you?” asks Tasha as she takes in the home she’s been personalizing for the last three years. She laughs and adds, “I have literally never thought of the undergarment analogy, but it’s actually a really good one.” OH

ADVERTISE

Tag Archives: 2023

Burlington Industries Celebrates a Centennial (1923–2023)

Burlington Industries Celebrates a Centennial (1923–2023)

Tag Archives: 2023

Following the thread of a financial genius

By Ross Howell Jr.

Featured Photo: J. Spencer Love (1896-1962) parlayed used equipment from his grandfather’s cotton mill into the largest textile manufacturing company in the world.

Workers commenced production at Burlington Mills Corp. in 1924, before construction of the building was even finished. Only half of the weave room had a floor, while the rest was earthen. Entrepreneur J. Spencer Love had chartered the company on November 6, 1923, naming it in tribute to the town where it would be located. The plant in Burlington would eventually employ some 200 workers.

Burlington Mills first produced all-cotton textiles, including flag cloth, bunting, curtain and dress fabrics, plus diaper cloth. But sales of cotton goods were declining. Spencer Love decided to experiment with a fiber called rayon — relatively unknown to American households. Rayon is made from purified cellulose, harvested primarily from wood pulp, which is then chemically converted. Right out of the gate, Burlington’s rayon bedspreads were a runaway success, facilitated by Love’s commitment to a world-class truck fleet for delivering products.

In 1935, Love (standing under the portico, wearing a light-colored overcoat) decided to move the company from its Burlington headquarters to Greensboro — primarily to take advantage of better rail transportation to New York City, where the company had opened a sales office in 1929, the year of the stock market crash. As America sank into the Great Depression, Burlington Mills kept growing, buying and reopening many of its competitors’ shuttered mills. Love’s strategy of growth through acquisition continued after the Depression and made the company an industry giant. Fred Rogers, Friendly Acres, remembers: “For a decade starting about 1990, I worked in the Burlington House division of Burlington Industries. That division had offices at 1345 Avenue of the Americas in New York City and in the town of Burlington, just down the street from the pioneer plant, where Spencer Love had built his first mill in a cornfield. A lot of people think of Love as a manufacturing man, but he was, in fact, a financial man. I’d say he was one of the earliest and best financiers in America, because he grew his company by acquisition. He was a financial genius.”

Men in skivvies? Burlington operations took a sharp turn in 1941, when the U.S. entered World War II. Burlington shifted to wartime production of more than 50 products for the armed forces, while the company’s research laboratories developed parachute cloth woven with a new fiber — nylon, a thermoplastic usually made from petroleum. Postwar, Burlington developed an array of clothing and home goods. Magazine ads featuring GIs gave way to TV ads with a “dancing man” wearing Burlington socks or stars such as singer Petula Clark and actor Robert Morley as spokespersons for the brand — along with a new corporate name, Burlington Industries.

Founder J. Spencer Love directed bold innovations during his nearly 40 years as president, but died unexpectedly at the age of 65 in 1962, the year Burlington Industries surpassed $1 billion in annual sales and became the first textile company in history to achieve that goal. In the 1960s, Burlington was the parent corporation for 17 constituent companies comprising more than 100 plants that manufactured products ranging from ribbon and suit fabrics to hosiery and carpets.

Retired schoolteacher Jane Gallimore, Fisher Park, remembers: “My family was living upstairs in the funeral home in Burlington my father owned. I was 10 years old. We’d driven over to Kirkwood to visit my aunt. Spencer Love’s death was in all the newspapers and my aunt suggested we drive by the house, just to see what was going on. I remember the house being on Sunset Drive. It had a circular driveway and we watched cars enter, dropping people off. I remember seeing butlers wearing white coats and white gloves meeting the cars and escorting guests inside. That sight has stayed with me all these years.”

In 1971, Burlington Industries built a new headquarters in Greensboro. The six-story structure featured an award-winning architectural design and was located on an expansive campus on Friendly Avenue. Its massive, crisscrossing steel trusses were said to represent the warp and weft of the fabric that created Burlington Industries’ great wealth. But for many people, they were a huge eyesore. The building was demolished in 2005 to make way for Friendly Center Shopping Center. Delores Sides, Summerfield, remembers: “Twenty-nine years ago I began work at Burlington Industries in the Rockingham plant. During the boom years, the company built a modern, glass-and-steel headquarters on Friendly Avenue. The structure won architectural awards, though everyone seemed to have an opinion about it, not always favorable. When the building was imploded in 2005, we watched from our new headquarters on Green Valley Road. We could glimpse the top of the building from our windows. There was a vibration, and then the top of the building was gone. It was the end of an era.”

After expending $2 billion over a 10-year period on a modernization initiative in the 1970s, Burlington Industries fended off a hostile takeover attempt in 1987 with a leveraged buyout, but was forced to file for Chapter 11 reorganization bankruptcy protection in 2001. While diminished from its heyday, Burlington Industries has been recapitalized and now manufactures high-tech fabrics at facilities in the Southeastern U.S., Mexico and China. Its offices were recently moved from Green Valley Road to — fittingly enough — beautiful, renovated facilities at Revolution Mill. OH

Freelance writer Ross Howell Jr. is grateful to Elevate Textiles, Inc., for its help with this article. For more information on Burlington Industries, visit www.elevatetextiles.com. On YouTube, you can find examples of vintage Burlington Industries TV ads, including the dancing man.

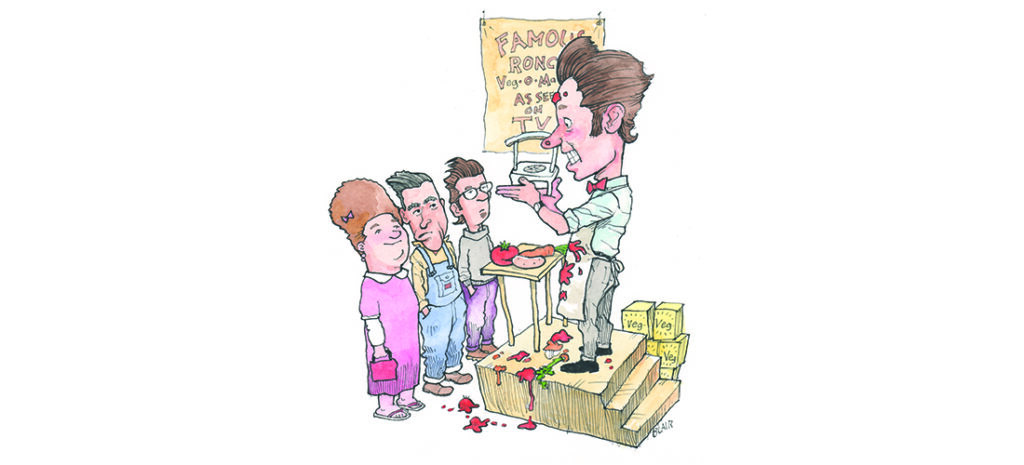

It Slices. It Dices.

It Slices. It Dices.

Tag Archives: 2023

“Get up! Get up! Get up, up, up!” my mother blurted.

It was at 6:30 a.m., the first day of Christmas break, and as always she felt compelled to rouse her children at the most ungodly hour. I lifted my head from the pillow and stared bleary-eyed at her figure in the bedroom doorway. Wrapped to her chin in a blue terrycloth robe, her fists were planted firmly on her hips. She meant business. “You’re to march yourself down to the Safeway and ask Mr. Short if he’ll give you a job for the holidays,” she ordered. “You can earn enough money to pay for your books next semester. And next time I see Mr. Short, I’ll find out if you asked him for a job.”

