Wandering Billy

Wandering Billy

A Storied Life

Peeking into the pages of 90-year-old Gerald Smith, self-proclaimed Cotton Mill Hillbilly

By Billy Ingram

“I never thought my cotton gin would change history.” – Eli Whitney

I have a shelf in my library devoted to books about growing up in and around the Gate City. That bookshelf just got a little more crowded with the recent addition of a brand new release, Cotton Mill Hillbilly, written by 90-year-old, first-time author Gerald A. Smith, a project he entered into reluctantly.

“My daughters were after me for about six months before I said I would do it,” Smith confesses. “They said, ‘We don’t know anything about your early life.’ They suggested very strongly that, if I valued my life and I wanted to keep eating, I should start writing.” It took him less than six months to complete 302 breezy pages. Raised in Siler City in the 1930s, population 1,775, not counting the livestock, Smith was “surprised it all came back to me once I started.”

Ever hear someone say, “We grew up poor but we didn’t know it?” Not in this telling. “My daddy was a drunk. You couldn’t depend on him for anything,” Smith explains. “We were really poor. We didn’t even have water in the house.” Well, that wasn’t entirely true during inclement weather. “When it rained we had buckets all over the floor. If you got up during the night you had to watch that you didn’t step in the buckets.”

As a youngster, his family had no means of transportation. So, one Saturday his older brother and father ventured out with $125 to buy an automobile. “And they came back on a Czechoslovakian made motorcycle,” Smith says. “That started my career on motorcycles.” Over his lifetime, “I’d have one right after the other and just keep upgrading,” eventually ending up with a top-of-the-line Triumph.

Siler City was the only world Gerald Smith knew as a young’un. “Greensboro was like going overseas, it was so far away,” he recalls. “My dream was to work at Hadley-Peoples, one of the biggest employers in town. I grew up in their mill houses for the first 16 years of my life.” In high school he took a mechanics position for Hadley-Peoples’ petticoat factory, where, some years later, he would meet his future wife, Esta. “It got so hot inside and they had no air conditioning. You could see the lint flying out the windows.” The labor was grueling, the benefits miniscule. “But you had to work somewhere,” says Smith, who earned around $40 a week at the mill. “My brother was at Western Electric in Greensboro and he was making $20 a week more than I was.”

At his sibling’s suggestion, in 1960, Smith went to work at Western Electric in the Pomona district, where “they manufactured top secret, future products. I remember a machine called a Hysteresis Loop. You put a piece of metal on the machine, it gives you a loop and you record the loop.” A couple of years later, an ad in the Greensboro Daily News for “technical minded people” at IBM caught his eye. After interviewing 125 people for one single position, IBM management told Smith they needed to meet his wife before committing.

“Esta was a housewife at the time. She’s beautiful and she knows all the etiquette and everything,” Smith recalls. “She was waiting at the door, greeted them, served refreshments and joined in the conversation. After an hour they got up and said, ‘We’ll make up our decision and let you know.’” As the two recruiters began exiting they stopped and enquired, ‘You still want the job, Gerald?’ I said, ‘More than ever.’ They said, ‘Well, you’re hired.’ They told me later they hired me because of Esta.” Settling in Greensboro — hard times a vanishing point in his motorbike’s rearview mirror — this country boy joined the ranks of the button-down corporate world. “I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t have any suits. I had to go in debt,” Smith says of his Mad Men-era uniform. Wherever he went, ranging out as far as Danville, Virginia, to repair IBM office products, “I had on my suit, crisp white shirt, the shoes had to be shined and you better look good.” Equipped with a proprietary set of tools tucked into a briefcase, employees at his destinations often mistook him for an executive or a doctor, so they routinely waved him through. “I’d go out to Cone Hospital and get right into the area where they kept the radium and isotopes and see all this stuff around and wonder whether this is gonna kill me or not.”

IBM instituted a robust suggestion program with a bonus of up to $50,000 for any employee who submitted a cost-cutting idea that was adopted by the company. “A lot of times we’d be running short of money and they’d present me with a suggestion award.” Smith won 21 of these bonuses before being promoted to field and distribution services manager, allowing him to retire in 1990 and devote more time to church activities.

