How the Jacksons ended up with two old homes — and contentment

By Ross Howell Jr.

Photographs by Amy Freeman

On a summer evening, I’m sitting with my neighbors, Jane and Randy Jackson, in the living room of their house overlooking Fisher Park.

Shaded by big oaks and a magnolia, it’s a graceful old home that I’ve admired ever since I moved into the neighborhood 13 years ago.

Jane grew up in Winston-Salem, graduated from Reynolds High School and went off to Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia. Randy grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, moving with his family to Atlanta when he was in 10th grade.

“Football was my life in high school,” Randy says. So when the University of Alabama phoned him in Georgia, asking him to try out as a walk-on, he gave up his plan to study marine biology at the University of Florida.

After going through two-a-day practices, an injury and doubts about his ability to play at such a high level, Randy decided to give up football. He finished his freshman year at Alabama and transferred to Georgia Tech.

“My Dad was between jobs,” Randy explains, “and paying out-of-state tuition, so I decided to come back to Georgia to help with finances.”

It was a good move.

In Atlanta, Randy met Jane on a blind date. They were married during her senior year at Agnes Scott.

The next year, Randy entered his first year of study at the Medical College of Georgia.

“She went through medical school with me,” Randy says.

“In a house with no air conditioning in Augusta, Georgia,” Jane adds. “And pregnant.”

“She’s a tough, tough girl,” Randy says, beaming at his wife.

Later, the couple moved to Jane’s hometown of Winston-Salem for Randy’s internship and residency at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, then on to Greensboro for private practice in 1982.

“We loved Fisher Park,” Jane says, “but, back then, younger kids were picked up early and bussed a long way to school.” The Jacksons didn’t want their 5-year-old daughter, Alice, and 8-year-old son, Freeman, spending so much time aboard a bus.

So they settled into a small house on Elmwood Drive in Irving Park.

“There were 28 kids on that street who were between my two children’s ages,” Jane says.

“I would come home from the hospital and be attacked by these little kids,” Randy laughs. “I’m not talking about one or two. I’m talking about a whole herd of them!”

“And we had Page High School kids, too,” Jane adds.

Remembering how important sports had been to him as a youth, Randy decided to spring for a “sport court” in the backyard of their house.

“And there we were,” Jane says, “inundated with all this medical school debt.”

Randy’s facility had a basketball hoop and tennis nets. Children played there constantly, and neighborhood dads enjoyed pickup basketball games, too.

“It was like a community center,” Jane recalls. “We used to call it Jackson Park.” They smile, reflecting on the memories.

“So we lived there for a while and then we moved to another house a little bit bigger a couple blocks away,” Randy says. “Then our kids finished high school . . .”

“And went off to college,” Jane finishes.