“Can’t you even say, ‘Welcome home’?” I asked.

“Sure. Welcome home, Mr. Big Shot College Guy. Now get out of that bed and get yourself down to the Safeway.”

I was suffering from severe sleep deprivation. I’d caught an all-night ride home from North Carolina and had dragged into the house on Janice Drive at 3:15 a.m. But my mother was not to be denied, so I managed to pull on the wrinkled clothes I’d worn the day before and stumbled downstairs to eat a bowl of my brother’s Froot Loops. At 8:30 a.m. I scuffled up Bayridge Avenue to the Eastport Shopping Center, where I found Mr. Short on the dock, supervising the unloading of pallets of dog food from a tractor-trailer. He shook my hand and asked how college was going.

“It’s fine,” I answered. “I was hoping you might have an opening for a cashier during the holidays. I’m not looking to work eight hours a day, but, you know, something part time.”

“If I had an opening, I’d hire you,” he said. “But right now I have all the cashiers I need. I’d have to cut someone else’s hours, and that wouldn’t be fair, especially at Christmas.” My spirits soared. If he didn’t have an opening, I could pass the holidays stretched out on my bed reading P.G. Wodehouse.

“I’ll tell you what,” he continued, “I’ve got a friend who’s the manager at the Drug Fair in Parole. Go see him and tell him I sent you. He’s looking for holiday help.”

A job at Drug Fair was the last thing I wanted, but I had to make an inquiry. My mother was as good as her word, and I knew she’d buttonhole Mr. Short the next time she visited the Safeway. If she found out I hadn’t applied for the Drug Fair job, she’d make my Christmas break miserable, which she had already begun to do by wakening me before sunup.

Among cashiers, there existed a hierarchy, and working a register at Safeway carried with it a degree of status and a wage that was at least $1.75 an hour. Drug Fair was a discount pharmacy, emporium and grocery store, a low-rent warehouse for plastic crap and wilted vegetables, where the discount prices were clearly marked on each item — work for the dimwitted — and the pay was $1.25 an hour.

I caught the bus to Parole and found the Drug Fair manager, a rumpled, balding, ectomorphic fellow with thick wire spectacles and a long pointy nose, puzzling over paperwork in an elevated office that overlooked a line of disheveled employees who were pounding away at their cash registers. He appeared to be in emotional distress, his mouth screwed into a grotesque snarl.

“Excuse me,” I said. He looked up, snatched the glasses from his face and tossed them on the countertop in a display of frustration. “Mr. Short over at Safeway said I should talk with you about working as a cashier for the holidays. I don’t need a full-time job, just some part-time work if you’ve got it.”

Sweet relief swept over his face, his lips stretching into a half smile. “Mr. Short sent you?” he asked.

“He said you might need an experienced cashier.”

“You used to work at the Safeway?”

“For two years, until I went off to college.”

He grinned fully. I was apparently the man he’d been waiting for. He stepped out of his office, planted both feet flat on the linoleum and looked me up and down. “Can you work a register?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“And you’ve worked stock?”

“Yes, sir.”

My God, he was going to hire me! I was going to pass the next two weeks checking out Christmas junk at the Drug Fair for minimum wage! This was not good.

The manager handed me a pen and an application clamped to a clipboard, and I took a couple of minutes to fill in the information.

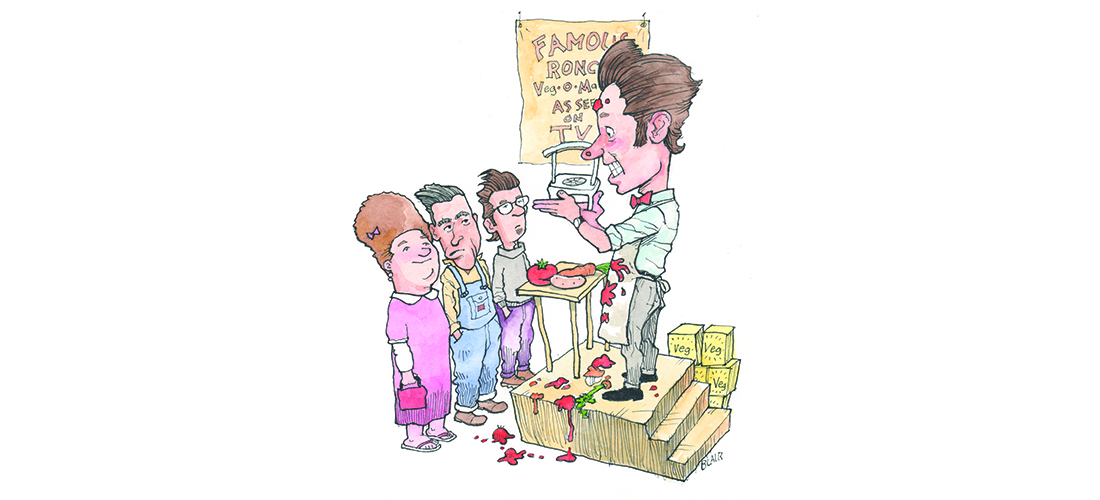

“Follow me,” he said, and we walked quickly down aisle four toward the back of the crowded store. “I can use you to relieve my regular cashiers for their lunch and supper breaks, and you can help keep the shelves stocked, especially this display. We’re selling the hell out of these things.” He pointed to a chest-high pyramid of black, orange and beige boxes crowned with an unboxed white plastic kitchen device known to every American who owned a TV. “We’ve had to restock this display three times this morning. You know anything about Veg-O-Matics?” he asked.

What happened next was probably brought on by fatigue — or maybe I needed an excuse to get fired before I got hired. Whatever the cause, a synaptic misfire propelled me into the past. I picked up the display device, held it out in front of me and began to deliver the requisite spiel:

“Imagine slicing a whole potato into uniform slices with one motion. Bulk cheese costs less. Look how easy Veg-O-Matic makes many slices at once. Imagine slicing all these radishes in seconds. This is the only appliance in the world that slices whole firm tomatoes in one stroke with every seed in place. Hamburger lovers, feed whole onions into Veg-O-Matic and make these tempting thin slices. Simply turn the dial and change from thin to thick slices. You can slice a whole can of prepared meat at one time. Isn’t that amazing? Like magic, change from slicing to dicing. That’s right, it slices, it dices, it juliennes, perfect every time!”

By the time I’d finished yammering, the manager’s eyes were wide and his jaw slack.

“How’d you learn that?” he asked.

“I used to watch the commercial on TV, and it just sort of stuck in my head.”

My fascination with the Veg-O-Matic stretched back to my junior year in high school. Strung out on testosterone and teenage angst, I suffered insomnia for about six months. On those long, restless nights, I’d roll out of bed after everyone else in the house was asleep, slink down to the “rec” room and turn on the black-and-white TV. WJZ, the local CBS affiliate, was the only station out of Baltimore that aired anything other than an Indian Chief test pattern in the early a.m., so I’d tune in channel 13 in time to catch Father Callahan of St. Francis Xavier House of Prayer bestowing his benediction. Then I’d settle in for a three-hour run of continuous raise-your-own-chinchillas commercials.