Looking back, he wonders if maybe he had a bit too much time on his hands, like the time he discovered a baby bird lying on the ground after a windstorm. “This little bitty thing, he just cracked open the egg when he fell and the mother wasn’t there,” Smith says. “Different people said, ‘Feed him some egg yolk.’” Using an eyedropper, “I raised him from the egg to a bird old enough to fly.” He named the bird Nod (bonus points if you get the Andy Griffith Show reference, Wink, Wink). While strolling the neighborhood, Smith tied a string on one of the birdie’s legs and attached it to his baseball cap, using that hat’s bill as a launching pad in an effort to teach the fledgling to fly.

His walks with Nod got the neighbors talking, so much so that Channel 2 dispatched Arlo Lassen to document this Birdman of Hamilton Forest for the 6 p.m. news. Before Nod flew the coop for good, he made a final electrifying appearance: “One morning a telephone guy was coming out to do some work on the lines.” Smith was on the front porch waving to the repairman when Nod flew off a wire, landing on top of his head. “That repairman said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like that before!’”

In so short a space, there’s no way to do justice to the mischief and mayhem contained in this madcap memoir. I recommend you dive into Cotton Mill Hillbilly yourself, available where books are sold and on Amazon. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if some savvy producer turns Smith’s story into a movie.

After 90 revolutions around the sun, despite his soulmate, Esta, passing away in 2010, Gerald Smith isn’t slowing down that much. “I got my driver’s license renewed a few weeks ago,” he tells me. “I thought maybe I’d have trouble taking the eye test. I really can’t see that good, so I spent a couple days memorizing eye charts.” Sure enough he passed and was even grandfathered in for a motorcycle license. He quips, “I might buy me a new Harley or something.” He’s joking, of course . . . at least I think he is. OH

Billy Ingram’s new book about Greensboro, EYE on GSO, is available wherever books are sold or pulped.