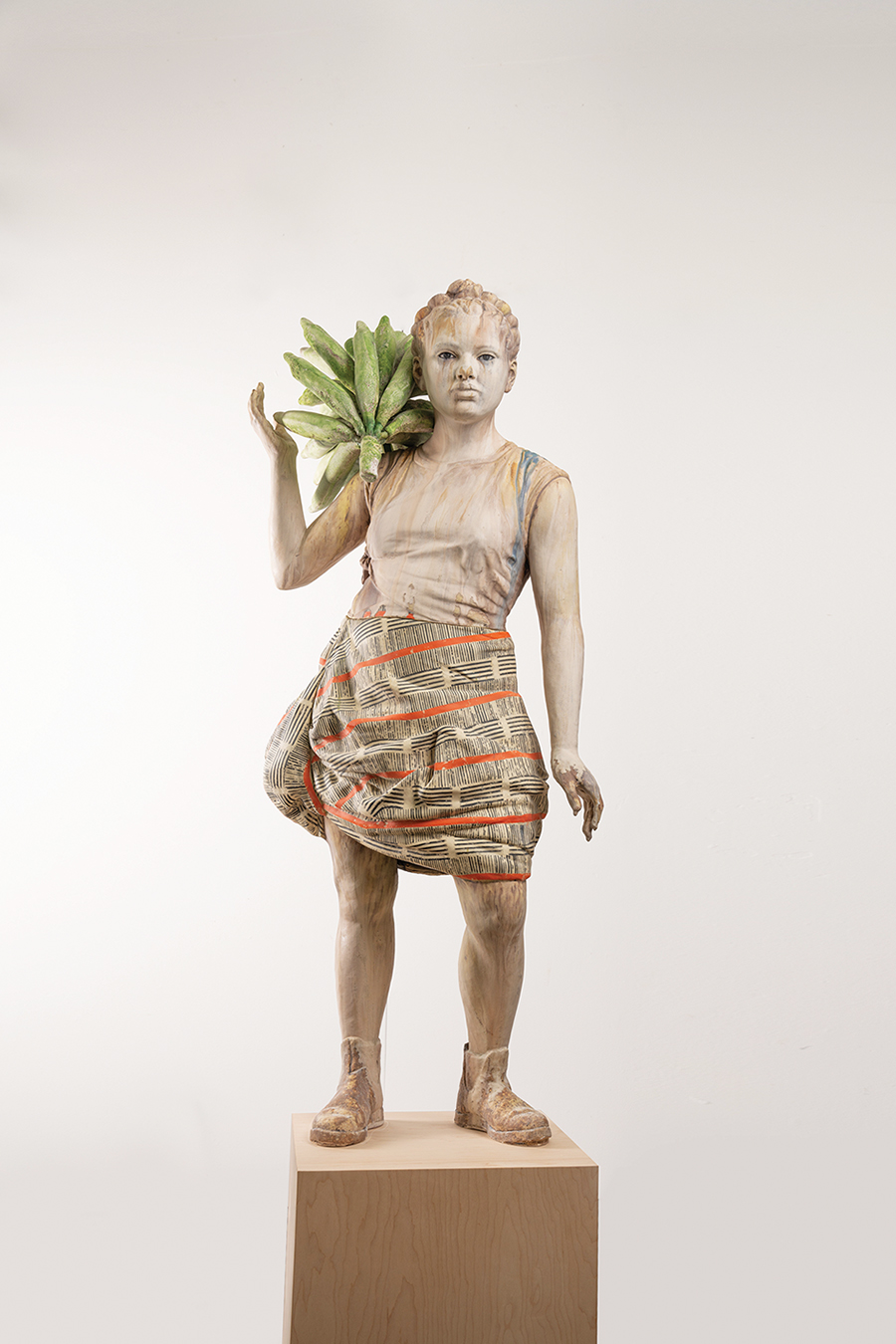

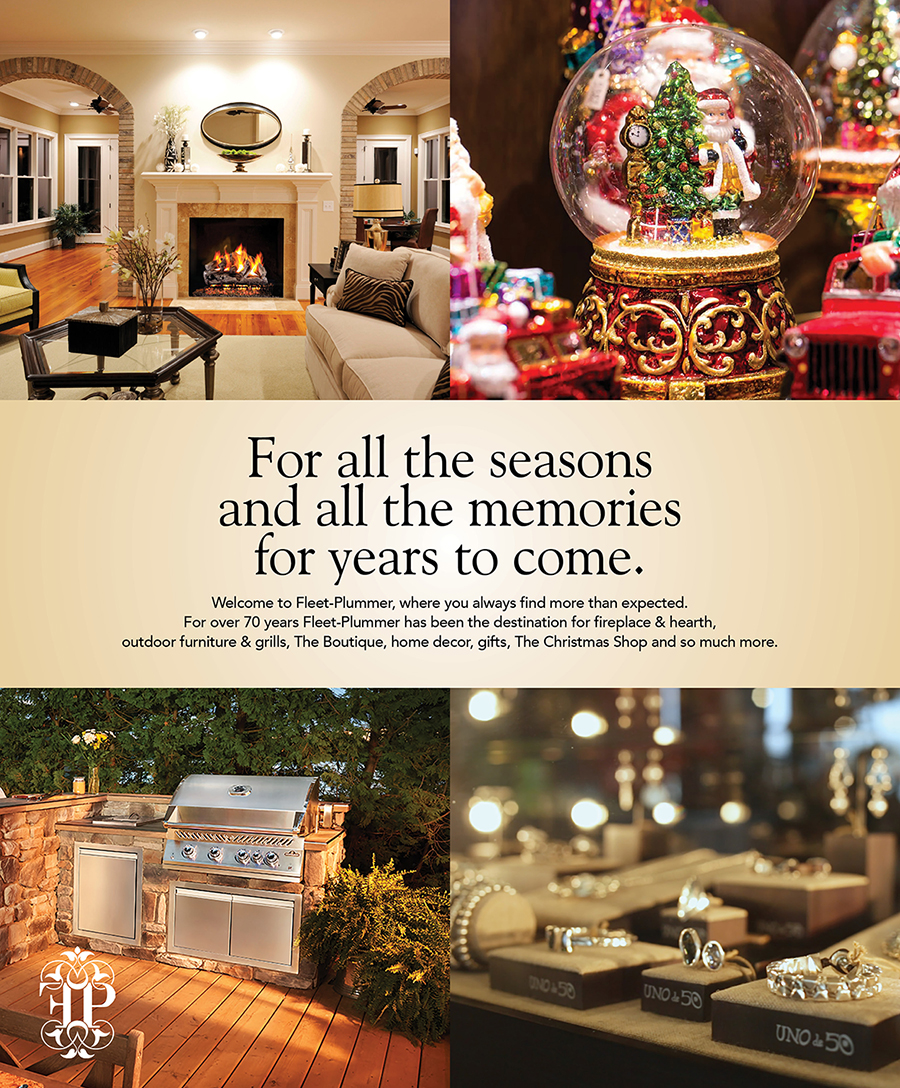

With Freeman and Alice out of the nest, you may think we’ve come to the point in the story where the Jacksons will purchase the graceful, cedar-sided Fisher Park house where we’re sitting, with its metal-picketed fence draped with ivy and thick-columned front porch festooned with wisteria.

Nowhere near it.

Not long after the Jacksons had moved into their first little house on Elmwood, they purchased property in Summerfield.

“Randy had always wanted a farm,” Jane explains.

“We had nothing on it,” Randy says. “Just land and a pond.”

One evening, while the Jacksons were attending a pop-up supper at a home in Irving Park, they noticed a picture of a log cabin hanging over the fireplace. Seeing their interest, one of the guests commented, “There’s a cabin like that up in Virginia near Smith Mountain Lake.”

“Maybe you’d like something like that on your farm,” he added.

To which Jane replied, “I’d love that.”

The price for the log cabin was reasonable, but it would have to be dismantled and moved to the Jacksons’ property.

“So I thought, maybe I could put it up!” Randy laughs. “I’m strong, I used to play football!”

After the cabin in Virginia had been thoroughly photographed and the logs meticulously numbered, it was Jane who followed the truck transporting them to Summerfield.

“Those logs aren’t what you see in tobacco barns,” Jane says. “They’re 16-inch oak and chestnut.”

Thinking she’d like the cabin situated with a view of the pond, she guided the truck to that corner of the property to unload.

“They dumped them like a huge pile of pickup sticks!” Randy exclaims. “And each one of those pickup sticks weighed 300 or 400 pounds.”

Then Jane reconsidered. It was humid near the pond, she reflected, plus they didn’t own the land beyond, so there was no telling how the view might change in the future.

“I don’t feel good about this,” she said to Randy. The logs would have to be moved to another location.

“All I had was a Ford Bronco,” Randy says.