My clandestine obsession with Father Callahan and chinchillas continued for two or three months — until the fateful night when the good Father delivered his usual homily and the chinchilla commercials failed to materialize. Instead, a plastic guillotine-like device appeared on the TV screen, contrasted against a background map of the world, below which were printed the words “World Famous Veg-O-Matic.” Then a disembodied voice said: “Imagine slicing a whole potato into uniform slices with one motion. Bulk cheese costs less. Look how easy Veg-O-Matic makes many slices at once. . . . ”

I’d spent my Father Callahan/chinchilla nights dozing fitfully on the couch and sneaking back to my room before the rest of the family awakened, but on that memorable evening — I’ve come to think of it as Night of the Veg-O-Matic — I sat there stupefied, watching the commercial over and over. I couldn’t take my eyes off the screen, and by morning I had the narration memorized — every nuance, modulation and inflection — to which I could add hand gestures, including the graceful, upturned palm that beckoned, “Buy me, buy me, buy me. . . .”

Later that day, I was eating lunch in the high school cafeteria with my regular buds when freckle-faced Ronnie Wheeler produced a sliced tomato his mother had wrapped in wax paper to keep it from saturating the white bread he needed to construct his BLT. I jumped up, grabbed the tomato slices and ran through the entire Veg-O-Matic routine, spreading the segments across the Formica tabletop and finishing with the obligatory “. . . perfect every time!”

My friends were speechless, especially Ronnie, whose sandwich was ruined. They stared blankly before bursting into hysterics. The vice-principal, Mr. Wetherhold, a stern disciplinarian who abhorred any form of frivolity, hurried over to our table to discern the source of the disturbance. “What’s going on here?” he asked sternly.

“Do it!” my friends begged. “Do the Veg-O-Matic thing!” They didn’t have to ask twice. When I finished my second run-through, it was Mr. Wetherhold who was howling with laughter. Suffice it to say I spent a good deal of my time in high school doing “the Veg-O-Matic thing” for my friends. They never tired of it.

Now the Drug Fair manager’s face glowed with approval, and I could see that he’d suffered an epiphany. He rushed into the stockroom and reappeared with a folding table. He extended the legs, positioned the table in front of the pyramid of boxes and covered the top with a square of red cheesecloth. He grabbed an onion from the produce aisle, peeled away the skin, and ordered me to deliver my recitation again, this time with the unboxed Veg-O-Matic at my fingertips.

Despite my long and intimate history with the kitchen device, this was the first time I’d worked with one. But I muddled through the presentation by recalling the images I’d watched hundreds of times on TV, each motion transmitted from memory to physical articulation. I made quick work of the onion, repeating the entire monologue. My demonstration, although clumsy, went well enough to instantly earn me the title: 1965 Parole Drug Fair Veg-O-Matic Man.

“You’re hired!” the manager said. “I want you to do a demonstration at the top of every hour. Use all the tomatoes and onions you want, but stay away from the cheese and Spam. That stuff costs money.”

“Yes, sir,” I said dutifully.

“The rest of the time you can restock these Veg-O-Matics and relieve the cashiers who are going on break. Can you start tomorrow?”

“Yeah,” I said, “I guess.”

“Be here at 8 o’clock, and wear a white shirt.”

Crestfallen, I dragged myself into the parking lot and caught the bus back to Eastport. When I stumbled into our living room, it was 11:30 a.m., and I was whipped.

“Did Mr. Short hire you?” my mother yelled from the kitchen.

“He didn’t have any openings, but I got a job at Drug Fair in Parole.”

“Excellent,” she said.

When I turned up at Drug Fair on Saturday morning ready to begin my new career, the manager had anticipated my every need. The folding table was set up in aisle four, which was stocked with kitchen junk — Melmac dishes, spatulas, plastic forks, spoons and knives, etc. — and beside the table waited a freshly replenished pyramid of multicolored boxes containing the Veg-O-Matics. The tabletop was covered with the red cheesecloth from the day before, and a white apron of the style that loops around the neck and ties in the back was folded neatly on the table. An unopened can of Spam and a brick of Kraft Velveeta cheese were stacked beside the gleaming white Veg-O-Matic display model I’d used in my earlier demonstration, and a bag of assorted vegetables — tomatoes, onions, carrots and potatoes — awaited their fate. As a touch of class, the manager had placed a roll of paper towels on the table, and a beige commercial dome-topped trash can sat directly behind my workspace.

“Here, wear this,” he said, handing me a handsome black clip-on bowtie. I donned my apron and attached the bowtie to the wrinkled collar of my white shirt. “Now show me your stuff. Just use vegetables. The Spam and cheese are for show.”

I launched into my Veg-O-Matic dance at a measured pace, slicing up a small potato and allowing my hands to gracefully execute a lilting swirl at the conclusion of the shtick.

“That was even better than yesterday,” the manager beamed, “although I’d take it a little slower if I were you.” He looked up and down aisle four. “I’ll make an announcement at the top of every hour. You get yourself set up. Sell the hell out of these Veg-O-Matics. If you don’t, you’ll be in a checkout stand all day.” And he left me on my own.

I peeled an onion, and trimmed it to the proper size and shape. I was ready. Or as ready as I was ever going to be.

“We are pleased to direct your attention to aisle four,” I heard the manager announce over the PA system, “where you can view a demonstration of the miracle Veg-O-Matic, the 20th century’s greatest kitchen appliance. It makes an economical and useful Christmas gift! Do all your Christmas shopping in five minutes and have your Veg-O-Matics gift wrapped right here in the store. Christmas cards are available on aisle six.”

After my first two demonstrations, I discovered that operating the Veg-O-Matic wasn’t quite the effortless exercise I’d observed on TV. I directed my attention to the tomato, which I positioned perfectly between the upper and lower blades. “This is the only appliance in the world that slices whole firm tomatoes in one stroke with every seed in place,” I said, as I slammed down the top of the Veg-O-Matic. The tomato exploded like a water balloon, splattering juice and seeds all over my apron and the tabletop. The two customers who had gathered for my demonstration jumped back and bolted for the exit.

I’d created a huge mess. I mopped the tomato slop off my hands with a paper towel and brushed the seeds from my apron, but pulp continued to dribble from the bottom of the Veg-O-Matic, and I had to retreat to the stockroom to wash the blades. So tomatoes were out. Ripe ones, at least. After mopping the splatter from the tabletop, I attempted to slice an onion I’d peeled earlier. I gave a forceful downward thrust and the device worked perfectly, sending a cascade of onion slivers onto the cheesecloth. Still, it was a messy business; pieces of onion got stuck in the blades and had to be pried out. I had the same experience with carrots, stubborn chunks of which had to be worked free with my fingertips.

I settled, finally, on a peeled Idaho Russet potato. I cut the spud into four pieces, which I fed individually into the chopper. And the device worked as intended — neat and clean. The Veg-O-Matic was, after all, meant to transform a time-consuming, chaotic operation into a simple, wholesome procedure. And that’s what it did.

The secret, as with many physical actions, was in the wrist. It was all finesse. I’d place a piece of potato on the bottom blades and apply a sharp downward whack with the top. And voila! the potato was julienned, perfect for hash browns. If I spoke slowly, worked methodically and was meticulous with my cleanup, I could kill the better part of a half hour on each demonstration, thus allowing for only 30 minutes of working at a cash register before my next demonstration.