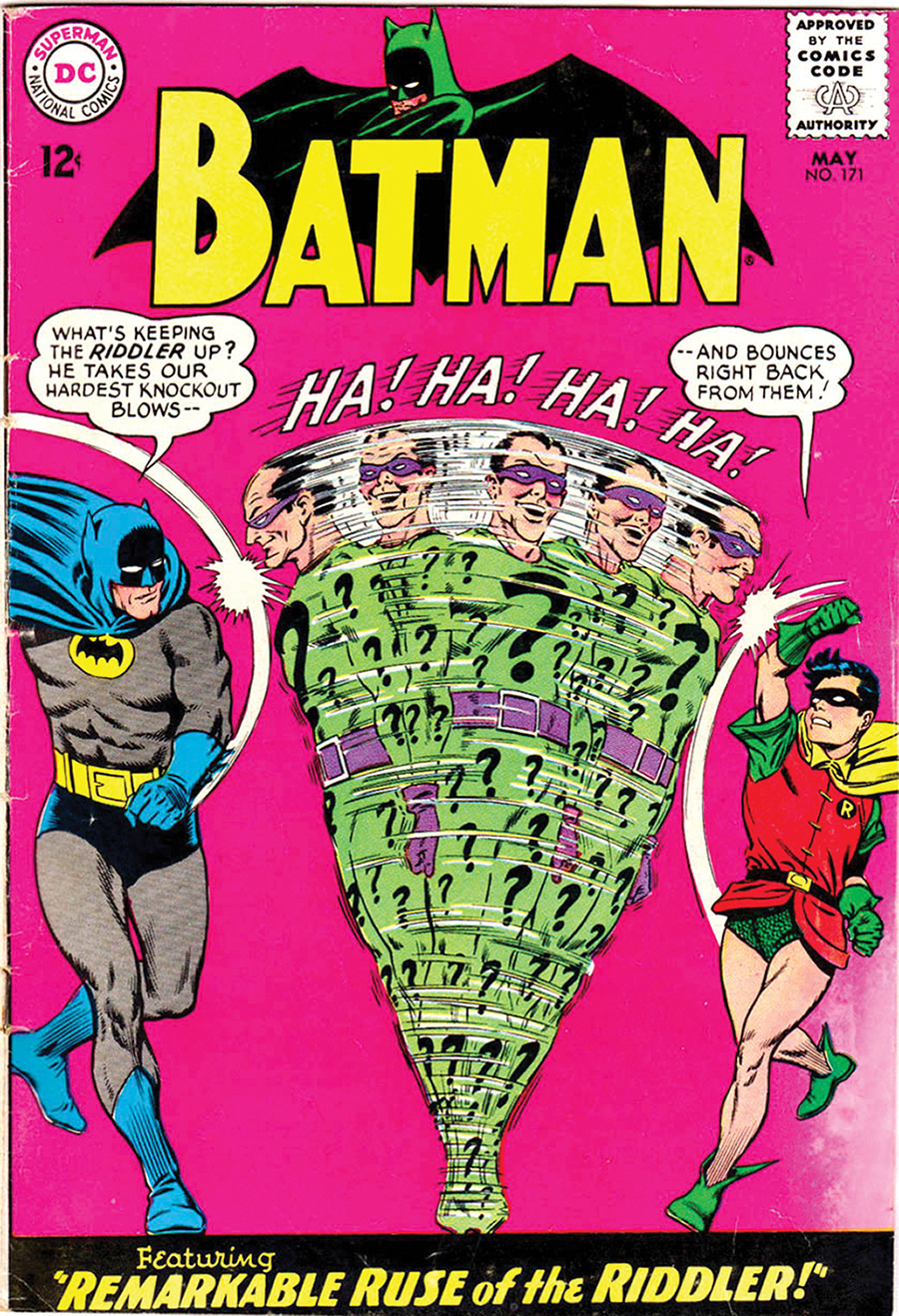

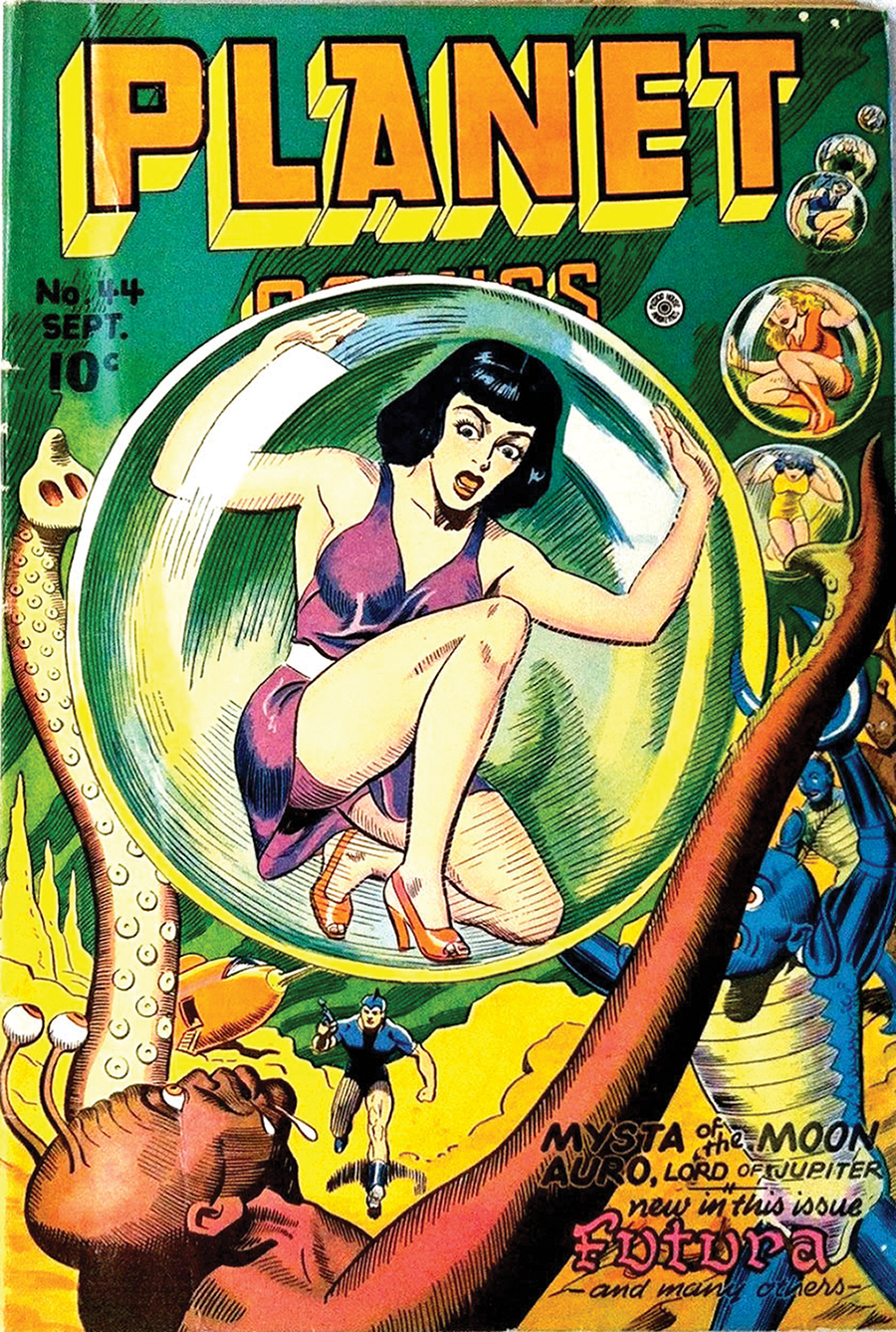

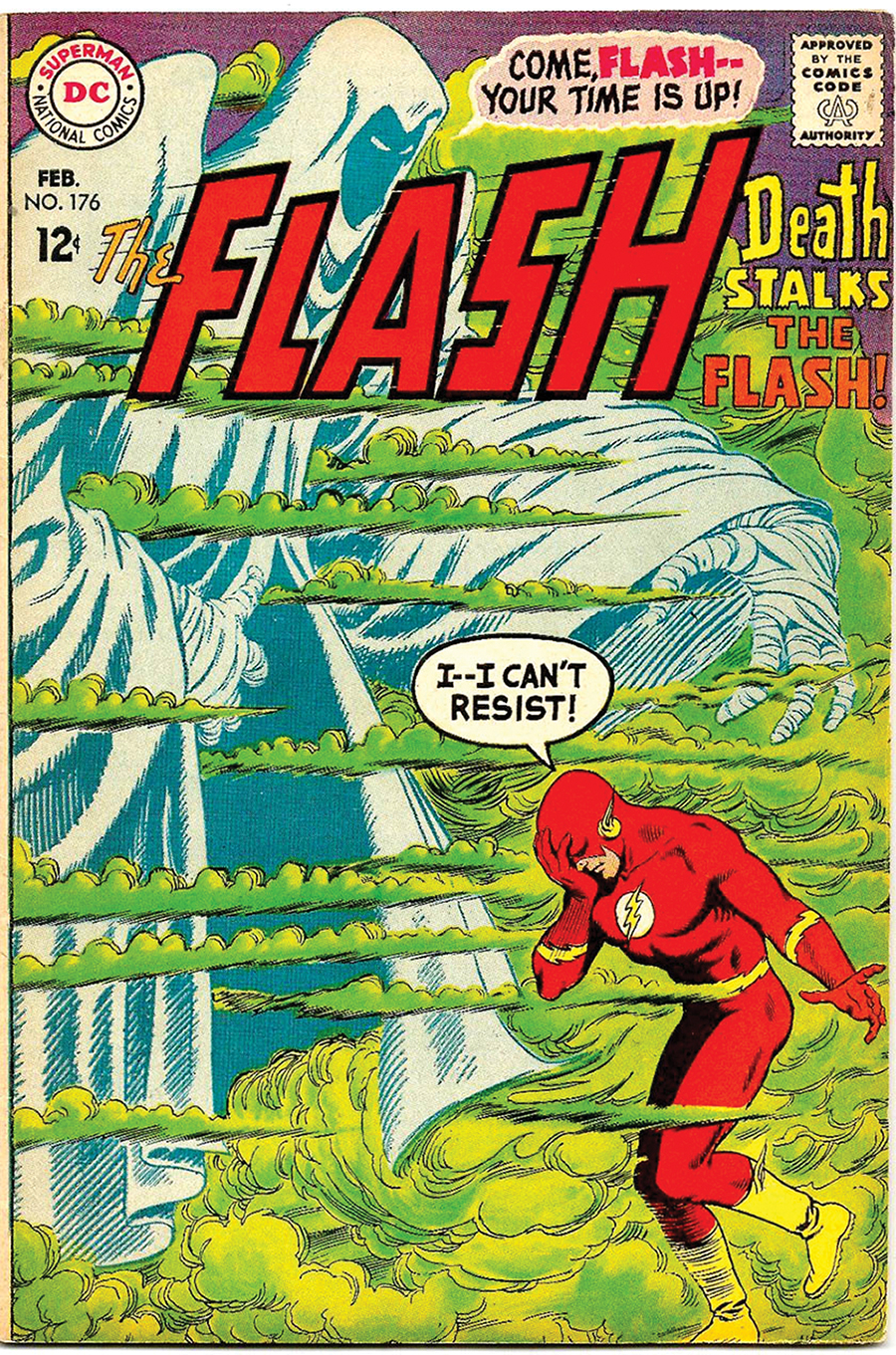

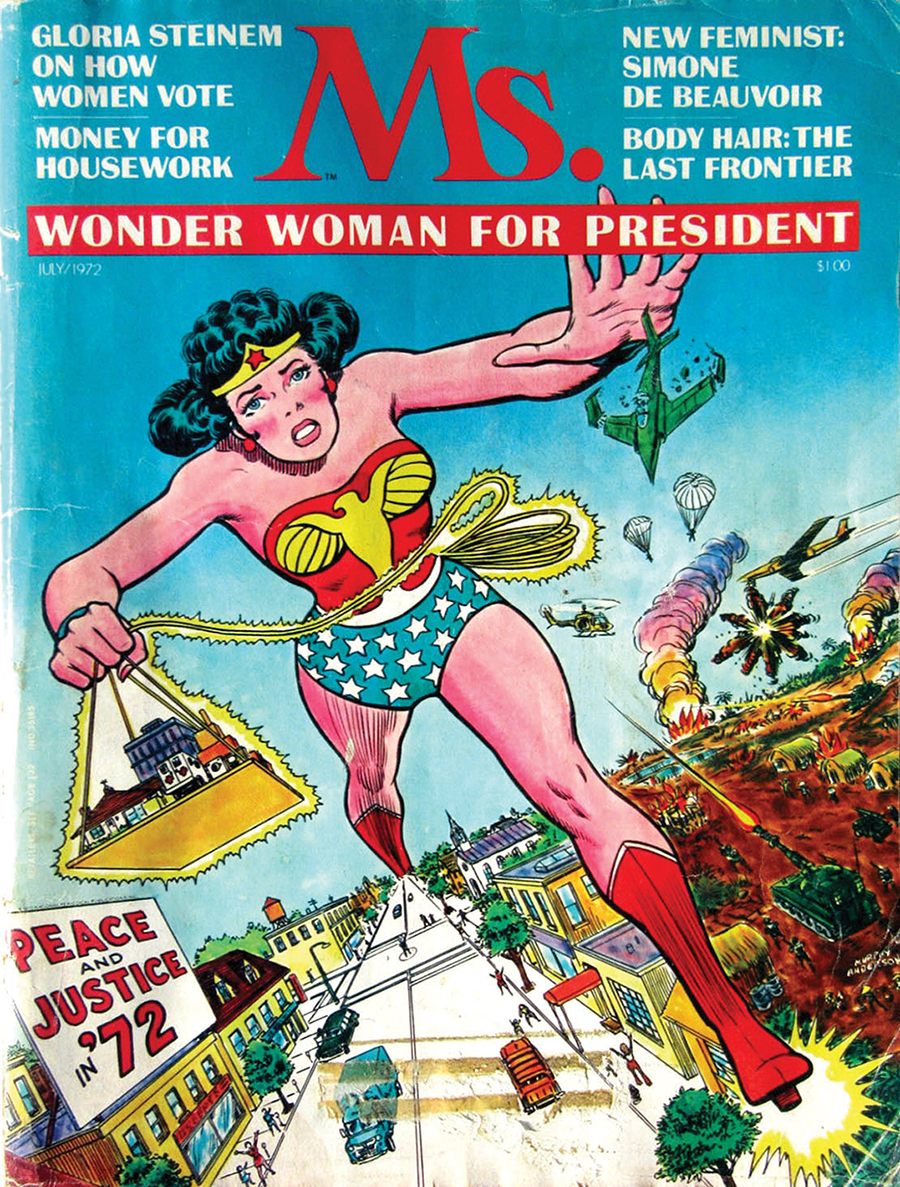

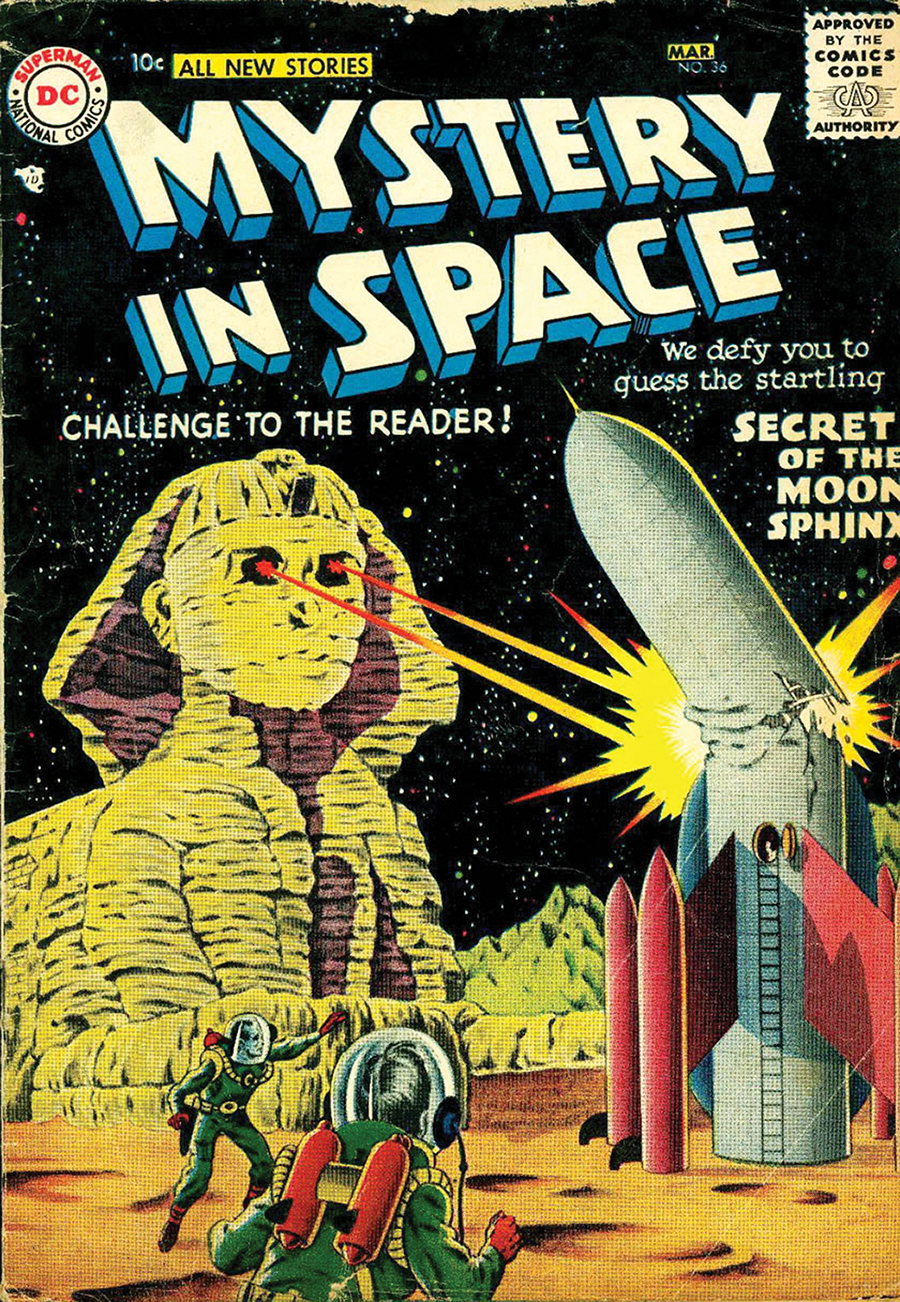

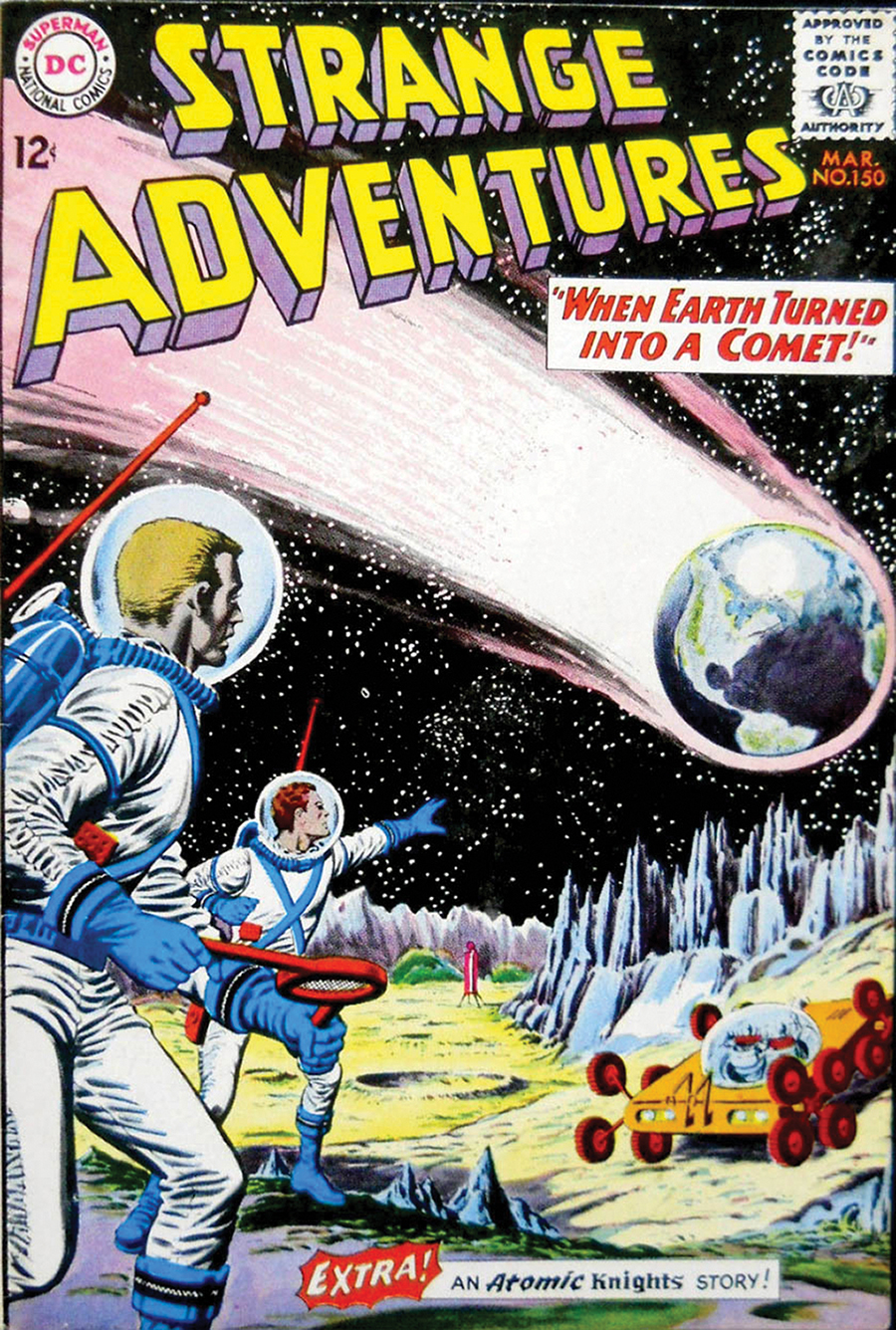

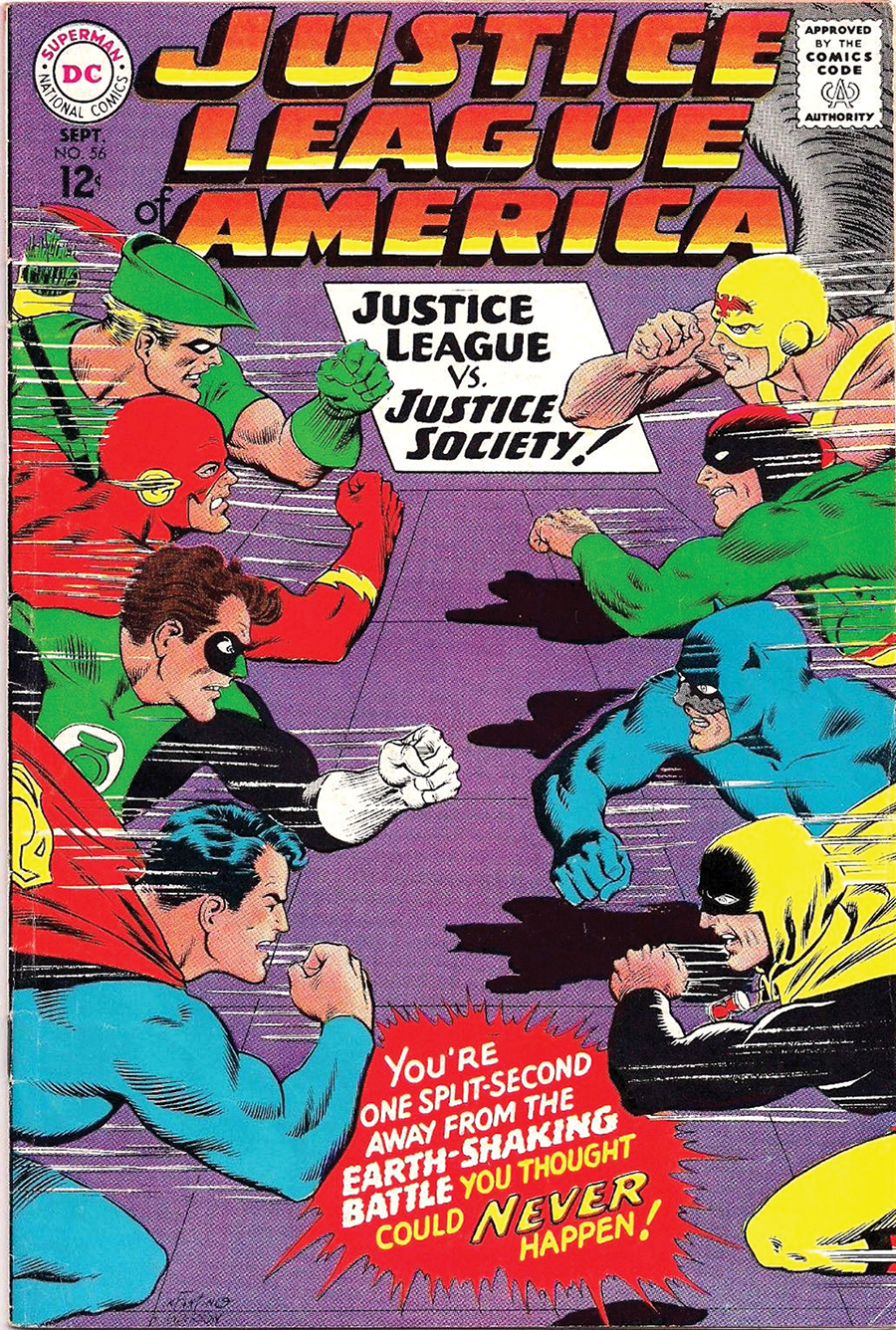

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fav

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fav

A gift you do want this season (no joke): As I write this, local singer-songwriter Caleb Caudle is No. 1 on the Alternative Country Specialty Music chart with his album, Forsythia, that he describes as “somewhere where gospel, folk, country, blues, all that stuff lives together.” Rolling Stone raves about Forsythia saying, “There’s something very comforting about listening to it, but not in a cheap or obvious way. It’s more hard-won.” It’s an exquisitely produced album that resonates. I didn’t grow up listening to music like this, yet Caudle’s melodies sound like home. Available on the usual music platforms such as Spotify and Amazon.

A gift you do want this season (no joke): As I write this, local singer-songwriter Caleb Caudle is No. 1 on the Alternative Country Specialty Music chart with his album, Forsythia, that he describes as “somewhere where gospel, folk, country, blues, all that stuff lives together.” Rolling Stone raves about Forsythia saying, “There’s something very comforting about listening to it, but not in a cheap or obvious way. It’s more hard-won.” It’s an exquisitely produced album that resonates. I didn’t grow up listening to music like this, yet Caudle’s melodies sound like home. Available on the usual music platforms such as Spotify and Amazon.