“So I bought an old tractor, a John Deere 1010,” Randy says. “I had a boom and chain I’d hook up to the three-point hitch on the back of the tractor, and I’d put the chain around a log, pick it up and drag it to the new location.” He placed the logs atop rocks to help prevent rot and arranged them by number.

“Sort of like the walls had fallen over,” Randy says. “It took forever.”

“We didn’t know what we were doing,” Jane adds.

They recruited their children on weekends to remove nails and pieces of tarpaper siding that had once covered the logs.

“The kids thought it was like prison camp,” Jane chuckles. “They’d call all their friends, trying to get them to come help.”

Eventually the Jacksons built a shelter to keep the old logs out of the rain. That was the first structure on the property.

Randy asks Jane if she remembers how long the process took.

“Six years,” Jane answers, and pauses. “You know, they built the Biltmore in six years.”

She’s right —1889 to 1895 — and we share a big laugh.

Finally, the time came when the Jacksons were ready to have a foundation built and begin erecting the logs. After much research and reading, Randy decided that the task might be more than he and his antique tractor could undertake.

While driving out U.S. Highway 220 at Guilford Courthouse National Battleground Park, he’d noticed that a log barn and log house were being restored. One day when he saw men working, he decided to stop and speak with them.

There he introduced himself to the man who seemed to be supervising the work, Si Rothrock.

“I know where there’s a log house on the ground that has logs bigger and fatter than those logs,” Randy said to Rothrock. “Furthermore, the logs don’t have cathedral notches or half-dovetails, they have full dovetails.”

“You know where there’s a house like that?” Rothrock asked.

“Oh, yeah,” Randy said. “It’s only a few miles from here.”

Turns out, Rothrock was one of the owners of Reidsville Building Supply Co., a business founded in 1920 by Rothrock’s grandfather. Over the years, Rothrock had become an expert at restoring old log houses.

“He’s like a genius,” Randy says. “He could write books.”