At first, I was worried that I wouldn’t sell enough Veg-O-Matics to keep my new job, but the pile of boxes diminished at an ever-increasing rate as Christmas approached and the manager was a happy man. I’d sold six to eight Veg-O-Matics with each demonstration, and I noticed that many customers who didn’t make an immediate purchase returned later to snatch up two or three Veg-O-Matics, having chosen convenience over thoughtful reflection. Usually these return customers felt compelled to offer an explanation for their delayed purchase. “You know,” they’d say, “I was thinking about your demonstration, and you’re right, this will make an excellent gift for my mother.”

Every day I’d work straight through until 10 p.m., taking an hour each for lunch and dinner, and then I’d catch the bus home in the dark. I’d shower and collapse into my bed to read for a few seconds in Pigs Have Wings, my latest Wodehouse novel, before falling asleep.

And that’s how it went for seven straight days. I’d turn up at Drug Fair at 8 a.m., an hour before the store opened, to prepare the potatoes for my demonstration. I’d restock the Veg-O-Matic display, piling the boxes high in an ergonomically conical construct of my own contrivance, and check out a register tray so that I could relieve cashiers who went on break.

If my schedule was exhausting, it also had its advantages. I slept like a stone, and the days flew by. At home, I didn’t have a conversation with my mother, father or sister that lasted more than 10 seconds. “Hi, how ya doing?” was as intimate as it got, which suited me. My father was asleep when I left in the morning and when I came in at night, I didn’t have to listen to my mother and sister bicker. Only my brother Mike, with whom I shared a room, was around when I staggered in whacked out from 12 hours of working with the public. He’d fill me in on the day’s drama with my sister, which made me glad I’d be headed back to college soon.

When the store closed at 9 p.m. on Christmas Eve, I used my humongous 5 percent employee discount to purchase gifts for the family — a cheap cotton bathrobe for my mother, which turned out to fit her like a circus tent, a simulated leather wallet for my father, a 45 of Donovan’s “Catch the Wind” for my brother, and the Beatles’ Help! for my sister. I was headed out the door with my packages when the manager stopped me.

“You’ve done a good job,” he said, a genuine smile on his pasty face. “And I’m hoping you’ll consider coming back to work through New Year’s Eve. You won’t be selling Veg-O-Matics, but I need experienced help to run the registers and handle returns. I could use you for at least 12 hours a day.”

Normally I would have responded with an emphatic “No,” but fresh in my memory were the money problems I’d experienced during my first four months at college and the hours I spent in McEwen Dining Hall scraping greasy dishes and scrubbing pots. With my paltry allowance, there was no hope of establishing a relationship with any of the girls I found myself drooling over as they roamed the campus. It was essential I screw up my courage and get myself an on-campus date. I’d have to double with an upperclassman who had a car, and to make that happen, I needed enough money to cover my share of the gas.

“All right,” I answered. “Can I get some overtime?”

“I’ll give you all the overtime you want. You can work 14 hours a day if you skip lunch and dinner.”

“All right,” I answered, “I’ll be glad to help out.”

So on December 27, I was standing behind a cash register refunding money for the Veg-O-Matics I’d sold the week before. “I’d like to get the money back for this thing,” the customer would say, handing me the orange and black box. They occasionally offered excuses such as “I already have one of these” or “I have no use for this piece of junk,” but what they wanted was cash. In almost every case the customer returning the Veg-O-Matic was not the person who’d bought it, so I didn’t consider the returns a criticism of my performance. I handed them the money and stuck the boxes and signed receipts under the register. At the end of the day, I toted the returned Veg-O-Matics to the storeroom and piled them up in the same space they’d occupied when they were new.

To compound this irony, the manager handed me a hammer at closing time on my first post-Christmas day as a cashier and sent me to the stockroom to smash the Veg-O-Matics the store had taken back. “Just bash those veggie things into little bits and put them back in the boxes,” he directed. “And while you’re at it, smash up these toys that didn’t get sold.” The manager didn’t explain why I needed to destroy so much perfectly good merchandise, and I didn’t ask. But I laid into my new task with gusto, obliterating hundreds of Veg-O-Matics along with Chatty Cathy dolls, Etch-A-Sketches, tin airliners, space guns, trains, battery-powered James Bond Aston Martin cars, Rock ’em Sock ’em Robots, Easy-Bake Ovens, electric football games, G.I. Joes, and the occasional Barbie doll, perfectly good toys that might have gone to poor children who’d suffered a sad Christmas. But it was exhilarating work — and strangely gratifying — an anti-capitalistic binge that assuaged the guilt I’d suffered from selling plastic crap to poor people.

But the days were long, and there was no time to hang out with my friends. When I got off work at 9 p.m., I was too worn out to go to parties or ride around with high school buds. I’d catch the bus back to Eastport and fall into bed. The following morning, I’d get up and do it again.

On my last day of work, a Friday, the manager shook my hand. “You’re a lifesaver,” he said, pumping my weary arm. “If you need a job next Christmas, just let me know.”

I smiled, gave him my college post office box number and asked him to send my check there rather than to my home address.

“You should get it before the 10th,” he said.

During the two-and-a-half weeks I’d toiled at Drug Fair, my parents hardly noticed my absence. I was a shadow who flitted in and out at odd hours. And I wanted it that way. I didn’t have to listen to them argue, which was their habitual method of communication during any holiday season when they were forced to remain in each other’s company for more than five continuous minutes. And if my parents didn’t realize the hours I was working, they’d have no idea how much money I was making. Had they an inkling of the cash I was likely to pocket, they would have given me that much less for tuition, room and board, and the endless hours I’d spent slaving at Drug Fair would have been for naught.

On the evening before my return to Elon, in honor of my having been invisible during the holiday season, my mother prepared lasagna, my favorite dish.

“You headed back tomorrow?” my father asked.

“First thing in the morning,” I answered, “I’m going to catch the bus.”

My mother looked puzzled. “It seems like you just got here,” she said.

“I’ve been working the whole time.”

“Good,” she said. “How much money did you make?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t gotten paid yet — and the wage at Drug Fair isn’t as much as it is at the Safeway. I’ll let you know when the check arrives.” I was lying, of course. I had no intention of telling anyone how much money I’d earned. It was nobody’s business but mine. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of eight books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards. This is an excerpt from his forthcoming book The Year We Danced: A Memoir.

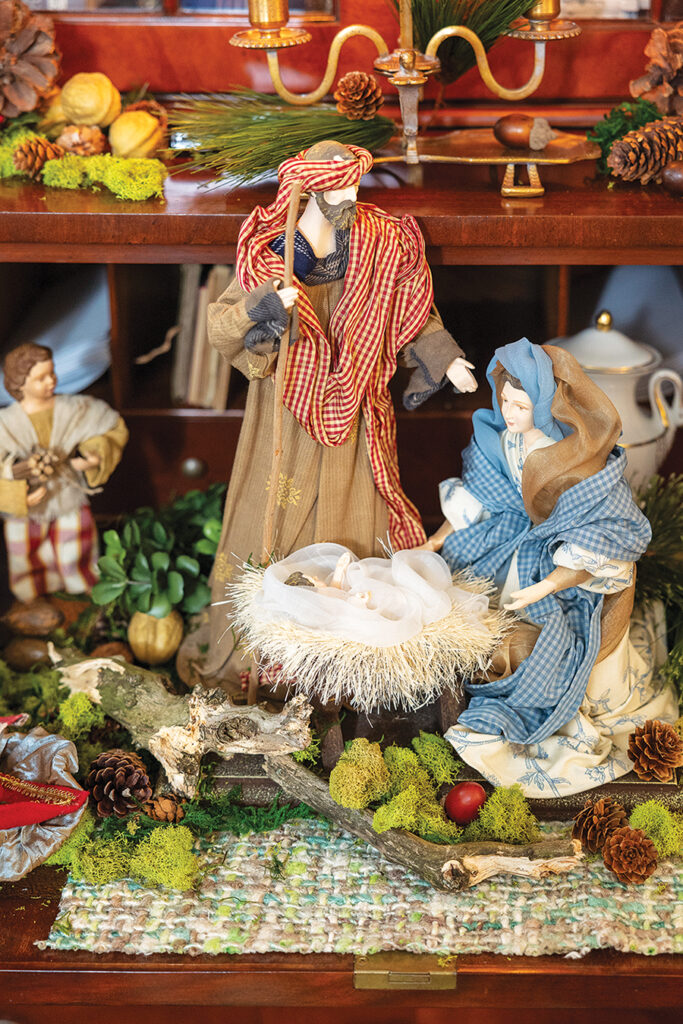

A Fresh Take on Faux for the Holidays

A Fresh Take on Faux for the Holidays

Tag Archives: 2023

Elevating favorite collections with greens

By Cynthia Adams

Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

Pre-holiday, Sharon James invited Todd Nabors to give her Whitsett home his signature faux-mixed-with-fresh ideas a go. Nabors, a long-time friend, consults on occasion with avid collectors — like James — seeking to elevate their favorite things. For Nabors, Mother Nature lends all the inspiration needed.

He favors natural touches like running cedar and garden greenery, even on gift wrapping.

Though she admired how Nabors relied upon natural elements, James had a quandary. During work absences, evergreen embellishments simply wouldn’t last.

Nabors had a solution. It’s perfectly fine to cheat a little, tucking faux greenery in with fresh.

“Consider where greenery and color are needed, and invest in the best faux foliage and blooms for your seasonal decorating budget,” Nabors advises. “Remember that, while realistic garlands, wreaths, trees, fruit and blooms are expensive, they last for many seasons.”

Plus, “these ‘almost real’ elements facilitate decoration schedules early or late in the season. They require no refreshing, replacement or clean up.”

Nabors favors a realistic, classic mix, using “faux spruce, pine, magnolia with forced amaryllis, narcissus and Christmas roses [hellebores].” For more oomph, place faux cyclamen and orchids in a fool-the-eye container, such as “a crusty terra-cotta pot, tole or porcelain cache pot, or woven basket.” Faux Osage oranges, lemons, kumquats, pears and figs “beautify holiday garlands, wreaths and bowls.”

Fresh or faux, James and Nabors go all out. Yet, simplicity is lovely, too. An orchid nestled inside a beautiful wreath may be all that a holiday table requires, Nabors insists.

The Moravian star, a touching reminder of the Moravians’ long presence here in the Triad, was purchased at the Moravian Book & Gift Shop in Old Salem store (Although it closed earlier this year, it can still be shopped online). The wreath features various faux citrus styled by Nabors.

Covered boxes in marbleized paper (turquoise and jade) are tied with brown and orange satin ribbon. The faux cinnamon studded oranges were found at Randy McManus Designs in Greensboro.Covered boxes in marbleized paper (turquoise and jade) are tied with brown and orange satin ribbon. The faux cinnamon studded oranges were found at Randy McManus Designs in Greensboro.

Don’t forget the importance of a good entrance. Even a pair of antique stone balls from the English Cotswold are decorated for the holidays.

The stone fire pit overlooks the Stoney Creek golf course, where even a tall ornamental urn (one of a pair) is decorated with traditional greenery and ribbon.

A simple Christmas nutcracker and crèche figures provide another festive touch in a house overflowing with holiday spirit.

A treasured crèche is displayed with a white reindeer and an antique knife urn. “The little figures are from Lima, Peru,” says James. “The deer is from Gump’s catalog. And the feathers are actually little white owls made of feathers. Todd and I placed my collection of feathered owls all throughout the house.”

James has collected crèches since the late 1990s. “All the fabrics on the figures are traditional French fabrics,” and the figures were ordered from a defunct French catalog.

Among the tree ornaments are French papier mâché rabbits that James has owned for 30 years. Others are from travels in the Philippines. The blue-and-white chinoiserie porcelain ornaments were found on Etsy.

A 19th century French jardinière containing the tree is from White Hall in Chapel Hill.

The 15th century icon (made of metal) is the saint for metal workers.

A holiday-ready tableau — tray of fruit, paper whites with a faux bird, and pierced compote dishes — is decorated with evergreen balls. A spray of greenery and citrus dress up antique knife boxes. Feathers embellish an 1860 Louis Phillipe mirror flanked by buffet lights from Plants & Answers.

Dig in! Spiced sweet potato cake is served on a Mottahedeh reproduction plate, with an antique mother-of-pearl dessert fork.

Spiced Sweet Potato Cake with Brown Sugar Icing

Cake

4 8-ounce red-skinned sweet potatoes (yams)

Nonstick vegetable oil spray

2 3/4 cups all-purpose flour

2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1 1/4 teaspoons ground ginger

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

2 cups sugar

1 cup vegetable oil

4 large eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Icing

1 cup powdered sugar

3/4 cup (packed) dark brown sugar

1/2 cup whipping cream

1/4 cup (1/2 stick) unsalted butter

1/4 teaspoon vanilla extract

Pierce sweet potatoes with fork. Microwave on high until very tender, about 8 minutes per side. Cool, peel and mash sweet potatoes.

Pierce sweet potatoes with fork. Microwave on high until very tender, about 8 minutes per side. Cool, peel and mash sweet potatoes.

Position rack in center of oven; preheat to 325° F. Spray 12-cup Bundt pan with nonstick spray, then generously butter pan. Sift flour, cinnamon, ginger, baking powder, baking soda and salt into medium bowl. Measure enough mashed sweet potatoes to equal 2 cups. Transfer to large bowl. Add sugar and oil to sweet potatoes; using electric mixer, beat until smooth. Add eggs 2 at a time, beating well after each addition. Add flour mixture; beat just until blended. Beat in vanilla. Transfer batter to prepared pan. Bake cake until tester inserted near center comes out clean, about 1 hour 5 minutes. Cool cake in pan on rack 15 minutes. Using small knife, cut around sides of pan and center tube to loosen cake. Turn out onto rack; cool completely.

Sift powdered sugar into medium bowl. Stir brown sugar, whipping cream and butter in medium saucepan over medium-low heat until butter melts and sugar dissolves. Increase heat to medium-high and bring to boil. Boil 3 minutes, occasionally stirring and swirling pan. Remove from heat and stir in vanilla. Pour brown sugar mixture over powdered sugar. Whisk icing until smooth and lightened in color, about 1 minute. Cool icing until lukewarm and icing falls in heavy ribbon from spoon, whisking often, about 15 minutes. Spoon icing thickly over top of cake, allowing icing to drip down sides of cake. Let stand until icing is firm, at least 1 hour. (Can be prepared 1 day ahead. Cover with cake dome and let stand at room temperature.)

Source: Epicurious.com

Poem December 2023

Poem December 2023

Tag Archives: 2023

Snowbird

The Latin teacher finally did retire. Her balcony now bends toward the sea. She is in a high-rise looking down at birds. Gulls scream and fly north to the next resort. All that’s left now are pigeons on the patio. They scavenge through the purpling decorative cabbage. She hasn’t seen a pelican yet, just the same birds she came here to get away from. They look like feathered cataracts in a kale eyeball. She sees a buried Titan with umbrella pectorals. It struggles to emerge from beneath the sodden November sand, beaten down by so many tenacious dog walkers. He has his eye on her.