Rothrock agreed to ride out to Summerfield with Randy to have a look. When they arrived, he began to examine the logs closely.

“This is a very rare thing you’ve got here,” Randy recalls Rothrock saying.

He told Randy because of the large size of the logs and the fact that they were fashioned with full dovetail corners, the cabin likely was built by German workmen sometime before the Revolutionary War.

“Something like this shouldn’t be wasted,” Rothrock said. “Maybe somebody who knows something about it should put this up.”

Randy agreed.

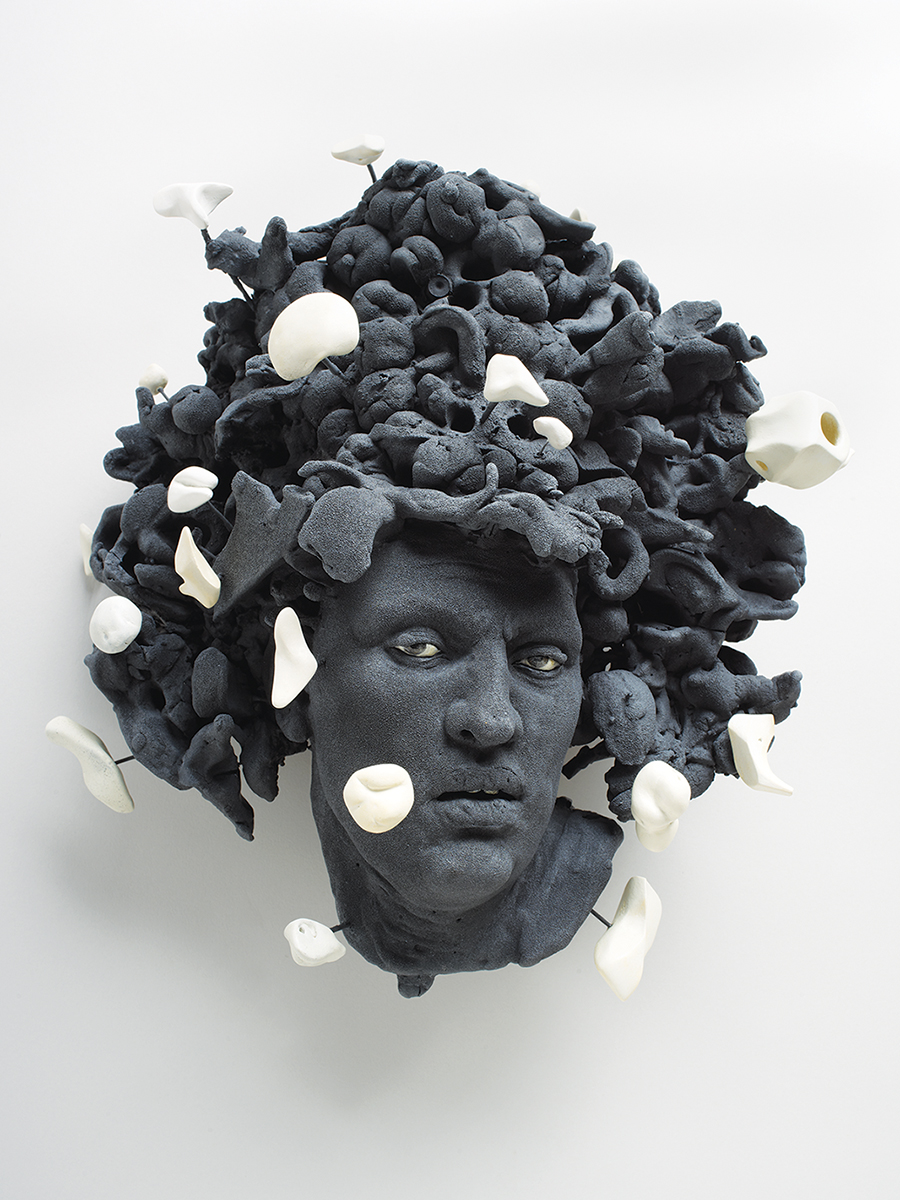

The Jacksons tell me how they marveled at the craftsmanship of Rothrock’s subcontractors. They were rough-and-tumble country boys, but they were true artists in stone and wood.

“I loved watching the stone mason,” Jane says. “You wouldn’t believe how big those boulders he worked with were. He was unbelievable.”

“His name was Frank Norton,” Randy says. “He had the best eye.” Randy tells me how the cabin foundation looks like dry stack stone from the outside, but, in fact, is held by mortar on the inside.