— Maura Way

Maura Way’s second collection of poetry, Mummery, was published by Press 53.

Home Grown

Home Grown

Tag Archives: 2023

Confessions of a Biscuit Eater

A hair-raising adventure with Mama

By Cynthia Adams

My Mama sprang immediately to mind as a friend described a Triad maven he met while doing work for designer Otto Zenke. “She was always dressed bridge-ready. And she was so rich she had a hairdresser do her hair daily!”

Hairdressers everywhere should observe November 5 — the day she died — National Hair Day, versus October 1. (As hair care company NuMe declared in 2017, according to my editor.)

No matter the fluctuating fortunes, calamities or dramadies within our family, a few things were certain: The sun would rise right alongside a pan of Mama’s biscuits, and so would her closer-to-God hair.

Thy will and Mama’s hair would be done. Weekly. (Southerners know what “done” means . . . and in this case, it has nothing to do with biscuits.)

Her biscuit making, however, was instinctual after years of practice. Mama practically made them in her sleep, wearing a negligee, satin mules and a cocktail ring, which grew lumpy with dough as she kneaded. She slapped the pan in the oven, sipping a cup of black coffee before cracking eggs as the grits burbled on the stove.

Every day.

I lost my appetite for those pillows of Crisco, flour and milk in my early youth after learning from my new friend, Rocky, that toast was much cooler up north.

Rocky also touted frozen pies — anathema to my kin. When Judy, the daughter of our (adored) bookmobile driver, echoed Rocky’s preferences, I swore off biscuits, too.

Mama was fit to be tied when my 11-year-old self requested toast following our no-biscuit pact.

When Rocky moved away, I ate my words and rejoined the legion of biscuit eaters.

Mama’s passion for biscuits eventually waned, but hairdos were sacrosanct.

Her salon was called “Barbara’s.” Envision the salon in Steel Magnolias — except Barbara’s was actually at Barbara’s house. It was obvious when Barbara was working because the carport sheltered her patrons’ land yachts — Lincolns, Cadillacs and Oldsmobiles.

For hair to be considered truly “done,” it had to be impervious to wind, rain or natural disaster — minus wildfires — while made highly flammable with a shellacking of hairspray. Once done, women marched out of Barbara’s with helmet-like coiffures, teased and steeled. Fortified.

When older, her children grown, Mama wanted more. By her 70s, her salon visits were a twice-a-week habit.

Then Mama left my dad, Barbara and Hell’s Half-Acre behind, establishing a tight-as-ticks bond with a hairdressing duo in Norwood, NC — which even involved trips together.

Mama achieved Nirvana vacationing with her hairdressers. (“Perry and Terry freshened my hair up every day when we were in Disney World!” she said blissfully.)

When she eventually remarried and moved to Greensboro, Mama struggled to find the level of style — teased high and hardened off — she demanded.

She tried salon after salon, eventually discovering Wayne. It became a happy pairing. When I needed to find her, I could go straight to his salon, spot her Lincoln outside and find Wayne spraying with zeal, a plastic shield at her face.

“He knows what my hair needs,” she would explain. “So many hairdressers do not.”

She also grasped what Jim, her husband, needed. Given his thing for blondes, Mama’s dark tresses grew steadily lighter.

After Jim’s death, she moved nearer to my older sister.

The hairdresser hunt was on once more.

This proved more stressful than my (pragmatic) sister anticipated. They cycled through scores of beauticians as Mama’s health declined. Now using a cane, and soon, a walker, she began having falls, yet determinedly kept appointments.

When Mama fell completely out of the Lincoln at the curb in front of her newest salon, the kindly hairdresser was recruited to visit her twice weekly.

This, too, grew challenging as Mama grew unable to stand at a basin long enough for shampooing.

Only in recent months of no bleaching had I discovered what her natural color actually was — still dark at the back though gray at the front. Shampooing Mama’s hair in the shower one day, I announced I’d “do” her hair.

Glancing at mine — merely blown dry — she raggedly exhaled.

“Well . . .” Her hands fluttered in surrender. Attempting to twine her gray hair around a curling iron, I burned both her neck and my hand, and cussed. Mama looked exasperated as I held a cold cloth to her neck.

And started laughing.

“I’m having trouble, but it’s all because of your cowlick,” I lied sweatily.

“You don’t know diddly squat about hair or curling irons. Get that hairspray,” she giggled, indicating a large can of Big Sexy Hair. I sprayed her recalcitrant curls till wet, shakily trying to coax them into Modestly Compliant Hair.

When I burned us both again, Mama retorted, “Well, you’re no Wayne! Just get me my lipstick.” Big Sexy Hair couldn’t save me.

She pursed her lips as I swiped them with red — her perennial favorite — and reached for blusher, dusting her porcelain-pale face before swiping her lashes with globs of mascara, lending a jolting Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane effect. Mama was unrecognizable.

With a very light squirt of her cologne — Angel — I hurriedly wheeled her away from the mirror.

“Mama, why don’t I follow up that success by making a pan of biscuits?”

“Huh! Good thing I’m wearing my Depends,” she retorted drily. We giggled together; Mom, tremulous but plucky. “We can work on the hair later,” she added, and my heart dropped to my kneecaps. OH

Cynthia Adam is a contributing editor to O.Henry magazine.

Omnivorous Reader

Omnivorous Reader

Tag Archives: 2023

Tales to Tell

The journey of a lifetime

By Anne Blythe

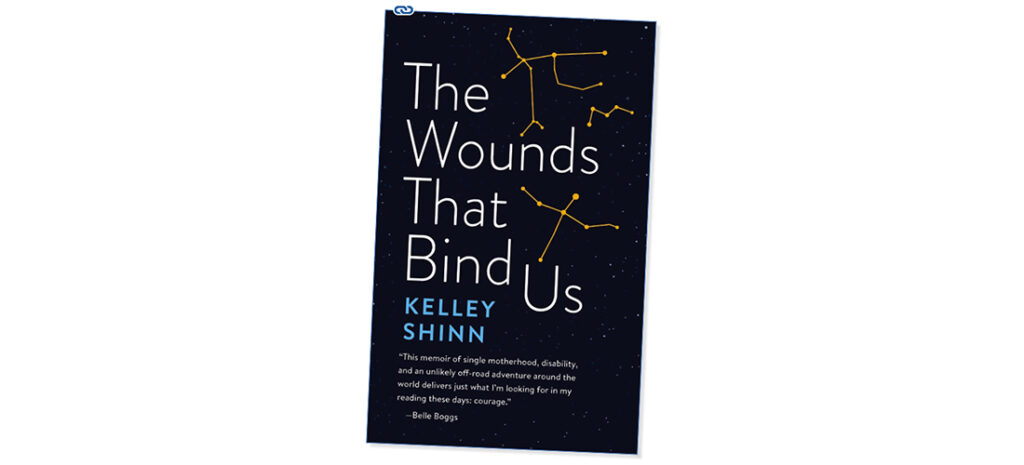

Kelley Shinn spent a long afternoon in a bar with poet Eric Trethewey some years back and told him a story that made him grab her by the shoulders and implore her to write it down.

Shinn had recently returned to the United States from a years-long trip abroad, a nomadic journey she organized to bring attention to the predicament of landmine survivors. As noble an undertaking as that might be, it was not the typical goodwill mission highlighting the plight of amputees whose limbs were blown off in war-torn lands.

A single mother at the time, Shinn — who has prosthetic legs below her knees — was still recovering from her own physical and emotional wounds when she embarked on her global expedition in a tricked-out Land Rover with her whip-smart 3-year-old, Celie. The Wounds That Bind Us, her story chronicling that journey, went through many renditions before becoming the memoir published this year by West Virginia University Press.

Shinn tried a series of short stories first. Next she rewrote it as a novel. “Then I had an agent from New York that was interested in it,” Shinn, now an Ocracoke resident, recounted at a reading at Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill. “And she said, ‘You say it’s based on autobiography. Give me a percentage.’ So I wrote her back and said at this point, it’s 75 percent true. She goes, ‘Here’s my problem. It’s too unbelievable for fiction. You need to rewrite it as memoir.’”

The narrative that came together over the next decade is a phenomenal adventure story that will pull you to the edge of your seat while marveling at Shinn’s candor, steely backbone, vulnerability and wisdom. She takes readers on this emotional ride with self-deprecating humor, artistic prose and a welcome hopefulness that oozes throughout the pages. There are times you want to sit her down, stop her from doing what she’s about to do and tell her the danger’s not worth it — think climbing onto wreckage of a bombed-out bridge in Bosnia high above the Neretva River to get the perfect photo. After all, there’s Celie to think about, the child she brought into the world after 52 hours of labor. Her daughter is her sidekick, a worldly little girl who loves her “to the moon and back.” Who will respond “I love you the whole universe” if Shinn succumbs to unnecessary risks?

Overwhelmingly, readers are more likely to be cheering for Shinn, engrossed in a story that keeps them hungering for the next escapade while also hoping that any one of the many interesting people she encounters along the way can keep her in check.

Shinn was a promising cross-country runner at 16 years old, when her body and life were forever changed by a rare form of bacterial meningitis initially misdiagnosed as flu. Although that’s not how she starts the memoir, she flashes back to that time in the hospital while thinking about landmine victims in Bosnia.

“I’ve got more wires running around and through me than an early desktop computer,” Shinn writes. “A month ago my coach was talking to me about scholarships for cross-country. Lord in heaven, how I wish I could jump off this bed right now and run, just run through the Metroparks, down the city sidewalks, run until my heart pounds in my chest, until the sweat breaks out all over my body and evaporates into thin air.”

There is a sense throughout The Wounds That Bind Us that Shinn is running. Running, running and running. She’s racing away from the pains and sorrows of her childhood and abusive relationships while, at the same time, jogging slowly toward healing and enlightenment. Shinn scratches at deep wounds from being put up for adoption by her birth mother and raised by an adoptive mother who beat her “in a quick rage, with a stick, a belt or a hand.” She explores the mindset that pushed her toward doomed romantic relationships like the one with a scheming first husband who glommed onto her after the well-publicized settlement of her malpractice lawsuit.

This is not a woe-is-me tell-all, though.

Shinn describes unforgettable scenes such as the overnight stay in a brothel with Celie; the off-road thrill rides on steep, rocky terrains; and the beautiful landscapes of Greece. Her stories are filled with memorable characters, from cab drivers to their neighbors in the United Kingdom; from her Greek classics professor turned travel companion to the soldiers, farmers and others with bodies forever altered by landmines; from the many people who care for Celie; all the way to Athena, the Land Rover (a trusted character itself) that does the transporting from England to Serbia, Bosnia and Greece.

It is well worth it to take the journey with Shinn, “that’s two Ns and no shins,” she jokes. She’s funny, daredevilish but relatable. That poet at the bar, a man she would have a relationship and son with, was right. Shinn’s story needed to be written. OH

Anne Blythe has been a reporter in North Carolina for more than three decades covering city halls, higher education, the courts, crime, hurricanes, ice storms, droughts, floods, college sports, health care and many wonderful characters who make this state such an interesting place.

Art of the State

Art of the State

Tag Archives: 2023

Earthen Vessels

From Seagrove to the world beyond, Ben Owen III shares his pottery

By Liza Roberts

The work of Ben Owen III is earthen and practical, but also brightly hued and sculptural. It fits in a hand for morning coffee, but it’s also the lofty centerpiece of elegant spaces across the world. From the Sun Valley Resort in Idaho to the Ritz-Carlton in Tokyo to The Umstead Hotel & Spa in Cary, where his sculptural vessels fill spotlit niches and his handmade plates grace every table, Owen’s art provides beauty and function.

Pottery is one of the oldest human inventions, going back to pre-Neolithic times. Earth into clay, clay into pots, pots into fire, vessels out. Also unchanged: all hands on deck to get it done. It takes a team to keep a wood-fired kiln’s flames stoked and blazing 24 hours a day for days on end. Like farmers raising a barn, potters fire a kiln together because they need each other. It’s what they do.

Owen was born to this life, born with Seagrove clay beneath his feet. His father and grandfather, Ben Owen Sr. and Ben Owen Jr., built the foundations for Seagrove’s modern pottery community; before them, as early as the late 1700s, their forefathers arrived from England, making and selling clay vessels to early settlers. Owen III works today on the same site his grandfather did.

“He was a great teacher and a great mentor for me,” Owen says, “showing me the fundamentals, building all those skills.” Starting at the age of 9, Owen went out to his grandfather’s studio every day to make pots. During these sessions, his grandfather taught Owen technique and aesthetics as well as principles: how important it was to challenge oneself, to learn from mistakes, to greet change with enthusiasm, to eschew mediocrity. To “never sell his seconds.”

“I’m continually trying to find ways to refine the technique and my process,” Owen says. “How can I make the piece even better than I did last time?”

That commitment has taken his work not only all over the world but has paved the way for its inclusion in museum collections, including the Smithsonian Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Gregg Museum of Art & Design, and in private collections. His work, in its various manifestations, has a timelessness about it, even when glazed in crystalline turquoise or lilypad green.

“I’m always experimenting,” he says. “A lot of people know us for our red glaze, but in recent years, I’ve been making glazes from nature. Recreating things I’ve seen hiking with my son . . . looking at textures, lichen on a stone, moss on a tree. It’s interesting to think, Could I make a glaze that would create that effect?”

Some of Owen’s pieces are finished in electric or gas-fired kilns, others in his wood-fired groundhog kiln. To witness Owen firing this kiln — a gourd-shaped, 30-foot-long structure dug partway down into the earth, hence the name — is to witness a multi-day, group massive effort, only accomplished a few times a year.

One recent morning at his studio in Seagrove, Owen was busy completing a 5-foot-tall, 400-pound, bottle-shaped vessel for the Amanyara resort in Turks & Caicos, one of nine large pieces commissioned by the property. The fire in the kiln had been going for 12 hours, and it would be another 36 before it was done. Owen slid a few slats of wood into a slot in the side of the chamber, turning to laugh at a joke from his friend Stan Simmons, a fellow potter there to help keep the fire going at temperatures reaching 2,350 degrees Fahrenheit. Another potter, Fred Johnston, was also on hand. Both men had pots of their own in the kiln. They waited.

“It’s like a jigsaw puzzle,” he said, gesturing to his kiln, explaining how he fits 400 pots inside. Part of it is tactical: Some glazes do well high up, some pots need to be closer to the fire. Some of it is logistical. “Right now,” Owen says, watching flames shoot out of a blowhole-like chimney pipe, “Right now it’s heating up fast. Right now, there’s more fuel than there is oxygen.”