Even with experienced, knowledgeable workmen, “it was a long, drawn-out process,” Randy says.

Some of the original logs were in such poor condition that replacements had to be made. Randy took this handiwork on himself, cutting trees on the property and shaping them using a broadaxe, just as German workmen would’ve done back in the day.

Cleaning the old logs, and fashioning and curing new ones continued. Sometimes they were hoisted by crane into position, only to be lowered back down because the dovetails didn’t fit properly and had to be redone.

Jane recalls a plumber having trouble getting the right size elbow to install under the house. He came inside and asked to use the phone, not realizing that she could hear his conversation from the kitchen.

Jane remembers him saying to his buddy on the phone, “You won’t believe this place, it’s like The Beverly Hillbillies.”

There was a pause, and then he said, “No, before they got the crude.” Again, we enjoy a good laugh.

And the Jacksons continued to pitch in with the work. Jane installed the molding for the kitchen windows and trimmed the pantry. Randy concentrated on the never-ending task of chinking logs. They both sanded the floors by hand — some of them wood from the original cabin, some reclaimed lumber from an old schoolhouse.

“There’s absolutely nothing about this place that is anything but unusual,” Randy says.

The cabin had one bathroom. Up a stairway from the living room was a bedroom they called “the barracks,” which featured five single beds where they could pack in children coming home from college with their friends. And there was a snug little bedroom under the roofline of the kitchen. The Jacksons built a shed onto the cabin that begat another, including a large, bright sunroom.

“The house is like a chambered nautilus,” says Jane. “One thing after another.”

With the cabin now habitable and the children no longer at home, the Jacksons sold their Irving Park house and moved to Summerfield, where they remained full-time for 12 years. Daughter Alice was married at the farm. When grandchildren came along, they celebrated birthdays there and played in the pastures and woods.

“Why would you want to live anywhere else?” visiting friends would often ask the Jacksons.

Which brings us to the city house.

“Randy’s still practicing medicine then, and there’s a hospital merger,” Jane recalls.

That meant that he was on call to hospitals in Reidsville, Randleman, Siler City, Lake Norman, Statesville and elsewhere.

“Sometimes I’d be driving home after being up all night and fall asleep in the car,” Randy adds.

The Jacksons decided they needed a place in Greensboro, which is more centrally located. They were looking for a small townhome or even an apartment.

But when a tennis buddy told Randy about a home in Fisher Park on the market, the Jacksons decided to have a look in the neighborhood that had first attracted them.

“The way the house smelled, the way it looked, reminded me so much of my Grandma’s house,” Randy says. “She was the neatest lady.”

Though they knew they didn’t need the space, Randy and Jane decided they had to have this lovely old place.

“It’s an illness,” Jane laughs.

The house had once been on the Greensboro Symphony Guild’s Tour of Homes, and a News & Record article described the big front porch as its most impressive feature. The house was designed by Greensboro architect Raleigh James Hughes in the colonial revival style and was built about 1915 for F. P. Hobgood, a local attorney.

“A subsequent owner, Cadillac dealer E. B. Adamson, made considerable changes to the house in 1949,” the N&R article continues. Adamson oversaw the creation of “a 9-foot-wide hall that runs through the house and opens onto a backyard garden.”

“With its 10-foot ceiling, hardwood floor and spacious feel, the hall is the home’s second most dramatic feature,” the article concludes.

Most any visitor would agree.

While the Jacksons made improvements when they purchased the house in 2004, they’ve just recently finished another renovation, converting a sleeping porch, small bathroom and what had been a study for a previous owner, retired Guilford College professor Bill Carroll, into a large master bedroom on the first floor — as had been specified in the architect’s original drawings — along with a spacious bathroom.

The Jacksons give me a tour. Jane points out the many windows and tells me how light floods the rooms, especially in the morning. They show me the new powder room for party guests, and where the Christmas tree gets placed in the hall for the holidays.

“We’ve been in this house as long as any house we’ve been in, other than the farm,” Randy says, as I’m preparing to leave. “We love this place.”

“We goofed with the grandchildren, though,” Jane says.

There are six grandkids in all — three in Charlotte and three in Wilmington.

Randy explains that he’s asked the older grandchildren if he ever needed to sell the farm, would that be a problem? He tells me they solemnly informed him they would get together with their parents and buy the farm.

“With their allowances,” Jane adds, a twinkle in her eye.

“So many memories,” Randy says. “We could never sell the farm.” OH

Ross Howell Jr. is a contributing writer to O.Henry. His historical novel, Forsaken, is available at bookstores and online.