Potters can’t always predict what will emerge from the fire, what that day’s particular combination of clay and heat, minerals and weather will produce. “Colors, or finishes on pots, are almost like sunsets,” Owen says. “Each day, it’s a little different, and depending on what’s present — just as the clouds, or the temperature, the atmosphere all affect the sunset, our glazes can react the same way. We learn to accept that. We try to control these things to the best of our ability, but we have to remind ourselves that our materials are constantly changing. And sometimes it can be a nice surprise.”

A few steps from this kiln, in the late 1990s, Owen built his own studio, right behind the one where his grandfather taught him. The newer spot is spacious, with separate workstations for different kinds of clay. There are pots in various stages of completion, one already 4 feet tall. When it’s complete, this pot will be glazed an earthy blue, weigh about 250 pounds, and stand in the entry of a home in Greensboro.

“In an era of instant gratification, where people can go to the big box stores or a mall for most of their daily needs, we can offer something different,” Owen says. “Especially when they can meet the maker, learn a little bit more about the process, and what makes a potter tick, and their particular style, and why they use that technique. The work becomes part of the fellowship.”

Owen pictures his blue vessel in place, mentions the conversations he’s had with the collectors who’ve commissioned the piece. He welcomes the chance to work closely with the people who collect his work — some of whom were also collectors of his grandfather’s work — and to get to know them, just as he does with visitors to his region and his studio. The role of ambassador is another he embraces.

“When you can find a way to develop a relationship with an individual customer or just people coming out to visit the area,” he says, “that gives us a springboard to tell people more about what the past has done, and what we’ve been able to build on over the last several generations.”

He’s happy to go farther back, too, 280 or 300 million years or so, back to when the region was covered in the volcanic ash that gave birth to the clay he loves, and he’s happy to bring it back home to now, and to his legacy. “I just count my blessings that we’ve been able to support our family through the making of earthen vessels,” he says. “Really, the end product is how it is received by the people who use it.” OH

This is an excerpt from Art of the State: Celebrating the Art of North Carolina, published by UNC Press.

Pleasures of Life Dept.

Pleasures of Life Dept.

Tag Archives: 2023

ADVERTISE

Tag Archives: 2023

Dim Sum-day at Christmas

A hometown guy tests the hot trend of eating Chinese food on Christmas Day

By David Claude Bailey

Now that our two girls are grown-ups and have homes (and Christmas trees) of their own, we empty nesters almost religiously endeavor to spend Christmas morning any place but home — in Savannah, in Florida, in France, in Spain visiting our older daughter.

And then, last November, Anne said, “Let’s not go anywhere this year. Let’s just stay home.”

And so it came to pass that on Christmas morning we find ourselves with our younger daughter, Alice, and her fellow serious eater, Evan, at arguably Greensboro’s most authentic Chinese restaurant, Hometown Delicious.

My idea was to eat in the company of others not entirely focused on little children giggling with delight around a Christmas tree. A few years ago while eating dim sum in Chinatown with Lori, a New York City friend and cookbook author, I heard all about how crowded Big Apple Chinese restaurants are on Christmas day with dim sum eaters.

Literally translated, dim sum means “close to the heart” and encompasses a wide range of hors d’oeuvres, mostly plump dumplings served in steaming bamboo baskets. Once back home, I did a little research. “Going out for dim sum on Christmas Day started as a New York Jewish tradition, spread across America and then caught on across the world,” says the Financial Times.

Getting back to our family summit in November, I proclaim, “Let’s feast on dim sum Christmas morning with Alice and Evan.” They readily agree, though neither had heard about the hot trend of eating Chinese on Christmas morning. I call several Chinese restaurants around town and find that most plan to be closed. One insists that I make a reservation to guarantee a table, which I don’t want to do without consulting my fellow dim (con)sum’ers. Evan, who doesn’t like crowds any more than I do, agrees with me that we ought to eat early to avoid the rush. I have visions of ordering deep-fried sesame balls stuffed with red bean paste only to have the waitress point to another table and say, “They got the last ones.”

So at 11 a.m. sharp, we’re sitting in the parking lot as the lights come on inside Hometown Delicious, and a waitress opens the door with a big smile and a warm welcome. Soon we’re sipping cups of piping-hot wulong tea, a traditional complement to dim sum. I’m glad we’re with family and not in snowy Canada, where I’d suggested going. Or Beirut, Lebanon, where, decades ago, I spent a cold and edgy Christmas on assignment.

To our delight, we have the restaurant totally to ourselves, and, for the first time in months, we are blissfully surrounded by the complete absence of Christmas music.

The menu, however, is almost dim-sumless. Still, we start our feast with an order of pan-fried dumplings, pillowy and stuffed with a savory combination of cabbage and garlicky pork. They are, in fact, delicious, whether they’re hometown or not. I am already one happy camper.

To us, half of the fun of eating Chinese food is sharing all the various dishes. Alice orders eggplant in red sauce as well as spicy mapo tofu. Evan orders pine nuts with corn. Corn? Anne orders the dry-fried green beans. A meat lover, I retaliate by ordering hearty braised duck with beer in an iron pot and a dish the waitress tells us is a specialty of the chef, fish-flavored shredded pork. Anne raises her eyebrows.

As soon as the shiny, purple chunks of eggplant arrive, literally still sizzling, visions of dim sum dancing like sugar plums disappear from our heads. The plump eggplant dissolves, a cloud on our palates, savory with a sauce that leaves you licking your fork. “Oh, my!” Anne says. Alice glows with satisfaction.

“It is cooked in the style of my hometown of Luoyang,” the chef, Jianjun Li, tells us later. (Luoyang is in east-central China in the Henan province — not to be confused with the Hunan, Hainan or Yunnan provinces.) The fish-flavored pork turns out to be a slightly sweet-and-sour stir fry with shreds of pork, slivers of peppers, bamboo shoots, carrots and the same sort of mushrooms found in hot-and-sour soup. “No fish — flavor of fish from the sauce,” Li says. As it swims into our mouths, Evan and I are ecstatic.

We all love the sweet, creamy-fresh corn, stir-fried and amped up with pan-roasted pine nuts. Origin? “Pine nuts with corn is a traditional dish from northeast China,” Li tells us. The dry-fried green beans are from Szechuan, as is the duck cooked in beer, which is my favorite dish. The spicy mapo tofu is, in fact, appropriately described and from Hunan.

Not from his hometown? “These are from my customers’ hometowns,” Li tells us, “so they feel at home in my restaurant.”

Which is where, on this sunny morning, we all feel perfectly at home — in Hometown Delicious.

No need to go to Canada or Florida, we decide over a last cup of tea. Home is wherever your family gathers and eats food cooked by someone who knows how to make people feel happy and at home. It also helps that most of Li’s employees are family members.

As we’re leaving, our waitress says, “Merry Christmas.”

I’ve heard this dozens of times in previous weeks, but not with such total sincerity.

“Merry Christmas to you and all of yours,” I reply.

As we’re stretching our legs and saying our goodbyes outside, I give my daughter a holiday hug and whisper in her ear, “Next year in New York City?” OH

O.Henry’s contributing editor David Claude Bailey fell in love with Chinese cooking 55 years ago when a UNCG faculty member’s wife gifted a wok and a Chinese cookbook to him and his own wife, Anne.